Doc Pomus 1992.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Download a Sample Song List

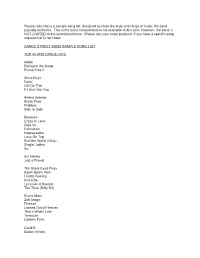

Please note this is a sample song list, designed to show the style and range of music the band typically performs. This is the most comprehensive list available at this time; however, the band is NOT LIMITED to the selections below. Please ask your event producer if you have a specific song request that is not listed. TOP 40 AND DANCE HITS Fetty Wap My Way Ariana Grande Fifth Harmony Thank You Next Work From Home Beyonce Flo Rida Love On Top Low The Black Eyed Peas G-Easy I Gotta Feeling No Limit Bruno Mars Ginuwine Finesse Pony That’s What I Like Gnarls Barkley Calvin Harris Crazy This Is What You Came For Halsey Camila Cabello Without Me Havana Icona Pop Cardi B I Love It I Like It Iggy Azalea Carly Rae Jepsen Fancy Call Me Maybe Imagine Dragons Clean Bandit Thunder Rather Be Jason Derulo Cupid Talk Dirty To Me Cupid Shuffle The Other Side Want To Want Me Daft Punk Get Lucky Jennifer Lopez Dinero David Guetta On The Floor Titanium Jeremih Demi Lovato Oui Neon Lights Jessie J Desiigner Bang Bang Panda Jidenna DNCE Classic Man Cake By The Ocean John Legend Drake Green Light God’s Plan Nice For What Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop This Feeling Echosmith Filthy Cool Kids Say Something Ellie Goulding Katy Perry Burn Dark Horse Firework Teenage Dream Kelly Clarkson Sam Smith Stronger Latch Stay With Me Kevin Gates 2 Phones T. Pain All I Do Is Win Lady Gaga Shallow Taylor Swift Delicate Lil’ Jon Shake It Off Turn Down For What Trey Songz Macklemore Bottoms Up Can’t Hold Us Usher Magic! DJ Got Us Falling In Love Rude Good Kisser Yeah Maroon 5 -

2012 Calendar of Events

2012 Calendar of Events Week 1: June 23 – 29 Week 2: June 30 – July 6 Week 3: July 7 – 13 Week 4: July 14 – 20 Week 5: July 21 – 27 All 8:15 pm programs are held in Hoover Auditorium, Lutheran Chautauqua Chaplain of the Week: The Rev. Dr. Myron McCoy, Lutheran Summer Assembly Chaplain of the Week: The Rev. Orlando Chaffee, Chaplain of the Week: Dr. Phillip Gulley, Quaker Pastor President, Saint Paul School of Theology, Kansas City, MO District Superintendent, North Coast District, East Ohio & Writer, Fairfield Friends Meeting, Avon, IN unless otherwise noted. An up-to-date listing of events Chaplain of the Week: The Rev. Dave Daubert, Chaplain of the Week: Bishop Elizabeth Eaton, CEO/Director, A Renewal Enterprise, Inc., Chicago, IL Northeastern Ohio Synod, Evangelical Lutheran Church in Conference UMC, Cleveland, OH may be found at www.lakesideohio.com/events. WEEK 2 SEMINARS America, Cuyahoga Falls, OH WEEK 5 SEMINARS WEEK 4 SEMINARS To view a complete list of educational seminars, WEEK 1 SEMINARS JULY 2-6 All Things Americana Seminars on topics related to July 23-27 The Chautauqua Movement In conjunction with the JULY 16-20 The Great Lakes Seminars related to all five Great Lakes visit www.lakesideohio.com/education. June 25-29 2012 Elections Seminars on the 2012 elections, with American history & culture WEEK 3 SEMINARS Chautauqua Network Annual Meeting, gain further insight into the history a focus on the nomination process, general elections, state/local elections July 9-13 – sponsored by Wesleyan Senior Living Ethics in Society Seminars on state, national, business & international of the Chautauqua Movement & the new Chautauqua Trail & campaign finance with Paul Beck, PhD, Distinguished Prof. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

