Imperial Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The YOUTH's INSTRUCTOR

The YOUTH'S INSTRUCTOR Vol. LXVII November 25, 1919 No. 47 .1 II It 10 111 • 111 =1:1=0=3n11$11211 Photo, Keystone View (o., N. Y. SUGAR LOAF MOUNTAIN, RIO DE JANEIRO, RRAZIL One of the Highest Points of South America 111.11111.1 In the New York " Sun " of April 13, 1844, there From Here and There appeared what purported to be the circumstantial account of an actual trip that had just been made by In Norway married couples may travel on the rail- an English balloon across the Atlantic from Wales to ways for a fare and a half. South Carolina. That was just before the telegraph was introduced, and mail was slow. It was therefore Adelina Patti, the world's prima donna, died re- several days before the astonished world found that cently at the age of seventy-six. it had been faked by the biggest hoax ton record. The Sun called its correspondent by the name of For- syth, but Edgar Allan Poe was the author of the Rudyard Kipling was named, we are told, for Lake story. The Sun recently spoke of the hoax which Poe Rudyard in North Staffordshire in his native land. played, with its connivance, and said : " Poe's account It was there that Lockwood Kipling, the poet's father, now becomes a statement of almost exact fact, the met Miss Macdonald, who later became his wife. In only difference of importance being that while Poe's commemoration of that meeting and the beginning flying ship took a little more than three days for its of their romance they named their son for the beauti- voyage, the British dirigible R-34 used four and one- ful sheet of water. -

The Thirty-Nine Steps 4 5 by John Buchan 6

Penguin Readers Factsheets level E Teacher’s notes 1 2 3 The Thirty-nine Steps 4 5 by John Buchan 6 SUMMARY PRE-INTERMEDIATE ondon, May 1914. Europe is close to war. Spies are he was out of action, he began to write his first ‘shocker’, L everywhere. Richard Hannay has just arrived in as he called it: a story combining personal and political London from Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in Africa to dramas. This book was The Thirty-nine Steps, published start a new life. One evening a man appears at his door in 1915. The novel marked a turning point in Buchan’s and asks for help. His name is Scudder and he is a literary career and introduced his famous adventuring THE THIRTY-NINE STEPS freelance spy, working alone. He has uncovered a German hero, Richard Hannay. The story was a great success with plot to murder the Greek Prime Minister in London and to the men in the First World War trenches. One soldier wrote steal the British plans for the outbreak of war. He is on the to Buchan, ‘The story is greatly appreciated in the midst trail of a ring of German spies, called the Black Stone. of mud and rain and shells, and all that could make trench Hannay takes Scudder into his house and learns his life depressing.’ secrets. German spies are in the street outside, watching Buchan continued to work for the intelligence services the house. during and after the war and Richard Hannay continued A few days later, Hannay returns to his flat after dinner his adventures in Greenmantle and other stories. -

Battle Management Language: History, Employment and NATO Technical Activities

Battle Management Language: History, Employment and NATO Technical Activities Mr. Kevin Galvin Quintec Mountbatten House, Basing View, Basingstoke Hampshire, RG21 4HJ UNITED KINGDOM [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is one of a coordinated set prepared for a NATO Modelling and Simulation Group Lecture Series in Command and Control – Simulation Interoperability (C2SIM). This paper provides an introduction to the concept and historical use and employment of Battle Management Language as they have developed, and the technical activities that were started to achieve interoperability between digitised command and control and simulation systems. 1.0 INTRODUCTION This paper provides a background to the historical employment and implementation of Battle Management Languages (BML) and the challenges that face the military forces today as they deploy digitised C2 systems and have increasingly used simulation tools to both stimulate the training of commanders and their staffs at all echelons of command. The specific areas covered within this section include the following: • The current problem space. • Historical background to the development and employment of Battle Management Languages (BML) as technology evolved to communicate within military organisations. • The challenges that NATO and nations face in C2SIM interoperation. • Strategy and Policy Statements on interoperability between C2 and simulation systems. • NATO technical activities that have been instigated to examine C2Sim interoperation. 2.0 CURRENT PROBLEM SPACE “Linking sensors, decision makers and weapon systems so that information can be translated into synchronised and overwhelming military effect at optimum tempo” (Lt Gen Sir Robert Fulton, Deputy Chief of Defence Staff, 29th May 2002) Although General Fulton made that statement in 2002 at a time when the concept of network enabled operations was being formulated by the UK and within other nations, the requirement remains extant. -

To What Extent Was World War Two the Catalyst Or Cause of British Decolonisation?

