{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-Merchandising Gives Consumers Solutions

Cross-Merchandising Gives Consumers Solutions Millennials crave healthy but interesting snack combinations By Bob Johnson display their foods in combination rackers and cheese, bread and deli cross-merchandising, items C with related items. wine, and more recently hummus that make for a quick but nutri- "Our field team consistently and pita go together in consumers’ tious snack satisfy the Millennial looks for opportunities to improve eyes, in the deli display. in us. our customers' ring size and Many new and interesting The Millennials are snacking overall profitability by cross-mer- mixes can be effectively merchan- because they don't have time, and chandising with pre-packed deli dised together in the deli if they if they're going to snack, they meats and cheeses, sliced and combine to answer a question. want healthier snacks," says Paul dried meats, hummus, spreadable "The most effective cross-mer- Cipolla, president of Plocky's Fine cheese and various dips: says Eric chandising is a presentation that Snacks in Hinsdale, IL. "The trend Van De Wal, vice president of provides a complete pairing the last four or five years has been marketing at The Snack Factory in solution to the customer," says toward the healthier snacks." Princeton, NJ. Cara Figgins, vice president at High nutritional value and clean Industry experts recommend Partners, a Kent, WA-based labels matter in the eyes of the displaying a variety of interesting cracker company "With effective generation setting the standard in items that can be quickly and cross-merchandising the retailer the deli. easily assembled into an exciting could increase from selling just Plocky's chips are gluten free, meal. -

Exploiting the Installed Base Using Cross-Merchandising and Category Destination Programs

Exploiting the Installed Base Using Cross-Merchandising and Category Destination Programs Xavier Drèze* Stephen J. Hoch** Abstract We investigate two ways to increase sales and customer loyalty by taking advantage of a store’s installed base of current customers. We propose a classification of products into two types. Products of Type 1 are products for which consumers have a loyalty to a specific retailer and as far as possible always shop that retailer for these products. The other products (Type 2) are not associated with any retailer and are bought at whichever retailer consumers happen to shop when they plan or remember to buy the product. With this in mind, we test the potential of two marketing tools to help retailers increase their share of sales of the Type 2 segment. Using a category destination program we show that one can successfully transform Type 2 into Type 1 products. Using cross-merchandising promotions, we show that one can increase the sales of Type 2 products thereby getting a larger share of discretionary purchases than what one would receive from a straight random allocation. Both series of tests yielded significant increases in sales and profits and were deemed successful by the retailers who implemented them. * Xavier Drèze is Assistant Professor of Marketing at the Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California. ** Stephen J. Hoch is John J. Pomerantz Professor of Marketing at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. 2 Exploiting the Installed Base Using Cross-Merchandising and Category Destination Programs Food retailers in the U.S. and Europe face a hostile environment characterized by slow population growth and excess retail capacity. -

Masters of Merchandising Supplement Masters of Merchandising

Sponsored by 8th Annual MASTERS OF MERCHANDISING SUPPLEMENT MASTERS OF MERCHANDISING As retailers consolidate, they are in a position to expect more support from producers, and intellectual capital is just about the most valuable support one can provide. Each vendor worked hard to produce a piece of advice for the industry on how to more effectively merchandise the product category at hand. By sharing 8th Annual knowledge acquired while working with retailers throughout North America, these vendors help retailers move more product, help producers find outlets for production and help the world by encouraging a more healthful diet. Increasing sales of fruits and vegetables is not only a matter of big pro- MASTERS OF nouncements, such as the Fruits & Veggies — More Matters! program. Sales in general can increase only if sales of specific items increase. That means knowing how to build consumer trial and how to offer the most effective assortment; it MERCHANDISING means knowing how to market things on a day-to-day basis and how to do some out-of-the-box things just to keep consumer interest high. SUPPLEMENT Retailers, please take the time to review this offering carefully. When did you Every once in a while, the opportunity presents itself to do well while also last think about how to increase sales of celery? Or plantains? Or leafy greens? doing good. Such is the case with this, our eigth annual Masters of Merchandis- Here is a chance to think of things in a different way. When did you last really ing supplement. The industry owes a tip of the hat to the collection of industry consider how to best sell bananas — was it when you were a produce department leaders who elected to invest with us in a marketing vehicle that is both promo- manager 10, 20 or 30 years ago? Here is an opportunity to revisit old subjects tional and educational. -

