Legislative History, 1920-1996: Tallgrass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

JOSH SIEGEL Line Producer / UPM Directors Guild of America, Producers Guild of America

Screen Talent Agency 818 206 0144 JOSH SIEGEL Line Producer / UPM Directors Guild of America, Producers Guild of America Josh Siegel knew at an early age he wanted to make movies. Proactively, he raised money while at Johns Hopkins University to create his first film. Siegel has since gone on to produce more than 20 projects, and budgeted in excess of fifty, with budgets of $250k to $30m. His pleasant personality, wit and ability were key in his appointment as head of production for Hannibal Pictures. Josh intimately knows all the stages of production from development through production, post and distribution. He knows how to make your money appear on screen and where you can cut to save funds. And he can do it all with a smile. A member of both the PGA and the DGA, Josh lives in Los Angeles and is available for work worldwide. selected credits as line producer production director / producer / production company SHOT Noah Wyle, Sharon Leal Jeremy Kagan / Josh Siegel / AC Transformative Media A ROLE TO DIE FOR (in prep) John Asher / Conrad Goode / ARTDF Films ANY DAY Eva Longoria, Tom Arnold, Sean Bean, Kate Walsh Rustam Branaman / Andrew Sugerman / Jaguar Ent. BETWEEN Poppy Montgomery (shot entirely in Mexico) David Ocanas / Frank Donner / Lifetime TV RUNNING WITH ARNOLD Alec Baldwin (documentary) Dan Cox / Mike Gabrawy / Endless World Films THE LAST LETTER William Forsythe, Yancy Butler Russell Gannon / Demetrius Navarro / MTI PURPLE HEART William Sadler, Mel Harris Bill Birrell / Russell Gannon / Vision Films OH, MR. FAULKNER, DO YOU WRITE? John Maxwell Jimbo Barnett (prod/director) / MaxBo television 24 Carlos Bernard, Xander Berkeley (DVD bonus episode) Jordan Goldman / Manny Coto, Evan Katz / Fox GUTSY FROG Mischa Barton, Julie Brown Mark A.Z.Dippé / Kevin Jonas, Alan Sacks / Jonas Bros. -

An Ambitious New Plan Offers Delta Water and Economic Hope for the San Joaquin Valley

August 12, 2020 Western Edition Volume 2, Number 30 An ambitious new plan offers Delta water and economic hope for the San Joaquin valley The San Joaquin Valley is bracing for the economic impacts to come from implementing the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act over the next 20 years. Without changes, the regulation could lead to more than a million acres of fallowing and as much as $7 billion in lost revenues every year, with the worst financial impacts rippling down to California’s most disadvantaged communities, according to a report released earlier this year. With this reality, a coalition has emerged around a complex and ambitious approach to bring water to the valley, one that could head off the A new plan takes a different approach to Delta water flows. (Photo of the Sacramento Delta, courtesy of the Department of Water worst effects of SGMA for farmers, the Resources) environment and communities. “We've already started,” said Scott Hamilton, an agricultural economist who works as a consultant for the coalition known as the Water Blueprint for the San Joaquin Valley. “But it’s a process that's going to take quite a bit of time and is fairly difficult.” During a Fresno State seminar series on water infrastructure on Tuesday, Hamilton outlined a sweeping new approach that would pull excess flows from the Delta through a fish-friendly alternative to pumping, then funnel that water through new extensions to existing canals and store it using strategic groundwater recharge projects. “None of it is cheap,” warned Hamilton. “We are now looking at around a $9-billion program for the valley.” 1 He acknowledged the success of the plan hinges on one critical leap of faith: gaining approval from environmental and social justice groups to pull more water from the Delta. -

142000 IOP.Indd

NOVEMBER 2004 New Poll Released Director’s Search Begins Justice Scalia Visits the Forum Nader Visits the Forum Skirting Tradition Released Campaign 2004 Comes to Harvard Hundreds of students attend a Debate Watch in the JFK Jr. Forum Welcome to the Institute of Politics at Harvard University P HIL S HARP , I NTERIM D IRECTOR I was thrilled to return to the Institute of Politics for the fall 2004 semes- ter while a new long-term director is recruited. As a former IOP Director (1995-1998), I jumped at the chance to return to such a special place at an important time. This summer, IOP Director Dan Glickman, Harvard students, and IOP staff went into high gear to mobilize, inspire, and engage young people in politics and the electoral process. • We hosted events for political powerbrokers during the Democratic and Republican National Conventions. • We are working to ensure all Harvard voices are heard at the polls through our dynamic and effective H-VOTE campus vote pro- gram, as well as coordinating the voter education and mobilization activities of nearly 20 other schools across America, part of our National Campaign for Political and Civic Engagement. • Our Resident Fellows this semester are an impressive group. They bring experiences from media, to managing campaigns, to the Middle East. See inside for more information on our exciting fellows. • A survey we conducted with The Chronicle of Higher Education found that most of America’s college campuses are politically active, but 33% of schools fail to meet federal requirements facili- tating voter registration opportunities for students. -

