San Lean Dro in P Ers Pe Ctiv E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

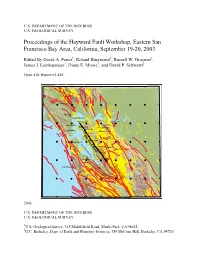

USGS Open-File Report 03-485

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Proceedings of the Hayward Fault Workshop, Eastern San Francisco Bay Area, California, September 19-20, 2003 Edited By David A. Ponce1, Roland Bürgmann2, Russell W. Graymer1, James J. Lienkaemper1, Diane E. Moore1, and David P. Schwartz1 Open-File Report 03-485 Rodgers Cr Fault Petaluma Novato San Pablo Bay Pinole Pt Pittsburg San Rafael Concord Richmond Pleasant Hill El Cerrito Mill Valley Walnut Creek Berkeley Hayward Fault Danville OAKLAND SAN FRANCISCO San Francisco Bay Daly City San Leandro Dublin Livermore Hayward San Mateo FREMONT Calaveras Fault Half Moon Bay Menlo Park Sunnyvale SAN JOSE 2003 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 1U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, CA 94025 2U.C. Berkeley, Dept. of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 389 McCone Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Proceedings of the Hayward Fault Workshop, Eastern San Francisco Bay Area, California, September 19-20, 2003 Edited By David A. Ponce1, Roland Bürgmann2, Russell W. Graymer1, James J. Lienkaemper1, Diane E. Moore1, and David P. Schwartz1 Open-File Report 03-485 2003 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 1U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, CA 94025 2U.C. Berkeley, Dept. of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 389 McCone Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................1 -

Environmental Hazards Incorporates the State-Mandated “Safety” and “Noise” Elements of the General Plan

7 HAZARDS ENVIRONMENTAL A. OVERVIEW Environmental Hazards incorporates the state-mandated “Safety” and “Noise” elements of the General Plan. The Chapter addresses natural and man-made hazards in the City, including earthquakes, landslides, floods, sea level rise, wildfire, air and water pollution, hazardous materials, and aviation accidents. It includes a summary of emergency preparedness in San Leandro, with policies that provide the foundation for disaster planning in the City. The Element also addresses noise issues, with the dual objective of mitigating existing noise problems and avoiding future disturbances and conflicts. The overall purpose of this Element is to minimize the potential for damage and injury resulting from environmental hazards. The State Government Code requires that the Element identify and evaluate the hazards that are present and establish appropriate goals, policies, and action programs to reduce those hazards to acceptable levels. Environmental hazards define basic constraints to land use that must be reflected in how and where development takes place. Public education is critical to the successful implementation of this Element. Although San Leandrans are generally aware that the City is located in “earthquake country,” there is still much that can be done to improve readiness and response when disaster strikes. The Environmental Hazards Element takes a pro-active approach to emergency preparedness, emphasizing mitigation and reduced exposure to hazards as well as response and recovery. This Element is closely coordinated with the City’s Local Hazard Mitigation Plan (LHMP), a federally mandated plan to reduce exposure to hazards and ensure eligibility for federal disaster preparedness and relief funds. 7-1 SAN LEANDRO GENERAL PLAN ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARD S The Element also sets forth a pro-active strategy for addressing noise issues in the community. -

(Oncorhynchus Mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California

Historical Distribution and Current Status of Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California Robert A. Leidy, Environmental Protection Agency, San Francisco, CA Gordon S. Becker, Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA Brett N. Harvey, John Muir Institute of the Environment, University of California, Davis, CA This report should be cited as: Leidy, R.A., G.S. Becker, B.N. Harvey. 2005. Historical distribution and current status of steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward p. 3 Introduction p. 5 Methods p. 7 Determining Historical Distribution and Current Status; Information Presented in the Report; Table Headings and Terms Defined; Mapping Methods Contra Costa County p. 13 Marsh Creek Watershed; Mt. Diablo Creek Watershed; Walnut Creek Watershed; Rodeo Creek Watershed; Refugio Creek Watershed; Pinole Creek Watershed; Garrity Creek Watershed; San Pablo Creek Watershed; Wildcat Creek Watershed; Cerrito Creek Watershed Contra Costa County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 39 Alameda County p. 45 Codornices Creek Watershed; Strawberry Creek Watershed; Temescal Creek Watershed; Glen Echo Creek Watershed; Sausal Creek Watershed; Peralta Creek Watershed; Lion Creek Watershed; Arroyo Viejo Watershed; San Leandro Creek Watershed; San Lorenzo Creek Watershed; Alameda Creek Watershed; Laguna Creek (Arroyo de la Laguna) Watershed Alameda County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 91 Santa Clara County p. 97 Coyote Creek Watershed; Guadalupe River Watershed; San Tomas Aquino Creek/Saratoga Creek Watershed; Calabazas Creek Watershed; Stevens Creek Watershed; Permanente Creek Watershed; Adobe Creek Watershed; Matadero Creek/Barron Creek Watershed Santa Clara County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. -

