Migration, Islam and Identity Strategies in Kwazulu-Natal : Notes on the Making of Indians and Africans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BLACK ISLAM SOUTH AFRICA Religious Territoriality, Conversion

BLACK ISLAM SOUTH AFRICA Religious Territoriality, Conversion, and the Transgression of Orderly Indigeneity Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades Dr. phil. im Promotionsfach Geographie am Fachbereich Chemie, Pharmazie, Geographie und Geowissenschaften der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz vorgelegt von Matthias Gebauer geb. in Lichtenfels 2019 i Abstract Social alienation and the struggle to belong in the South African society are not only matters of political discourse but touch the practical sphere of everyday life in the respective places of residence. This thesis therefore approaches the entanglements of religion and space within the processes of re-ordering African indigeneity in post-apartheid South Africa. It asks how conversion to Islam constitutes the longing for a post-colonial and post-racialized African self. This study specifically engages with dynamics surrounding Black and Muslim practices and identity politics in formerly demarcated Black African areas. Here, even after the official end of apartheid, spatial racialization and social inequalities persist. Modes of orderings rooted in colonialism and apartheid still define what orderly belonging and African indigeneity mean. Thus, the inhabitants of those spaces find themselves in situations every day in which their habitat continuously ascribes oppression and racialization. The post-1994 promise for equal citizenship seems to be slowly fading, becoming a broken promise, on whose fulfillment the majority of people who were previously—by official definition and demarcation—only granted the right of being a migratory workforce, sojourners in the White spaces, are still waiting. Against this background, this thesis engages with the attempts to reformulate and recreate African indigeneity on the basis of a counter-hegemonic ideology of being Black and Muslim. -

Ebrahim E. I. Moosa

January 2016 Ebrahim E. I. Moosa Keough School of Global Affairs Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies University of Notre Dame 100 Hesburgh Center for International Studies, Notre Dame, Indiana, USA 46556-5677 [email protected] www.ebrahimmoosa.com Education Degrees and Diplomas 1995 Ph.D, University of Cape Town Dissertation Title: The Legal Philosophy of al-Ghazali: Law, Language and Theology in al-Mustasfa 1989 M.A. University of Cape Town Thesis Title: The Application of Muslim Personal and Family Law in South Africa: Law, Ideology and Socio-Political Implications. 1983 Post-graduate diploma (Journalism) The City University London, United Kingdom 1982 B.A. (Pass) Kanpur University Kanpur, India 1981 ‘Alimiyya Degree Darul ʿUlum Nadwatul ʿUlama Lucknow, India Professional History Fall 2014 Professor of Islamic Studies University of Notre Dame Keough School for Global Affairs 1 Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies & Department of History Co-director, Contending Modernities Previously employed at the University of Cape Town (1989-2001), Stanford University (visiting professor 1998-2001) and Duke University (2001-2014) Major Research Interests Historical Studies: law, moral philosophy, juristic theology– medieval studies, with special reference to al-Ghazali; Qur’anic exegesis and hermeneutics Muslim Intellectual Traditions of South Asia: Madrasas of India and Pakistan; intellectual trends in Deoband school Muslim Ethics medical ethics and bioethics, Muslim family law, Islam and constitutional law; modern Islamic law Critical Thought: law and identity; religion and modernity, with special attention to human rights and pluralism Minor Research Interests history of religions; sociology of knowledge; philosophy of religion Publications Monographs Published Books What is a Madrasa? University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015): 290. -