Roadside Stand Marketing of Fruits & Vegetables

The University of Georgia Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Road Side Stand Marketing of Fruits and Vegetables Prepared by: Kent Wolfe & Sharon Kane August 2013 CR- 13-05 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Marketing Trends and Market Potential ......................................................................... Page 1 Customer Profile and Statistics ......................................................................................... Page 6 Merchandising Tactics....................................................................................................... Page 9 Advertising, Publicity and Promotion.............................................................................. Page 17 Salesmanship and the Customer....................................................................................... Page 35 Marketing Budget .............................................................................................................. Page 37 Summary of Objectives and Tactics ................................................................................. Page 38 Appendix A New Leads Format ..................................................................................... Page 41 Appendix B Promotional Suggestions ............................................................................ Page 43 Appendix C Trademark Information ............................................................................. Page 45 Introduction Producers are looking for alternative -

How Merchandising and Layout of Ikea Influence the Consumer Behavior?

HOW MERCHANDISING AND LAYOUT OF IKEA INFLUENCE THE CONSUMER BEHAVIOR? João Pedro Dias Soares Santos Project submitted as partial requirement for the conferral of Master in Management Supervisor: Prof. Susana Maria dos Santos Henriques Marques, Assistant Professor, Marketing, Operations and General Management Department September 2019 Resumo Esta tese é um projeto empresa focado nas áreas de marketing, merchandising e comportamento do consumidor adaptadas à Ikea. O comportamento do consumidor é estudado com muita frequência e abordado por muitas perspectivas devido à sua elevada importância. A estratégia e ferramentas de marketing utilizadas podem ter grande influência na imagem que o cliente tem da empresa, assim como a estratégia de comunicação visual definida é crucial para divulgar a mensagem. O foco principal deste estudo é analisar como o merchandising e o layout da loja influenciam o comportamento do cliente, especificamente nas lojas Ikea. Deste modo, é pertinente entender se o layout da loja e as caraterísticas de loja são adequados para um cliente cada vez mais exigente. Para entender as perceções dos consumidores, foram testados muitos aspetos da experiência de marketing e loja da Ikea. Após a análise dos resultados conclui-se que a Ikea tem uma presença de marketing bastante vincada para o consumidor e quase todas as variáveis da loja têm um efeito positivo no consumidor. Por fim, foram apresentadas algumas sugestões como: desenvolver a conexão digital com o consumidor; A segunda recomendação consiste numa alteração no design da loja: nesta ótica pretende-se atender à necessidade da criação de um caminho mais curto e prático para visitar a loja; A terceira recomendação consiste na elaboração de showrooms virtuais nas lojas, dando a oportunidade de armazenar mais material; A quarta recomendação é a execução de produtos de classe premium e ainda elaboração de uma classe de produtos personalizada. -

Module 1: the Importance of Merchandising

Module 1: The Importance of Merchandising Merchandising, or how products are displayed in the store, plays a critical role in the overall success of your business. After all, when customers come into your store, you want them to buy. Effective merchandising is a tool that gets them closer to that purchase decision. But having effective merchandising demands discipline and planning. It’s hard work. You must pay attention to detail on a daily basis. You also must realize that many of your competitors have effective merchandising. That means your customers are used to seeing it, so they expect it from you, too. In this course, we’ll discuss the techniques and best practices that make up an effective merchandising strategy. We’ll begin by talking about why merchandising is so important. Merchandising makes several important contributions to your store. It increases sales by making a store appealing to your customers. It improves profitability by generating more margin dollars. It controls costs by improving the productivity of the salesfloor as well as each employee. Appeals to Customers • Good merchandising makes shopping easier for customers and gives them reasons to come back often and spend more money. Remember that many consumers may not consider shopping fun. A merchandiser’s goal is to take the hassle out of shopping and make it easier. • Good merchandising can also create customer loyalty. Consumers shop where they feel certain they can find the merchandise they want. They will be loyal to your store if you can create a pleasing shopping experience and provide what they need. -

