LAW LIBRARY JOURNAL LAW LIBRARY JOURNAL Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Fifth Annual Rancho Mirage Writers Festival at the Rancho Mirage Library & Observatory

FIFTH ANNUAL RANCHO MIRAGE WRITERS FESTIVAL AT THE RANCHO MIRAGE LIBRARY & OBSERVATORY JANUARY 24–26, 2018 Welcome to the RANCHO MIRAGE WRITERS FESTIVAL! We are celebrating year FIVE of this exciting Festival in 2018! This is where readers meet authors and authors get to know their enthusiastic readers. We dedicate all that happens at this incredible gathering to you, our Angels and our Readers. The Rancho Mirage Writers Festival has a special energy level, driven by ideas and your enthusiasm for what will feel like a pop-up university where the written word and those who write have brought us together in a most appropriate venue — the Rancho Mirage Library and Observatory. The Festival starts fast and never lets up as our individual presenters and panels are eager to share their words and their thoughts. The excitement of books. David Bryant Jamie Kabler In 2013 we began to design the Rancho Mirage Writers Festival. Our Steering Committee kept its objective LIBRARY DIRECTOR FESTIVAL FOUNDER important and clear — to bring authors, their books, and our readers together in this beautiful resort city. In 2018 our mission remains the same, though the Festival has grown and gets even better this year. The writers you read and the books that get us thinking and talking converge at the Festival to make January in the Desert, not only key to our season, but a centerpiece of our cultural life. The Festival is a celebration of the written word. The Festival lives in our award-winning Library. Recent investments in the Library include: Welcome • Windows in the John Steinbeck Room and the Jack London Room that can be darkened electronically making for a better presenter/audience experience. -

Ordering Divine Knowledge in Late Roman Legal Discourse

Caroline Humfress ordering.3 More particularly, I will argue that the designation and arrangement of the title-rubrics within Book XVI of the Codex Theodosianus was intended to showcase a new, imperial and Theodosian, ordering of knowledge concerning matters human and divine. König and Whitmarsh’s 2007 edited volume, Ordering Knowledge in the Roman Empire is concerned primarily with the first three centuries of the Roman empire Ordering Divine Knowledge in and does not include any extended discussion of how knowledge was ordered and structured in Roman juristic or Imperial legal texts.4 Yet if we classify the Late Roman Legal Discourse Codex Theodosianus as a specialist form of Imperial prose literature, rather than Caroline Humfress classifying it initially as a ‘lawcode’, the text fits neatly within König and Whitmarsh’s description of their project: University of St Andrews Our principal interest is in texts that follow a broadly ‘compilatory’ aesthetic, accumulating information in often enormous bulk, in ways that may look unwieldy or purely functional In the celebrated words of the Severan jurist Ulpian – echoed three hundred years to modern eyes, but which in the ancient world clearly had a much higher prestige later in the opening passages of Justinian’s Institutes – knowledge of the law entails that modern criticism has allowed them. The prevalence of this mode of composition knowledge of matters both human and divine. This essay explores how relations in the Roman world is astonishing… It is sometimes hard to avoid the impression that between the human and divine were structured and ordered in the Imperial codex accumulation of knowledge is the driving force for all of Imperial prose literature.5 of Theodosius II (438 CE). -

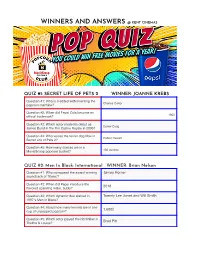

KENT WINNERS and ANSWERS Copy

WINNERS AND ANSWERS @ KENT CINEMAS QUIZ #1: SECRET LIFE OF PETS 2 WINNER: JOANNE KREBS Question #1: Who is credited with inventing the Charles Cretor popcorn machine? Question #2: When did Pepsi Cola become an 1903 official trademark? Question #3: Which actor made his debut as Daniel Craig James Bond in the film Casino Royale in 2006? Question #4: Who voices the terrier dog Max in Patton Oswalt Secret Life of Pets 2? Question #5: How many ounces are in a MovieScoop popcorn bucket? 130 ounces QUIZ #2: Men In Black: International WINNER: Brian Nelson Question #1: Who composed the award-winning James Horner soundtrack of Titanic? Question #2: When did Pepsi introduce the 2018 flavored sparkling water, bubly? Question #3: Which dynamic duo starred in Tommy Lee Jones and Will Smith 1997's Men in Black? Question #4: About how many kernels are in one 1,600!! cup of unpopped popcorn? Question #5: Which actor played the hitchhiker in Brad Pitt Thelma & Louise? QUIZ #3: Toy Story 4 WINNER: Jacob Mix Question #1: What were the names of Harry and Marv the two bungling burglars in Home Alone? Question #2: Which actor voices Gru in Steve Carell Despicable Me? Question #3: Who is NOT a character in Baby Potato Head the Toy Story movie series? Question #4: Complete this jingle from That's A Lot!" the 1930s: "Pepsi-Cola hits the spot, twelve full ounces.... --" Question #5: What was the original Brad's Drink name for Pepsi? QUIZ #4: Annabelle Comes Home WINNER: Ryan Johnston Question #1: In which year was 2017 Annabelle: Creation released? Question #2: True -

