Remagnetization in the Tennessee Salient, Southern Appalachians, USA: Constraints on the Timing of Deformation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

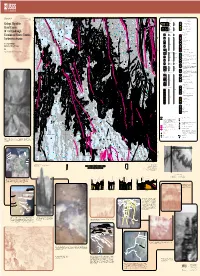

Mapping Potential Geologic Hazards for Proposed Highway Construction Projects in Pennsylvania: Route 15 in Lycoming County

Mapping Potential Geologic Hazards for Proposed Highway Construction Projects in Pennsylvania: Route 15 in Lycoming County By Stuart O. Reese, P.G. Pennsylvania Geological Survey 3240 Schoolhouse Road Middletown, PA 17057 Telephone: (717) 702-2028 Fax: (717) 702-2065 email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION acidic drainage from uncovered Marcellus Shale (a black shale with approximately 3 percent sulfur) that had to be mitigated. The current project is situated in north-central Pennsyl- Recently, the Pennsylvania Geological Survey has vania in the Deep Valleys section of the Appalachian Plateaus worked on behalf of the Pennsylvania Department of Trans- portation (PennDOT) to develop maps for specific highway physiographic province in Lycoming County, Pennsylvania. construction projects. The purpose of these maps is to identify Section C41 of U.S. Route 15 is located from north of Trout potential geologic hazards such as landslides, sinkholes, min- Run to the Village of Buttonwood in the “Steam Valley” eralization, historic deep mines, acid drainage, and ground- area of Cogan House and Lewis Townships. The improved water conditions. Map layers have included aerial imagery, highway corridor will become part of Interstate 99, the Appa- digital elevation model (DEM) datasets, digital raster graphics lachian Thruway. This requires an upgrade of the 4 1/2 mile (DRGs), bedrock units and their contacts, surficial and struc- Steam Valley section (C41) to a four-lane limited access high- tural geology features, mapped landslides, glacial boundaries, way that meets current design standards comparable to adja- and water well locations. Possible issues are described in cent sections of U.S. 15. Construction is estimated to begin in the accompanying poster for the proposed construction zones fall 2007 (pending the availability of funds). -

Chapter 2 Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

CHAPTER 2 PALEOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THE GRAND CANYON PAIGE KERCHER INTRODUCTION The Paleozoic Era of the Phanerozoic Eon is defined as the time between 542 and 251 million years before the present (ICS 2010). The Paleozoic Era began with the evolution of most major animal phyla present today, sparked by the novel adaptation of skeletal hard parts. Organisms continued to diversify throughout the Paleozoic into increasingly adaptive and complex life forms, including the first vertebrates, terrestrial plants and animals, forests and seed plants, reptiles, and flying insects. Vast coal swamps covered much of mid- to low-latitude continental environments in the late Paleozoic as the supercontinent Pangaea began to amalgamate. The hardiest taxa survived the multiple global glaciations and mass extinctions that have come to define major time boundaries of this era. Paleozoic North America existed primarily at mid to low latitudes and experienced multiple major orogenies and continental collisions. For much of the Paleozoic, North America’s southwestern margin ran through Nevada and Arizona – California did not yet exist (Appendix B). The flat-lying Paleozoic rocks of the Grand Canyon, though incomplete, form a record of a continental margin repeatedly inundated and vacated by shallow seas (Appendix A). IMPORTANT STRATIGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES AND CONCEPTS • Principle of Original Horizontality – In most cases, depositional processes produce flat-lying sedimentary layers. Notable exceptions include blanketing ash sheets, and cross-stratification developed on sloped surfaces. • Principle of Superposition – In an undisturbed sequence, older strata lie below younger strata; a package of sedimentary layers youngs upward. • Principle of Lateral Continuity – A layer of sediment extends laterally in all directions until it naturally pinches out or abuts the walls of its confining basin. -

Marine Invertebrate Assemblages from the Late Pennsylvanian (Virgilian) Holder Formation, Dry Canyon, Sacramento Mountains, South-Central New Mexico