Historical Evolution of Durban's Public Transport System and Challenges For

Historical evolution of Durban’s public transport system Historical evolution of Durban’s public transport system and challenges for the post-apartheid metropolitan government Sultan Khan School of Social Sciences University of KwaZulu-Natal [email protected] Abstract The history of public transport in Durban is characterised by a diverse set of socio-political forces that have shaped and styled its present form. Characterised by horse and cart driven coach modes of transport in the early colonial period, Durban’s transport systems’ transition to motorised forms has been founded on racial exclusionary measures that sought to sustain white monopoly over the economic sector at the expense of under-development of the vast majority of disenfranchised Blacks in the city. In its transport history different modes of conveyance were used and it rapidly adapted to motorised transport which placed Durban in the forefront of economic prosperity. To Durban’s credit its transport sector boasts to have made a transition from exotically human drawn rickshas, to an animal drawn tram which was later superseded by electric driven trams. Durban was the first province to have introduced the railway mode of transport which served as a foundation for its economic growth. Notwithstanding these achievements, both during colonialism and apartheid the transport sector excluded the majority of the Black populace in the city and even when it did include them strict racial separation was maintained. Under apartheid transport engineering was heightened to keep racial groups apart and Durban was the first city to respond to the notorious Group Areas Act which created racial enclaves in the form of townships for the different race groups. -

Durban Reality Tour: a Collection of Material About the 'Invisible'

Durban Reality Tour A collection of material about the ‘invisible’ side of the City Llywellyn Leonard, Sufian H Bukurura & Helen Poonen (Compilers) 2008 Durban Reality Tour A collection of material about the ‘invisible’ side of the City Llywellyn Leonard, Sufian H Bukurura & Helen Poonen (Compilers) Contents Maps Durban and surrounding areas Durban Metro South Durban Industries Introduction Part I. News clips 1.1 Street Traders Traders angry over arrests (Sunday Tribune, 24 June 2004) Police battle Durban street traders (Mail & Guardian, 18 June 2007) 1.2 South Durban: Pollution and Urban Health Crisis Struggles against ‘toxic’ petrochemical industries, (B Maguranyanga, 2001) Global day of action hits SHELL & BP (SAPREF) gates (Meindert Korevaar, SDCEA Newsletter, volume 8, November 2006) Health study proves that communities in South Durban face increased health problems due to industrial pollution (Rico Euripidou, groundWork, volume 8 number 3, September 2006) Will city authorities take action to enforce Engen’s permit? (Press Release, South Durban Community Environmental Alliance, 27 January 2006) Engen violates permit conditions, (groundWork Press Release, 7 July 2005) Africa: Shell and Its Neighbours, (groundWork Press Release 24 April 2004) Pipelines to be replaced in polluted areas, (The Mercury, 03 June 2005) Homes threatened by cleanup plans (Tony Carne, The Mercury, 19 June 2006) Aging refineries under fire (Southern Star, 3 November 2006) Multinationals ‘water down South Africa’s Constitution’ (Tony Carne, The Mercury, -

Padayachee, Vishnu : an Analysis of Some Aspects of Employment And

AN ANALYSIS OF SOKE ASPECTS OF EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT IN THE AFRICAN TOWNSHIPS OF maAZI AND LAMOWnILLE - A PBELIMINAEY.INVESTIGATION Vishnu Padayachee Occasional Paper No. 14 . December 1985 ISBN No. 0-949947-75-X Institute for Social and Economic Research University of Durban-Westville Private Bag X54001 DUBBAN 4000 CONTENTS List of Tables Acknowledgements I. Introduction 2. Sampling and Fieldwork 3. General Household Data 4. Profile ot Earners: Demographic, Employment and Income Struc Cure 5. .4 Profile of the Unemployed 6. Summary and Conclusions Footnotes (ii) LlST OF TABLES Table 1 General Household Composition Table 2 Household lncome Structure and Distribution Table 3 Occupational Distribution of Earners Table 4 Length of Present Employment Table 5 Hours Worked by the Employed in the Past Week Table 6 Number of Months Worked in the Past Year Table 7 Distribution of lncome Among Earners Table 8 Distribution by Sex of the Unemployed Table 9 Age Distribution of the Unemployed Table 10 Marital Status of the Unemployed Table I1 Educational Levels of the Unemployed Table 12 Keasons for Unemployment Table 13 Duration of Unemployment Table 14 Methods of Job Search Activity Table 15 Strategies of Survival: Unemployed Persons .vpaeA p~qeqspue sTiezlueu uehg 'sTna? Lapa7 01 os~e'X~~euyj !laded syql jo Su~dXlaql alaldmos 01 aneaI iaq 30 lied dn ahet oqn 'qaTCiapuI eqxruv !yion utysap pue InoXsl InjIyys syq ioj Tienuefl Paid !asyliadxa IeuoTlexndrnos pue Buypos iyaql 103 ialuan UTM pue iapuaho3 lac '1yeN Xex !yionp~aTj aql moqe xuan Xaq~ qs~qn uy Ken luaysyjja pue syqseysnqlua aql ioj iolsoa pun asuaiax !aiyeuuo~lsanb aql 30 uo~~nlsuni~aql 103 Imosw TTaauo !tuypuw~siapun pue asuepp8 'asue~slssealqen~s-A syq ioj orepv-ia~lna uqor iossajoid -1saCoid syql q1p sXen snolieh uy an, padpq or[n slenprnypuy Buyno~~oj aql 01 uorle~~aiddeXm ssaidxa 01 ayrl pTnoqs 1 1. -