Mini-Market Analysis

Mini-Market Analysis Executive Summary through an in-store mapping project; and • Estimates (in current-year dollars) of the retail buying As everyone in Frisco knows well. Frisco is one of the fastest-growing power of future Frisco residents, based on the City’s cities in the US. projections of population growth. But, Frisco’s downtown was developed for a town of 1,000 – not the We also incorporated information from meetings with over 100 city of 170,000 it is today – and, it is having growing pains. The city’s community representatives and from two online surveys. rapid growth has triggered a chain of changes downtown – changes We found a number of interesting data that help understand how in traffic congestion, business composition, public image. In 2017, much new market demand might exist for retail goods and services to help explore potential solutions to these and other challenges the in the years ahead, how much new retail and mixed-used space this district is facing, and to outline some direction for the downtown’s new demand might support, and the types of shopping experiences future development, the City engaged Gateway Planning, a Dallas- Frisco’s residents and visitors are likely to prefer. based urban planning firm, to help create a new comprehensive plan to guide downtown Frisco’s development, and Gateway invited our The most significant finding is this: We found that every new household firm, the Community Land Use + Economics Group, to collaborate on that moves to Frisco brings with it over $13,800 in new market demand downtown economic development and management issues. -

Merchandising Trends Achieving Differentiation with a Shopper-Centric Approach

Merchandising Trends Achieving Differentiation with a Shopper-Centric Approach JANUARY 2011 03 Executive Summary 04 Introduction 05 Merchandising Activity 13 Merchandising Effectiveness 15 Merchandising Tactics 17 Trends to Watch 19 Conclusions 21 Resources 1 Merchandising Trends: Achieving Differentiation with a Shopper-Centric Approach Creative Merchandising Critical to CPG and Retail Success in 2011 The new year creates an opportunity to review product and retail strategies with a view toward continuous improvement. Nowhere is this more relevant or important than in merchandising strategies. While experts are still writing their post mortems on the 2010 holiday season, it is clear that consumer spending exhibited a strength not seen since 2006. What remains to be determined, however, is whether the holidays represented a one time splurge from shoppers with “frugal fatigue” or a genuine uptick in attitudes and behaviors that will carry over into the new year. It is also unclear whether gift purchasing activity will translate into increased sales of traditional consumer packaged goods, such as grocery, health or beauty aid items. SymphonyIRI anticipates shoppers will remain conservative in their purchasing habits, but evolve their definition of “value” slowly away from the almost singular focus on price that has shaped behavior for the past three years. The new focus will be one that integrates other factors, such as ingredients to support increased health & wellness, packaging and convenience. The challenges for those leading merchandising efforts are multifold. They must determine which shopper segments are motivated by which types of merchandising activities, typically a combination of price, feature and display activities. Within each segment, they must gauge which products generate the greatest sales volume lift from each type of support. -

In Merchandising

As seen in WHO’S WHO in Merchandising More than 100 consumer product manufacturer and retail executives are represented in this year’s list of noteworthy merchandising professionals, all of whom develop in-store solutions that stand up to the challenges of today’s dynamic retail environment. Describe the structure of your organization as it relates to merchandising, including how you interact with shopper marketing and with insights. WOOD: I manage an amazing team of Mars Wrigley as- sociates who specialize in different types of displays as well as some very talented vendor partners and agencies that help us create best-in-class displays. Data and in- sights are the first lens we use when creating anything, so we work closely with our insights team to make sure our solutions are meeting a specific category or consumer need. We also have a strong connection with our shopper team to make sure we incorporate both the national con- sumer promotions as well as specific shopper programs into our display plans. The relationship between display and shopper is critical in optimizing your in-store condi- tions. How does your company define success for its in- store marketing programs? Photo by Steve Hockstein WOOD: We believe our products create special moments and smiles for our consumers. Display is a fantastic ve- MARS WRIGLEY CONFECTIONERY: hicle to live into that belief by creating those points of interruption in-store to remind shoppers how fun and enjoyable our brands are. JASON WOOD, Director of Display I would say a successful program is one that not only drives sales for Development Mars but also enables us to grow the category. -

