The Holdup Game.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOMINATION FORM I NAME Durant

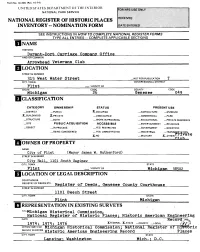

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Durant-Dort Carriage Company Office____________ AND/OR COMMON Arrowhead Veterans Club_______________________ LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 315 West Water Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Flint —. VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Michigan 26 Genesee 049 QCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) X.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL — TRANSEORTATION, f'T'T' Vfl T A X-NO —MILITARY X_OTHER:rriV<llm iihi ' e OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Flint (Mayor James W. Rutherford) STREET & NUMBER City Hall, 1.101 South Saginaw CITY, TOWN STATE Flint VICINITY OF Michigan U8502 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Registrfir of Deeds» Genesee County Courthouse STREET& NUMBER 1101 Beech Street CITY. TOWN STATE Flint Michigan REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTL1Michigan Historical Commissions National Register of Historic Places; Historic American Engineering DATE Record 1974; 1975; 1976________________XFEDERAL -

Gm Livonia Trim Plant in Livonia, Michigan ______10

Repurposing Former Automotive Manufacturing Sites in the Midwest A report on what communities have done to repurpose closed automotive manufacturing sites, and lessons for Midwestern communities for repurposing their own sites. Prepared by: Valerie Sathe Brugeman, MPP Kristin Dziczek, MS, MPP Joshua Cregger, MS Prepared for: The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation June 2012 Repurposing Former Midwestern Automotive Manufacturing Sites A report on what communities have done to repurpose closed automotive manufacturing sites, and lessons for Midwestern communities for repurposing their own sites. Report Prepared for: The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation Report Prepared by: Center for Automotive Research 3005 Boardwalk, Ste. 200 Ann Arbor, MI 48108 Valerie Sathe Brugeman, MPP Kristin Dziczek, MS, MPP Joshua Cregger, MS Repurposing Former Midwestern Automotive Manufacturing Sites Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS _____________________________________________________________ III About the Center for Automotive Research ______________________________________________ iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY _____________________________________________________________ 4 Case Studies ______________________________________________________________________ 5 Key Findings _______________________________________________________________________ 5 INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________________ 7 METHODOLOGY __________________________________________________________________ 7 GM LIVONIA TRIM PLANT IN LIVONIA, MICHIGAN _______________________________________ -

Exhibition Brochure

Detroit Photographs I Detroit Photographs 1 RUSS MARSHALL Detroit Photographs, 1958–2008 Nancy Barr Like a few bars of jazz improvisation, Russ James Pearson Duffy Curator of Photography Marshall’s photographs of city nights, over- time shifts, and solitary moments in a crowd resonate in melodic shades of black and white. In his first museum solo exhibition, we experience six decades of the Motor City through his eyes. Drawn from his archive of 50,000 plus negatives, the photographs in the exhibition celebrate his art and represent just a sample of the 250 works by Marshall acquired by the Detroit Institute of Arts since 2012. Russ Born in 1940 in South Fork, Pennsylvania, Marshall settled in Detroit Detroit Naval aviation still camera photographer. He returned to Detroit Marshall with his family in 1943 and began to pursue photography as a Photographs after military service and continued to photograph throughout the hobby in the late 1950s. Some of his earliest photographs give a city. Ambassador Bridge and Zug Island, 1968, hints at his devel- 2 rare glimpse into public life throughout the city in the post-World 3 oping aesthetic approach. In a long shot looking toward southwest War II years. In Construction Watchers, Detroit, Michigan, 1960, he Detroit, Marshall considers the city’s skyline as an integral part photographed pedestrians as they peer over a barricade to look of the post-industrial urban landscape, a subject he would revisit north on Woodward Avenue, one of Detroit’s main thoroughfares. In throughout his career. The view shows factory smokestacks that other views, Marshall captured silhouetted figures, their shadows, stripe the horizon, and the Ambassador Bridge stretches out over the atmosphere, and resulting patterns of light and dark. -