Entire Issue (PDF 792KB)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 166 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, OCTOBER 5, 2020 No. 173 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Tuesday, October 6, 2020, at 9 a.m. Senate MONDAY, OCTOBER 5, 2020 The Senate met at 4:30 p.m. and was to the Senate from the President pro Utah, the senior Senator for Wisconsin, called to order by the Honorable ROGER tempore (Mr. GRASSLEY). and the junior Senator for North Caro- F. WICKER, a Senator from the State of The senior assistant legislative clerk lina, who are currently working from Mississippi. read the following letter: home. The standard cliche would say f U.S. SENATE, that these past few days have provided PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, a stark reminder of the dangers of this PRAYER Washington, DC, October 5, 2020. terrible virus, but the truth is that our To the Senate: Nation did not need any such reminder. The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, fered the following prayer. More than 209,000 of our fellow citi- of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby zens have lost their lives. Millions have Let us pray. appoint the Honorable ROGER F. WICKER, a Mighty God, You are our dwelling Senator from the State of Mississippi, to per- battled illness or had their lives dis- place and underneath are Your ever- form the duties of the Chair. -

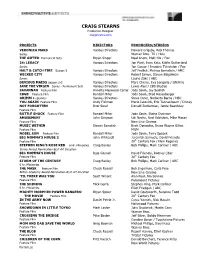

CRAIG STEARNS Production Designer Craigstearns.Com

CRAIG STEARNS Production Designer craigstearns.com PROJECTS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS VERONICA MARS Various Directors Howard Grigsby, Rob Thomas Series Warner Bros. TV / Hulu THE GIFTED Permanent Sets Bryan Singer Neal Ahern, Matt Nix / Fox 24: LEGACY Various Directors Jon Paré, Evan Katz, Kiefer Sutherland Series Jon Cassar / Imagine Television / Fox HALT & CATCH FIRE Season 3 Various Directors Jeff Freilich, Melissa Bernstein / AMC WICKED CITY Various Directors Robert Simon, Steven Baigelman Series Laurie Zaks / ABC DEVIOUS MAIDS Season 2-3 Various Directors Marc Cherry, Eva Longoria / Lifetime JANE THE VIRGIN Series - Permanent Sets Various Directors Lewis Abel / CBS Studios SAVANNAH Feature Film Annette Haywood-Carter Jody Savin, Jay Sedrish CBGB Feature Film Randall Miller Jody Savin, Brad Rosenberger GRIMM 8 episodes Various Directors Steve Oster, Norberto Barba / NBC YOU AGAIN Feature Film Andy Fickman Mario Iscovich, Eric Tannenbaum / Disney NOT FORGOTTEN Dror Soref Donald Zuckerman, Jamie Beardsley Feature Film BOTTLE SHOCK Feature Film Randall Miller Jody Savin, Elaine Dysinger AMUSEMENT John Simpson Udi Nedivi, Neal Edelstein, Mike Macari Feature Film New Line Cinema MUSIC WITHIN Steven Sawalich Brett Donowho, Bruce Wayne Gillies Feature Film MGM NOBEL SON Feature Film Randall Miller Jody Savin, Terry Spazek BIG MOMMA’S HOUSE 2 John Whitesell Jeremiah Samuels, David Friendly th Feature Film 20 Century Fox / New Regency STEPHEN KING’S ROSE RED 6 Hr. Miniseries Craig Baxley Bob Phillips, Mark Carliner / ABC Emmy Award Nomination-Best Art Direction BIG MOMMA'S HOUSE Raja Gosnell David Friendly, Rodney Liber th Feature Film 20 Century Fox STORM OF THE CENTURY Craig Baxley Bob Phillips, Mark Carliner / ABC 6 hr. -

1991-05-09 John Laware Testimony to Committee on Banking.Pdf

ECONOMIC IMPUCATIONS OF THE "TOO BIG TO FAIL" POLICY HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON ECONOMIC STABILIZATION OF THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, FINANCE AND UEBAN AFFAIKS HOUSE OF KEPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SECOND CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MAY 9, 1991 Printed for the use of the Committee on Banking, Finance and Urban Affairs Serial No. 102-31 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 ISBN 0-16-035335-1 HOUSE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, FINANCE AND URBAN AFFAIRS HENRY B. GONZALEZ, Texas, Chairman FRANK ANNUNZIO, Illinois CHALMERS P. WYLIE, Ohio STEPHEN L. NEAL, North Carolina JIM LEACH, Iowa CARROLL HUBBARD, JR., Kentucky BILL McCOLLUM, Florida JOHN J. LAFALCE, New York MARGE ROUKEMA, New Jersey MARY ROSE OAKAR, Ohio DOUG BEREUTER, Nebraska BRUCE F. VENTO, Minnesota THOMAS J. RIDGE, Pennsylvania DOUG BARNARD, JR., Georgia TOBY ROTH, Wisconsin CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York ALFRED A. (AL) McCANDLESS, California BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts RICHARD H. BAKER, Louisiana BEN ERDREICH, Alabama CLIFF STEARNS, Florida THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware PAUL E. GILLMOR, Ohio ESTEBAN EDWARD TORRES, California BILL PAXON, New York GERALD D. KLECZKA, Wisconsin JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania TOM CAMPBELL, California EUZABETH J. PATTERSON, South Carolina MEL HANCOCK, Missouri JOSEPH P. KENNEDY II, Massachusetts FRANK D. RIGGS, California FLOYD H. FLAKE, New York JIM NUSSLE, Iowa KWEISI MFUME, Maryland RICHARD K. ARMEY, Texas PETER HOAGLAND, Nebraska CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming RICHARD E. NEAL, Massachusetts CHARLES J. LUKEN, Ohio BERNARD SANDERS, Vermont MAXINE WATERS, California LARRY LAROCCO, Idaho BILL ORTON, Utah JIM BACCHUS, Florida JAMES P. -

