The Carlyle Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Carlyle Society Papers

THE CARLYLE SOCIETY SESSION 2011-2012 OCCASIONAL PAPERS 24 • Edinburgh 2011 1 2 President’s Letter With another year’s papers we approach an important landmark in Carlyle studies. A full programme for the Society covers the usual wide range (including our mandated occasional paper on Burns), and we will also make room for one of the most important of Thomas’s texts, the Bible. 2012 sees a milestone in the publication of volume 40 of the Carlyle Letters, whose first volumes appeared in 1970 (though the project was a whole decade older in the making). There will be a conference (10-12 July) of academic Carlyle specialists in Edinburgh to mark the occasion – part of the wider celebrations that the English Literature department will be holding to celebrate its own 250th anniversary of Hugh Blair’s appointment to the chair of Rhetoric, making Edinburgh the first recognisable English department ever. The Carlyle Letters have been an important part of the research activity of the department for nearly half a century, and there will also be a public lecture later in November (when volume 40 itself should have arrived in the country from the publishers in the USA). As part of the conference there will be a Thomas Green lecture, and members of the Society will be warmly invited to attend this and the reception which follows. Details are in active preparation, and the Society will be kept informed as the date draws closer. Meantime work on the Letters is only part of the ongoing activity, on both sides of the Atlantic, to make the works of both Carlyles available, and to maintain the recent burst of criticism which is helping make their importance in the Victorian period more and more obvious. -

List of the Old Parish Registers of Scotland 758-811

List of the Old Parish Registers Dumfries OPR DUMFRIES 812. ANNAN 812/1 B 1703-1819 M 1764-1819 D - 812/2 B 1820-54 M - D - 812/3 B - M 1820-54 D - RNE 813A. APPLEGARTH AND SIBBALDBIE A 813 /1 B 1749-1819 M 1749-1824 D 1749-1820 A 813 /2 B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D 1820-54 See library reference MT 220.014 for deaths and burial index, 1749- 1854 813B. BRYDEKIRK B 813 /1 1836-54 M 1836-54 D - 814. CANONBIE 814/1 B 1693-1768 M - D - 814/2 B 1768-1820 M 1768-1820 D 1783-1805 814/3 B 1820-54 M 1820-43 D - RNE See library reference MT 220.006 for index to deaths and burials1786- 1805 815. CAERLAVEROCK 815/1 B 1749-1819 M 1753-1819 D 1753-75 815/2 B 1820-54 M 1826-39 D 1826-54 816. CLOSEBURN 816/1 B 1765-1819 M 1766-1817 D 1765-1815 816/2 B 1819-54 M 1823-48 D 1820-47 RNE 817. CUMMERTREES 817/1 B 1749-1846 M 1786-1854 D 1733-83 817/2 B 1820-54 M 1848-54 D 1831-38 818. DALTON 818/1 B 1723-1819 M 1766-1824 D 1766-1817 818/2 B - M 1769-1804 D 1779-1804 818/3 B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D - List of the Old Parish Registers Dumfries OPR 819. DORNOCK 819/1 B 1773-1819 M 1774-1818 D 1774-83 819/2 B 1820-54 M 1828-54 D - Contains index to B 1845-54 820. -

