Chapter 5 Affected Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C&P IDAHO4 8X11 2004.Indd

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Camping and Picnicking on the Service Intermountain Region National Forests of Ogden, Utah Southern Idaho & Western Wyoming 95 90 Lewiston IDAHO Salmon MONTANA 93 55 95 Challis 20 14 93 21 15 20 20 26 Jackson Boise Idaho Falls 20 20 84 Pocatello 189 86 30 Twin Falls Big Piney 93 Montpelier 189 WYOMING 84 15 Kemmerer 80 UTAH 30 30 Ogden 80 Evanston THE NATIONAL FORESTS America’s Great 2 0 0 4 2 0 0 4 Outdoors 1 in your multiple-use National partners in seeing that the National This Land is Your Land Forests. Forests fulfi ll and magnify the intent This guide is provided as an wildernesses, adventure, solitude, For those who prefer a less of their creation. Your partnership introduction to the the camping and scenery enough to saturate your robust trip, how about a scenic drive, decrees the right to enjoy, but not and picnicking opportunities in the aesthetic cravings. photography excursion, bird watch- destroy, any facet of the National National Forests of the Intermoun- A National Forest is more than ing, or a picnic? All these experi- Forest. tain Region. More detailed infor- trees and camping, hiking, fi shing, ences–and more–await you. Forest Supervisors, District mation can be obtained from each and hunting. You can enjoy the Woodcutting, a popular family Rangers, their staffs, and volunteers, National Forest offi ce listed. Two magnifi cence of the mountains; the outing in the Intermountain Region, live and work in the National Forests. key documents that you may wish serenity of the wilderness; the thrill starts early in the summer and con- They will answer your questions, to request are the “National Forest of skiing and kayaking; the miracles tinues through the fall. -

A FISH CONSUMPTION SURVEY of the SHOSHONE-BANNOCK TRIBES December 2016

A FISH CONSUMPTION SURVEY OF THE SHOSHONE-BANNOCK TRIBES December 2016 United States Environmental Protection Agency A Fish Consumption Survey of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes Final Report This final report was prepared under EPA Contract EP W14 020 Task Order 10 and Contract EP W09 011 Task Order 125 with SRA International. Nayak L Polissar, PhDa Anthony Salisburyb Callie Ridolfi, MS, MBAc Kristin Callahan, MSc Moni Neradilek, MSa Daniel S Hippe, MSa William H Beckley, MSc aThe Mountain-Whisper-Light Statistics bPacific Market Research cRidolfi Inc. December 31, 2016 Contents Preface to Volumes I-III Foreword to Volumes I-III (Authored by the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes and EPA) Foreword to Volumes I-III (Authored by the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes) Volume I—Heritage Fish Consumption Rates of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes Volume II—Current Fish Consumption Survey Volume III—Appendices to Current Fish Consumption Survey PREFACE TO VOLUMES I-III This report culminates two years of work—preceded by years of discussion—to characterize the current and heritage fish consumption rates and fishing-related activities of the Shoshone- Bannock Tribes. The report contains three volumes in one document. Volume I is concerned with heritage rates and the methods used to estimate the rates; Volume II describes the methods and results of a current fish consumption survey; Volume III is a technical appendix to Volume II. A foreword to Volumes I-III has been authored by the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes and EPA. The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes have also authored a second foreword to Volumes I-III and the ‘Background’ section of Volume I. -