“Amarillo by Morning” the Life and Songs of Terry Stafford 1

In the early months of 1964, on their inaugural tour of North America, the Beatles seemed to be everywhere: appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, making the front cover of Newsweek, and playing for fanatical crowds at sold out concerts in Washington, D.C. and New York City. On Billboard magazine’s April 4, 1964, Hot 100 2 list, the “Fab Four” held the top five positions. 28 One notch down at Number 6 was “Suspicion,” 29 by a virtually unknown singer from Amarillo, Texas, named Terry Stafford. The following week “Suspicion” – a song that sounded suspiciously like Elvis Presley using an alias – moved up to Number 3, wedged in between the Beatles’ “Twist and Shout” and “She Loves You.”3 The saga of how a Texas boy met the British Invasion head-on, achieving almost overnight success and a Top-10 hit, is one of triumph and “Amarillo By Morning” disappointment, a reminder of the vagaries The Life and Songs of Terry Stafford 1 that are a fact of life when pursuing a career in Joe W. Specht music. It is also the story of Stafford’s continuing development as a gifted songwriter, a fact too often overlooked when assessing his career. Terry Stafford publicity photo circa 1964. Courtesy Joe W. Specht. In the early months of 1964, on their inaugural tour of North America, the Beatles seemed to be everywhere: appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, making the front cover of Newsweek, and playing for fanatical crowds at sold out concerts in Washington, D.C. and New York City. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

Please Note This Is a Sample Song List, Designed to Show the Style and Range of Music the Band Typically Performs

Please note this is a sample song list, designed to show the style and range of music the band typically performs. This is the most comprehensive list available at this time; however, the band is NOT LIMITED to the selections below. Please ask your event producer if you have a specific song request that is not listed. DANCE STREET BAND SAMPLE SONG LIST TOP 40 AND DANCE HITS Adele Rolling in the Deep Rumor Has It Alicia Keys Fallin’ Girl On Fire If I Ain’t Got You Ariana Grande Break Free Problem Side to Side Beyonce Crazy In Love Deja Vu Formation Irreplaceable Love On Top Run the World (Girls) Single Ladies Xo Biz Markie Just a Friend The Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow I Gotta Feeling Imma Be Let’s Get It Started The Time (Dirty Bit) Bruno Mars 24K Magic Finesse Locked Out of Heaven That’s What I Like Treasure Uptown Funk Cardi B Bodak Yellow Carly Rae Jespen Call Me Maybe Calvin Harris This is What You Came For Feel So Close Cee Lo Green Forget You The Chainsmokers Closer Don't Let Me Down Chance the Rapper No Problem Chris Brown Look at Me Now Christina Perri A Thousand Years Christina Aguilera, Lil’Kim, Mya &Pink Lady Marmalade Clean Bandit Rather Be Cupid Cupid Shuffle Daft Punk Get Lucky One More Time David Guetta Titanium Demi Lovato Neon Lights Sorry Not Sorry Desiigner Panda DNCE Cake by the Ocean Drake Hold on We're Going Home Hotline Bling One Dance Echosmith Cool Kids Ed Sheeran Perfect Shape of You Thinking Out Loud Ellie Goulding Burn Fetty Wap My Way Fifth Harmony Work from Home Flo Rida Low Fun. -