Volume 78 Cover

Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society LXXVIII 2004 Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society FOUNDED 20th NOVEMBER, 1862 THIRD SERIES VOLUME LXXVIII Editors: JAMES WILLIAMS, F.S.A.Scot., R. McEWEN ISSN 0141-1292 2004 DUMFRIES Published by the Council of the Society Office-Bearers 2003-2004 and Fellows of the Society President Mrs E Toolis Vice Presidents Mrs J Brann, Mr J Neilson, Miss M Stewart and Mrs M Williams Fellows of the Society Dr J Harper, MBE; Mr J Banks, BSc; Mr A E Truckell, MBE, MA, FMA; Mr A Anderson, BSc; Mr D Adamson, MA; Mr J Chinnock; Mr J H D Gair, MA, JP; Dr J B Wilson, MD and Mr K H Dobie – as Past Presidents. Mr J Williams and Mr L J Masters, MA – appointed under Rule 10. Hon. Secretary Mr R McEwen, 5 Arthur’s Place, Lockerbie DG11 2EB Tel. (01576) 202101 Hon. Membership Secretary Miss H Barrington, 30A Noblehill Avenue, Dumfries DG1 3HR Hon. Treasurer Mr L Murray, 24 Corberry Park, Dumfries DG2 7NG Hon. Librarian Mr R Coleman, 2 Loreburn Park, Dumfries DG1 1LS Tel. (01387) 247297 Assisted by Mr J Williams, 43 New Abbey Road, Dumfries DG2 7LZ Joint Hon. Editors Mr J Williams and Mr R McEwen Hon. Curators Mrs E Kennedy and Ms S Ratchford, both Dumfries Museum Ordinary Members Mrs A Clark, Mr I Cochrane-Dyet, Dr D Devereux, Dr S Graham, Dr B Irving, Mr J McKinnell, Mr I McClumpha, Mr M Taylor, Dr A Terry and Mr M White, Mr J L Williams. -

Report on the Current Position of Poverty and Deprivation in Dumfries and Galloway 2020

Dumfries and Galloway Council Report on the current position of Poverty and Deprivation in Dumfries and Galloway 2020 3 December 2020 1 Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. National Context 2 3. Analysis by the Geographies 5 3.1 Dumfries and Galloway – Geography and Population 5 3.2 Geographies Used for Analysis of Poverty and Deprivation Data 6 4. Overview of Poverty in Dumfries and Galloway 10 4.1 Comparisons with the Crichton Institute Report and Trends over Time 13 5. Poverty at the Local Level 16 5.1 Digital Connectivity 17 5.2 Education and Skills 23 5.3 Employment 29 5.4 Fuel Poverty 44 5.5 Food Poverty 50 5.6 Health and Wellbeing 54 5.7 Housing 57 5.8 Income 67 5.9 Travel and Access to Services 75 5.10 Financial Inclusion 82 5.11 Child Poverty 85 6. Poverty and Protected Characteristics 88 6.1 Age 88 6.2 Disability 91 6.3 Gender Reassignment 93 6.4 Marriage and Civil Partnership 93 6.5 Pregnancy and Maternity 93 6.6 Race 93 6.7 Religion or Belief 101 6.8 Sex 101 6.9 Sexual Orientation 104 6.10 Veterans 105 7. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Poverty in Scotland 107 8. Summary and Conclusions 110 8.1 Overview of Poverty in Dumfries and Galloway 110 8.2 Digital Connectivity 110 8.3 Education and Skills 111 8.4 Employment 111 8.5 Fuel Poverty 112 8.6 Food Poverty 112 8.7 Health and Wellbeing 113 8.8 Housing 113 8.9 Income 113 8.10 Travel and Access to Services 114 8.11 Financial Inclusion 114 8.12 Child Poverty 114 8.13 Change Since 2016 115 8.14 Poverty and Protected Characteristics 116 Appendix 1 – Datazones 117 2 1. -