Nez Perce Tribe) Food Sovereignty Assessment

Nimi’ipuu (Nez Perce Tribe) Food Sovereignty Assessment Columbia River Basin, Showing Lands Ceded by the Nez Perce and Current Reservation Source: Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission http://www.critfc.org/member_tribes_overview/nez-perce-tribe/ Prepared for the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee by Ken Meter, Crossroads Resource Center (Minneapolis) December 2017 Nez Perce Tribe Food Sovereignty Assessment — Ken Meter, Crossroads Resource Center — 2017 Executive Summary The aim of this study is to inform and strengthen Nimi’ipuu (Nez Perce) tribal efforts to achieve greater food sovereignty. To accomplish this purpose, public data sets were compiled to characterize conditions on the reservation and estimate the food needs of tribal members. Tribal leaders were interviewed to identify the significant food system assets, and visions for food sovereignty, held by the Tribe. Finally, the report outlines some of the approaches the Tribe contemplates taKing to increase its food sovereignty. Central to both Nimi’ipuu culture and to the nourishment of tribal members is subsistence gathering of wild foods. This stands at the core of food sovereignty initiatives. Yet tribal leaders are also pursuing plans to build a more robust agricultural system that will feed tribal members. Community gardens have sprung up on the Reservation, and many people maintain private gardens for their own use. Tribal hatcheries and watershed sustainability efforts have been highly successful in ensuring robust fisheries in the Columbia River watershed. Our research found that the 3,536 members of the Nez Perce Tribe have less power over the Reservation land than they would ideally liKe to have, with only 17% of Reservation land owned by the Tribe or tribal members (Local Foods Local Places 2017; Nez Perce Tribe Land Services). -

Heritage Fish Consumption Rates of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes

Heritage Fish Consumption Rates of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes Final Report This final report was prepared under EPA Contract EP W14 020 Task Order 10 and Contract EP W09 011 Task Order 125 with SRA International. Nayak L Polissar, PhDa Anthony Salisburyb Callie Ridolfi, MS, MBAc Kristin Callahan, MSc Moni Neradilek, MSa Daniel S Hippe, MSa William H Beckley, MSc aThe Mountain-Whisper-Light Statistics bPacific Market Research cRidolfi Inc. December 31, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose and Objectives ................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Study Approach ........................................................................................................... 2 2.0 BACKGROUND (authored by the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes) .................................... 3 2.1 Summary of Historical Fish Harvest and Consumption .............................................. 3 2.2 Summary of Causes of Decline in Fish Populations ................................................... 3 3.0 HERITAGE FISH CONSUMPTION RATES (FCRs) .................................................. 6 3.1 Defining Fish Consumption ......................................................................................... 6 3.2 Defining Factors Influencing Consumption Rates ...................................................... 6 3.2.1 Migration Calorie Loss Factor .......................................................................7 -

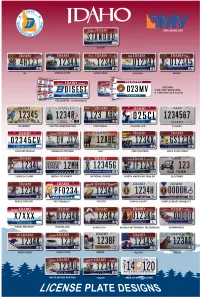

To See a Complete List of All Special Plates Types Available

2021 SPECIAL LICENSE PLATE FUND INFORMATION Plate Program Fund Name Responsible Organization (Idaho Code) Program Purpose Friends of 4-H Division University of Idaho Foundation 4H (49-420M) Funds to be used for educational events, training materials for youth and leaders, and to better prepare Idaho youth for future careers. Agriculture Ag in the Classroom Account Department of Agriculture (49-417B) Develop and present an ed. program for K-12 students with a better understanding of the crucial role of agriculture today, and how Idaho agriculture relates to the world. Appaloosa N/A Appaloosa Horse Club (49-420C) Funding of youth horse programs in Idaho. Idaho Aviation Foundation Idaho Aviation Association Aviation (49-420K) Funds use by the Idaho Aviation Foundation for grants relating to the maintenance, upgrade and development of airstrips and for improving access and promoting safety at backcountry and recreational airports in Idaho. N/A - Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation Biking (49-419E) Funds shall be used exclusively for the preservation, maintenance, and expansion of recreational trails within the state of Idaho and on which mountain biking is permitted. Capitol Commission Idaho Capitol Endowment Income Fund – IC 67-1611 Capitol Commission (49-420A) To help fund the restoration of the Idaho Capitol building located in Boise, Idaho. Centennial Highway Distribution Account Idaho Transportation Department (49-416) All revenue shall be deposited in the highway distribution account. Choose Life N/A Choose Life Idaho, Inc. (49-420R) To help support pregnancy help centers in Idaho. To engage in education and support of adoption as a positive choice for women, thus encouraging alternatives to abortion. -