The Influence of Latin Music in Postwar New York City Overview

THE INFLUENCE OF LATIN MUSIC IN POSTWAR NEW YORK CITY OVERVIEW ESSENTIAL QUESTION How did the growth of New York City’s Latino population in the 1940s and 50s help to increase the popularity of Latin music and dance in American culture? OVERVIEW In the fall of 1957, the Broadway musical West Side Story opened at the Winter Garden Theatre in Manhattan. Featuring a musical score by Leonard Bernstein and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, its story centered on two rival teenage gangs -- the all-white Jets and the Puerto Rican Sharks -- facing off on the streets of New York City. The play’s showcase number, “America,” dramatized the disparities between life in rural Puerto Rico and the opportunities available to immigrants living in the United States. Bernstein’s orchestrations drew heavily on Latin-style percussion and dance rhythms -- sounds that had become prominent in New York over the course of the 1940s and 50s, as the city’s Latino population boomed. During and immediately following World War II, the United States experienced an historic wave of immigration from Latin America, including a record number of immigrants from the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico. In 1940, the U.S. census reported just under 70,000 Puerto Ricans living in the country; by 1950, that number had grown to over 226,000, with eighty-three percent of that population living in New York City. As alluded to in West Side Story, many Puerto Ricans, (who held natural born U.S. citizenship), arrived seeking jobs in factories and on ship docks -- industries with greater economic security than the agricultural work available in Puerto Rico. -

Jet Label Discography

Jet Label Discography Jet releases in the United Artists UA-LA series UA-LA-583-G - Fastbuck - Fastbuck [1976] Under It All/The Mirror/I've Got To Be Strong/Rock & Roll Star/Understanding Is The Word/Hard on the Boulevard/Rockin' Chair Ride/Practically 5th Avenue/Come To The Country/Sometime Man UA-LA-630-G - Ole ELO - The Electric Light Orchestra [1976] 10538 Overture/Kuiama/Roll Over Beethoven//Showdown/Ma-Ma-Ma Belle/Can’tGet It Out of My Head/Boy Blue/Evil Woman/Strange Magic JT-LA-732-G - Live ‘N’Kickin’- Kingfish [1977] Good-Bye Yer Honor/Juke/Mule Skinner Blues/I Hear You Knocking/Hypnotize//Jump For Joy/Overnight Bag/Jump Back/Shake and Fingerpop/Around and Around JT-LA-790-H - Before We Were So Rudely Interrupted - The Original Animals [1977] The Last Clean Shirt (Brother Bill)/It’sAll Over Now, Baby Blue/Fire on the Sun/As The Crow Flies/Please Send Me Someone To Love//Many Rivers To Cross/Just Want A Little Bit/Riverside County/Lonely Avenue/The Fool JT-LA-809-G - Alan Price - Alan Price [1977] Rainbow’sEnd/I’ve Been Hurt/I Wanna Dance/Let Yourself Go/Just For You//I’mA Gambler/Poor Boy/The Same Love/Is It Right?/Life Is Good/The Thrill JT-LA-823 L2 - Out of the Blue - The Electric Light Orchestra [1977] Two record set. Turn To Stone/It’s Over/Sweet Talkin’Woman/Across The Border//Night in the City/Starlight/Jungle/Believe Me Now/Steppin’ Out//Standin’inthe Rain/Big Wheels/Summer and Lightning/Mr. -

Please Note This Is a Sample Song List, Designed to Show the Style and Range of Music the Band Typically Performs