Thomas Carlyle and Juniper Green

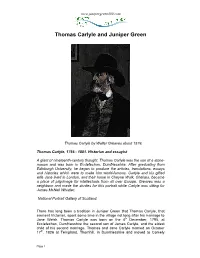

www.junipergreen300.com Thomas Carlyle and Juniper Green Thomas Carlyle by Walter Greaves about 1879. Thomas Carlyle, 1795 - 1881. Historian and essayist A giant of nineteenth-century thought, Thomas Carlyle was the son of a stone- mason and was born in Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire. After graduating from Edinburgh University, he began to produce the articles, translations, essays and histories which were to make him world-famous. Carlyle and his gifted wife Jane lived in London, and their home in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, became a place of pilgrimage for intellectuals from all over Europe. Greaves was a neighbour and made the studies for this portrait while Carlyle was sitting for James McNeil Whistler. National Portrait Gallery of Scotland. There has long been a tradition in Juniper Green that Thomas Carlyle, that eminent Victorian, spent some time in the village not long after his marriage to Jane Welsh. Thomas Carlyle was born on the 4th December, 1795, at Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire the second son of James Carlyle, and the eldest child of his second marriage. Thomas and Jane Carlyle married on October 17th, 1826 at Templand, Thornhill, in Dumfriesshire and moved to Comely Page 1 Bank, Edinburgh, their first home, on the same day. It follows that any sojourn by Carlyle in Juniper Green must have been in the late 1820s. The earliest mention of this tradition so far found is in ‘Old and New Edinburgh’ by James Grant Vol. III Chapter XXXVIII p. 323 where it states: “Near Woodhall in the parish of Colinton, is the little modern village of Juniper Green, chiefly celebrated as being the temporary residence of Thomas Carlyle some time after his marriage at Comely Bank, Stockbridge where, as he tells us in his “Reminiscences” (edited by Mr Froude), “his first experience in the difficult task of housekeeping began”. -

Fhs Pubs List

Dumfries & Galloway FHS Publications List – 11 July 2013 Local History publications Memorial Inscriptions Price Wt Castledykes Park Dumfries £3.50 63g Mochrum £4.00 117g Annan Old Parish Church £3.50 100g Moffat £3.00 78g Covenanting Sites in the Stewartry: Stewartry Museum £1.50 50g Annan Old Burial Ground £3.50 130g Mouswald £2.50 65g Dalbeattie Parish Church (Opened 1843) £4.00 126g Applegarth and Sibbaldbie £2.00 60g Penpont £4.00 130g Family Record (recording family tree), A4: Aberdeen & NESFHS £3.80 140g Caerlaverock (Carlaverock) £3.00 85g Penninghame (N Stewart) £3.00 90g From Auchencairn to Glenkens&Portpatrick;Journal of D. Gibson 1814 -1843 : Macleod £4.50 300g Cairnryan £3.00 60g *Portpatrick New Cemetery £3.00 80g Canonbie £3.00 92g Portpatrick Old Cemetery £2.50 80g From Durisdeer & Castleton to Strachur: A Farm Diary 1847 - 52: Macleod & Maxwell £4.50 300g *Carsphairn £2.00 67g Ruthwell £3.00 95g Gaun Up To The Big Schule: Isabelle Gow [Lockerbie Academy] £10.00 450g Clachan of Penninghame £2.00 70g Sanquhar £4.00 115g Glenkens Schools over the Centuries: Anna Campbell £7.00 300g Closeburn £2.50 80g Sorbie £3.50 95g Heritage of the Solway J.Hawkins : Friends of Annandale & Eskdale Museums £12.00 300g Corsock MIs & Hearse Book £2.00 57g Stoneykirk and Kirkmadrine £2.50 180g History of Sorbie Parish Church: Donna Brewster £3.00 70g Cummertrees & Trailtrow £2.00 64g Stranraer Vol. 1 £2.50 130g Dalgarnock £2.00 70g Stranraer Vol. 2 £2.50 130g In the Tracks of Mortality - Robert Paterson, 1716-1801, Stonemason £3.50 90g Dalton £2.00 55g Stranraer Vol. -