10. Palouse Prairie Section

10. Palouse Prairie Section Section Description The Palouse Prairie Section, part of the Columbia Plateau Ecoregion, is located along the western border of northern Idaho, extending west into Washington (Fig. 10.1, Fig. 10.2). This section is characterized by dissected loess-covered basalt plains, undulating plateaus, and river breaks. Elevation ranges from 220 to 1,700 m (722 to 5,577 ft). Soils are generally deep, loamy to silty, and have formed in loess, alluvium, or glacial outwash. The lower reaches and confluence of the Snake and Clearwater rivers are major waterbodies. Climate is maritime influenced. Precipitation ranges from 25 to 76 cm (10 to 30 in) annually, falling primarily during the fall, winter, and spring, and winter precipitation falls mostly as snow. Summers are relatively dry. Average annual temperature ranges from 7 to 12 ºC (45 to 54 ºF). The growing season varies with elevation and lasts 100 to 170 days. Population centers within the Idaho portion of the section are Lewiston and Moscow, and small agricultural communities are dispersed throughout. Outdoor recreational opportunities include hunting, angling, hiking, biking, and wildlife viewing. The largest Idaho Palouse Prairie grassland remnant on Gormsen Butte, south of Department of Fish and Moscow, Idaho with cropland surrounding © 2008 Janice Hill Game (IDFG) Wildlife Management Area (WMA) in Idaho, Craig Mountain WMA, is partially located within this section. The deep and highly-productive soils of the Palouse Prairie have made dryland farming the primary land use in this section. Approximately 44% of the land is used for agriculture with most farming operations occurring on private land. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form Bee instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections____________________________________ 1. Name_____________________________ historic Milner Dam and the Twin Falls Main Canal and/or common___N/A______________________________________________________ 2. Location____________________________ street & number N/A_____________________________________N/A_ not for publication city, town Murtaugh JL vicinity of (see Verbal Boundary Description) state Idaho code 016 county S ee item 10 code see item 10 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied X agriculture museum building(s) X private AY unoccupied commercial park X structure (s) both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A in process yes: restricted government scientific N_/A_ being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military 4. Owner of Property name_________Multiple ownership (see continuation sheet) street & number N/A city, town_______N/A______________N/A_ vicinity of______________state Idaho__________ 5. Location of Legal Description______________ courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. See continuation sheet_______________________________ street & number___________N/A______________________________________________ city, town_______________N/A__________________________state -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior ,C£$ PftRKSERVIC National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Pla Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not ap property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcatei instructins. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name: American Falls Reservoir Flooded Townsite other name/site number: 2. Location street & number American Falls Reservoir [ ] not for publication city or town American Falls ______ [ X ] vicinity state: Idaho code: ID county: Power code: 077 zip code: 83211 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 -

Idaho Workforce Information

Idaho Workforce Information Annual Progress Report Reference Period ~ July 1, 2011 to June 30, 2012 Idaho completed all core deliverables in Program Year 2011 as outlined in the Workforce Information Plan abstract. Adjustments, additions and enhancements were made to accommodate customer inquiries and needs and to make Idaho’s workforce information system more effective and sustainable. Idaho’s economic volatility over the last several years has put immense pressure on LMI staff to closely monitor Idaho’s economy and publish insight on directional changes and shifts in an economy that in 2010 and 2011 experienced the worst performance on record in Idaho. The economic climate during this period made it imperative that the staff listen to department customers and provide the data that suit their needs as Idaho navigates through a deep economic recession and attempts to expand. To meet customer needs, the Idaho Department of Labor and the Workforce Development Council are fully engaged in planning and implementing the Workforce Information Plan. The department works directly with the council to identify the labor market information needs of communities and regions throughout the state. The department also presents current research at council meetings and always uses member feedback to make changes to the current plan to better serve local customers and stakeholders. Other than Web metrics, for workforce information alone feedback is mostly in a non-statistical anecdotal format. However an agency-wide comprehensive customer satisfaction research effort was conducted in 2011 that assisted the workforce information team in the development of our products. We have used these findings to assess our web delivery mechanism as well as the research products and data as whole. -