903 Manor Boulevard Residential Project

903 Manor Boulevard Residential Project Initial Study – Mitigated Negative Declaration prepared by City of San Leandro Community Development Department 835 East 14th Street San Leandro, California 94577 Contact: Andrew Mogensen, AICP, Planning Manager prepared with the assistance of Rincon Consultants, Inc. 449 15th Street, Suite 303 Oakland, California 94612 March 2020 NOTICE OF AVAILABILITY AND INTENT TO ADOPT A MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION FOR 903 MANOR BOULEVARD RESIDENTIAL PROJECT AT 903 MANOR BOULEVARD, SAN LEANDRO, CALIFORNIA 94579 Notice is Hereby Given that the City of San Leandro is considering a recommendation that the project herein identified will have no significant environmental impacts in compliance with Section 15070 of the CEQA Guidelines. A copy of the proposed Mitigated Negative Declaration, Initial Study, and Mitigation Monitoring and Reporting Program are on file in the San Leandro Community Development Department, 835 East 14th Street, San Leandro, California 95477. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, hard copies will be mailed upon request rather than accessible to the public at a physical location. If you need a hardcopy please send a self-addressed 10”x12” envelope with pre-paid postage to City of San Leandro, Planning Division, Attn: Andrew Mogensen, Planning Manager, 835 E. 14th Street, San Leandro, CA 94577. It is also available on the City’s Website at City of San Leandro, Community Development Department, Planning Services, Plans & CEQA Documents: https://www.sanleandro.org/depts/cd/plan/polplanstudiesceqa/default.asp. REVIEW PERIOD: The 20-day review period is from May 15, 2020 to June 4, 2020. Comments on the proposed Mitigated Negative Declaration should be provided in writing to the San Leandro Community Development Department, 835 East 14th Street, San Leandro, California 94577 by June 4, 2020 at 4:00 p.m. -

USGS Open-File Report 96-252, Geologic Explanation Pamphlet

Preliminary geologic map emphasizing bedrock formations in Alameda County, California: A digital database by R.W. Graymer, D.L. Jones, and E.E. Brabb U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 96-252 Geologic Explanation Introduction This map database represents the integration of previously published and unpublished maps by several workers (see Sources of Data) and thousands of man-hours of new geologic mapping and field checking by the authors. The data are released in a preliminary digital form to provide an opportunity for regional planners, local, state, and federal agencies, teachers, consultants, and others interested in geologic data to have the new data long before a traditional paper map is published. The authors currently plan to produce a second version of the geologic map of Alameda County that would include subdivided Quaternary units and enhanced stratigraphic description and nomenclature, both as a digital product and as a traditional paper map. The timing of release of these products, and indeed whether they will be produced at all, depends on a variety of factors, including funding, outside author control. Stratigraphy Lithologic associations in Alameda County are divided into nine assemblages; I, II, and V - XI (Assemblages III and IV occur only in Contra Costa County). As defined in Graymer, Jones, and Brabb (1994), assemblages are large, fault - bounded blocks that contain a unique stratigraphic sequence. The stratigraphic sequence differs from that of neighboring assemblages by containing different rock units (e.g. the freshwater limestone (Tlp) in Assemblage VIII is missing from the other Assemblages), or by different stratigraphic relationship among similar rock units (e.g. -