Marine invertebrate assemblages from the Late Pennsylvanian (Virgilian) Holder Formation, Dry Canyon, Sacramento Mountains, south-central New Mexico Barry S. Kues, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, MSC03 2040, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001 Abstract Retispira–Polidevcia assemblage suggest Introduction abnormal marine conditions. The taxonomic The Holder Formation along Dry Canyon composition and relative abundances of taxa The Holder Formation, which crops out consists of a cyclic succession of Virgilian in this assemblage are unique in the Penn- along the western slopes of the Sacramen- marine siliciclastics, marine carbonates, and sylvanian of New Mexico and possibly of to Mountains, is one of the most intensive- nonmarine siliciclastics, including a large North America. The second assemblage, ly studied Pennsylvanian sedimentary basal algal bioherm complex, deposited on a from a transgressive interval of interbedded units in New Mexico. The formation was narrow shelf just west of the shoreline of the dark-gray shale and thin limestone 15–20 m Pedernal land mass. Holder marine inverte- (49–66 ft) above the first assemblage, consists named by Pray (1961) for essentially the brates have been little studied; here two of 100+ species from a wide assortment of Virgilian part of Thompson’s (1942) type quite different middle Virgilian assemblages marine groups, including gastropods (40+ Fresnal Group; the cyclic nature of Holder from an 80-m-thick (262-ft-thick) section species), brachiopods (24 species), bivalves strata was recognized by Cline (1959) and along US–82 are discussed. The first assem- (18 species), scaphopods, nautiloids, has been studied and related to correlative blage, from a 1-m-thick (3-ft-thick) dark-gray ammonoids, fusulinids, sponges, rugose basinal strata to the west (e.g., Wilson calcareous mudstone within a regressive corals, bryozoans, crinoids, echinoids, trilo- 1967); and its facies architecture and interval approximately 50 m (164 ft) above bites, ostracods, and fish teeth. -

The Lower Permian Abo Formation in the Fra Cristobal and Caballo Mountains, Sierra County, New Mexico Spencer G

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/63 The Lower Permian Abo Formation in the Fra Cristobal and Caballo Mountains, Sierra County, New Mexico Spencer G. Lucas, Karl Krainer, Dan S. Chaney, William A. DiMichele, Sebastian Voigt, David S. Berman, and Amy C. Henrici, 2012, pp. 345-376 in: Geology of the Warm Springs Region, Lucas, Spencer G.; McLemore, Virginia T.; Lueth, Virgil W.; Spielmann, Justin A.; Krainer, Karl, New Mexico Geological Society 63rd Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 580 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 2012 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. -

A2 and B2: Upper Devonian Kellwasser Extinction Events in New York and Pennsylvania: Offshore to Onshore Transect Across the F

A2 AND B2: UPPER DEVONIAN KELLWASSER EXTINCTION EVENTS IN NEW YORK AND PENNSYLVANIA: OFFSHORE TO ONSHORE TRANSECT ACROSS THE FRASNIAN-FAMENNIAN BOUNDARY ON THE EASTERN MARGIN OF THE APPALACHIAN BASIN ANDREW M. BUSH AND J. ANDREW BEARD Geosciences & Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269 GORDON BAIRD Department of Geosciences, SUNY Fredonia, Fredonia, NY 14063 D. JEFFREY OVER Department of Geological Sciences, SUNY Geneseo, Geneseo, NY 14454 with contributions by KATHERINE TUSKES Department of Geological Sciences, Atmospheric, Ocean, and Earth Science, George Mason University, Manassas, VA 20110 SARAH K. BRISSON AND JALEIGH Q. PIER Geosciences & Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269 INTRODUCTION Earth-system perturbations caused a series of mass extinction events during the Devonian Period, including the Taghanic event in the Givetian, the Lower and Upper Kellwasser events in the Frasnian, and the Hangenberg event in the Famennian (House, 2002; Bambach, 2006). These extinctions occurred against the backdrop of orbitally forced sea-level fluctuations, the Acadian Orogeny (Averbuch et al., 2005), the expansion of plants and animals on land (Algeo et al., 1995), and ecological changes in the marine biosphere (Signor and Brett, 1984; Bambach, 1999). The Frasnian-Famennian boundary in particular represents a significant global crisis, considered one of the “big five” mass extinctions (Raup and Sepkoski, 1982) that led to the demise of the widespread and diverse Devonian -

West Texas Geological Society Publications and Contents Purchase from West Texas Geological Society