To what extent was World War Two the catalyst or cause of British Decolonisation? Centre Number: FR042 Word Count: 3992 Words Did Britain and her colonies truly stand united for “Faith, King and Empire” in 1920, and to what extent was Second World War responsible for the collapse of this vast empire? Cover Picture: K.C. Byrde (1920). Empire of the Sun [online]. Available at: http://worldwararmageddon.blogspot.com/2010/09/empire-of-sun.html Last accessed: 27th January 2012 Table of Contents Abstract Page 2 Introduction Page 3 Investigation Page 4 – Page 12 • The War Caused Decolonisation in Page 4 – Page 7 African Colonies • The War acted as a Catalyst in an Page 7 – Page 8 international shift against Imperialism • The War Slowed down Decolonisation in Page 8 – Page 10 Malaya • The War Acted as a Catalyst with regard Page 10 – Page 11 to India • The Method of British Imperialism was Page 11 – Page 12 condemned to fail from the start. Conclusion Page 13 Bibliography Page 14 – Page 15 1 Abstract This question answered in this extended essay is “Was World War Two the catalyst or the cause of British Decolonisation.” This is achieved by analysing how the war ultimately affected the British Empire. The British presence in Africa is examined, and the motives behind African decolonisation can be attributed directly to the War. In areas such as India, once called the ‘Jewel of the British Empire,’ it’s movement towards independence had occurred decades before the outbreak of the War, which there acted merely as a Catalyst in this instance. -

Alfred Hitchcock's the 39 STEPS

Alfred Hitchcock's THE 39 STEPS Play Guide Arizona Theatre Company Play Guide 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Alfred Hitchcock's THE 39 STEPS 3 WHO WE ARE 19 COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE AND LAZZI 21 PASTICHE CONTENTS 4 INTRODUCTION TO THE PLAY 4 SYNOPSIS 21 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES 5 THE CHARACTERS 6 JOHN BUCHAN 7 ALFRED HITCHCOCK 8 HOW ALFRED HITCHCOCK'S THE 39 STEPS CAME TO BE 10 RICHARD HANNAY – THE JAMES BOND OF HIS DAY 11 LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION 12 BRITAIN IN 1935 13 BRITISH DIALECTS 15 HISTORY OF FARCE It is Arizona Theatre Company’s goal to share the enriching experience of live theatre. This play guide is intended to help you prepare for your visit to Arizona Theatre Company. Should you have comments or suggestions regarding the play guide, or if you need more information about scheduling trips to see an ATC production, please feel free to contact us: Tucson: April Jackson Phoenix: Cale Epps Associate Education Manager Education Manager (520) 884-8210 ext 8506 (602) 256-6899 ext 6503 (520) 628-9129 fax (602) 256-7399 fax Alfred Hitchcock's THE 39 STEPS Play Guide compiled and written by Jennifer Bazzell, Literary Manager and Katherine Monberg, Artistic Intern. Discussion questions and activities prepared by April Jackson, Associate Education Manager and Amber Tibbitts, Education Manager. Layout by Gabriel Armijo. Support for ATC’s Education and Community Programming has been provided by: Organizations Mrs. Laura Grafman Ms. Norma Martens APS Individuals Kristie Graham Hamilton McRae Arizona Commission on the Arts Ms. Jessica L. Andrews and Mr. and Mrs. -

The Complete Richard Hannay Stories Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE COMPLETE RICHARD HANNAY STORIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Buchan,Dr. Keith Carabine | 992 pages | 05 Jul 2010 | Wordsworth Editions Ltd | 9781840226553 | English | Herts, United Kingdom The Complete Richard Hannay Stories PDF Book Valdemar Haraldsen is in trouble. Reading this was a bit like eating pancakes for lunch, they are filling, tasty with toppings, but don't give you much nutrition and you end up feeling hungry soon after, and wishing you'd eaten a BLT instead. The story suffers from exaggerated descriptions of its characters. The man appears to know of an anarchist plot to destabilise Europe, beginning with a plan to assassinate the Greek Premier, Constantine Karolides, during his forthcoming visit to London. On returning to Britain, Buchan built a successful career in publishing with Nelsons and Reuters. For instance, the kidnapper, Medina, is not just a good shot, he's the best shot in England next to the King. Sort order. Mr Standfast set in the later years of World War I. Greenmantle is the second of five novels by Buchan. The first remains the best, but the others, especially Greenmantle and Mr Standfast both war novels , are good too. This collection will go on my shelves with my complete Dashiell Hammett and Chandler. He is now best remembered for his adventure and spy thrillers, most notably The Thirty-Nine Steps. Availability: Available, ships in days. All Rights Reserved. This item has been added to your basket View basket Checkout. John Steinbeck. Remember me? Please sign in to write a review. Sebastian Faulks. Thanks for telling us about the problem. -