I. Visual Resources

LSA ASSOCIATES, INC EBRPD WILDFIRE HAZARD REDUCTION AND RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN EIR JULY 2009 IV. SETTING, IMPACTS AND MITIGATION MEASURES I. VISUAL RESOURCES I. VISUAL RESOURCES This section addresses the visual resources for the parks located within the East Bay Regional Park District’s (EBRPD’s) Wildfire Hazard Reduction and Resource Management Plan (Plan) Study Area. Included in this section is a description of existing visual conditions within the Study Area, as well as an evaluation of the potential effects on visual resources from implementation of the Plan. The visual analysis is based on field observations of the Study Area, aerial and ground-level photographs of the Study Area, use of the Google Maps Street View program, and publicly-available planning documents. Within this section, the term “viewshed” is used in reference to the surface area visible from a viewpoint or a series of viewpoints: that portion of the landscape that would be visible from a particular location and which could be visually impacted by changes to vegetation or landforms in those areas. For the purpose of determining potential effects of a project on visual resources within an area, particular viewpoints may be selected because they present a view that is representative of the landscape or reflect a typical viewshed for that area. These viewpoints are then used to describe the visual changes or contrasts that could result from implementation of the proposed project. 1. Setting This section describes the regional context of the Study Area, views within and across the Study Area, applicable EBRPD policies relating to open space and resource management within the Study Area, and concerns related to roadway visibility and safety within the Study Area. -

4.5 Geology and Soils

Environmental Impact Analysis Geology and Soils 4.5 Geology and Soils This section assesses potential impacts related to geologic and soil hazards. 4.5.1 Setting a. Topography and Geology San Leandro is located on the East Bay Plain (the Plain), a flat area that extends 50 miles from Richmond in the north to San Jose in the south. The Plain is about three miles wide in the San Leandro area. At its eastern edge, the plain transitions into low hills, rising to 526 feet at the highest point in the City’s Bay-O-Vista neighborhood. On its western edge, the Plain slopes down to San Francisco Bay, the largest estuary on the California Coast (City of San Leandro 2016i). San Leandro’s rich alluvial soils and temperate climate support a wide variety of plants and animals. Wetlands in the southwest part of San Leandro provide habitat for the salt marsh harvest mouse and other special status species. San Leandro Creek remains one of the few waterways in the urbanized East Bay that retains its natural character along most of its course (City of San Leandro 2016i). San Leandro is located within the United States Geological Survey’s (USGS) San Leandro and Hayward Quadrangle 7.5-minute topographic map areas. The area is typified by low topographic relief, with gentle slopes to the southwest in the direction of San Francisco Bay. By contrast, the San Leandro Hills that lie directly northeast of San Leandro have more pronounced topographic relief, with elevations that locally approach 1,000 feet above mean sea level (City of San Leandro 2016i). -

East Bay Greenway Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration

EAST BAY GREENWAY PROJECT INITIAL STUDY AND PROPOSED MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION Prepared for Alameda County Transportation Commission 1333 Broadway, Suite 300 Oakland, CA 94612 June 2012 Prepared by HQE Incorporated URS Corporation 1814 Franklin St., Suite 700 1333 Broadway, Suite Oakland, CA 94612 800 Oakland, CA 94612 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1. Introduction and Regulatory Guidance .................................................... 1-1 1.2. Lead Agency ............................................................................................ 1-1 1.3. Purpose ..................................................................................................... 1-1 1.4. Summary of Findings ............................................................................... 1-2 2.0 Project Description ......................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1. Project Location ....................................................................................... 2-1 2.2. Project Study Area ................................................................................... 2-1 2.3. Project Background .................................................................................. 2-2 2.3.1. East Bay Greenway Concept Plan and Funding .......................... 2-2 2.3.2. Regional and Local Plan ............................................................. -

RCRA Facility Investigation Report

E.O. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory United States Department of Energy University of California Environmental Restoration Program RCRA Facility Investigation Report for the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory ENVIRONMENTAL RESTORATION PROGRAM September 2000 Note: The draft final RCRA Facility Investigation Report (RFI) Report, for the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Environmental Restoration Program, dated September 2000, was approved by the Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) as final. The final RCRA Facility Investigation Report (RFI) Report contained herein consists of the draft final document accompanied by the DTSC approval letter dated July 27, 2001. E.O. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory United States Department of Energy University of California Environmental Restoration Program DRAFT FINAL RCRA Facility Investigation Report for the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory ENVIRONMENTAL RESTORATION PROGRAM September 2000 DRAFT FINAL RCRA Facility Investigation Report for the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory ENVIRONMENTAL RESTORATION PROGRAM A Joint Effort of Environment, Health and Safety Division and Earth Sciences Division Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 and Parsons Engineering Science, Inc. Oakland, California September 2000 This work was done at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory operated by the University of California for the U. S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC03-76SF00098. ERP RFI Report ii September 29, 2000 DRAFT FINAL ERP RFI Report -