General Motors

Draft, October 27, 2004 WHEN DOES A CONTRACTUAL ADJUSTMENT INVOLVE A HOLDUP?: THE DYNAMICS OF FISHER-BODY- GENERAL MOTORS Benjamin Klein* I. Introduction Fisher Body-General Motors has become a classic example in economics. Since the brief discussion of the case 35 years ago,1 it has been cited more than one thousand times,2 primarily to illustrate the now generally accepted proposition that vertical integration is more likely when transactors make relationship-specific investments.3 The theoretical and empirical confirmation of this proposition is described by Michael Whinston as “one of the great success stories in industrial organization over the last 25 years.”4 The popularity of the Fisher Body-General Motors case may be difficult to understand since it is merely one of many documented examples of the relationship between vertical integration and specific investments.5 However, the Fisher Body-General Motors case uniquely focuses on the dynamics of this * Professor Emeritus, UCLA. I wish to thank Armen Alchian, Paul Joskow, Victor Goldberg, Tom Hubbard, Scott Masten, Harold Mulherin, Mike Smith, and especially Andres Lerner and Kevin Murphy for comments. Bryan Buskas, Joe Tanimura, Tiffany Truong and Joshua Wright provided research assistance. Earlier versions of the paper were presented at Claremont McKenna College and the ISNIE session of the 2004 ASSA meetings in San Diego. 1 Klein, Crawford and Alchian (1978) at 308-310. 2 There are 1,089 cites to Klein, Crawford and Alchian in the Social Sciences Citation Index, October 19, 2004. 3 [Oliver Williamson cites.] 4 Whinston (2001) at 185. 1 relationship. General Motors was not always vertically integrated with Fisher Body. -

State Has Projects List for Obama

20081215-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 12/12/2008 7:08 PM Page 1 ® WWW.CRAINSDETROIT.COM VOL. 24, NO. 50 DECEMBER 15 – 21, 2008 $2 A COPY; $59 A YEAR ©Entire contents copyright 2008 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved THIS JUST IN State has projects list for Obama Great Lakes Recycling to add 2 new facilities gan of those kinds of projects, because of Roseville-based Great The tally: roads, bridges, schools, energy TRANSIT PLAN the budgetary con- Lakes Recycling plans a BY AMY LANE The plans are being drawn up in Congress. Backers say $10.5B in straints that we’ve grand opening Jan. 13 on a investment will bring CAPITOL CORRESPONDENT There are discussions indicating that as ear- had over the course $12 million, 50,000-square- $42B in development. ly as mid-January, Congress could pass at least of time, and also foot plant in Wayne Coun- LANSING — Being needy might be good. part of a spending plan for Obama to sign on Page 16. some of the bud- ty’s Huron Township. Also, That’s the hope of Michigan business and Jan. 20, his inauguration. getary decisions the company is looking to government officials, as they eye how a state Across Michigan, projects are being tallied made in Washington,” said Arnold Weinfeld, purchase another building with high unemployment, a struggling econo- that include roads and bridges, water and sew- director of public policy and federal affairs for in metro Detroit to expand my and challenged road systems can tap into er, school and university upgrades, and gov- the Michigan Municipal League. -

