Historical Evolution of Durban's Public Transport System and Challenges For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durban Reality Tour: a Collection of Material About the 'Invisible'

Durban Reality Tour A collection of material about the ‘invisible’ side of the City Llywellyn Leonard, Sufian H Bukurura & Helen Poonen (Compilers) 2008 Durban Reality Tour A collection of material about the ‘invisible’ side of the City Llywellyn Leonard, Sufian H Bukurura & Helen Poonen (Compilers) Contents Maps Durban and surrounding areas Durban Metro South Durban Industries Introduction Part I. News clips 1.1 Street Traders Traders angry over arrests (Sunday Tribune, 24 June 2004) Police battle Durban street traders (Mail & Guardian, 18 June 2007) 1.2 South Durban: Pollution and Urban Health Crisis Struggles against ‘toxic’ petrochemical industries, (B Maguranyanga, 2001) Global day of action hits SHELL & BP (SAPREF) gates (Meindert Korevaar, SDCEA Newsletter, volume 8, November 2006) Health study proves that communities in South Durban face increased health problems due to industrial pollution (Rico Euripidou, groundWork, volume 8 number 3, September 2006) Will city authorities take action to enforce Engen’s permit? (Press Release, South Durban Community Environmental Alliance, 27 January 2006) Engen violates permit conditions, (groundWork Press Release, 7 July 2005) Africa: Shell and Its Neighbours, (groundWork Press Release 24 April 2004) Pipelines to be replaced in polluted areas, (The Mercury, 03 June 2005) Homes threatened by cleanup plans (Tony Carne, The Mercury, 19 June 2006) Aging refineries under fire (Southern Star, 3 November 2006) Multinationals ‘water down South Africa’s Constitution’ (Tony Carne, The Mercury, -

Padayachee, Vishnu : an Analysis of Some Aspects of Employment And

AN ANALYSIS OF SOKE ASPECTS OF EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT IN THE AFRICAN TOWNSHIPS OF maAZI AND LAMOWnILLE - A PBELIMINAEY.INVESTIGATION Vishnu Padayachee Occasional Paper No. 14 . December 1985 ISBN No. 0-949947-75-X Institute for Social and Economic Research University of Durban-Westville Private Bag X54001 DUBBAN 4000 CONTENTS List of Tables Acknowledgements I. Introduction 2. Sampling and Fieldwork 3. General Household Data 4. Profile ot Earners: Demographic, Employment and Income Struc Cure 5. .4 Profile of the Unemployed 6. Summary and Conclusions Footnotes (ii) LlST OF TABLES Table 1 General Household Composition Table 2 Household lncome Structure and Distribution Table 3 Occupational Distribution of Earners Table 4 Length of Present Employment Table 5 Hours Worked by the Employed in the Past Week Table 6 Number of Months Worked in the Past Year Table 7 Distribution of lncome Among Earners Table 8 Distribution by Sex of the Unemployed Table 9 Age Distribution of the Unemployed Table 10 Marital Status of the Unemployed Table I1 Educational Levels of the Unemployed Table 12 Keasons for Unemployment Table 13 Duration of Unemployment Table 14 Methods of Job Search Activity Table 15 Strategies of Survival: Unemployed Persons .vpaeA p~qeqspue sTiezlueu uehg 'sTna? Lapa7 01 os~e'X~~euyj !laded syql jo Su~dXlaql alaldmos 01 aneaI iaq 30 lied dn ahet oqn 'qaTCiapuI eqxruv !yion utysap pue InoXsl InjIyys syq ioj Tienuefl Paid !asyliadxa IeuoTlexndrnos pue Buypos iyaql 103 ialuan UTM pue iapuaho3 lac '1yeN Xex !yionp~aTj aql moqe xuan Xaq~ qs~qn uy Ken luaysyjja pue syqseysnqlua aql ioj iolsoa pun asuaiax !aiyeuuo~lsanb aql 30 uo~~nlsuni~aql 103 Imosw TTaauo !tuypuw~siapun pue asuepp8 'asue~slssealqen~s-A syq ioj orepv-ia~lna uqor iossajoid -1saCoid syql q1p sXen snolieh uy an, padpq or[n slenprnypuy Buyno~~oj aql 01 uorle~~aiddeXm ssaidxa 01 ayrl pTnoqs 1 1. -