Geologic Assessment Addendum 2010.Doc 1 AGS

AC Transit East Bay Bus Rapid Transit Project in Alameda County Final Environmental Impact Statement/Environmental Impact Report Pursuant to National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, §102 (42 U.S.C. §4332); Federal Transit Laws (49 U.S.C. §5301(e), §5323(b) and §5324(b)); National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, §106 (16 U.S.C. §470f); 40 CFR Parts 1500-1508; 23 CFR Part 771; Executive Order 12898 (Environmental Justice); and California Environmental Quality Act, PRC 21000 et seq.; and the State of California CEQA Guidelines, California Administrative Code, 15000 et seq. by the U.S. Department of Transportation/Federal Transit Administration and the Alameda Contra Costa Transit District Geologic Assessment Addendum December 2010 DRAFT GEOLOGIC ASSESSMENT ADDENDUM AC TRANSIT EAST BAY BRT EIS/R ALAMEDA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: KIMLEY-HORN AND ASSOCIATES, INC. Submitted by: AGS, INC. DECEMBER 2010 AGS, Inc., 5 Freelon Street, San Francisco, CA 94107 AGS This addendum presents the results of a review of the Geologic Assessment conducted for the AC Transit East Bay BRT project in 2005. Some of the main points from the Geologic Assessment are as follows: • The project corridor is located in a seismically active region, which has been subjected to several strong earthquakes during historic time; however, no active faults are known to cross the project corridor. The Hayward Fault lies between 0.4 and 4.3 miles (0.64 and 7.0 kilometers) northeast of the project corridor, closest at both the northern and southern ends, and dominates the seismic hazard due to its proximity. The other major active faults, which could cause significant shaking of the project area, are the San Andreas, Concord, Calaveras, Rodgers Creek, and San Gregorio Faults. -

Upper Cretaceous and Lower Tertiary Rocks Berkeley and San Leandro Hills California

Upper Cretaceous and Lower Tertiary Rocks Berkeley and San Leandro Hills California GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1251-J Upper Cretaceous and Lower Tertiary Rocks Berkeley and San Leandro Hills California By J. E. CASE CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1251-J A revision of the stratigraphy of miogeosynclinal Upper Cretaceous rocks and a brief description of newly recognized Paleocene and Eocene marine beds UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1968 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract__ ___-__--_-_--__-----_--__---_______-__________________ Jl Introduction. __---__--__-_-_--_--__-____-_______________________-_ 1 Acknowledgments. ----____-_---_____-______.__________________ 3 Regional geologic setting.__________________________________________ 3 Stratigraphy-__---__-_----_---_----__-_-_-__--____________________ 4 Jurassic and Cretaceous rocks._------_--_--____-________________ 6 Franciscan Formation______________________________________ 6 Upper Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous rocks_______________________ 7 Knoxville Formation and jEJwcMo-bearing beds.________________ 7 Missing Early Cretaceous interval.__________-______-----____ 8 Upper Cretaceous rocks._______________________________________ 8 Joaquin Miller Formation._________________________________ 10 Oakland Conglomerate._-_-__-_______-___---_____-____-___- -

San Leandro General Plan Update Draft Environmental Impact Report

Draft Environmental Impact Report San Leandro General Plan Update Prepared by: City of San Leandro Barry Miller, AICP Planning Consultant SCH# 2001092001 November, 2001 DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT SAN LEANDRO GENERAL PLAN UPDATE TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents SUMMARY OF IMPACTS AND MITIGATION ...................................................................... S-1 I. INTRODUCTION Background .......................................................................................................................I-1 General Plans and CEQA..................................................................................................I-2 Program EIR Scope and Format .......................................................................................I-2 Organization of the EIR ....................................................................................................I-3 II. PROJECT DESCRIPTION Definition of the Project ................................................................................................. II-1 Location and Setting ....................................................................................................... II-1 Project Context ............................................................................................................... II-3 Summary of Project ........................................................................................................ II-8 Major Departures from the 1989 General Plan ............................................................. II-20 Required