General Motors 1996-2006 Service Publications Dealer/Wholesale Order Form

GENERAL MOTORS 1996-2006 SERVICE PUBLICATIONS DEALER/WHOLESALE ORDER FORM FACTORY AUTHORIZED INFORMATION For Information Prior To 1996 Contact Us On The Web: www.helminc.com By Mail: HELM, Inc. 14310 Hamilton Ave. Highland Park, MI 48203 Item GM-WHSL-ORD-06 (A)4-06 GENERAL MOTORS TECHNICAL SERVICE ORDERING INFORMATION This catalog contains ordering information for General Motors Technical Service Publications for model years 1996-2006. SERVICE PUBLICATIONS MANUAL DESCRIPTIONS (Continued) Listed publications may be purchased by completing the for fuel-injected gasoline engine fuel and emission order form at back of catalog and mailing it with a check or components. It includes driveability diagnosis. Light Duty money order payable to HELM, INCORPORATED. Orders Truck Fuel and Emissions and Medium Duty Truck Fuel and may be placed toll free for credit card holders only. Emissions Manuals are available. Call 1-800-782-4356. Orders will be filled based on material Unit Repair Manual: Contains overhaul procedures for availability. If we cannot fill the order, monies covering major components once they have been removed from the “out-of-stock” publications will be returned or refunded. vehicle. One manual covers light duty vehicles, and one covers medium duty (and in the past, heavy duty) vehicles. MANUAL DESCRIPTIONS Information for medium and heavy duty truck diesel Service Manual: Will cover full maintenance and repair to engines, drive axles, and transmissions (except SM465 and engine and chassis components. Also contains electrical NP542) is not included. information and specifications. NOTE: Unless otherwise Owner Manual – All Cars and Trucks: This is the driver’s specified, both gasoline and diesel engines are covered in manual (the “glove box booklet”). -

The Fable of Fisher Body Revisited. (Pdf)

The Fable of Fisher Body Revisited Ramon Casadesus-Masanell Daniel Spulber Working Paper 10-081 Copyright © 2010 by Ramon Casadesus-Masanell and Daniel Spulber Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. The Fable of Fisher Body Revisited Ramon Casadesus-Masanell and Daniel Spulber* July 2000 ____________________________ *Harvard Business School Morgan Hall 231, Soldiers Field, Boston, Massachusetts 02163 and Kellogg Graduate School of Management, Northwestern University, 2001 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL, 60208. Introduction It is difficult to hit a moving target. Benjamin Klein (2000) essentially presents a new Fisher Body story despite his contention that “the facts of the Fisher-GM case are shown to be fully consistent with the hold up description provided in Klein, Crawford, and Alchian.” Klein (2000) concedes many of the points made in the articles by Ronald Coase (2000), Robert Freeland (2000) and Ramon Casadesus-Masanell and Daniel F. Spulber (2000). Contrary to Klein et al. (1978), Klein (2000) now acknowledges that the main economic force behind the merger was the need for coordination: “As body design became more important and more interrelated with chassis design and production, the amount of coordination required between a body supplier and its automobile manufacturer customer increased substantially. [...] These economic forces connected with annual model changes ultimately led all automobile manufacturers to adopt vertical integration.” Despite having made this important admission, Klein creates a new fable: the Flint plant problem. -

Roadmap for Auto Community Revitalization

REVITALIZATION RD SUSTAINABLE WAY ROADMAP FOR AUTO COMMUNITY REVITALIZATION A Toolkit for Local Officials Seeking to Clean Up Contamination, Revive Manufacturing, Improve Infrastructure & Build Sustainable Communities iii Roadmap for Auto Community Revitalization Acknowledgements This document is the result of the combined efforts of a partnership between the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office of Brownfields and Land Revitalization (OBLR), the Department of Labor’s (DOL) Office of Recovery for Auto Communities and Workers, and the Manufacturing Alliance of Communities (formerly the Mayors Automotive Coalition (MAC)). DOL, EPA, and the Manufacturing Alliance of Communities acknowledge the assistance provided by OBLR’s contractor, Environmental Management Support (EMS), Inc. In addition, several organizations and individuals provided valuable assistance to the authors of this report. We acknowledge the cooperation of the mayors, city managers, economic development directors, and other officials from localities across the nation that are the drivers of automotive community revitalization. These leaders dedicate themselves to better communities and a better nation. Their struggles, stories and successes form the basis of this roadmap. DOL, EPA and the MAC also acknowledge the cooperation of The Funders’ Network for Smart Growth & Livable Communities, The Ford Foundation, and the Surdna Foundation in their collective efforts to support communities in the revitalization of brownfields. Please note that DOL and EPA do not endorse -