Ward Councillors Pr Councillors Executive Committee

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE KNOW YOUR CLLR WEZIWE THUSI CLLR SIBONGISENI MKHIZE CLLR NTOKOZO SIBIYA CLLR SIPHO KAUNDA CLLR NOMPUMELELO SITHOLE Speaker, Ex Officio Chief Whip, Ex Officio Chairperson of the Community Chairperson of the Economic Chairperson of the Governance & COUNCILLORS Services Committee Development & Planning Committee Human Resources Committee 2016-2021 MXOLISI KAUNDA BELINDA SCOTT CLLR THANDUXOLO SABELO CLLR THABANI MTHETHWA CLLR YOGISWARIE CLLR NICOLE GRAHAM CLLR MDUDUZI NKOSI Mayor & Chairperson of the Deputy Mayor and Chairperson of the Chairperson of the Human Member of Executive Committee GOVENDER Member of Executive Committee Member of Executive Committee Executive Committee Finance, Security & Emergency Committee Settlements and Infrastructure Member of Executive Committee Committee WARD COUNCILLORS PR COUNCILLORS GUMEDE THEMBELANI RICHMAN MDLALOSE SEBASTIAN MLUNGISI NAIDOO JANE PILLAY KANNAGAMBA RANI MKHIZE BONGUMUSA ANTHONY NALA XOLANI KHUBONI JOSEPH SIMON MBELE ABEGAIL MAKHOSI MJADU MBANGENI BHEKISISA 078 721 6547 079 424 6376 078 154 9193 083 976 3089 078 121 5642 WARD 01 ANC 060 452 5144 WARD 23 DA 084 486 2369 WARD 45 ANC 062 165 9574 WARD 67 ANC 082 868 5871 WARD 89 IFP PR-TA PR-DA PR-IFP PR-DA Areas: Ebhobhonono, Nonoti, Msunduzi, Siweni, Ntukuso, Cato Ridge, Denge, Areas: Reservoir Hills, Palmiet, Westville SP, Areas: Lindelani C, Ezikhalini, Ntuzuma F, Ntuzuma B, Areas: Golokodo SP, Emakhazini, Izwelisha, KwaHlongwa, Emansomini Areas: Umlazi T, Malukazi SP, PR-EFF Uthweba, Ximba ALLY MOHAMMED AHMED GUMEDE ZANDILE RUTH THELMA MFUSI THULILE PATRICIA NAIR MARLAINE PILLAY PATRICK MKHIZE MAXWELL MVIKELWA MNGADI SIFISO BRAVEMAN NCAYIYANA PRUDENCE LINDIWE SNYMAN AUBREY DESMOND BRIJMOHAN SUNIL 083 7860 337 083 689 9394 060 908 7033 072 692 8963 / 083 797 9824 076 143 2814 WARD 02 ANC 073 008 6374 WARD 24 ANC 083 726 5090 WARD 46 ANC 082 7007 081 WARD 68 DA 078 130 5450 WARD 90 ANC PR-AL JAMA-AH 084 685 2762 Areas: Mgezanyoni, Imbozamo, Mgangeni, Mabedlane, St. -