Islamic Liberation Theology in South Africa: Farid Esack’S Religio-Political Thought

ISLAMIC LIBERATION THEOLOGY IN SOUTH AFRICA: FARID ESACK’S RELIGIO-POLITICAL THOUGHT Yusuf Enes Sezgin A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Cemil Aydin Susan Dabney Pennybacker Juliane Hammer ã2020 Yusuf Enes Sezgin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Yusuf Enes Sezgin: Islamic Liberation Theology in South Africa: Farid Esack’s Religio-Political Thought (Under the direction of Cemil Aydin) In this thesis, through analyzing the religiopolitical ideas of Farid Esack, I explore the local and global historical factors that made possible the emergence of Islamic liberation theology in South Africa. The study reveals how Esack defined and improved Islamic liberation theology in the South African context, how he converged with and diverged from the mainstream transnational Muslim political thought of the time, and how he engaged with Christian liberation theology. I argue that locating Islamic liberation theology within the debate on transnational Islamism of the 1970s onwards helps to explore the often-overlooked internal diversity of contemporary Muslim political thought. Moreover, it might provide important insights into the possible continuities between the emancipatory Muslim thought of the pre-1980s and Islamic liberation theology. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to many wonderful people who have helped me to move forward on my academic journey and provided generous support along the way. I would like to thank my teachers at Boğaziçi University from whom I learned so much. I was very lucky to take two great courses from Zeynep Kadirbeyoğlu whose classrooms and mentorship profoundly improved my research skills and made possible to discover my interests at an early stage. -

Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment

Coetzee, FP HIA: Proposed Housing Upgrade of Low Income Houses in Amatikwe Phase 2 & 3, eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment: Phase 1 Investigation for the Proposed In-Situ Housing Upgrade of Approximately 3500 Low Income Houses in Amatikwe Phase 2 and Phase 3, eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal For Project Applicant Environmental Consultant eThekwini Municipality: Asande Projects Consulting & Engineering (Pty) Ltd Human Settlements Unit Rosen Office Park, No. 2 Matuka Close, 188 Anton Lembede Street, Durban Halfway House, Midrand, 1685 Tel: 031 322 7848 Tel: 011 315 6794 Fax: 031 311 3493 Fax: 011 312 3359 Contact: P. Mhlongo E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] By Francois P Coetzee Heritage Consultant ASAPA Professional Member No: 028 99 Van Deventer Road, Pierre van Ryneveld, Centurion, 0157 Tel: (012) 429 6297 Fax: (012) 429 6091 Cell: 0827077338 [email protected] Date: December 2019 Revised: January 2020 April 2020 Version: 3 (Final Report) 1 Coetzee, FP HIA: Proposed Housing Upgrade of Low Income Houses in Amatikwe Phase 2 & 3, eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal Executive Summary This report contains a comprehensive heritage impact assessment investigation in accordance with the provisions of Sections 38(1) and 38(3) of the National Heritage Resources Act (Act No. 25 of 1999) (NHRA) and focuses on the survey results from a cultural heritage survey as requested by Asande Projects Consulting and Engineering (Pty) Ltd. eThekwini Municipality: Human Settlements Unit is planning to undertake in-situ housing upgrades for low income houses in Amatikwe Phase 2 and 3. -

