The Buried History of the Winchester Geese: Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Halloween of Cross Bones Festival of 2007, the Role of the Graveyard Gates and the Monthly Vigils That Take Place There

Honouring The Outcast Dead: The Cross Bones Graveyard Presented at the 'Interfaith & Social Change: Engagements from the Margins' conference, Winchester University (September 2010) by Dr Adrian Harris. Abstract This paper explores the emergence of a unique 'sacred site' in south London; the Cross Bones graveyard. Cross Bones is an unconsecrated graveyard dating from medieval times which was primarily used to bury the prostitutes who were excluded from Christian burial. Archaeological excavations in the 1990's removed 148 skeletons and estimated that some 15,000 bodies remain buried there. Soon after the excavations began, John Constable, a London Pagan, began to hear "an unquiet spirit whispering in [his] ear" who inspired him to write a series of poems and plays which were later published as 'The Southwark Mysteries ' (Constable, 1999). 'The Southwark Mysteries' in turn inspired the first Cross Bones Halloween festival in 1998, and the date has been celebrated every year since, to honour "the outcast dead" with candles and songs. Although the biggest celebration is at Halloween, people gather at the gates on the 23rd of every month for a simple ritual to honour the ancestors and the spirit of place. Offerings left at the site are often very personal and include ribbons, flowers, dolls, candles in jars, small toys, pieces of wood, beads and myriad objects made sacred by intent. Although many of those involved identify as Pagans, the site itself is acknowledged as Christian. Most - if not all - of those buried there would have identified as Christians and the only iconography in the graveyard itself is a statue of the Madonna. -

The Library of 'Flesh': a Return to Bodily Perception

The Library of 'flesh': A return to bodily perception Amy Lam, B AS. A thesis submitted to The Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture (Professional) Azrieli School of Architecture and Urbanism Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada Amy Lam © 2009 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-51989-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-51989-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nntemet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Palace-House-Brochure-FINAL-Mar

PALACE HOUSE 3 CATHEDRAL STREET SOUTH BANK SE1 Prime long let freehold investment opportunity Contents INVESTMENT Summary 04 / 05 Location 06 / 13 Connectivity 14 / 15 Local Occupiers 16 / 19 Local DEVELOPMENT pIPELINE 20 / 21 Description 24 / 25 Specification 26 Accommodation 27 Floor Plans 28 / 29 Tenure and TENANCY 30 / 31 Covenant Information 32 Asset Management 33 SOUTH BANK MARKET 34 / 35 Contact & FURTHER INFORMATION 36 / 37 01-02 INVESTMENT SUMMARY Freehold. Located in the thriving South Bank district adjacent to Borough Market. London Bridge station is within a five minute walk from the property. Currently under refurbishment by Kaplan, the property comprises 45,012 sq ft (4,182 sq m) of accommodation arranged over ground and five upper floors. The accommodation includes 43,083 sq ft (4,002 sq m) of office and ancillary accommodation and a retail unit at part-ground and part-first floor extending to 1,929 sq ft (179 sq m). The office space is single let to Kaplan Estates Limited guaranteed by Kaplan UK Limited, a 5A1 rated company, for a term of 15 years expiring 31st August 2032, with a tenant option to determine on 31st August 2027. The overall passing rent of the office accommodation is £2,453,165.50 per annum (£57.76 per sq ft). The retail unit is let to Nero Holdings Limited t/a Caffè Nero for a term of 15 years from 11th June 2007 expiring 10th June 2022. The rent payable is subject to a minimum base rent of £150,000 per annum and an additional turnover rent (if applicable). -

Death, Time and Commerce: Innovation and Conservatism in Styles of Funerary Material Culture in 18Th-19Th Century London