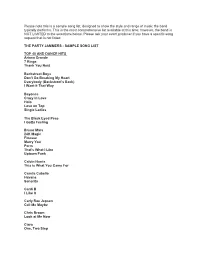

Please note this is a sample song list, designed to show the style and range of music the band typically performs. This is the most comprehensive list available at this time; however, the band is NOT LIMITED to the selections below. Please ask your event producer if you have a specific song request that is not listed. THE PARTY JAMMERS - SAMPLE SONG LIST TOP 40 AND DANCE HITS Ariana Grande 7 Rings Thank You Next Backstreet Boys Don't Go Breaking My Heart Everybody (Backstreet's Back) I Want it That Way Beyonce Crazy in Love Halo Love on Top Single Ladies The Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Bruno Mars 24K Magic Finesse Marry You Perm That's What I Like Uptown Funk Calvin Harris This is What You Came For Camila Cabello Havana Senorita Cardi B I Like It Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe Chris Brown Look at Me Now Ciara One, Two Step Clean Bandit Rather Be Cupid Cupid Shuffle Daft Punk Get Lucky David Guetta Titanium Demi Lovato Neon Lights Desiigner Panda DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide DJ Khaled All I Do is Win DNCE Cake by the Ocean Drake God's Plan Nice for What Toosie Slide Echosmith Cool Kids Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Ellie Goulding Burn Fetty Wap My Way Fifth Harmony Work from Home Flo Rida Low G-Easy No Limit Ginuwine Pony Gnarls Barkley Crazy Gwen Stefani Hollaback Girl Halsey Without Me H.E.R. Best Part Icono Pop I Love It Iggy Azalea Fancy Imagine Dragons Thunder Israel Kamakawiwoʻole Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World Jason Derulo Talk Dirty to Me The Other Side Want to Want Me Jennifer Lopez Dinero On the Floor Jeremih Oui Jessie -

Gary Burke Bill Milhizer

Art Music Culture Reception Gary Burke Troy native and renowned 18 drummer talks technique. Bill Milhizer Fleshtones drummer tells of 22 gigging in a changing scene. www.radioradiox.com Free May 2019 Page 3 Music Art Culture Revolution The Delicate Art of Surprise You can say what you want about Chandler Travis, just spell his name right. And come prepared for amazement. By Liam Sweeny for Mapanare.us, since one of the things you said was that you’d rather be booed than ignored. In ariety is the spice of life. We live in a world terms of engaging the audience and finding that bound at every turn by a category; a genre, love, however it comes, how best do you battle that Va look, a clique, a demographic – it would indifference? drive us truly nuts if there was a box we could CT: I’m a big fan of the element of surprise, and check for our specific strain of insanity. But we can that combined with a certain creative restlessness always find relief in the unique people, even as we and natural selfishness means that usually, I’m stand and point and, unbeknownst to anyone, wish most interested in surprising myself; that said, I we had their moxie. do try to make sure that whatever we do, it’s a sur- Observations Chandler Travis is a welcome respite from “va- prise. Real surprises are so rare, can’t think of a and Ramblings ........25 riety is the spice of life” and other things we sleep- better present, really; always hope it’s a pleasant walk through our minds. -

Faculty Grades Administrative Performance by RUSS WILLIAMS References to “About Right.” Leadership Quality of O’Meara

IOBSERVER Thursday, April 11, 1996 • Vol. XXVII No. 121 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY'S Panel readies for Board report By GWENDOLYN NORGLE body,” Patrick said. teaching methods. For exam Associate News Editor As the Center for Social Con ple, in one of her classes, an cerns intern on multicultural outdated 1970’s text that was The contributors to the Stu concerns, Haley said she has a “homophobic, sexist and racist ” dent Government Spring 1996 lot to offer to the report. As the was used, she said. Report to the Board of Trustees lia so n fo r th e CSC and the In addition, as the only are looking forward to the op Office for Multicultural Student African-American in many of portunity to Affairs at Notre Dame, she her classes, Haley said she feels present their works on a number of multicul- she is expected to be the personal lurally related projects. Some of “authority on all African-Amer experiences these include the Martin Luther icans around the world. ” dealing with King, Jr., Planning Committee, Silva, a representative from multicultural- the Learning to Talk About Gays and Lesbians of Notre ism at Notre Race Retreat, and the Cultural Dame and Saint Mary’s College The Observer/Alyson Frick Dame. Diversity Seminar, which is a and a member of the Ad Hoc Peri Arnold, David Leege and Samuel Best discuss the role of “self After one-week learning program fo Committee on Gay and Lesbian presentation" in Election 1996. announcing Patrick cusing on diverse ethnic neigh Student Needs, said that he also s o p h o m o r e borhoods in Chicago.