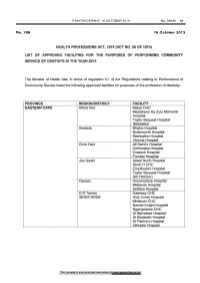

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for the Purposes of Performing Community Service by Dentists in the Year

STAATSKOERANT, 16 OKTOBER 2013 No. 36936 13 No. 788 16 October 2013 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY DENTISTS IN THE YEAR 2014 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of dentistry. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Alfred Nzo Maluti CHC Madzikane Ka Zulu Memorial Hospital Taylor Bequest Hospital (Matatiele) Amato le Bhisho Hospital Butterworth Hospital Madwaleni Hospital Victoria Hospital Chris Hani All Saint's Hospital Cofimvaba Hospital Cradock Hospital Frontier Hospital Joe Gqabi Aliwal North Hospital Block H CHC Empilisweni Hospital Taylor Bequest Hospital (Mt Fletcher) Cacadu Humansdorp Hospital Midlands Hospital Settlers Hospital O.R Tambo Gateway CHC ISRDS NODE Holy Cross Hospital Mhlakulo CHC Nessie Knight Hospital Ngangelizwe CHC St Barnabas Hospital St Elizabeth Hospital St Patrick's Hospital Zithulele Hospital This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 14 No. 36936 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 OCTOBER 2013 FREE STATE Motheo District(DC17) National Dental Clinic Botshabelo District Hospital Fezile Dabi District(DC20) Kroonstad Dental Clinic MafubefTokollo Hospital Complex Metsimaholo/Parys Hospital Complex Lejweleputswa DistrictWelkom Clinic Area(DC18) Thabo Mofutsanyana District Elizabeth Ross District Hospital* (DC19) Itemoheng Hospital* ISRDS NODE Mantsopa -

Community Struggle from Kennedy Road Jacob Bryant SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2005 Towards Delivery and Dignity: Community Struggle From Kennedy Road Jacob Bryant SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Jacob, "Towards Delivery and Dignity: Community Struggle From Kennedy Road" (2005). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 404. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/404 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWARDS DELIVERY AND DIGNITY: COMMUNITY STRUGGLE FROM KENNEDY ROAD Jacob Bryant Richard Pithouse, Center for Civil Society School for International Training South Africa: Reconciliation and Development Fall 2005 “The struggle versus apartheid has been a little bit achieved, though not yet, not in the right way. That’s why we’re still in the struggle, to make sure things are done right. We’re still on the road, we’re still grieving for something to be achieved, we’re still struggling for more.” -- Sbusiso Vincent Mzimela “The ANC said ‘a better life for all,’ but I don’t know, it’s not a better life for all, especially if you live in the shacks. We waited for the promises from 1994, up to 2004, that’s 10 years of waiting for the promises from the government. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Identity Construction in Post-apartheid South Africa: the Case of the Muslim Community Rania Hassan PhD in African Studies The University of Edinburgh 2011 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................................................................I ABSTRACT........................................................................................................................................III DECLARATION..................................................................................................................................V GLOSSARY....................................................................................................................................... -