Ford) Compared with Japanese

A MAJOR STUDY OF AMERICAN (FORD) COMPARED WITH JAPANESE (HONDA) AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY – THEIR STRATEGIES AFFECTING SURVIABILTY PATRICK F. CALLIHAN Bachelor of Engineering in Material Science Youngstown State University June 1993 Master of Science in Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering Youngstown State University March 2000 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF ENGINEERING at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY AUGUST, 2010 This Dissertation has been approved for the Department of MECHANICAL ENGINEERING and the College of Graduate Studies by Dr. L. Ken Keys, Dissertation Committee Chairperson Date Department of Mechanical Engineering Dr. Paul A. Bosela Date Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Dr. Bahman Ghorashi Date Department of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering Dean of Fenn College of Engineering Dr. Chien-Hua Lin Date Department Computer and Information Science Dr. Hanz Richter Date Department of Mechanical Engineering ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Dr. Keys, my advisor, for spending so much time with me and providing me with such valuable experience and guidance. I would like to thank each of my committee members for their participation: Dr. Paul Bosela, Dr. Baham Ghorashi, Dr. Chien-Hua Lin and Dr. Hanz Richter. I want to especially thank my wife, Kimberly and two sons, Jacob and Nicholas, for the sacrifice they gave during my efforts. A MAJOR STUDY OF AMERICAN (FORD) COMPARED WITH JAPANESE (HONDA) AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY – THEIR STRATEGIES AFFECTING SURVIABILTY PATRICK F. CALLIHAN ABSTRACT Understanding the role of technology, in the automotive industry, is necessary for the development, implementation, service and disposal of such technology, from a complete integrated system life cycle approach, to assure long-term success. -

Prime Industrial Land for Sale in Lansing, MI

RACER TRUST PROPERTY AVAILABLE IN LANSING, MI 1 UNDER CONTRACT Prime industrial land for sale in Lansing, MI Created November 2, 2012 • Updated November 25, 2019 racertrust.org racertrust.org RACER TRUST PROPERTY AVAILABLE IN LANSING, MI 2 Table of Contents 3 Property Summary 4 Property Location 5 Property Assets 7 Property Details 9 Property Ownership and Recent History 10 Environmental Conditions 11 Conceptual Site Plan 12 Collateral Information, including: Transportation Assets * Access/Linkage * Airports * Port Facilities * Regional Bus Service * Utilities and Natural Gas * Zoning and Business Assistance * Small Business Centers 20 Directory* of Financial Programs and Incentives Available in Michigan 28 Regional Overview, including: Community Snapshot * Workforce * Education * Largest Employers * Medical Facilities and Emergency Services * Links to Helpful Resources 34 Demographic* Information 36 RACER Summary 37 Conditions 38 Transaction Guidelines/Offer Instructions 39 Links for Buyers racertrust.org RACER TRUST PROPERTY AVAILABLE IN LANSING, MI 3 Property Summary Lansing Plant 6 Industrial Land 401 North Verlinden Avenue Lansing, MI 48915 Directly adjacent to two other former GM manufacturing properties owned by RACER — Lansing Plant 2 and Lansing Plant 3 — this property is immediately south of Interstate 69 and north of nearby Interstate 496, and is bordered by railroad tracks on the west, and a residential neighborhood on the east. County: Ingham Land Area: 57.26 acres General Description: Vacant parcel Zoning: H, Heavy Industrial; I, Light Industrial; J, Parking; C, Commercial Tax Parcel Number: 33-01-01-17-101-023; 33-01-01-17-176-001 RACER Site Number: 13003 More information about this property may be reviewed on RACER’s website at www.racertrust.org/Properties/PropertyDetail/Lansing_6_13003. -

