Does Host Specialization Impact Nematode Parasite Life History and Fecundity?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baylisascariasis

Baylisascariasis Importance Baylisascaris procyonis, an intestinal nematode of raccoons, can cause severe neurological and ocular signs when its larvae migrate in humans, other mammals and birds. Although clinical cases seem to be rare in people, most reported cases have been Last Updated: December 2013 serious and difficult to treat. Severe disease has also been reported in other mammals and birds. Other species of Baylisascaris, particularly B. melis of European badgers and B. columnaris of skunks, can also cause neural and ocular larva migrans in animals, and are potential human pathogens. Etiology Baylisascariasis is caused by intestinal nematodes (family Ascarididae) in the genus Baylisascaris. The three most pathogenic species are Baylisascaris procyonis, B. melis and B. columnaris. The larvae of these three species can cause extensive damage in intermediate/paratenic hosts: they migrate extensively, continue to grow considerably within these hosts, and sometimes invade the CNS or the eye. Their larvae are very similar in appearance, which can make it very difficult to identify the causative agent in some clinical cases. Other species of Baylisascaris including B. transfuga, B. devos, B. schroeder and B. tasmaniensis may also cause larva migrans. In general, the latter organisms are smaller and tend to invade the muscles, intestines and mesentery; however, B. transfuga has been shown to cause ocular and neural larva migrans in some animals. Species Affected Raccoons (Procyon lotor) are usually the definitive hosts for B. procyonis. Other species known to serve as definitive hosts include dogs (which can be both definitive and intermediate hosts) and kinkajous. Coatimundis and ringtails, which are closely related to kinkajous, might also be able to harbor B. -

Gastrointestinal Helminthic Parasites of Habituated Wild Chimpanzees

Aus dem Institut für Parasitologie und Tropenveterinärmedizin des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Gastrointestinal helminthic parasites of habituated wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in the Taï NP, Côte d’Ivoire − including characterization of cultured helminth developmental stages using genetic markers Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Veterinärmedizin an der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Sonja Metzger Tierärztin aus München Berlin 2014 Journal-Nr.: 3727 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Dekan: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jürgen Zentek Erster Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Georg von Samson-Himmelstjerna Zweiter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Heribert Hofer Dritter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Achim Gruber Deskriptoren (nach CAB-Thesaurus): chimpanzees, helminths, host parasite relationships, fecal examination, characterization, developmental stages, ribosomal RNA, mitochondrial DNA Tag der Promotion: 10.06.2015 Contents I INTRODUCTION ---------------------------------------------------- 1- 4 I.1 Background 1- 3 I.2 Study objectives 4 II LITERATURE OVERVIEW --------------------------------------- 5- 37 II.1 Taï National Park 5- 7 II.1.1 Location and climate 5- 6 II.1.2 Vegetation and fauna 6 II.1.3 Human pressure and impact on the park 7 II.2 Chimpanzees 7- 12 II.2.1 Status 7 II.2.2 Group sizes and composition 7- 9 II.2.3 Territories and ranging behavior 9 II.2.4 Diet and hunting behavior 9- 10 II.2.5 Contact with humans 10 II.2.6 -

Biology Two DOL38 - 41

III. Phylum Platyhelminthes A. General characteristics All About Worms! 1. flat worms a. distinct head & tail ends 2. bilateral symmetry 3. habitat = free-living aquatic or parasitic *a. Parasite = heterotroph that gets its nutrients from the living organisms in/on which they live Ph. Platyhelminthes Ph. Nematoda Ph. Annelida 4. motile 5. carnivores or detritivores 6. reproduce sexually & asexually Biology Two DOL38 - 41 7/4/2016 B. Anatomy 3. Simple nervous system 1. have 3 body layers w/ true tissues a. brain-like ganglia in head & organs b. 2 longitudinal nerves with a. inner = endoderm transverse nerves across body b. middle = mesoderm 4. Lack respiratory, circulatory systems c. outer = ectoderm 5. Parasitic forms lack digestive & excretory systems 2. are acoelomates - lack a coelom around internal organs a. use diffusion to supply needs from host organisms a. digestive tract is formed of endoderm 6. Planaria anat. 7. Tapeworm anat. a. flat body w/ arrow-shaped head & a. head = scolex tapered tail 1) has hooks to help hold onto host b. light-sensitive eyespots on head 2) has suckers to ingest food c. body covered in cilia & mucus to aid b. body segments = proglottids movement 1) new ones form right behind head d. digestive tract only open at mouth 2) each segment produces gametes 1) in center of ventral surface 3) each houses excretory organs 2) used for feeding, excretion C. Physiology 1. Digestion (free-living) a. pharynx extends out of mouth b. sucks food into intestines for digestion c. excretory pores & mouth/pharynx remove wastes 2. Reproduction varies a. Sexual for free-living (& some parasites) 1) hermaphrodites a) cross-fertilize or self-fertilize internally b. -

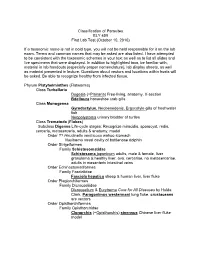

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

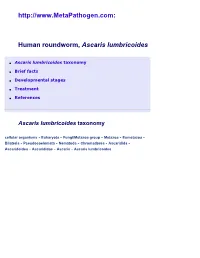

Ascaris Lumbricoides, Roundworm, Causative Agent Of

http://www.MetaPathogen.com: Human roundworm, Ascaris lumbricoides ● Ascaris lumbricoides taxonomy ● Brief facts ● Developmental stages ● Treatment ● References Ascaris lumbricoides taxonomy cellular organisms - Eukaryota - Fungi/Metazoa group - Metazoa - Eumetazoa - Bilateria - Pseudocoelomata - Nematoda - Chromadorea - Ascaridida - Ascaridoidea - Ascarididae - Ascaris - Ascaris lumbricoides Brief facts ● Together with human hookworms (Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus also described at MetaPathogen) and whipworms (Trichuris trichiura), Ascaris lumbricoides (human roundworms) belong to a group of so-called soil-transmitted helminths that represent one of the world's most important causes of physical and intellectual growth retardation. ● Today, ascariasis is among the most important tropical diseases in humans with more than billion infected people world-wide. Ascariasis is mostly seen in tropical and subtropical countries because of warm and humid conditions that facilitate development and survival of eggs. The majority of infections occur in Asia (up to 73%), followed by Africa (~12%) and Latin America (~8%). ● Ascaris lumbricoides is one of six worms listed and named by Linnaeus. Its name has remained unchanged up to date. ● Ascariasis is an ancient infection, and A. lumbricoides have been found in human remains from Peru dating as early as 2277 BC. There are records of A. lumbricoides in Egyptian mummy dating from 1938 to 1600 BC. Despite of long history of awareness and scientific observations, the parasite's life cycle in humans, including the migration of the larval stages around the body, was discovered only in 1922 by a Japanese pediatrician, Shimesu Koino. ● Unlike the hookworm, whose third-stage (L3) larvae actively penetrate skin, A. lumbricoides (as well as T. trichiura) is transmitted passively within the eggs after being swallowed by the host as a result of fecal contamination. -

Parasites of South African Wildlife. XIX. the Prevalence of Helminths in Some Common Antelopes, Warthogs and a Bushpig in the Limpopo Province, South Africa

Page 1 of 11 Original Research Parasites of South African wildlife. XIX. The prevalence of helminths in some common antelopes, warthogs and a bushpig in the Limpopo province, South Africa Authors: Little work has been conducted on the helminth parasites of artiodactylids in the northern 1 Ilana C. van Wyk and western parts of the Limpopo province, which is considerably drier than the rest of the Joop Boomker1 province. The aim of this study was to determine the kinds and numbers of helminth that Affiliations: occur in different wildlife hosts in the area as well as whether any zoonotic helminths were 1Department of Veterinary present. Ten impalas (Aepyceros melampus), eight kudus (Tragelaphus strepsiceros), four blue Tropical Diseases, University wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus), two black wildebeest (Connochaetes gnou), three gemsbok of Pretoria, South Africa (Oryx gazella), one nyala (Tragelaphus angasii), one bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus), one Correspondence to: waterbuck (Kobus ellipsiprymnus), six warthogs (Phacochoerus aethiopicus) and a single bushpig Ilana van Wyk (Potamochoerus porcus) were sampled from various localities in the semi-arid northern and western areas of the Limpopo province. Email: [email protected] New host–parasite associations included Trichostrongylus deflexus from blue wildebeest, Postal address: Agriostomum gorgonis from black wildebeest, Stilesia globipunctata from the waterbuck and Private bag X04, Fasciola hepatica in a kudu. The mean helminth burden, including extra-gastrointestinal Onderstepoort 0110, South Africa helminths, was 592 in impalas, 407 in kudus and blue wildebeest, 588 in black wildebeest, 184 in gemsbok, and 2150 in the waterbuck. Excluding Probstmayria vivipara, the mean helminth Dates: burden in warthogs was 2228 and the total nematode burden in the bushpig was 80. -

Parasitic Nematodes of Pool Frog (Pelophylax Lessonae) in the Volga Basin

Journal MVZ Cordoba 2019; 24(3):7314-7321. https://doi.org/10.21897/rmvz.1501 Research article Parasitic nematodes of Pool Frog (Pelophylax lessonae) in the Volga Basin Igor V. Chikhlyaev1 ; Alexander B. Ruchin2* ; Alexander I. Fayzulin1 1Institute of Ecology of the Volga River Basin, Russian Academy of Sciences, Togliatti, Russia 2Mordovia State Nature Reserve and National Park «Smolny», Saransk, Russia. *Correspondence: [email protected] Received: Febrary 2019; Accepted: July 2019; Published: August 2019. ABSTRACT Objetive. Present a modern review of the nematodes fauna of the pool frog Pelophylax lessonae (Camerano, 1882) from Volga basin populations on the basis of our own research and literature sources analysis. Materials and methods. Present work consolidates data from different helminthological works over the past 80 years, supported by our own research results. During the period from 1936 to 2016 different authors examined 1460 specimens of pool frog, using the method of full helminthological autopsy, from 13 regions of the Volga basin. Results. In total 9 nematodes species were recorded. Nematode Icosiella neglecta found for the first time in the studied host from the territory of Russia and Volga basin. Three species appeared to be more widespread: Oswaldocruzia filiformis, Cosmocerca ornata and Icosiella neglecta. For each helminth species the following information included: systematic position, areas of detection, localization, biology, list of definitive hosts, the level of host-specificity. Conclusions. Nematodes of pool frog, excluding I. neglecta, belong to the group of soil-transmitted helminthes (geohelminth) and parasitize in adult stages. Some species (O. filiformis, C. ornata, I. neglecta) are widespread in the host range. -

Subclase Secernentea

Orden Ascaridida T. 21. ASCARIDIDOS. Generalidades y Clasificación. Incluye parásitos con tres labios de gran tamaño. En los machos, cuando existen alas caudales, éstas se localizan Ascaridioideos y Anisakoideos. lateralmente. 1. GENERALIDADES Y CLASIFICACIÓN Los ascarídidos son nematodos con fasmidios (quimiorreceptores posteriores); pertenecen por tanto a la Clase Secernentea. Los machos presentan generalmente alas caudales o bolsas copuladoras. Los ascarídidos de interés veterinario se clasifican en base al siguiente esquema taxonómico: Orden Ascaridida Superfamilia Ascaridoidea Familia Ascarididae Género Ascaris Género Parascaris Género Toxocara Género Toxascaris Fig. 1. Extremo caudal del macho en Ascarididae. Superfamilia Anisakoidea Familia Anisakidae Género Anisakis Superfamilia Ascaridoidea Género Contracaecum Género Phocanema Por lo general son nematodos de gran tamaño. No Género Pseudoterranova presentan cápsula bucal y el esófago carece de bulbo posterior Superfamilia Heterakoidea pronunciado. En algunas especies el esófago está seguido de un Familia Heterakidae: G. Heterakis ventrículo posterior corto que puede derivarse en un apéndice Familia Ascaridiidae: G. Ascaridia 1 ventricular, mientras que otras presentan una prolongación del 2.1. GÉNERO ASCARIS intestino en sentido craneal que se conoce como ciego intestinal (Fig. 12, Familia Anisakidae). Existen dos espículas en los machos Ascaris suum y el ciclo de vida puede ser directo o indirecto. Es un parásito del cerdo con distribución cosmopolita y de 2. FAMILIA ASCARIDIDAE considerable importancia económica. Sin embargo, su prevalencia está disminuyendo debido a los cada vez más frecuentes sistemas Los labios, que como característica del Orden están bien de producción intensiva y a la instauración de tratamientos desarrollados, presentan una serie de papilas labiales externas e antihelmínticos periódicos. Durante años se ha considerado internas, así como un borde denticular en su cara interna. -

Anthelmintic Resistance of Ostertagia Ostertagi and Cooperia Oncophora to Macrocyclic Lactones in Cattle from the Western United States

Veterinary Parasitology 170 (2010) 224–229 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Veterinary Parasitology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vetpar Anthelmintic resistance of Ostertagia ostertagi and Cooperia oncophora to macrocyclic lactones in cattle from the western United States M.D. Edmonds, E.G. Johnson, J.D. Edmonds ∗ Johnson Research LLC, 24007 Highway 20-26, Parma, ID, 83660, USA article info abstract Article history: In June 2008, 122 yearling heifers with a history of anthelmintic resistance were obtained Received 15 October 2009 from pastures in northern California and transported to a dry lot facility in southwest- Received in revised form 28 January 2010 ern Idaho, USA. Fifty heifers with the highest fecal egg counts were selected for study Accepted 24 February 2010 enrollment. Candidates were equally randomized to treatment with either injectable iver- mectin (Ivomec®, Merial, 0.2 mg kg−1 BW), injectable moxidectin (Cydectin®, Fort Dodge, Keywords: 0.2 mg kg−1 BW), oral fenbendazole (Safe-Guard®, Intervet, 5.0 mg kg−1 BW), oral oxfenda- Anthelmintic resistance zole (Synanthic®, Fort Dodge, 4.5 mg kg−1 BW), or saline. At 14 days post-treatment, Cattle Bovine nematodes were recovered from the abomasum, small intestine, and large intestine. Par- Nematodes asitism was confirmed in the control group when 10/10 animals were infected with Efficacy adult Ostertagia ostertagi and 9/10 animals with both developing and early L4 stages of Cooperia O. ostertagi. Similarly, 9/10 animals were parasitized with adult Cooperia spp. Fenbenda- Ostertagia zole and oxfendazole efficacy verses controls were >90% against adult Cooperia spp., while moxidectin caused an 88% parasite reduction post-treatment (P < 0.05). -

Rodentia: Cricetidae) En El Bosque Relicto De Cachil (Provincia Contumazá, Departamento Cajamarca, Perú)

Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Universidad del Perú. Decana de América Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas Escuela Profesional de Ciencias Biológicas Nematofauna del género Thomasomys coues, 1884 (Rodentia: cricetidae) en el bosque relicto de cachil (provincia Contumazá, departamento Cajamarca, Perú) TESIS Para optar el Título Profesional de Biólogo con Mención en Zoología AUTOR María Andrea POLO GONZALES ASESOR Lidia Rosa SANCHEZ PEREZ Lima, Perú 2020 Reconocimiento - No Comercial - Compartir Igual - Sin restricciones adicionales https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Usted puede distribuir, remezclar, retocar, y crear a partir del documento original de modo no comercial, siempre y cuando se dé crédito al autor del documento y se licencien las nuevas creaciones bajo las mismas condiciones. No se permite aplicar términos legales o medidas tecnológicas que restrinjan legalmente a otros a hacer cualquier cosa que permita esta licencia. Referencia bibliográfica Polo, M. (2020). Nematofauna del género Thomasomys coues, 1884 (Rodentia: cricetidae) en el bosque relicto de cachil (provincia Contumazá, departamento Cajamarca, Perú). Tesis para optar el título de Biólogo con Mención en Zoología. Escuela Profesional de Ciencias Biológicas, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Perú. Hoja de metadatos complementarios Código ORCID del autor 0000-0002-5217-151X DNI o pasaporte del autor 73001614 0000-0001-7609-9498 Código ORCID del asesor Código RENACYT: P001097 DNI o pasaporte del asesor 08758229 DIVERSIDAD DE MAMÍFEROS Y SUS PARÁSITOS Y SU IMPLICANCIA EN Grupo de investigación ENFERMEDADES ZOONÓTICAS EMERGENTES Perú Vicerrectorado de Investigación y Posgrado (VRIP) Agencia financiadora Programa de Proyectos de Investigación para Grupos de Investigación B17100921 Perú, Departamento Cajamarca, Provincia Contumazá, Distrito Contumazá, Bosque de Ubicación geográfica donde se Cachil. -

Ancylostoma Ceylanicum

Wei et al. Parasites & Vectors (2016) 9:518 DOI 10.1186/s13071-016-1795-8 RESEARCH Open Access The hookworm Ancylostoma ceylanicum intestinal transcriptome provides a platform for selecting drug and vaccine candidates Junfei Wei1, Ashish Damania1, Xin Gao2, Zhuyun Liu1, Rojelio Mejia1, Makedonka Mitreva2,3, Ulrich Strych1, Maria Elena Bottazzi1,4, Peter J. Hotez1,4 and Bin Zhan1* Abstract Background: The intestine of hookworms contains enzymes and proteins involved in the blood-feeding process of the parasite and is therefore a promising source of possible vaccine antigens. One such antigen, the hemoglobin-digesting intestinal aspartic protease known as Na-APR-1 from the human hookworm Necator americanus, is currently a lead candidate antigen in clinical trials, as is Na-GST-1 a heme-detoxifying glutathione S-transferase. Methods: In order to discover additional hookworm vaccine antigens, messenger RNA was obtained from the intestine of male hookworms, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, maintained in hamsters. RNA-seq was performed using Illumina high-throughput sequencing technology. The genes expressed in the hookworm intestine were compared with those expressed in the whole worm and those genes overexpressed in the parasite intestine transcriptome were further analyzed. Results: Among the lead transcripts identified were genes encoding for proteolytic enzymes including an A. ceylanicum APR-1, but the most common proteases were cysteine-, serine-, and metallo-proteases. Also in abundance were specific transporters of key breakdown metabolites, including amino acids, glucose, lipids, ions and water; detoxifying and heme-binding glutathione S-transferases; a family of cysteine-rich/antigen 5/pathogenesis-related 1 proteins (CAP) previously found in high abundance in parasitic nematodes; C-type lectins; and heat shock proteins. -

Molecular Characterization of Β-Tubulin Isotype-1 Gene of Bunostomum Trigonocephalum

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2018) 7(7): 3351-3358 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 7 Number 07 (2018) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.707.390 Molecular Characterization of β-Tubulin Isotype-1 Gene of Bunostomum trigonocephalum Ravi Kumar Khare1, A. Dixit3, G. Das4, A. Kumar1, K. Rinesh3, D.S. Khare4, D. Bhinsara1, Mohar Singh2, B.C. Parthasarathi2, P. Dipali2, M. Shakya5, J. Jayraw5, D. Chandra2 and M. Sankar1* 1Division of Temperate Animal Husbandry, ICAR- IVRI, Mukteswar, India 2IVRI, Izatnagar, India 3College of Veterinary Science and A.H., Rewa, India 4College of Veterinary Sciences and A.H., Jabalpur, India 5College of Veterinary Sciences and A.H., Mhow, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT The mechanism of benzimidazoles resistance is linked to single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on beta -tubulin isotype-1 gene. The three known SNPs responsible for BZ K e yw or ds resistance are F200Y, F167Y and E198A on the beta-tubulin isotype-1. The present study was aimed to characterize beta-tubulin isotype-1 gene of Bunostomum trigonocephalum, Benzimidazole for identifying variations on possible mutation sites. The adult parasites were collected resistance, Beta from Mukteswar, Uttarakhand. The parasites were thoroughly examined morphologically tubulin, and male parasites were subjected for RNA isolation. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was Bunostomum synthesised from total RNA using OdT. The PCR was performed using cDNA and self trigonocephalum, Small ruminants designed degenerative primers. The purified PCR amplicons were cloned into pGEMT easy vector and custom sequenced. The obtained sequences were analysed using DNA Article Info STAR, MEGA7.0 and Gene tool software.