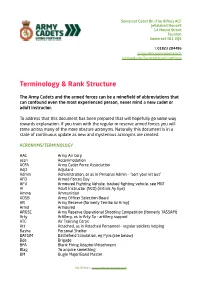

Terminology & Rank Structure

Somerset Cadet Bn (The Rifles) ACF Jellalabad HouseS 14 Mount Street Taunton Somerset TA1 3QE t: 01823 284486 armycadets.com/somersetacf/ facebook.com/SomersetArmyCadetForce Terminology & Rank Structure The Army Cadets and the armed forces can be a minefield of abbreviations that can confound even the most experienced person, never mind a new cadet or adult instructor. To address that this document has been prepared that will hopefully go some way towards explanation. If you train with the regular or reserve armed forces you will come across many of the more obscure acronyms. Naturally this document is in a state of continuous update as new and mysterious acronyms are created. ACRONYMS/TERMINOLOGY AAC Army Air Corp accn Accommodation ACFA Army Cadet Force Association Adjt Adjutant Admin Administration, or as in Personal Admin - “sort your kit out” AFD Armed Forces Day AFV Armoured Fighting Vehicle, tracked fighting vehicle, see MBT AI Adult Instructor (NCO) (initials Ay Eye) Ammo Ammunition AOSB Army Officer Selection Board AR Army Reserve (formerly Territorial Army) Armd Armoured AROSC Army Reserve Operational Shooting Competition (formerly TASSAM) Arty Artillery, as in Arty Sp - artillery support ATC Air Training Corps Att Attached, as in Attached Personnel - regular soldiers helping Basha Personal Shelter BATSIM Battlefield Simulation, eg Pyro (see below) Bde Brigade BFA Blank Firing Adaptor/Attachment Blag To acquire something BM Bugle Major/Band Master 20170304U - armycadets.com/somersetacf Bn Battalion Bootneck A Royal Marines Commando -

Wire August 2013

THE wire August 2013 www.royalsignals.mod.uk The Magazine of The Royal Corps of Signals HONOURS AND AWARDS We congratulate the following Royal Signals personnel who have been granted state honours by Her Majesty The Queen in her annual Birthday Honours List: Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) Maj CN Cooper Maj RJ Craig Lt Col MS Dooley Maj SJ Perrett Queen’s Volunteer Reserves Medal (QVRM) Lt Col JA Allan, TD Meritorious Service Medal WO1 MP Clish WO1 PD Hounsell WO2 SV Reynolds WO2 PM Robins AUGUST 2013 Vol. 67 No: 4 The Magazine of the Royal Corps of Signals Established in 1920 Find us on The Wire Published bi-monthly Annual subscription £12.00 plus postage Editor: Mr Keith Pritchard Editor Deputy Editor: Ms J Burke Mr Keith Pritchard Tel: 01258 482817 All correspondence and material for publication in The Wire should be addressed to: The Wire, RHQ Royal Signals, Blandford Camp, Blandford Forum, Dorset, DT11 8RH Email: [email protected] Contributors Deadline for The Wire : 15th February for publication in the April. 15th April for publication in the June. 15th June for publication in the August. 15th August for publication in the October. 15th October for publication in the December. Accounts / Subscriptions 10th December for publication in the February. Mrs Jess Lawson To see The Wire on line or to refer to Guidelines for Contributors, go to: Tel: 01258 482087 http://www.army.mod.uk/signals/25070.aspx Subscribers All enquiries regarding subscriptions and changes of address of The Wire should be made to: 01258 482087 or 94371 2087 (mil) or [email protected]. -

Year in Review for Dealers

Year in Review For Dealers Anthropology…………………........ 1 Guidance & Counseling…… 28 Area Studies……………………….. 2 Health……………………… 28 Art & Architecture…………………... 7 History…………………….. 31 Biology……………………………... 13 Mathematics……………….. 36 Business & Economics……………… 15 Music & Dance……………... 37 Careers & Job Search……………… 18 Philosophy & Religion…….. 37 Communication…………………..... 18 Physical Science…………… 38 Criminal Justice…………………..... 19 Political Science……………. 39 Earth Science……………………...... 20 Psychology………………… 41 Education………………………….. 21 Sociology…………………... 43 Engineering…………….…….......... 22 Sports & Fitness…………….. 46 English & Language Arts………...... 24 Technical Education……….. 46 Environmental Science…………...... 24 Technology & Society………. 46 Family & Consumer Sciences……… 27 World Languages…………... 49 Free Preview Clips Online! www.films.com/dealers T: (800) 257-5126, x4270 • F: (212) 564-1332 Anthropology 8th Fire Item # 58430 The Himbas are Shooting Subject: Anthropology This is a provocative, high-energy journey Item # 54408 through Aboriginal country showing why we Subject: Anthropology need to fix Canada's 500-year-old relationship with Indigenous In Namibia, a group of Himbas men and peoples—a relationship mired in colonialism, conflict, and denial. women of all ages have decided to make a film (4 parts, 180 minutes) showing who they are and what their life is like: incorporating key © 2012 • $679.80 • ISBN: 978-0-81608-535-4 moments in their history, daily life, ceremonies, and ancestral ties, Indigenous In the City: 8th Fire the attractions -