Burley Field Office Business Plan Lud Drexler Park and Milner Historic Recreation Area

U.S. Department of the Interior | Bureau of Land Management | Idaho Burley Field Office Business Plan Lud Drexler Park and Milner Historic Recreation Area June 2020 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Twin Falls District Burley Field Office 15 East 200 South Burley, ID 83318 Burley Field Office Business Plan Milner Historic Recreation Area and Lud Drexler Park I. Executive Summary The following document introduces a proposed fee increase by the Burley Field Office of the Bureau of Land Management for the recreation fee areas it manages in southern Idaho. The need for this action as well as the history of the fee program, expenses generated by the recreation sites and plans for future expenditures are outlined and explained in the pages below. The BLM Twin Falls District has two recreation fee sites, Milner Historic Recreation Area and Lud Drexler Park, both located in the Burley Field Office. The sites are the most popular recreation sites within the District hosting 40,000 plus people annually per site, with visits steadily increasing every year. This visitor increase along with aging infrastructure is contributing to resource damage and decreasing visitor safety and experiences, while budgets are stretched to keep up with maintenance and growing needs for improvements. Milner Historic Recreation Area The Milner Historic Recreation Area (MHRA) is situated along the Snake River, 9 miles west of Burley, Idaho. Both primitive and developed camp sites and boating facilities dot the 4.5-mile shoreline. The area’s basalt cliffs, sagebrush, and grasslands provide habitat to a variety of songbirds and waterfowl. -

Wilderness Management Plan Environmental Assessment

NATIONAL SYSTEM OF PUBLIC LANDS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT United States Department of Agriculture United States Department of the Interior Forest Service Bureau of Land Management Hemingway-Boulders and White Clouds Wilderness Management Plan Environmental Assessment Sawtooth National Forest, Sawtooth National Recreation Area Bureau of Land Management, Idaho Falls District, Challis Field Office October 25, 2017 For More Information Contact: Kit Mullen, Forest Supervisor Sawtooth National Forest 2647 Kimberly Road East Twin Falls, ID 83301-7976 Phone: 208-737-3200 Fax: 208-737-3236 Mary D’Aversa, District Manager Idaho Falls District 1405 Hollipark Drive Idaho Falls, ID 83401 Phone: 208-524-7500 Fax: 208-737-3236 Photo description: Castle Peak in the White Clouds Wilderness In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. -

The Twin Falls Water Story: More Growth, Less Use

The Twin Falls Water Story: More Growth, Less Use In 1746 among the pages of Poor Richard’s Almanac, Benjamin Franklin noted astutely, “When the well is dry, we know the worth of water.” Those who are intimately involved in city planning can agree it’s best to not wait until the well is dry before understanding the many ways water sustains industry, commerce and the well-being of a population. The City of Twin Falls, Idaho, has made water management a priority for decades. As a result, groundwater consumption has gone down even as their population growth continues at a steady pace. The History of Twin Falls Water When exploring the dozens of waterfalls in the Magic Valley including the sprawling, thundering Shoshone Falls, it’s difficult to imagine the area as a parched desert. “The building of Milner Dam around 1900 is really what brought the City of Twin Falls to life,” said Brian Olmstead, general manager of the Twin Falls Canal Company. “It turned what was once a desert into the rich farmland that it is now.” The implementation of the Milner Dam and the subsequent canal system were an early result of the Carey Act of 1894. Also known as the Federal Desert Land Act, the act promoted cooperative ventures with private companies to establish irrigation systems that would allow large areas of semi-arid federal land to become agriculturally productive. The Milner Dam project provided water to nearly 200,000 acres on the south side of the Snake River. “The initial setup included irrigation shares and ditches that flowed to nearly every lot in town until about the 1960s,” Olmstead said.