History of the Lands and Their Owners in Galloway

H.E NTIL , 4 Pfiffifinfi:-fit,mnuuugm‘é’r§ms, ».IVI\ ‘!{5_&mM;PAmnsox, _ V‘ V itbmnvncn. if,‘4ff V, f fixmmum ‘xnmonasfimwini cAa'1'm-no17t§1[.As'. xmgompnxenm. ,7’°':",*"-‘V"'{";‘.' ‘9“"3iLfA31Dan1r,_§v , qyuwgm." “,‘,« . ERRATA. Page 1, seventeenth line. For “jzim—g1'é.r,”read "j2'1r11—gr:ir." 16. Skaar, “had sasiik of the lands of Barskeoch, Skar,” has been twice erroneously printed. 19. Clouden, etc., page 4. For “ land of,” read “lands of.” 24. ,, For “ Lochenket," read “ Lochenkit.” 29.,9 For “ bo,” read “ b6." 48, seventh line. For “fill gici de gord1‘u1,”read“fill Riei de gordfin.” ,, nineteenth line. For “ Sr,” read “ Sr." 51 I ) 9 5’ For “fosse,” read “ fossé.” 63, sixteenth line. For “ your Lords,” read “ your Lord’s.” 143, first line. For “ godly,” etc., read “ Godly,” etc. 147, third line. For “ George Granville, Leveson Gower," read without the comma.after Granville. 150, ninth line. For “ Manor,” read “ Mona.” 155,fourth line at foot. For “ John Crak,” read “John Crai ." 157, twenty—seventhline. For “Ar-byll,” read “ Ar by1led.” 164, first line. For “ Galloway,” read “ Galtway.” ,, second line. For “ Galtway," read “ Galloway." 165, tenth line. For “ King Alpine," read “ King Alpin." ,, seventeenth line. For “ fosse,” read “ fossé.” 178, eleventh line. For “ Berwick,” read “ Berwickshire.” 200, tenth line. For “ Murmor,” read “ murinor.” 222, fifth line from foot. For “Alfred-Peter,” etc., read “Alfred Peter." 223 .Ba.rclosh Tower. The engraver has introduced two figures Of his own imagination, and not in our sketch. 230, fifth line from foot. For “ his douchter, four,” read “ his douchter four.” 248, tenth line. -

Dumfriesshire

Dumfriesshire Rare Plant Register 2020 Christopher Miles An account of the known distribution of the rare or scarce native plants in Dumfriesshire up to the end of 2019 Rare Plant Register Dumfriesshire 2020 Holy Grass, Hierochloe odorata Black Esk July 2019 2 Rare Plant Register Dumfriesshire 2020 Acknowledgements My thanks go to all those who have contributed plant records in Dumfriesshire over the years. Many people have between them provided hundreds or thousands of records and this publication would not have been possible without them. More particularly, before my recording from 1996 onwards, plant records have been collected and collated in three distinct periods since the nineteenth century by previous botanists working in Dumfriesshire. The first of these was George F. Scott- Elliot. He was an eminent explorer and botanist who edited the first and only Flora so far published for Dumfriesshire in 1896. His work was greatly aided by other contributing botanists probably most notably Mr J.T. Johnstone and Mr W. Stevens. The second was Humphrey Milne-Redhead who was a GP in Mainsriddle in Kircudbrightshire from 1947. He was both the vice county recorder for Bryophytes and for Higher Plants for all three Dumfries and Galloway vice counties! During his time the first systematic recording was stimulated by work for the first Atlas of the British Flora (1962). He published a checklist in 1971/72. The third period of recording was between 1975 and 1993 led by Stuart Martin and particularly Mary Martin after Stuart’s death. Mary in particular continued systematic recording and recorded for the monitoring scheme in 1987/88. -

127179758.23.Pdf

—>4/ PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY THIRD SERIES VOLUME II DIARY OF GEORGE RIDPATH 1755-1761 im DIARY OF GEORGE RIDPATH MINISTER OF STITCHEL 1755-1761 Edited with Notes and Introduction by SIR JAMES BALFOUR PAUL, C.V.O., LL.D. EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. A. Constable Ltd. for the Scottish History Society 1922 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION DIARY—Vol. I. DIARY—You II. INDEX INTRODUCTION Of the two MS. volumes containing the Diary, of which the following pages are an abstract, it was the second which first came into my hands. It had found its way by some unknown means into the archives in the Offices of the Church of Scotland, Edinburgh ; it had been lent about 1899 to Colonel Milne Home of Wedderburn, who was interested in the district where Ridpath lived, but he died shortly after receiving it. The volume remained in possession of his widow, who transcribed a large portion with the ultimate view of publication, but this was never carried out, and Mrs. Milne Home kindly handed over the volume to me. It was suggested that the Scottish History Society might publish the work as throwing light on the manners and customs of the period, supplementing and where necessary correcting the Autobiography of Alexander Carlyle, the Life and Times of Thomas Somerville, and the brilliant, if prejudiced, sketch of the ecclesiastical and religious life in Scotland in the eighteenth century by Henry Gray Graham in his well-known work. When this proposal was considered it was found that the Treasurer of the Society, Mr. -