Cross-Merchandising to Boost Holiday Potato Sales NO

NO. 19 Cross-merchandising to boost holiday potato sales NO. 19 NO. 19 In test programs at six retail chains last year with limited mar- keting, a joint Idaho® potato and Country Crock® promotion drove growth in both volume and sales for potatoes, the most cooked dish with Country Crock® (after spreading on toast). The perfect pair This year, the new “Buy, Get, Give” promotion will receive national marketing support that includes in-store signage, FSIs, Idaho® potatoes and and a new Country Crock® television commercial featuring a mashed potatoes dish. Country Crock® “Last year’s test program was very successful, and we’re antici- partner for a holiday pating an even bigger and better promotion this year with the wider visibility from the marketing support we’ll be adding,” says promotion with appeal Seth Pemsler, vice president, Retail/International, Idaho Potato Commission. “The ‘Buy, Get, Give’ promotion puts the price Idaho® potatoes—the only branded spud in the market—and of premium Idaho® potatoes well under the price of non-Idaho Country Crock®, the brand that has been bringing delicious, potatoes or retail competitors’ potatoes. In addition, the shop- buttery spreads to American tables for more than 30 years, per and retailer can feel good about helping to give to a family in have teamed up for the irresistible new “Buy, Get, Give” cou- need during the holidays, thanks to the new charity tie-in with pon promotion* running from Oct. 1 through Nov. 30: Feeding America.” BUY: any two Country Crock® 45-ounce spreads Positioning Country Crock® Original buttery spread near Idaho® GET: a free bag of Idaho® potatoes up to $2 potatoes in the produce department also makes it a snap for shop- pers to grab both products and the promotional coupon. -

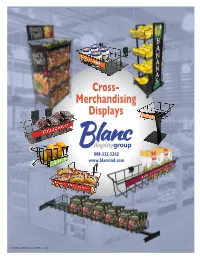

Cross- Merchandising Displays

Cross- Merchandising Displays 888-332-5262 www.blancind.com ©2018 Blanc Industries, Inc. All rights reserved. Cross merchandising: optimizing sales opportunities. Chip and Avocado Display* - 48”H x 24”W x 16”D A complete package, this 3-shelf wire fixture has plenty of room to display packaged chips, while its mesh-lined (for freshness) top tray shelf holds avocados. Side graphics and header finish the look. Chip and Avocado Display*. 48”H x 24”w x 16”d 1-4 5-24 25-49 50-99 100+ #B2730020 $143.50 $126.00 $114.80 $100.45 $86.00 Display Only #B3210159 $57.00 $50.16 $45.60 $39.90 $34.21 Graphic Only #B2730021 $200.00 $176.00 $160.40 $140.35 $120.25 Display and Graphic *Packed one per carton. Price includes mesh liner for top shelf. Strawberries and Dessert Pie Shells Display* - 48”H x 24”W x 131⁄2”D Dessert in a dash?! Yes, with this “berry” special wire fixture with graphics— header, sides, shelf channel. Stack prepared dessert shells on shelves and fresh berries on top, then watch them disappear! Strawberries and Dessert Pie Shells Display*. 48”h x 24”w x 13 1⁄2”d 1-4 5-24 25-49 50-99 100+ #B2730022 $141.00 $124.00 $112.80 $98.70 $84.60 Display Only #B3210160 $51.00 $44.88 $40.80 $35.70 $30.61 Graphic Only #B2730023 $192.00 $168.90 $153.60 $134.40 $115.25 Display and Graphic *Packed one per carton. Price includes mesh liner for top shelf. -

CHEESE Mono2w

MONOGRAPH CHEESE MANAGEMENT CATEGORY MANAGEMENT FOR CHEESE USDEC Summary: Dairy Case Management Toolkit Developed by David Bishop and Willard Bishop Consulting, Ltd. As consumers’ purchasing products. Understanding the category UNDERSTANDING gives retailers insights into trends power increases, eating CATEGORY MANAGEMENT that can help increase sales. patterns change and Category management is defined Because shelf space is so precious, demand for cheese rises. as “a joint retailer-supplier process savvy retailers use category Consumers appreciate for evaluating and managing categories management to make decisions cheese because it’s versatile, as separate business units by focusing about products in the context on delivering consumer value and of an overall strategy. For instance, functional, convenient, developing and monitoring targeted if their strategy is to increase traffic, tasty, nutritious and a strategies for profitable growth.” category management can help identify the best way to do so. good value. That presents In short, category management Or, if their strategy is to boost is an evaluation tool that helps an opportunity for all the size of transactions, category retailers understand the relative management can reveal that as well. segments of the supply profitability of current and new chain — manufacturer, distributor, retailer — to work together to expand sales and profits. Through the use of category management, retailers can properly align the cheese case to serve their customers. 1 e1.1 MONOGRAPH ■ CHEESE MANAGEMENT THE CATEGORY UNDERSTANDING THE MANAGEMENT PROCESS CHEESE CASE Category management comprises an The dairy case is one of the most important eight-step process: sections in the store; more than two-thirds 1. Define the category of U.S.