Death, Time and Commerce: innovation and conservatism in styles of funerary material culture in 18th-19th century London Sarah Ann Essex Hoile UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Declaration I, Sarah Ann Essex Hoile confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: Date: 2 Abstract This thesis explores the development of coffin furniture, the inscribed plates and other metal objects used to decorate coffins, in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century London. It analyses this material within funerary and non-funerary contexts, and contrasts and compares its styles, production, use and contemporary significance with those of monuments and mourning jewellery. Over 1200 coffin plates were recorded for this study, dated 1740 to 1853, consisting of assemblages from the vaults of St Marylebone Church and St Bride’s Church and the lead coffin plates from Islington Green burial ground, all sites in central London. The production, trade and consumption of coffin furniture are discussed in Chapter 3. Chapter 4 investigates coffin furniture as a central component of the furnished coffin and examines its role within the performance of the funeral. Multiple aspects of the inscriptions and designs of coffin plates are analysed in Chapter 5 to establish aspects of change and continuity with this material. In Chapter 6 contemporary trends in monuments are assessed, drawing on a sample recorded in churches and a burial ground, and the production and use of this above-ground funerary material culture are considered. -

Winter 2014 Newsletter

Chiltern District Welsh Society Winter Newsletter 2014 Written By Maldwyn Pugh Chairman’s Report London Walk - 26th July 2014 Well, we’ve had a very successful six months. We’ve welcomed yet more new members: we’ve held a diverse range of events, all of which have been well attended and enjoyed. If that sounds familiar it is because: (1) the Society continues to thrive; and (2) it becomes difficult to find new words to describe a thriving Society! A small group of members met our guide Caroline James, at the foot of The Shard on a A pleasant and informative walk around the sunny Saturday in June to explore sites South Bank; yet another enjoyable and sunny around Southwark. golf day; five days based in Swansea during which we saw barely a drop of rain (!); the The area is at the wonderful sound of the massed choirs at the southern end of Albert Hall: and that was just in a few London Bridge which months! in medieval times was closed at night. I don’t have the gift of words possessed by our most recent speaker, the poet Professor Many inns were built Tony Curtis, so I’m going to let the reports there and thrived as themselves do the talking. staging posts for travellers. Theatres We have a lot to look forward to, and I hope opened there as did our 2015 events prove as successful and hospitals for the popular as those of 2014 – not forgetting that poor, sick, incurables, and homeless. Bear we have one of our favourite events of the baiting, prostitution, and similar activities year – the Christmas Drinks party - still to which were come! illegal in the City flourished. -

The Politics of Architecture in Tudor and Stuart London Transcript

The Politics of Architecture in Tudor and Stuart London Transcript Date: Thursday, 11 February 2010 - 12:00AM Location: Museum of London The Politics of Architecture in Tudor and Stuart London Professor Simon Thurley Visiting Gresham Professor of the Built Environment 11/12/2010 Tonight, and again on the 11 March, I will be looking at the interrelation of architecture and power. The power of kings and the power of government and how that power has affected London. On the 11th I will be looking at Victorian and Edwardian London but tonight I'm going to concentrate on the sixteenth and seventeenth century and show how Tudor and Stuart Monarchs used, with varying degrees of success, the great buildings of the City of London to bolster their power. The story of royal buildings in the City starts with the Saxons. Before 1052 English Kings had had a palace in London at Aldermanbury, but principally to avoid the instability, turbulence and violence of the populace Edward the Confessor, the penultimate English King, had moved his royal palace one and a half miles west to an Island called Thorney. On Thorney Island the Confessor built the great royal abbey and palace of Westminster. And it was here, that William the Conqueror chose to be crowned on Christmas day 1066, safely away from the still hostile inhabitants of the city. London was too big, powerful and independent to be much influenced by the Norman Conquest. Business continued unabated under a deal done between the city rulers and their new king. However William left a major legacy by establishing the metropolitan geography of the English monarchy - the subject of my talk this evening. -