West Texas Geological Society Publications and Contents Purchase from West Texas Geological Society: http://www.wtgs.org/ 77-68 Geology of the Sacramento Mountains Otero County, New Mexico Regional Distribution of Phylloid Algal Mounds in Late Pennsylvanian and Wolfcampian Strata of Southern New Mexico James Lee Wilson Growth History of a Late Pennsylvanian Phylloid Algal Organic Buildup, Northern Sacramento Mains, New Mexico D.F. Toomey, J.L. Wilson, R. Rezak Paleoecological Evidence on the Origin of the Dry Canyon Pennsylvanian Bioherms James M. Parks Biohermal Submarine Cements, Laborcita Formation (Permian), Northern Sacramento Mountains, New Mexico John M. Cys and S.J. Mazzullo Carbonate and Siliciclastic Facies of the Gobbler Formation John C. Van Wagoner The Rancheria Formation: Mississippian Intracratonic Basinal Limestones Donald A. Yurewicz Stratigraphic and Structural Features of the Sacramento Mountain Escarpment, New Mexico Lloyd C. Pray Conglomeratic Lithofacies of the Laborcita and Abo Formations ( Wolfcampian), North Central Sacramento Mountains: Sedimentology and Tectonic Importance David J. Delgado Paleocaliche Textures from Wolfcampian Strata of the Sacramento Mountains, New Mexico David J. Delgado Introduction to Road Logs Lloyd C. Pray Alamogordo to Alamo Canyon and the Western Sacramento Mountains Escarpment Field Guide and Road Log “A” Lloyd C. Pray Supplemental Field Guide to Southernmost Sacramento Mountains Escarpment – Agua Chiquita and Nigger Ed Canyons Lloyd C. Pray Alamogordo to Indian Wells Reentrant Field Guide and Road Log “B” Lloyd C. Pray Guide Locality B-1-West End of Horse Ridge John C. Van Wagoner 1 Field Guide and Road Log “C” Lloyd C. Pray Plate Shaped Calcareous Algae in Late Paleozoic Rocks of Midcontinent (abstract): James M. -

Grand Canyon

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

USGS General Information Product

Geologic Field Photograph Map of the Grand Canyon Region, 1967–2010 General Information Product 189 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Billingsley, G.H., Goodwin, G., Nagorsen, S.E., Erdman, M.E., and Sherba, J.T., 2019, Geologic field photograph map of the Grand Canyon region, 1967–2010: U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 189, 11 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/gip189. ISSN 2332-354X (online) Cover. Image EF69 of the photograph collection showing the view from the Tonto Trail (foreground) toward Indian Gardens (greenery), Bright Angel Fault, and Bright Angel Trail, which leads up to the south rim at Grand Canyon Village. Fault offset is down to the east (left) about 200 feet at the rim. -

Chapter 9. Paleozoic Vertebrate Ichnology of Grand Canyon National Park

Chapter 9. Paleozoic Vertebrate Ichnology of Grand Canyon National Park By Lorenzo Marchetti1, Heitor Francischini2, Spencer G. Lucas3, Sebastian Voigt1, Adrian P. Hunt4, and Vincent L. Santucci5 1Urweltmuseum GEOSKOP / Burg Lichtenberg (Pfalz) Burgstraße 19 D-66871 Thallichtenberg, Germany 2Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) Laboratório de Paleontologia de Vertebrados and Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geociências, Instituto de Geociências Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 3New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science 1801 Mountain Road N.W. Albuquerque, New Mexico, 87104 4Flying Heritage and Combat Armor Museum 3407 109th St SW Everett, Washington 98204 5National Park Service Geologic Resources Division 1849 “C” Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20240 Introduction Vertebrate tracks are the only fossils of terrestrial vertebrates known from Paleozoic strata of Grand Canyon National Park (GRCA), therefore they are of great importance for the reconstruction of the extinct faunas of this area. For more than 100 years, the upper Paleozoic strata of the Grand Canyon yielded a noteworthy vertebrate track collection, in terms of abundance, completeness and quality of preservation. These are key requirements for a classification of tracks through ichnotaxonomy. This chapter proposes a complete ichnotaxonomic revision of the track collections from GRCA and is also based on a large amount of new material. These Paleozoic tracks were produced by different tetrapod groups, such as eureptiles, parareptiles, synapsids and anamniotes, and their size ranges from 0.5 to 20 cm (0.2 to 7.9 in) footprint length. As the result of the irreversibility of the evolutionary process, they provide useful information about faunal composition, faunal events, paleobiogeographic distribution and biostratigraphy. -

Methane in Pennsylvania Water Wells Unrelated to Marcellus Shale Fracturing Lisa J