Justinian's Redaction

JUSTINIAN'S REDACTION. "Forhim there are no dry husks of doctrine; each is the vital develop- ment of a living germ. There is no single bud or fruit of it but has an ancestry of thousands of years; no topmost twig that does not greet with the sap drawn from -he dark burrows underground; no fibre torn away from it but has been twisted and strained by historic wheels. For him, the Roman law, that masterpiece of national growth, is no sealed book ..... ... but is a reservoir of doctrine, drawn from the watershed of a world's civilization!'* For to-day's student of law, what worth has the half- dozen years' activity of a few Greek-speakers by the Bos- phorus nearly fourteen centuries ago? Chancellor Kent says: "With most of the European nations, and in the new states of Spanish America, and in one of the United States, it (Roman law) constitutes the principal basis of their unwritten or common law. It exerts a very considerable influence on our own municipal law, and particularly on those branches of it which are of equity and admiralty jurisdiction, or fall within the cognizance of the surrogate or consistorial courts . It is now taught and obeyed not only in France, Spain, Germany, Holland, and Scotland, but in the islands of the Indian Ocean, and on the banks of the Mississippi and St. Lawrence. So true, it seems, are the words of d'Agnesseau, that 'the grand destinies of Rome are not yet accomplished; she reigns throughout the world by her reason, after having ceased to reign by her authority?'" And of the honored jurists whose names are carved on the stones of the Law Building of the University of Pennsyl- vania another may be cited as viewing the matter from a different standpoint. -

NEIL KREPELA ASC Visual Effects Supervisor

NEIL KREPELA ASC Visual Effects Supervisor www.neilkrepela.net FILM DIRECTOR STUDIO & PRODUCERS “THE FIRST COUPLE” NEIL KREPELA BERLINER FILM COMPANIE (Development – Animated Feature) Mike Fraser, Rainer Soehnlein “CITY OF EMBER” GIL KENAN FOX/WALDEN MEDIA Visual Effects Consultant Gary Goetzman, Steven Shareshian “TORTOISE AND THE HIPPO” JOHN DYKSTRA WALDEN MEDIA Visual Effects Consultant “TERMINATOR 3: RISE OF THE JONATHAN MOSTOW WARNER BROTHERS MACHINES” Joel B. Michaels, Gale Anne Hurd, VFX Aerial Unit Director Colin Wilson & Cameraman “SCOOBY DOO” RAJA GOSNELL WARNER BROTHERS Additional Visual Effects Supervision Charles Roven, Richard Suckle “DINOSAUR” ERIC LEIGHTON WALT DISNEY PICTURES RALPH ZONDAG Pam Marsden “MULTIPLICITY” HAROLD RAMIS COLUMBIA PICTURES Visual Effects Consult Trevor Albert Pre-production “HEAT” MICHAEL MANN WARNER BROTHERS/FORWARD PASS Michael Mann, Art Linson “OUTBREAK” WOLFGANG PETERSEN WARNER BROTHERS (Boss Film Studio) Wolfgang Petersen, Gail Katz, Arnold Kopelson “THE FANTASTICKS” MICHAEL RITCHIE UNITED ARTISTS Linne Radmin, Michael Ritchie “THE SPECIALIST” LUIS LLOSA WARNER BROTHERS Jerry Weintraub “THE SCOUT” MICHAEL RITCHIE TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX (Boss Film Studio) Andre E. Morgan, Albert S. Ruddy “TRUE LIES” JAMES CAMERON TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX (Boss Film Studio) James Cameron, Stephanie Austin “LAST ACTION HERO” BARRY SONNENFELD COLUMBIA PICTURES (Boss Film Studio) John McTiernan, Steve Roth “CLIFFHANGER” RENNY HARLIN TRISTAR PICTURES Academy Award Nominee Renny Harlin, Alan Marshall “BATMAN RETURNS” -