BANKSIDE, BOROUGH & LONDON BRIDGE Characterisation STUDY

APPENDIX 8 BANKSIDE, BOROUGH & LONDON BRIDGE CHARACTERISATION STUDY JULY 2013 Bankside, Borough and London Bridge Characterisation Study page 2 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 6 2. StrategiC CONTEXT 10 3. TOWNSCAPE CHARACTER AREAS 22 3.1 BLACKFRIARS ROAD NORTH 23 3.2 BLACKFRIARS ROAD SOUTH 33 Limitations 3.3 BANKSIDE CULTURAL 43 URS Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“URS”) has prepared this Report for the sole use of Southwark Council (“Client”) in accordance with the 3.4 BANKSIDE COMMERCIAL 53 Agreement under which our services were performed [3117681. 19 October 2012]. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by URS. This 3.5 BOROUGH MARKET 61 Report is confidential and may not be disclosed by the Client nor relied upon by any other party without the prior and express written agreement of URS. 3.6 THE BOROUGH 70 The conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report are based upon information provided by others and upon the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has 3.7 BOROUGH HIGH STREET 79 been requested and that such information is accurate. Information obtained by URS has not been independently verified by URS, unless otherwise stated 3.8 LONDON BRIDGE 89 in the Report. The methodology adopted and the sources of information used by URS in 3.9 BERMONDSEY 104 providing its services are outlined in this Report. The work described in this Report was undertaken between [insert date] and [insert date] and is based on the conditions encountered and the information available during the said REFERENCES 115 period of time. -

Redating Pericles: a Re-Examination of Shakespeare’S

REDATING PERICLES: A RE-EXAMINATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S PERICLES AS AN ELIZABETHAN PLAY A THESIS IN Theatre Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by Michelle Elaine Stelting University of Missouri Kansas City December 2015 © 2015 MICHELLE ELAINE STELTING ALL RIGHTS RESERVED REDATING PERICLES: A RE-EXAMINATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S PERICLES AS AN ELIZABETHAN PLAY Michelle Elaine Stelting, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2015 ABSTRACT Pericles's apparent inferiority to Shakespeare’s mature works raises many questions for scholars. Was Shakespeare collaborating with an inferior playwright or playwrights? Did he allow so many corrupt printed versions of his works after 1604 out of indifference? Re-dating Pericles from the Jacobean to the Elizabethan era answers these questions and reveals previously unexamined connections between topical references in Pericles and events and personalities in the court of Elizabeth I: John Dee, Philip Sidney, Edward de Vere, and many others. The tournament impresas, alchemical symbolism of the story, and its lunar and astronomical imagery suggest Pericles was written long before 1608. Finally, Shakespeare’s focus on father-daughter relationships, and the importance of Marina, the daughter, as the heroine of the story, point to Pericles as written for a young girl. This thesis uses topical references, Shakespeare’s anachronisms, Shakespeare’s sources, stylometry and textual analysis, as well as Henslowe’s diary, the Stationers' Register, and other contemporary documentary evidence to determine whether there may have been versions of Pericles circulating before the accepted date of 1608. -

A HISTORY of LONDON in 100 PLACES

A HISTORY of LONDON in 100 PLACES DAVID LONG ONEWORLD A Oneworld Book First published in North America, Great Britain & Austalia by Oneworld Publications 2014 Copyright © David Long 2014 The moral right of David Long to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78074-413-1 ISBN 978-1-78074-414-8 (eBook) Text designed and typeset by Tetragon Publishing Printed and bound by CPI Mackays, Croydon, UK Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR England CONTENTS Introduction xiii Chapter 1: Roman Londinium 1 1. London Wall City of London, EC3 2 2. First-century Wharf City of London, EC3 5 3. Roman Barge City of London, EC4 7 4. Temple of Mithras City of London, EC4 9 5. Amphitheatre City of London, EC2 11 6. Mosaic Pavement City of London, EC3 13 7. London’s Last Roman Citizen 14 Trafalgar Square, WC2 Chapter 2: Saxon Lundenwic 17 8. Saxon Arch City of London, EC3 18 9. Fish Trap Lambeth, SW8 20 10. Grim’s Dyke Harrow Weald, HA3 22 11. Burial Mounds Greenwich Park, SE10 23 12. Crucifixion Scene Stepney, E1 25 13. ‘Grave of a Princess’ Covent Garden, WC2 26 14. Queenhithe City of London, EC3 28 Chapter 3: Norman London 31 15. The White Tower Tower of London, EC3 32 16. Thomas à Becket’s Birthplace City of London, EC2 36 17. -