You'll Never Silence the Voice of the Voiceless

YOU’LL NEVER SILENCE THE VOICE OF THE VOICELESS CRITICAL VOICES OF ACTIVISTS IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA Kate Gunby Richard Pithouse School for International Training South Africa: Reconciliation and Development Fall 2007 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………3 Background……………………………………………………………………………………4 Abahlali………………………………………………………………………………..4 Church Land Programme…..…………………………………………………….........6 Treatment Action Campaign..…………………………………………………….…...7 Methodology…………………………………..……………………………………………..11 Research Limitations.………………………………………………………………...............12 Interview Write-Ups Harriet Bolton…………………….…………………………………………………..13 System Cele…………………………………………………………………………..20 Lindelani (Mashumi) Figlan...………………………………………………………..23 Gary Govindsamy……………………………………………………………….........31 Louisa Motha…………………………………………………………………………39 Kiru Naidoo…………………………………………………………………………..42 David Ntseng…………………………………………………………………………51 Xolani Tsalong……………………………………………………………….............60 Reflection and Discussion...……………………………………………………………….....66 Teach the Masses that Everything Depends on Them…………………………….....66 The ANC Will Stay in Power for a Long Time……………………….......................67 We Want to be Treated as Decent Human Beings like Everyone Else………………69 Just a Piece of Paper Thrown Aside……………………….........................................69 The Tradition of Obedience……………………………………………………….....70 The ANC Has Effectively Demobilized and Decimated Civil Society……………...72 Don’t Talk About Us, Talk To -

DURBAN NORTH 957 Hillcrest Kwadabeka Earlsfield Kenville ^ 921 Everton S!Cteelcastle !C PINETOWN Kwadabeka S Kwadabeka B Riverhorse a !

!C !C^ !.ñ!C !C $ ^!C ^ ^ !C !C !C!C !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C $ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ ñ!C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^ !C ^ !C ñ!C !C ^ ^ !C !C $ ^!C $ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C ñ!.^ $ !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C $ !C !C ñ $ !. !C !C !C !C !C !C !. ^ ñ!C ^ ^ !C $!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !. !C !C ñ!C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ ^ $ ^ !C ñ !C !C !. ñ ^ !C !. !C !C ^ ñ !. ^ ñ!C !C $^ ^ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !C !. ñ !C !C ^ !C ñ!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C !. !C ^ !. !. !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ñ !C !. -

Building Resilience in Glebelands Hostel

‘IF WE SPEAK UP, WE GET SHOT DOWN’ Building resilience in Glebelands Hostel Vanessa Burger August 2019 Acknowledgements The author would like to thank the Global Initiative, members of the media, organizations and individuals for their concern, help, support, advice and encouragement provided over the years – either wittingly or unwittingly. This report was funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Sector Programme Peace and Security, Disaster Risk Management of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). The views and opinions expressed in the report do not necessarily reflect those of the BMZ or the GIZ. All photos: Vanessa Burger, except where specified. © 2019 Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Contents Abbreviations and acronyms ..........................................................................................................................................................iv Glebelands Hostel: Ground zero for political killings ...........................................................................1 Methodology ......................................................................................................................................................................................3 -

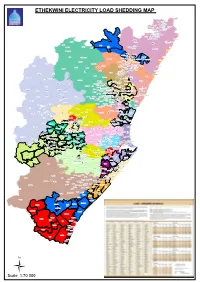

Following Is a Load Shedding Schedule That People Are Advised to Keep

Following is a load shedding schedule that people are advised to keep. STAND-BY LOAD SHEDDING SCHEDULE Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Block A 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 08:00-10:30 Block B 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 14:00-16:30 Block C 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 16:00-18:30 Block D 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 12:00-14:30 Block E 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 10:00-12:30 Block F 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 18:00-20:30 Block G 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 20:00-22:30 Block H 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 04:00-06:30 Block J 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 06:00-08:30 Area Block Albert Park Block D Amanzimtoti Central Block B Amanzimtoti North Block B Amanzimtoti South Block B Asherville Block H Ashley Block J Assagai Block F Athlone Block G Atholl Heights Block J Avoca Block G Avoca Hills Block C Bakerville Gardens Block G Bayview Block B Bellair Block A Bellgate Block F Belvedere Block F Berea Block F Berea West Block F Berkshire Downs Block E Besters Camp Block F Beverly Hills Block C Blair Atholl Block J Blue Lagoon Block D Bluff Block E Bonela Block E Booth Road Industrial Block E Bothas Hill Block F Briardene Block G Briardene -

Kwazulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal Municipality Ward Voting District Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830014 INDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.99047 29.45013 NEXT NDAWANA SENIOR SECONDARY ELUSUTHU VILLAGE, NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830025 MANGENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.06311 29.53322 MANGENI VILLAGE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830081 DELAMZI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09754 29.58091 DELAMUZI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830799 LUKHASINI PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.07072 29.60652 ELUKHASINI LUKHASINI A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830878 TSAWULE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.05437 29.47796 TSAWULE TSAWULE UMZIMKHULU RURAL KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830889 ST PATRIC JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.07164 29.56811 KHAYEKA KHAYEKA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830890 MGANU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -29.98561 29.47094 NGWAGWANE VILLAGE NGWAGWANE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11831497 NDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.98091 29.435 NEXT TO WESSEL CHURCH MPOPHOMENI LOCATION ,NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKHULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830058 CORINTH JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09861 29.72274 CORINTH LOC UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830069 ENGWAQA JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.13608 29.65713 ENGWAQA LOC ENGWAQA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830867 NYANISWENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.11541 29.67829 ENYANISWENI VILLAGE NYANISWENI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830913 EDGERTON PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.10827 29.6547 EDGERTON EDGETON UMZIMKHULU -

Chatsworth - the Making of National Assurance Company, the Country’S Largest a South African Township by Black-Owned Short- Term Insurer

THE JOURNAL OF THE HELEN SUZMAN FOUNDATION | ISSUE 72 | APRIL 2014 BOOK REVIEW Kalim Rajab is a director of the New Chatsworth - The Making of National Assurance Company, the country’s largest a South African Township by black-owned short- term insurer. He is Ashwin Desai and Goolam also a columnist for Daily Maverick. Kalim previously worked for Vahed De Beers in strategy In 1970, the forthright but culturally emancipated Sunday Times and corporate finance in London and columnist, Molly Reinhardt, thought all South Africans should “hang Johannesburg. He their head in shame” at the discrimination hurled by their government was educated at the against the South African Indian population. “No people have suffered Universities of Cape Town and Oxford, as much as the Indian community from ruthless uprooting under the the latter as an Group Areas Act... what it must be like for a cultured, highly civilised, Oppenheimer Scholar. intellectual and sensitive people to accept insulting discrimination is something I cannot bear to think about,” she lamented. The uprooting which she spoke of – a callous, ultimately failed experiment at social reengineering which created deep fissures of physical, social and economic misery not only for Indians but for all non-white South Africans – had a few years previously (in 1961) led to the creation of the Indian township of Chatsworth, twenty kilometres south of Durban. 120,000 people of Indian origin were to be forcibly relocated, often without compensation, to a rural district which lacked adequate roads, drainage, sewage and electricity. A single, poorly maintained highway would connect the township to the city, making it costly and difficult for Indians to make their way there. -

Profile of Poverty in the Durban Region

J .. ~ PROFILE OF POVERTY IN THE DURBAN REGION PROJECT FOR STATISTICS ON LIVING STANDARDS AND DEVELOPMENT PREPARED BY J Cobbledick and M Sharratt Economic Research Unit University of Natal Durban OCTOBER 1993 ~, ~' - ( /) .. During 1992 the World Bank approached the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU) at the University of Cape Town to coordinate, a study in South Africa called the Project on Statistics for Living $tandards and Development. This study was carried out during 1993, and consisteci of two phases. The first of these was a situation analysis, consisting of a number of regional poverty profiles and cross-cutting studies on a na~ional level. The second phase was a country wide household surVey conducted in the latter half of 1993. The Project has been built on the Second Carnegie Inquiry into Poverty, which assessed the situation up to the mid 1980's. Whilst preparation of these papers for the situation analysis, using common guidelines, involved much discussion and criticism amongst all those involved in the Project, the final paper remains the responsibility of its authors. .' -<, '" -) 1 In the series of working papers on reilional poverty and cross- '"" . cutting themes there are 12 papers: Regional Poverty Profiles: Ciskei Durban Eastern and Northern Transvaal NatallKwazulu OFS and Qwa-Qwa Port Elizabeth - Uitenhage PWV' Transkei Western Cape Cross-Cutting Studies: Energy Nutrition Urbanisation & Housing Water Supply TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION No. PAGE No. 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 CONTEXTUALISING THE DURBAN -

Ethekwini Electricity Load Shedding Map

ETHEKWINI ELECTRICITY LOAD SHEDDING MAP Lauriston Burbreeze Wewe Newtown Sandfield Danroz Maidstone Village Emona SP Fairbreeze Emona Railway Cottage Riverside AH Emona Hambanathi Ziweni Magwaveni Riverside Venrova Gardens Whiteheads Dores Flats Gandhi's Hill Outspan Tongaat CBD Gandhinagar Tongaat Central Trurolands Tongaat Central Belvedere Watsonia Tongova Mews Mithanagar Buffelsdale Chelmsford Heights Tongaat Beach Kwasumubi Inanda Makapane Westbrook Hazelmere Tongaat School Jojweni 16 Ogunjini New Glasgow Ngudlintaba Ngonweni Inanda NU Genazano Iqadi SP 23 New Glasgow La Mercy Airport Desainager Upper Bantwana 5 Redcliffe Canelands Redcliffe AH Redcliff Desainager Matata Umdloti Heights Nellsworth AH Upper Ukumanaza Emona AH 23 Everest Heights Buffelsdraai Riverview Park Windermere AH Mount Moreland 23 La Mercy Redcliffe Gragetown Senzokuhle Mt Vernon Oaklands Verulam Central 5 Brindhaven Riyadh Armstrong Hill AH Umgeni Dawncrest Zwelitsha Cordoba Gardens Lotusville Temple Valley Mabedlane Tea Eastate Mountview Valdin Heights Waterloo village Trenance Park Umdloti Beach Buffelsdraai Southridge Mgangeni Mgangeni Riet River Southridge Mgangeni Parkgate Southridge Circle Waterloo Zwelitsha 16 Ottawa Etafuleni Newsel Beach Trenance Park Palmview Ottawa 3 Amawoti Trenance Manor Mshazi Trenance Park Shastri Park Mabedlane Selection Beach Trenance Manor Amatikwe Hillhead Woodview Conobia Inthuthuko Langalibalele Brookdale Caneside Forest Haven Dimane Mshazi Skhambane 16 Lower Manaza 1 Blackburn Inanda Congo Lenham Stanmore Grove End Westham -

Victim Findings ABRAHAMS, Derrek (30), a Street Committee Me M B E R, Was Shot Dead by Members of the SAP at Gelvandale, Port Elizabeth, on 3 September 1990

Vo l u m e S E V E N ABRAHAMS, Ashraf (7), was shot and injured by members of the Railway Police on 15 October 1985 in Athlone, in the TRO J A N HOR S EI N C I D E N T , CAP E TOW N . Victim findings ABRAHAMS, Derrek (30), a street committee me m b e r, was shot dead by members of the SAP at Gelvandale, Port Elizabeth, on 3 September 1990. ■ ABRAHAMS, John (18) (aka 'Gaika'), an MK member, Unknown victims went into exile in 1968. His family last heard from him Many unnamed and unknown South Africans were the in 1975 and has received conflicting information from victims of gross violations of human rights during the the ANC reg a rding his fate. The Commission was Co m m i s s i o n ’s mandate period. Their stories came to unable to establish what happened to Mr Abrahams, the Commission in the stories of other victims and in but he is presumed dead. the accounts of perpetrators of violations. ABRAHAMS, Moegsien (23), was stabbed and stoned to death by a group of UDF supporters in Mitchells Like other victims of political conflict and violence in Plain, Cape Town, on 25 May 1986, during a UDF rally South Africa, they experienced suffering and injury. wh e re it was alleged that he was an informe r. UDF Some died, some lost their homes. Many experienced leaders attempted to shield him from attack but Mr the loss of friends, family members and a livelihood.