John Buchan Wrote the Thirty-Nine Steps While He Was Ill in Bed with a Duodenal Ulcer, an Illness Which Remained with Him All His Life

John Buchan wrote The Thirty-Nine Steps while he was ill in bed with a duodenal ulcer, an illness which remained with him all his life. The novel was his first ‘shocker’, as he called it — a story combining personal and political dramas. The novel marked a turning point in Buchan's literary career and introduced his famous adventuring hero, Richard Hannay. He described a ‘shocker’ as an adventure where the events in the story are unlikely and the reader is only just able to believe that they really happened. The Thirty-Nine Steps is one of the earliest examples of the 'man-on-the-run' thriller archetype subsequently adopted by Hollywood as an often-used plot device. In The Thirty-Nine Steps, Buchan holds up Richard Hannay as an example to his readers of an ordinary man who puts his country’s interests before his own safety. The story was a great success with the men in the First World War trenches. One soldier wrote to Buchan, "The story is greatly appreciated in the midst of mud and rain and shells, and all that could make trench life depressing." Richard Hannay continued his adventures in four subsequent books. Two were set during the war when Hannay continued his undercover work against the Germans and their allies The Turks in Greenmantle and Mr Standfast. The other two stories, The Three Hostages and The Island of Sheep were set in the post war period when Hannay's opponents were criminal gangs. There have been several film versions of the book; all depart substantially from the text, for example, by introducing a love interest absent from the original novel. -

39 Steps' a Madcap Evening of Fun (D&C)

Review: Geva's '39 Steps' a madcap evening of fun (D&C) Hitchcock presents: a madcap "Good evening" of farce in Geva's production based on the legendary filmmaker's 1935 thriller, The 39 Steps. In this Monty Python-like spoof adapted by Patrick Barlow from the John Buchan novel, dashing 37-year-old Richard Hannay is an everyman drawn into an elaborate web of intrigue. In London, he meets a World War II female spy with a thick German accent. She alludes to a conspiracy plot to steal vital British military secrets and invites herself to his apartment after they meet during a music hall performance of the human encyclopedia savant Mr. Memory. When she staggers to his side the next morning with a knife in her back, Hannay goes on the lam to escape being framed for her murder. With sly references to Hitch's most famous films, the unwitting hero must dodge murderous thugs, escape from a moving train, leap from a railway bridge, rove wearily across the Scottish moors, run from police, hounds, Birds and aircraft going North by Northwest and exit through a Rear Window. Along the way, he meets two femmes fatales, including one who suffers fromVertigo, who add spark to his love life. The cast of four actors, under the tight direction of Sean Daniels, manage to create more than 150 characters — from farmers, hotel owners and police officers to the maid who delivers the epic silent scream that turns into a train whistle. While the inventive rolling props and Houdini-like trunks by scenic designer Michael Raiford double as hotels, kitchens and bedrooms, the sound effects by Matt Callahan add lively momentum to augment each scene. -

A Study Companion

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents A Study Companion 1118 Clearview Pkwy, Metairie, LA 70001 Ph 504.885.2000 Fx 504.885.3437 [email protected] www.jpas.org 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TEACHERS’ NOTES……………………………………………………….3 LOUISIANA CONTENT STANDARDS………………………………….4 Jungle Book, THE BOOK……………………………………………….…….5 Rudyard Kipling, THE AUTHOR………………………………………….27 KIPLING’S INFLUDENCE ON CULTURE…………………………………....36 The Jungle Book, THE FILMS………………………………………………….…42 The Jungle Book, THE PLAY……………………………………………………...52 LESSONS………………………………………………………………………….55 RESOURCE LIST…………………………………………………………………….106 2 TEACHERS’ NOTES JPAS Theatre Kids! take the stage once more in another classic Disney tale brought to life through song and dance on stage! Performed by an all-kid cast, the jungle is jumpin' with jazz is this exciting Disney classic! Join Mowgli, Baloo, King Louie and the gang as they swing their way through madcap adventures and thwart the ferocious tiger, Shere Khan. With colorful characters and that toe-tapping jungle rhythm, The Jungle Book KIDS is a crowd-pleaser for audiences of all ages! Music by Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman and Terry Gilkyson Lyrics by Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman and Terry Gilkyson Additional lyrics by Marcy Heisler Book adapted by Marcy Heisler Music adapted by Bryan Louiselle Music arranged by Bryan Louiselle This Study Companion provides background information on Rudyard Kipling’s book, published in 1894, biographical information on Kipling, background information on the Disney films and play and lesson plans that pull directly from the book, films and play. One focus of the lesson plans is to highlight how an author’s individual voice can shape the telling and re-telling of a tale.