Outlines of English and American Literature

Outlines of English and American Literature William J. Long Outlines of English and American Literature Table of Contents Outlines of English and American Literature........................................................................................................1 William J. Long..............................................................................................................................................2 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................4 OUTLINES OF ENGLISH LITERATURE...............................................................................................................6 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION: AN ESSAY OF LITERATURE..............................................................7 CHAPTER II. BEGINNINGS OF ENGLISH LITERATURE...................................................................10 CHAPTER III. THE AGE OF CHAUCER AND THE REVIVAL OF LEARNING (1350−1550)...........26 CHAPTER IV. THE ELIZABETHAN AGE (1550−1620).........................................................................42 CHAPTER V. THE PURITAN AGE AND THE RESTORATION (1625−1700).....................................70 CHAPTER VI. EIGHTEENTH−CENTURY LITERATURE....................................................................88 CHAPTER VII. THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY.....................................................................115 CHAPTER VIII. THE VICTORIAN AGE (1837−1901)..........................................................................145 -

Flood Risk Management Strategy Solway Local Plan District Section 3

Flood Risk Management Strategy Solway Local Plan District This section provides supplementary information on the characteristics and impacts of river, coastal and surface water flooding. Future impacts due to climate change, the potential for natural flood management and links to river basin management are also described within these chapters. Detailed information about the objectives and actions to manage flooding are provided in Section 2. Section 3: Supporting information 3.1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 31 1 3.2 River flooding ......................................................................................... 31 2 • Esk (Dumfriesshire) catchment group .............................................. 31 3 • Annan catchment group ................................................................... 32 1 • Nith catchment group ....................................................................... 32 7 • Dee (Galloway) catchment group ..................................................... 33 5 • Cree catchment group ...................................................................... 34 2 3.3 Coastal flooding ...................................................................................... 349 3.4 Surface water flooding ............................................................................ 359 Solway Local Plan District Section 3 310 3.1 Introduction In the Solway Local Plan District, river flooding is reported across five distinct river catchments. -

Proposed Plan

Dumfries and Galloway Council LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2 Proposed Plan JANUARY 2018 www.dumgal.gov.uk Please call 030 33 33 3000 to make arrangements for translation or to provide information in larger type or audio tape. Proposed Plan The Proposed Plan is the settled view of Dumfries and Galloway Council.Copiesof the Plan and supporting documents can be viewed at all Council planning offices, local libraries and online at www.dumgal.gov.uk/LDP2 The Plan along with its supporting documents is published on 29 January 2018 for eight weeks during which representations can be made. Representations can be made to the Plan and any of the supporting documents at any time during the representation period. The closing date for representations is 4pm on $SULO 2018. Representations received after the closing date will not be accepted. When making a representation you must tell us: • What part of the plan your representation relates to, please state the policy reference, paragraph number or site reference; • Whether or not you want to see a change; • What the change is and why. Representations made to the Proposed Plan should be concise at no more than 2,000 words plus any limited supporting documents. The representation should also fully explain the issue or issues that you want considered at the examination as there is no automatic opportunity to expand on the representation later on in the process. Representations should be made using the representation form. An online and pdf version is available at www.dumgal.gov.uk/LDP2 , paper copies are also available at all Council planning offices, local libraries and from the development plan team at the address below.