The Corpus Juris Civilis

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Library Staff ubP lications The oW lf Law Library 2015 The orC pus Juris Civilis Frederick W. Dingledy William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Dingledy, Frederick W., "The orC pus Juris Civilis" (2015). Library Staff Publications. 118. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/libpubs/118 Copyright c 2015 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/libpubs The Corpus Juris Civilis by Fred Dingledy Senior Reference Librarian College of William & Mary Law School for Law Library of Louisiana and Supreme Court of Louisiana Historical Society New Orleans, LA – November 12, 2015 What we’ll cover ’History and Components of the Corpus Juris Civilis ’Relevance of the Corpus Juris Civilis ’Researching the Corpus Juris Civilis Diocletian (r. 284-305) Theodosius II Codex Gregorianus (r. 408-450) (ca. 291) {{ Codex Theodosianus (438) Codex Hermogenianus (295) Previously… Byzantine Empire in 500 Emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565) “Arms and laws have always flourished by the reciprocal help of each other.” Tribonian 528: Justinian appoints Codex commission Imperial constitutiones I: Ecclesiastical, legal system, admin II-VIII: Private IX: Criminal X-XII: Public 529: Codex first ed. {{Codex Liber Theodora (500-548) 530: Digest commission 532: Nika (Victory) Riots Digest : Writings by jurists I: Public “Appalling II-XLVII: Private arrangement” XLVIII: Criminal --Alan XLIX: Appeals + Treasury Watson L: Municipal, specialties, definitions 533: Digest/Pandects First-year legal textbook I: Persons II: Things III: Obligations IV: Actions 533: Justinian’s Institutes 533: Reform of Byzantine legal education First year: Institutes Digest & Novels Fifth year: Codex The Novels (novellae constitutiones): { Justinian’s constitutiones 534: Codex 2nd ed. -

NEIL KREPELA ASC Visual Effects Supervisor

NEIL KREPELA ASC Visual Effects Supervisor www.neilkrepela.net FILM DIRECTOR STUDIO & PRODUCERS “THE FIRST COUPLE ” NEIL KREPELA Berliner Film Companie (Development – Animated Feature) Mike Fraser, Rainer Soehnlein “CITY OF EMBER ” GIL KENAN FOX -WALDEN Visual Effects Consultant Gary Goetzman, Tom Hanks, Steven Shareshian “TORTOI SE AND THE HIPPO” JOHN DYKSTRA WALDEN MEDIA Visual Effects Consultant “MEET THE ROBINSONS” STEPHEN ANDERSON WALT DISNEY ANIMATION Lighting & Composition Dorothy McKim, Bill Borden “TERMINATOR 3: RISE OF THE JONATHAN MOSTOW WARNER BROTHERS MACHINES” VFX Aerial Unit Director Mario F. Kassar, Hal Lieberman, & Cameraman Joel B. Michaels, Andrew G. Vajna, Colin Wilson “SCOOBY DOO ” RAJA GOSNELL WA RNER BROTHERS Additional Visual Effects Supervision Charles Roven, Richard Suckle “DINOSAUR ” ERIC LEIGHTON WALT DISNEY PICTURES Pam Marsden “MULTIPLICITY” (Boss Film Studio) HAROLD RAMIS COLUMBIA PICTURES Visual Effects Consult - Pre-production Trevor Albert “HEAT ” MICHAEL MANN WARNER BROTHERS /FORWARD PASS Michael Mann, Art Linson “OUTBREAK” – (Boss Film Studio ) WOLFGANG PETERSEN WARNER BROTHERS Wolfgang Petersen, Gail Katz, Arnold Kopelson “THE FANTASTICKS ” MICHAEL RITCHIE UNITED ARTISTS Linne Radmin, Michael Ritchie “THE SPECIALIST ” LUIS LLOSA WARNER BROTHERS Jerry Weintraub “THE SCOUT” - (Boss Film Studio) MICHAEL RITCHIE TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX Andre E. Morgan, Albert S. Ruddy Neil Krepela -Continued- “TRUE LIES ” JAMES CAMERON TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX (Boss Film Studio) James Cameron, Stephanie Austin “LAST ACTION -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