Ward Councillors Pr Councillors Executive Committee

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE KNOW YOUR CLLR WEZIWE THUSI CLLR SIBONGISENI MKHIZE CLLR NTOKOZO SIBIYA CLLR SIPHO KAUNDA CLLR NOMPUMELELO SITHOLE Speaker, Ex Officio Chief Whip, Ex Officio Chairperson of the Community Chairperson of the Economic Chairperson of the Governance & COUNCILLORS Services Committee Development & Planning Committee Human Resources Committee 2016-2021 MXOLISI KAUNDA BELINDA SCOTT CLLR THANDUXOLO SABELO CLLR THABANI MTHETHWA CLLR YOGISWARIE CLLR NICOLE GRAHAM CLLR MDUDUZI NKOSI Mayor & Chairperson of the Deputy Mayor and Chairperson of the Chairperson of the Human Member of Executive Committee GOVENDER Member of Executive Committee Member of Executive Committee Executive Committee Finance, Security & Emergency Committee Settlements and Infrastructure Member of Executive Committee Committee WARD COUNCILLORS PR COUNCILLORS GUMEDE THEMBELANI RICHMAN MDLALOSE SEBASTIAN MLUNGISI NAIDOO JANE PILLAY KANNAGAMBA RANI MKHIZE BONGUMUSA ANTHONY NALA XOLANI KHUBONI JOSEPH SIMON MBELE ABEGAIL MAKHOSI MJADU MBANGENI BHEKISISA 078 721 6547 079 424 6376 078 154 9193 083 976 3089 078 121 5642 WARD 01 ANC 060 452 5144 WARD 23 DA 084 486 2369 WARD 45 ANC 062 165 9574 WARD 67 ANC 082 868 5871 WARD 89 IFP PR-TA PR-DA PR-IFP PR-DA Areas: Ebhobhonono, Nonoti, Msunduzi, Siweni, Ntukuso, Cato Ridge, Denge, Areas: Reservoir Hills, Palmiet, Westville SP, Areas: Lindelani C, Ezikhalini, Ntuzuma F, Ntuzuma B, Areas: Golokodo SP, Emakhazini, Izwelisha, KwaHlongwa, Emansomini Areas: Umlazi T, Malukazi SP, PR-EFF Uthweba, Ximba ALLY MOHAMMED AHMED GUMEDE ZANDILE RUTH THELMA MFUSI THULILE PATRICIA NAIR MARLAINE PILLAY PATRICK MKHIZE MAXWELL MVIKELWA MNGADI SIFISO BRAVEMAN NCAYIYANA PRUDENCE LINDIWE SNYMAN AUBREY DESMOND BRIJMOHAN SUNIL 083 7860 337 083 689 9394 060 908 7033 072 692 8963 / 083 797 9824 076 143 2814 WARD 02 ANC 073 008 6374 WARD 24 ANC 083 726 5090 WARD 46 ANC 082 7007 081 WARD 68 DA 078 130 5450 WARD 90 ANC PR-AL JAMA-AH 084 685 2762 Areas: Mgezanyoni, Imbozamo, Mgangeni, Mabedlane, St. -

History Workshop

UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND, JOHANNESBURG HISTORY WORKSHOP STRUCTURE AND EXPERIENCE IN THE MAKING OFAPARTHEID 6-10 February 1990 AUTHOR: Iain Edwards and Tim Nuttall TITLE: Seizing the moment : the January 1949 riots, proletarian populism and the structures of African urban life in Durban during the late 1940's 1 INTRODUCTION In January 1949 Durban experienced a weekend of public violence in which 142 people died and at least 1 087 were injured. Mobs of Africans rampaged through areas within the city attacking Indians and looting and destroying Indian-owned property. During the conflict 87 Africans, SO Indians, one white and four 'unidentified' people died. One factory, 58 stores and 247 dwellings were destroyed; two factories, 652 stores and 1 285 dwellings were damaged.1 What caused the violence? Why did it take an apparently racial form? What was the role of the state? There were those who made political mileage from the riots. Others grappled with the tragedy. The government commission of enquiry appointed to examine the causes of the violence concluded that there had been 'race riots'. A contradictory argument was made. The riots arose from primordial antagonism between Africans and Indians. Yet the state could not bear responsibility as the outbreak of the riots was 'unforeseen.' It was believed that a neutral state had intervened to restore control and keep the combatants apart.2 The apartheid state drew ideological ammunition from the riots. The 1950 Group Areas Act, in particular, was justified as necessary to prevent future endemic conflict between 'races'. For municipal officials the riots justified the future destruction of African shantytowns and the rezoning of Indian residential and trading property for use by whites.