Methane in Pennsylvania water wells unrelated to Marcellus shale fracturing Lisa J. Molofsky of existing gas wells. The correlation of methane concentra- John A. Connor tions with elevation indicates that, on a regional level, elevat- Shahla K. Farhat ed methane concentrations in groundwater are a function of GSI Environmental Inc. geologic features, rather than shale gas development. Houston Technical literature and historical publications confirm the presence of methane gas in natural seeps and water wells Albert S. Wylie Jr. in this region for many decades, long before shale gas drill- Tom Wagner ing operations were initiated in 2006. Cabot Oil & Gas Corp. Potential sources of this naturally occurring methane in- Pittsburgh clude thermogenic gas-charged sandstones in the Catskill formation, which are tapped by most water wells in this re- Results from more than 1,700 water wells sampled and test- gion. These sandstones exhibit an extensive network of frac- ed prior to proposed gas drilling in Susquehanna County, tures, joints, and faults that serve as principle conduits of Pa., show methane to be ubiquitous in shallow groundwater, groundwater flow and potential pathways for the movement with a clear correlation of methane concentrations with sur- of shallow-sourced dissolved methane. face topography. Biogenic methane, which is produced by the natural de- Specifically, water wells located in lowland valley areas composition of organic material within thick valley alluvium exhibit significantly higher dissolved methane levels than and glacial drift deposits in the area, may also be found in wa- water wells in upland areas, with no relation to proximity ter wells that draw water from shallower sediment deposits. -

(Middle Pennsylvanian Lower Ismay Sequence), Paradox Basin, Utah

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2013-12-09 Digital Outcrop Model and Paleoecology of the Eight-Foot Rapid Algal Field (Middle Pennsylvanian Lower Ismay Sequence), Paradox Basin, Utah Colton Lynn Goodrich Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Goodrich, Colton Lynn, "Digital Outcrop Model and Paleoecology of the Eight-Foot Rapid Algal Field (Middle Pennsylvanian Lower Ismay Sequence), Paradox Basin, Utah" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 3830. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3830 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Digital Outcrop Model and Paleoecology of the Eight-Foot Rapid Algal Field (Middle Pennsylvanian Lower Ismay Sequence), Paradox Basin, Utah Colton Goodrich A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Scott Ritter, Chair John McBride Thomas Morris Department of Geology Brigham Young University December 2013 Copyright ©2013 Colton Goodrich All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Digital Outcrop Model and Paleoecology of the Eight-Foot Rapid Algal Field (Middle Pennsylvanian Lower Ismay Sequence), Paradox Basin, Utah Colton Goodrich Department of Geology, BYU Master of Science Although phylloid algal mounds have been studied for 50 year, much remains to be determined concerning the ecology and sedimentology of these Late Paleozoic carbonate buildups. Herein we perform a digital outcrop study of the well-known Middle Pennsylvanian Lower Ismay mound interval in the Paradox Basin because outcropping mounds along the San Juan River are cited as outcrop analogs of reservoir carbonates in the Paradox Basin oil province of Utah and adjacent states. -

Brenda L. Kirkland Department of Geosciences Mississippi State

9/29/15 Brenda L. Kirkland Department of Geosciences (662) 268-1032 ext. 228 (dept.) Mississippi State University (662) 341-8998 (cell) Mississippi State, MS 39762 [email protected] Education Louisiana State University Ph.D. Geology (Botany minor) 1992 Texas A&M University M.S. Geology 1986 Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität 1982-83 Course work in geology 1983 (Munich, Germany) The University of Texas at Austin B.S. Geology (Botany minor) 1982 B.A. German (Spanish minor) 1980 Significant Accomplishments • Published 34 papers (26 peer-reviewed), 3 guidebooks, and 3 books • Awarded $5,210,766 in grants • Supervised 28 Master’s and 6 Ph.D. candidates • Developed and taught 21 different courses for classroom, field, and on-line Professional Experience Associate Professor, Mississippi State University, 2010-Present On campus courses taught: • Geomorphology (Fall 2015) • Geowriting (Fall 2010, 2011) • Honors Seminar: Food Security (Spring 2014) • Introduction to Environmental Geology (Spring 2010, 2011, 2012) • Introduction to Earth Science I (Physical Geology) (Fall 2011, Maymester 2013, 2014, 2015) • Introduction to Earth Science II (Historical Geology) (Fall 2014) • Mineralogy (Fall 2012) • Philosophy and Ethics (Spring 2016) • Sedimentology I (Spring 2011, 2013, Fall 2015) • Structural Geology (Spring 2010, 2012, 2013, 2914, 2015, 2016) • Special Topic in Geology: Carbonate Petrology (Spring 2011, Fall 2014) • Special Topic in Geology: Participation in Research (Maymester 2010, 2011, 2012) • Special Topic in Geology: Imperial Barrel Competition