TC Publication 209 TARIFF COMMISSION SUBMITS

UNITED STATES TARIFF COMMISSION Washington, D.C. LAPTA-W-12/ TC Publication 209 June 8, 1967 TARIFF COMMISSION SUBMITS REPORT TO THE AUTOMOTIVE AGREEMENT ADJUSTMENT ASSISTANCE BOARD IN ADJUSTMENT ASSISTANCE CASE PERTAINING TO CERTAIN WORKERS OF GENERAL MOTORS CORPORATION'S CHEVROLET PLANT AT NORTH TARRYTOWN, NEW YORK The Tariff Commission today reported. to the Automotive Agreement Adjustment Assistance Board the results of its investigation No. APTA-W-13, conducted. under section 302(e) of the Automotive Products Trade Act of 1965. The Commission's report contains factual informa- tion for use by the Boardl which determines the eligibility of the workers concerned -to apply for adjustment assistance. The workers in this case were employed. in the N. Tarrytown, N.Y., Chevrolet plant of the General Motors Corporation. Only certain sections of the Commission's report can be made public since much of the information it contains was received. in con- fidence. Publication of such information would. result in the disclosure of certain operations of individual firms. The sections of the report that can be made public are reproduced on the following pages. U.S. Tariff Commission, June 8, 1967. Introduction In accordanCe with section 302(e) of the Automotive Products Trade Act of 1965 (79 Stat. 1016), the U.S. Tariff Commission herein reports the results of an investigation (UTA-W-13) concerning the possible dislocation of certain workers engaged in the assembly of automobiles and. trucks at the General Motors Corp.'s Chevrolet assembly plant in North Tarrytown, New York. The Commission instituted. the investigation on April 20, 1967, in response to a request for investigation received. -

SAH in Paris 5 October 11, 2012 Fall Board Meeting

Journal The Society of Automotive Historians, Inc. Issue 255 Electronic March - April 2012 Diamonds Aren’t Forever, Page 12. Inside Date Reminders President’s Message 3 Retromobile 6 June 11, 2012 Scharburg Award Nominations Due SAH Chapter News 3 Pilgrimage to Alsace 8 July 31, 2012 SAH News 4 Book & Media Reviews 10 Valentine Award Nominations Due. Letters 4 Inside the Fisher Body Craftsmen’s Guild August 1, 2012 Bradley Award Nominations Due. The Fisher Body Craftsman’s Guild recap SAH in Paris 5 October 11, 2012 Fall Board Meeting. Cover Vehicle: 1901 Sunbeam-Mabley at the October 12, 2012 www.autohistory.org Louwman Museum. Photo: Lincoln Sarmanian Annual MeetingMarch and- April Awards 2012 Banquet. Journal The Society of Automotive Historians, Inc. Issue 255 March - April 2012 Offi cers SAH Annual Awards J. Douglas Leighton President Benz Award, Chair: Don Keefe, [email protected] John Heitmann Vice President The Carl Benz Award is presented each year for the best article published in the previous calendar year. SAH Robert R. Ebert Secretary Awards of Distinction are awarded for exemplary articles not receiving the Benz Award. Patrick D. Bisson Treasurer 2011 Terry V. Boyce, “1951 Buick XP-300: Mr. Chayne Builds His Dream Car,”in Collectible Automobile 2010 John L. Baeke, M.D, “The Lebarons: Heir Apparent to the Throne,” in The Reunion Board of Directors 2009 Jim Chase, “Packard and Winton: The Transcontinental Rivalry,” in The Packard Cormorant Through October 2012 Thomas S. Jakups, Leslie Kendall, Bradley Award, Chair: Judith Endelman, [email protected] Steve Wilson The James J. Bradley Distinguished Service Award is presented to deserving archives and libraries for exemplary efforts in preserving motor vehicle resource materials.