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 141 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, APRIL 7, 1995 No. 65 House of Representatives The House met at 11 a.m. and was PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE DESIGNATING THE HONORABLE called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the FRANK WOLF AS SPEAKER PRO pore [Mr. BURTON of Indiana]. TEMPORE TO SIGN ENROLLED gentleman from New York [Mr. SOLO- BILLS AND JOINT RESOLUTIONS f MON] come forward and lead the House in the Pledge of Allegiance. THROUGH MAY 1, 1995 DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO Mr. SOLOMON led the Pledge of Alle- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- TEMPORE giance as follows: fore the House the following commu- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the nication from the Speaker of the House fore the House the following commu- United States of America, and to the Repub- of Representatives: nication from the Speaker. lic for which it stands, one nation under God, WASHINGTON, DC, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. April 7, 1995. WASHINGTON, DC, I hereby designate the Honorable FRANK R. April 7, 1995. f WOLF to act as Speaker pro tempore to sign I hereby designate the Honorable DAN BUR- enrolled bills and joint resolutions through TON to act as Speaker pro tempore on this MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE May 1, 1995. day. NEWT GINGRICH, NEWT GINGRICH, A message from the Senate by Mr. Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

February 9, 1967 HON. RICHARD D. Mccarthy

February 9, 1967 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- SENATE 3281 CONFIRMATIONS FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION APPALACHIAN REGIONAL COMMISSION Executive nominations confirmed by Lowell K. Bridwell, of Ohio, to be Adminis Joe W. Fleming II, of Arkansas, to be Fed the Senate February 9 (legislative day of trator of the Federal Highway Administra eral cochairman of the Appalachian Regional February 8), 1967: tion. Commission. EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS Rail Rapid Transit emphatic yes! The poor and indigent must tegrate pieces. The wide right-of-way is in have ready and economical access to the out appropriate in cities. It wreaks havoc with er communities. This is where many of the existing structures; takes too much off the EXTENSION OF REMARKS employment opportunities these people seek tax rolls, and cuts great swaths through the OF are located. neighborhoods." (Patrick Healy, executive The model city sessions were devoted pri director, National League of Cities.) HON. RICHARD D. McCARTHY marily to the conditions within our core Again, there was the W1lliamsburg Confer OF NEW YORK areas. Through a common effort, many of ence, where Detroit's Mayor Cavanaugh, the problems faced by the forgotten, un President of the National League of Cities, IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES skilled and deprived groups, could be solved. said: "We must keep in mind the necessity Thursday, February 9, 1967 In addition, certain areas outside of our of including a strong component of rapid present city limits are also plagued by pov transit if we are to end up with a balanced Mr. McCARTHY. Mr. Speaker, the erty. These neighboring residents could be transportation system in the comprehensive necessity of rail rapid transit to match helped by the opening of job opportunities plan because huge sums for urban highways America's future transportation needs which were previously limited because of the will never by themselves solve urban trans and requirements was emphasized to me lack of good public transportation. -

Congressional Record—House

H88 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE January 10, 2018 of Fame. The recognition commemo- United States, or under the Territorial mitteewoman and businesswoman; rates the achievements and contribu- Clause, to use the constitutional term. Charlie Rodriguez, State chairman for tions of citizens age 65 and older. In- Our residents are subject to a second the DNC and former senate president; ductees are selected through a state- class citizenship. For all these years, Alfonso Aguilar, president of the wide nomination and judging process. the Federal Government has denied Latino Partnership for Conservative The program distinguishes individuals equal rights to all Puerto Ricans who Principles; and Ivan ‘‘Pudge’’ Rodri- in the areas of community service, edu- have, in war and peace, made countless guez, a Major League Baseball player cation, the work force, and the arts. contributions to our Nation; who have inducted into the Hall of Fame. Helen is a true public servant who bravely fought in every conflict since Puerto Rico has come to this House has devoted many years to serving the the Great War, defending our demo- today to claim the American Dream residents of Madison County and cratic values, yet they are being denied and to fulfill its destiny, to obtain Nameoki Township. Her no-nonsense the right to vote for their Commander- equality within the Nation, and to un- style may have ruffled some feathers in-Chief and have full representation in leash our full potential. Statehood will throughout the years, but she has this Congress. make Puerto Rico stronger, but we, to- never been afraid to fight for her con- A large number of them have made gether, will make the United States a stituents.