An Article in Southwark Magazine

Attractions Attractions powered Universal Testing Machine he built with the place. It’s astonishing that it’s still is preserved. here, and it’s so important that it survives. It’s This pioneering machine was historically a crucial part of the legacy of why buildings used for testing the suitability of building and bridges stand up, and underpins the materials for major infrastructure projects world’s standard of engineering established in that include Hammersmith Bridge and this building in Southwark Street.” Wembley Stadium. Museum trustee Sarah Jarvis says: “What OLD OPERATING THEATRE David was doing was very controversial at the When visitors head up the narrow 52-step time, as he was going against the way people staircase in the Old Operating Theatre, they were working. He was saying the only way to will be rewarded with a unique chance to ensure building and construction materials learn about the history of medicine. are safe is to test them rigorously and The oldest surviving surgical theatre in objectively, and to basically build on fact – Europe is tucked away next to the iconic not opinion.” Shard building, and is housed in the attic The volunteer-run museum opens on of the old St Thomas Hospital’s 18th the first Sunday and the third Wednesday of century church. every month, and regularly features as part of Sarah Corn is a year into her role as events such as Open House, London History director of this popular venue that opens Day and the Thames festival. seven days a week and annually has around Jarvis says Kirkaldy Testing Museum is 40,000 visitors. -

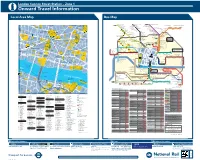

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map Palmers Green North Circular Road Friern Barnet Halliwick Park 149 S GRESHAM STREET 17 EDMONTON R 141 1111 Guildhall 32 Edmonton Green 65 Moorgate 12 A Liverpool Street St. Ethelburga’s Centre Wood Green I 43 Colney Hatch Lane Art Gallery R Dutch WALTHAMSTOW F for Reconcilation HACKNEY 10 Church E Upper Edmonton Angel Corner 16 N C A R E Y L A N E St. Lawrence 17 D I and Peace Muswell Hill Broadway Wood Green 33 R Mayor’s 3 T 55 ST. HELEN’S PLACE for Silver Street 4 A T K ING S ’S ARMS YARD Y Tower 42 Shopping City ANGEL COURT 15 T Jewry next WOOD Hackney Downs U Walthamstow E E & City 3 A S 6 A Highgate Bruce Grove RE 29 Guildhall U Amhurst Road Lea Bridge Central T of London O 1 E GUTTER LANE S H Turnpike Lane N St. Margaret G N D A Court Archway T 30 G E Tottenham Town Hall Hackney Central 6 R O L E S H GREEN TOTTENHAM E A M COLEMAN STREET K O S T 95 Lothbury 35 Clapton Leyton 48 R E R E E T O 26 123 S 36 for Whittington Hospital W E LOTHBURY R 42 T T 3 T T GREAT Seven Sisters Lea Bridge Baker’s Arms S T R E E St. Helen S S P ST. HELEN’S Mare Street Well Street O N G O T O T Harringay Green Lanes F L R D S M 28 60 5 O E 10 Roundabout I T H S T K 33 G M Bishopsgate 30 R E E T L R O E South Tottenham for London Fields I 17 H R O 17 Upper Holloway 44 T T T M 25 St. -

Cetacean Exploitation in Roman and Medieval London Van Den Hurk, Youri; Rielly, Kevin; Buckley, Mike

University of Groningen Cetacean exploitation in Roman and medieval London van den Hurk, Youri; Rielly, Kevin; Buckley, Mike Published in: Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.102795 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2021 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Hurk, Y., Rielly, K., & Buckley, M. (2021). Cetacean exploitation in Roman and medieval London: Reconstructing whaling activities by applying zooarchaeological, historical, and biomolecular analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 36, [102795]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.102795 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal.