Download the Education Report (PDF ) 827KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Office of Federal Student Aid As a Performance-Based Organization

The Office of Federal Student Aid as a Performance-Based Organization December 30, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46143 SUMMARY R46143 The Office of Federal Student Aid as a December 30, 2019 Performance-Based Organization Alexandra Hegji The Office of Federal Student Aid (FSA), within the U.S. Department of Education (ED), is Analyst in Social Policy established as a performance-based organization (PBO) pursuant to Section 141 of the Higher Education Act (HEA). FSA is a discrete management unit “responsible for managing the Henry B. Hogue administrative and oversight functions supporting” the HEA Title IV federal student aid Specialist in American programs, including the Pell Grant and the Direct Loan programs. As such, it is the largest National Government provider of postsecondary student financial aid in the nation. In FY2019, FSA oversaw the provision of approximately $130.4 billion in Title IV aid to approximately 11.0 million students attending approximately 6,000 participating institutions of higher education (IHEs). In addition, in FY2019, FSA managed a student loan portfolio encompassing approximately 45 million borrowers with outstanding federal student loans totaling about $1.5 trillion. Among other functions, FSA develops and maintains the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA); obtains funds from the Department of the Treasury to make aid available to students; contracts with numerous third parties to provide goods and services related to Title IV administration, such as student loan servicing; provides oversight of the numerous third parties (e.g., contracted student loan servicers and IHEs) that play a role in administering the Title IV programs; and provides information to third-party stakeholders—such as students, the public, and Congress—regarding Title IV program operations and performance. -

Planning Ahead: Financial Aid for Students with Disabilities 2014 - 2015 Edition

Planning Ahead: Financial Aid for Students with Disabilities 2014 - 2015 Edition HEATH RESOURCE CENTER AT THE NATIONAL YOUTH TRANSITIONS CENTER 2 The HEATH Resource Center at the National Youth Transitions Center Table of Contents ABOUT THIS RESOURCE PAPER 5 WHAT IS FINANCIAL AID? 6 FOUR TYPES OF AID 6 FEDERAL FINANCIAL AID 6 THE HEALTH CARE AND EDUCATIONAL RECONCILIATION ACT OF 2010 8 WHICH APPLICATION DO I COMPLETE? 8 THE DEFENSE OF MARRIAGE ACT (DOMA) & IMPLICATIONS FOR THE TITLE IV STUDENT FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS 9 WHAT IS THE ESTIMATED FAMILY CONTRIBUTION? 9 WHAT IS THE COST OF ATTENDANCE? 10 WHAT IS FINANCIAL NEED? 11 WHAT IS FINANCIAL AID PROCESS? 12 WHAT IS FINANCIAL AID PACKAGE? 13 WHAT EXPENSES ARE DISABILITY RELATED? 14 HOW DOES VOCATIONAL REHABILITATION FIT INTO THE FINANCIAL AID PROCESS? 16 IS THERE A COORDINATION BETWEEN THE VR AGENCIES AND THE FINANCIAL AID OFFICES? 17 STUDENT VETERANS WITH DISABILITIES 18 IS FINANCIAL AID AVAILABLE FOR GRADUATE STUDY? 18 ARE THERE OTHER POSSIBLE SOURCES OF FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE? 19 SUPPLEMENTAL SECURITY INCOME 19 SOCIAL SECURITY BENEFITS 19 TALENT SEARCH, EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES, & SPECIAL SERVICES FOR DISADVANTAGED STUDENTS 20 STATE PROGRAMS 20 PRIVATE SCHOLARSHIPS 20 SCHOLARSHIP SEARCH SERVICES 21 INTERNET SEARCHES 22 FOUNDATION CENTER 23 ALTERNATIVE LOANS 23 SELECTED RESOURCES 24 HEATH Resource Center at the National Youth Transitions Center The George Washington University Email: [email protected] Website: www.heath.gwu.edu 3 The HEATH Resource Center at the National Youth -

Federal Register/Vol. 69, No. 246/Thursday, December 23, 2004

76926 Federal Register / Vol. 69, No. 246 / Thursday, December 23, 2004 / Notices If you use a telecommunications ACTION: Notice of revision of the Federal to take into account inflation. The device for the deaf (TDD), you may call Need Analysis Methodology for the changes are based, in general, upon the Federal Information Relay Service 2005–2006 award year. increases in the Consumer Price Index. (FIRS) at 1–800–877–8339. The Secretary published these adjusted SUMMARY: The Secretary of Education tables in the Federal Register on June Individuals with disabilities may announces the updates to the state tax obtain this document in an alternative 17, 2004. See 69 FR 33890. tables that will be used in the statutory Section 478(g) of part F of the HEA format (e.g., Braille, large print, ‘‘Federal Need Analysis Methodology’’ audiotape, or computer diskette) on further directs the Secretary to update to determine a student’s expected family the tables for State and other taxes after request to the program contact person contribution (EFC) for award year 2005– listed in this section. reviewing the Department of Treasury’s 2006 under part F of title IV of the Statistics of Income file data maintained VIII. Other Information Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA), as by the Internal Revenue Service. The amended (Title IV, HEA Programs). An Secretary delayed publication of these Electronic Access to This Document: EFC is the amount a student and his or tables in order to complete a thorough You may view this document, as well as her family may reasonably be expected review of the available information from all other documents of this Department to contribute toward the student’s the Statistics of Income file data published in the Federal Register, in postsecondary educational costs for maintained by the Internal Revenue text or Adobe Portable Document purposes of determining financial aid Service. -

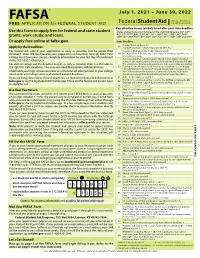

2021-2022 Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA)

FAFSA July 1, 2021 – June 30, 2022 FREE APPLICATION for FEDERAL STUDENT AID Pay attention to any symbols listed after your state deadline. Use this form to apply free for federal and state student States and territories not included in the main listing below: AL, AS*, AZ, CO, FM*, GA, GU*, HI*, KY^$, MH*, NC^$, ND^$, NE, NH*, grants, work-study, and loans. NM, OK^$, PR, PW*, RI*, SD*, VA*, VI*, VT^$*, WA^, WI and WY*. Or apply free online at fafsa.gov. State Deadline Alaska Education Grant ^ $ AK Apply by the Deadlines Alaska Performance Scholarship: June 30, 2021 # $ For federal aid, submit your application as early as possible, but no earlier than Academic Challenge: July 1, 2021 (date received) October 1, 2020. We must receive your application no later than June 30, 2022. Your AR ArFuture Grant: Fall term, July 1, 2021 (date received); spring term, Jan. 10, college must have your correct, complete information by your last day of enrollment 2022 (date received) For many state financial aid programs: March 2, 2021 (date postmarked). in the 2021-2022 school year. Cal Grant also requires submission of a school-certified GPA by March 2, 2021. For state or college aid, the deadline may be as early as October 2020. See the table to For additional community college Cal Grants: Sept. 2, 2021 (date postmarked). the right for state deadlines. You may also need to complete additional forms. CA For noncitizens without a Social Security card or with one issued through the federal Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, fill out Check with your high school counselor or a financial aid administrator at your college the California Dream Act Application. -

The Next Steps: Building a Reimagined System of Student Aid

October 2013 The Next Steps: Building a Reimagined System of Student Aid Beth Akers EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As evidenced by the near-daily media coverage of the affordability crisis in higher education, our system of federal student aid is badly in need of reform. Students are borrowing more than ever before to pay the rapidly rising costs of higher education, while at the same time questioning the value of the degrees they are earning. There are real problems to be solved in our nation’s system of higher education, including: limited access for students from low-income Beth Akers is a fellow in the Brookings households; disappointing graduation rates; students defaulting on loans; and Institution’s Brown rapid tuition inflation across the industry. The first step in creating solutions to Center on Education Policy. She is an expert these problems is to reform the system of financial aid. Recent actions taken on the economics by both the Administration and Congress indicate that they may be prepared of education, with a particular focus to do just that. on higher education finance policy. In preparation for the upcoming reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded a group of organizations, representing a diverse set of viewpoints, to draft reports that provide implementable policy recommendations for reimagining the design and delivery of student financial aid. This project generated a vast number of recommendations for policy makers to consider. Despite the diversity of the viewpoints represented, a number of points of consensus emerged among the reports. While implementation strategies often differed, objectives were aligned. -

Department of Education STUDENT AID OVERVIEW

Department of Education STUDENT AID OVERVIEW Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Request CONTENTS Page Federal Student Aid Programs ................................................................................................O-1 Student Aid Reform Proposals ................................................................................................O-2 Student Aid Programs Output Measures ................................................................................. O-6 Program Performance Information .......................................................................................... O-8 O-0 STUDENT AID OVERVIEW Federal Student Aid Programs (Higher Education Act of 1965, Title IV) (dollars in thousands) FY 2021 Authorization: Indefinite PeriodBudget of fund av ailability: Authority: 2020 2021 Change from Footnot e Appropriation Footnot e Request Footnot e 2020 to 2021 Grants and Work Study: Pell Grants Pell Grant Discretionary funding $22,475,352 $22,475,352 0 1 1 Pell Grant Mandatory funding 7,143,000 7,009,000 -134,000 Subtotal, Pell Grants 29,618,352 29,484,352 -134,000 Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants 865,000 0 -865,000 Federal Work Study 1,180,000 500,000 -680,000 Iraq and Afghanistan Service Grants 463 0 -490 TEACH Grants2 3,2653 27,603 3 24,338 Total, Grants and Work-Study 31,667,080 30,011,955 -1,655,152 Net Loan Subsidy, Loans:4 Federal Family Education Loans (FFEL) 6,394,3645 -466,318 6 -6,860,682 Federal Direct Student Loans 72,164,1437 -8,327,040 -80,491,183 NOTE: Table reflects discretionary and mandatory funding. 1 Amounts appropriated for Pell Grants for 2020 and 2021 include mandatory funding provided in the Higher Education Act, as amended, to fund both the base maximum award and add-on award. 2 TEACH Grants is operated as a credit program. Amounts reflect the new loan subsidy, or the net present value of estimated future costs. -

Federal Student Aid: Additional Actions Needed to Mitigate the Risk

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL Audit Services March 5, 2019 TO: Mark A. Brown Chief Operating Officer Federal Student Aid FROM: Bryon S. Gordon /s/ Assistant Inspector General for Audit SUBJECT: Reissuance of Final Audit Report, “Federal Student Aid: Additional Actions Needed to Mitigate the Risk of Servicer Noncompliance with Requirements for Servicing Federally Held Student Loans,” Control Number ED-OIG/A05Q0008 The attached final audit report, originally issued on February 12, 2019, was reissued on March 5, 2019. After we issued our final audit report on February 12, 2019, we became aware of one instance where a statement made in the report did not reflect supporting audit documentation. We were also provided with additional documentation after the issuance of the audit report that required clarification of a second statement made in the audit report. Once these items were brought to our attention, we conducted a full review of the supporting documentation for the entire report and identified one additional statement that warranted clarification. This review identified no additional issues with the quality of the audit report. We consider these items to be minor corrections. They do not have an effect on our conclusions or recommendations. First, on page 15, we reported: “In 2017, FSA reduced payments to Great Lakes by $1,260, New Hampshire by $37,438, and Oklahoma by $42,550 because the three servicers billed FSA for borrower accounts despite not complying with administrative forbearance requirements.” Although the amounts of the reduced payments are correct, the reason for the reduced payments is not. -

Planning Ahead: Financial Aid for Students with Disabilities 2014 - 2015 Edition

Planning Ahead: Financial Aid for Students with Disabilities 2014 - 2015 Edition HEATH RESOURCE CENTER AT THE NATIONAL YOUTH TRANSITIONS CENTER 2 The HEATH Resource Center at the National Youth Transitions Center Table of Contents ABOUT THIS RESOURCE PAPER 5 WHAT IS FINANCIAL AID? 6 FOUR TYPES OF AID 6 FEDERAL FINANCIAL AID 6 THE HEALTH CARE AND EDUCATIONAL RECONCILIATION ACT OF 2010 8 WHICH APPLICATION DO I COMPLETE? 8 THE DEFENSE OF MARRIAGE ACT (DOMA) & IMPLICATIONS FOR THE TITLE IV STUDENT FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS 9 WHAT IS THE ESTIMATED FAMILY CONTRIBUTION? 9 WHAT IS THE COST OF ATTENDANCE? 10 WHAT IS FINANCIAL NEED? 11 WHAT IS FINANCIAL AID PROCESS? 12 WHAT IS FINANCIAL AID PACKAGE? 13 WHAT EXPENSES ARE DISABILITY RELATED? 14 HOW DOES VOCATIONAL REHABILITATION FIT INTO THE FINANCIAL AID PROCESS? 16 IS THERE A COORDINATION BETWEEN THE VR AGENCIES AND THE FINANCIAL AID OFFICES? 17 STUDENT VETERANS WITH DISABILITIES 18 IS FINANCIAL AID AVAILABLE FOR GRADUATE STUDY? 18 ARE THERE OTHER POSSIBLE SOURCES OF FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE? 19 SUPPLEMENTAL SECURITY INCOME 19 SOCIAL SECURITY BENEFITS 19 TALENT SEARCH, EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES, & SPECIAL SERVICES FOR DISADVANTAGED STUDENTS 20 STATE PROGRAMS 20 PRIVATE SCHOLARSHIPS 20 SCHOLARSHIP SEARCH SERVICES 21 INTERNET SEARCHES 22 FOUNDATION CENTER 23 ALTERNATIVE LOANS 23 SELECTED RESOURCES 24 HEATH Resource Center at the National Youth Transitions Center The George Washington University Email: [email protected] Website: www.heath.gwu.edu 3 The HEATH Resource Center at the National Youth -

FY 2020 Annual Report, Washington, D.C., 20002

ANNUAL REPORT FY 2020 United States Department of Education Betsy DeVos Secretary Federal Student Aid Mark A. Brown Chief Operating Officer Finance Office Alison L. Doone Chief Financial Officer November 16, 2020 This report is in the public domain. Authorization to reproduce it, in whole, or in part, is granted. While permission to reprint this publication is not necessary, the citation should be: U.S. Department of Education, Federal Student Aid, FY 2020 Annual Report, Washington, D.C., 20002. This report is also available under Performance Reports on the Federal Student Aid website at StudentAid.gov. To connect to Federal Student Aid through social media, please visit the Federal Student Aid website at StudentAid.gov or on Twitter at @FAFSA. Federal Student Aid strives to improve and enhance the content quality, report layout, and public accessibility of the Annual Report. Suggestions on how this report can be made more informative and useful are welcome. The public and other stakeholders are encouraged to submit all questions and comments to [email protected]. ii Fiscal Year 2020 Annual Report | Federal Student Aid Contents F Contents About This Report ............................................................. iii About This Report .......................................................................... v Overview of the Federal Student Aid Annual Report .................... vii Management’s Discussion and Analysis (Unaudited) ......... 1 Overview of Management’s Discussion and Analysis ..................... 3 Fiscal Year 2020 -

Draft Strategic Plan

DRAFT DRAFT U.S. Department of Education Betsy DeVos Secretary Federal Student Aid Mark A. Brown Chief Operating Officer This publication is a draft in the public domain. Authorization to reproduce it in whole or in part is not granted. This draft publication is available at Federal Student Aid’s website at https://studentaid.gov/data-center/business-info/strategic-planning-and-reporting DRAFT CONTENTS 05 Letter from the Chief Operating Officer 09 Organization Overview 14 Trends in the Federal Student Aid Environment 15 The size and performance of FSA’s portfolio of loans has direct implications for taxpayers. 21 Students are making high-impact financial decisions without the benefit of adequate financial knowledge. 25 Digital fluency and mobile ubiquity are driving new service expectations among customers. 28 Increased volume of student data has created new opportunities, obligations, and risks. 31 Updating the FSA Mission: Keeping the Promise 39 FSA’s Future Goals and Objectives 40 Empower a High-Performing Organization 44 Provide World-Class Customer Experience to the Students, Parents, and Borrowers We Serve 50 Increase Partner Engagement and Oversight Effectiveness 54 Strengthen Data Protection and Cybersecurity Safeguards 57 Enhance the Management and Transparency of the Portfolio 63 Performance Measures 71 Relationship to the Department of Education Strategic Plan 73 Evaluating Progress 3 DRAFT EMPOWER A HIGH-PERFORMING ORGANIZATION PROVIDE WORLD-CLASS CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE TO THE STUDENTS, PARENTS, AND BORROWERS WE SERVE INCREASE PARTNER ENGAGEMENT AND OVERSIGHT EFFECTIVENESS STRENGTHEN DATA PROTECTION AND CYBERSECURITY SAFEGUARDS ENHANCE THE MANAGEMENT AND TRANSPARENCY OF THE PORTFOLIO 4 DRAFT LETTER FROM THE CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER That’s when, by signing the HEA, President Lyndon B. -

GAO-16-196T, Federal Student Loans: Key Weaknesses Limit Education's Management of Contractors

United States Government Accountability Office Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Government Operations, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform and the Subcommittee on Higher Education and Workforce Training, Committee on Education and the Workforce, House of Representatives For Release on Delivery Expected at 9:00 a.m. ET Wednesday, November 18, 2015 FEDERAL STUDENT LOANS Key Weaknesses Limit Education’s Management of Contractors Statement of Melissa Emrey-Arras, Director Education, Workforce, and Income Security GAO-16-196T November 18, 2015 FEDERAL STUDENT LOANS Key Weaknesses Limit Education’s Management of Contractors Highlights of GAO-16-196T, a testimony before the Subcommittee on Government Operations, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform and the Subcommittee on Higher Education and Workforce Training, Committee on Education and the Workforce, House of Representatives Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found During fiscal year 2014, Education issued The Department of Education’s Office of Federal Student Aid’s (FSA) instructions more than $99 billion in Direct Loans to and guidance to loan servicers are sometimes lacking, resulting in inconsistent 9.4 million borrowers. Education and inefficient services to borrowers. While FSA has taken some steps to contracts with and monitors the improve program instructions and guidance, six of the seven servicers GAO performance of servicers that handle interviewed reported various issues resulting from absent, unclear and billing and other services for borrowers, and entities that support rehabilitation of inconsistent guidance and instructions from FSA. For example, one servicer said defaulted loans. In 1998, federal law there are no instructions for how to apply over- or underpayments to borrower established FSA as a performance-based accounts. -

Counselors and Mentors Handbook on Federal Student Aid U.S

2006–07 COUNSELORS AND MENTORS HANDBOOK ON FEDERAL STUDENT AID U.S. Department of Education A Guide For Those Advising Students About Financial Aid for Postsecondary Education IMPORTANT WEB SITES For You: FSA for Counselors—resources to you help your students www.fsa4schools.ed.gov/counselors • Online training and information about live training • Financial aid PowerPoint presentation and script Federal Student Aid Publications Ordering System www.FSAPubs.org For Your Students: Student Aid on the Web—planning for college, paying for college, and repaying student loans: www.FederalStudentAid.ed.gov • Funding Education Beyond High School: The Guide to Federal Student Aid www.studentaid.ed.gov/guide • Looking for Student Aid www.studentaid.ed.gov/LSA • Fact sheets on various topics www.studentaid.ed.gov/pubs FAFSA on the Web and Federal School Codes www.fafsa.ed.gov PIN information and registration www.pin.ed.gov IMPORTANT TELEPHONE NUMBERS FOR YOU AND YOUR STUDENTS Federal Student Aid Information Center (FSAIC) Toll-free number for questions about federal student aid 1-800-4-FED-AID (1-800-433-3243) TTY (for the hearing impaired) 1-800-730-8913 Toll number for inquirers calling from foreign countries +1-319-337-5665 Inspector General Hotline Reporting student aid fraud (including identity theft), waste, or abuse of U.S. Department of Education funds 1-800-MIS-USED (1-800-647-8733) e-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.ed.gov/misused Want more copies of this book for your colleagues? Call 1-800-394-7084 or visit www.FSAPubs.org. Cover photos: U.S.