Law and Empire in Late Antiquity

job:LAY00 17-10-1998 page:3 colour:0 Law and Empire in Late Antiquity Jill Harries job:LAY00 17-10-1998 page:4 colour:0 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb2 1rp, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, USA http://www.cup.org © Jill D. Harries 1999 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1999 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Plantin 10/12pt [vn] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Harries, Jill. Law and empire in late antiquity / Jill Harries. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0 521 41087 8 (hardback) 1. Justice, Administration of – Rome. 2. Public law (Roman law) i. Title. KJA2700.H37 1998 347.45'632 –dc21 97-47492 CIP ISBN 0 521 41087 8 hardback job:LAY00 17-10-1998 page:5 colour:0 Contents Preface page vii Introduction 1 1 The law of Late Antiquity 6 Confusion and ambiguities? The legal heritage 8 Hadrian and the jurists 14 Constitutions: the emperor and the law 19 Rescripts as law 26 Custom and desuetude 31 2 Making the law 36 In consistory -

After Krüger: Observations on Some Additional Or Revised Justinian Code Headings and Subscripts*)

After Krüger: observations on some additional or revised Justinian Code headings and subscripts*) Der Beitrag stellt Ausschnitte aus Handschriften zusammen, die seit der Ausgabe des Co- dex Justinians 1877 durch Krüger entdeckt wurden, und die Ergänzungen oder Korrekturen an Inskriptionen und Subskriptionen ermöglichen. Die Handschriften sind P. Oxy. XV 1814 (C. 1,11,1-1,16,11 [first edition]), MS Cologne GB Kasten Β no. 130 (C. 3,32,4-12), PSI XIII 1347 (C. 7,16,41-7,17,1), P. Rein. Inv. 2219 (fragments of C. 12,59,10-12,62,4), MS Würzburg Universitätsbibliothek M.p.j.f.m.2 (C. 1,27,1,37-1,27,2,16 and 2,43,3-2,51,2), MS Stuttgart, Württemb. Staatsbibl. Cod. fragm 62 (C. 4,20,12-21,11). This article summarises details of manuscripts identified since the standard 1877 edition of the Justinian Code and containing additions to or revisions of headings and subscripts. The manuscripts are: P. Oxy. XV 1814 (CJ 1,11,1-1,16,11 [first edition]), MS Cologne GB Kasten Β no. 130 (CJ 3,32,4-12), PSI ΧΠΙ 1347 (CJ 7,16,41-7,17,1), P. Rein. Inv. 2219 (fragments of CJ 12,59,10-12,62,4), MS Würzburg Universitätsbibliothek M.p.j.f.m.2 (CJ 1,27,1,37-1,27,2,16 and 2,43,3-2,51,2), MS Stuttgart, Württemb. Staatsbibl. Cod. fragm. 62 (CJ 4,20,12-21,11). I. Introduction - Π. Sixth-century manuscripts a) P. Oxy. XV 1814, b) Cologne GB Kasten Β no. -

Imperial Letters in Latin: Pliny and Trajan, Egnatius Taurinus and Hadrian1

Imperial Letters in Latin: Pliny and Trajan, Egnatius Taurinus and Hadrian1 Fergus Millar 1. Introduction No-one will deny the fundamental importance of the correspondence of Pliny, as legatus of Pontus and Bithynia, and Trajan for our understanding of the Empire as a system. The fact that at each stage the correspondence was initiated by Pliny; the distances travelled by messengers in either direction (as the crow flies, some 2000 km to Rome from the furthest point in Pontus, and 1,500 km from Bithynia);2 the consequent delays, of something like two months in either direction; the seemingly minor and localised character of many of the questions raised by Pliny, and the Emperor’s care and patience in answering them – all these can be seen as striking and revealing, and indeed surprising, as routine aspects of the government of an Empire of perhaps some 50 million people. On the other hand this absorbing exchange of letters can be puzzling, because it seems isolated, not easy to fit into any wider context, since examples of Imperial letters in Latin are relatively rare. By contrast, the prestige of the Greek City in the Roman Empire and the flourishing of the epigraphic habit in at least some parts of the Greek world (primarily, however, the Greek peninsula and the western and southern areas of Asia Minor) have produced a large and ever-growing crop of letters addressed by Emperors to Greek cities and koina, and written in Greek. The collection of Greek constitutions published by J.H. Oliver in 1989 could now be greatly increased.