T H E C H in E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examination of Estimates of Expenditure 2021-22 Reply Serial No

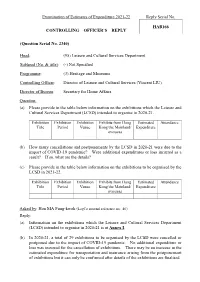

Examination of Estimates of Expenditure 2021-22 Reply Serial No. HAB166 CONTROLLING OFFICER’S REPLY (Question Serial No. 2340) Head: (95) Leisure and Cultural Services Department Subhead (No. & title): (-) Not Specified Programme: (3) Heritage and Museums Controlling Officer: Director of Leisure and Cultural Services (Vincent LIU) Director of Bureau: Secretary for Home Affairs Question: (a) Please provide in the table below information on the exhibitions which the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD) intended to organise in 2020-21. Exhibition Exhibition Exhibition Exhibits from Hong Estimated Attendance Title Period Venue Kong/the Mainland/ Expenditure overseas (b) How many cancellations and postponements by the LCSD in 2020-21 were due to the impact of COVID-19 pandemic? Were additional expenditures or loss incurred as a result? If so, what are the details? (c) Please provide in the table below information on the exhibitions to be organised by the LCSD in 2021-22. Exhibition Exhibition Exhibition Exhibits from Hong Estimated Attendance Title Period Venue Kong/the Mainland/ Expenditure overseas Asked by: Hon MA Fung-kwok (LegCo internal reference no.: 46) Reply: (a) Information on the exhibitions which the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD) intended to organise in 2020-21 is at Annex I. (b) In 2020-21, a total of 29 exhibitions to be organised by the LCSD were cancelled or postponed due to the impact of COVID-19 pandemic. No additional expenditure or loss was incurred for the cancellation of exhibitions. There may be an increase in the estimated expenditure for transportation and insurance arising from the postponement of exhibitions but it can only be confirmed after details of the exhibitions are finalised. -

(WKCD) Development M+ in West Kowloon Cultural District

WKCD-546 Legislative Council Subcommittee on West Kowloon Cultural District (WKCD) Development M+ in West Kowloon Cultural District Purpose This paper seeks to give a full account of the proposal to develop a forward-looking cultural institution with museum functions - M+ as a core arts and cultural facility in the West Kowloon Cultural District (“WKCD”). Background 2. In September 2003, the Government launched the “Invitation for Proposals” (“IFP”) for developing WKCD as a world-class arts, cultural, entertainment and commercial district. The IFP had specified a cluster of four museums with four themes (moving image, modern art, ink and design) commanding a total Net Operating Floor Area (“NOFA”) of at least 75 000 m², and an art exhibition centre as Mandatory Requirements of the project. 3. After the IFP for WKCD was discontinued, the Government appointed the Museums Advisory Group (“MAG”) under the Consultative Committee on Core Arts and Cultural Facilities of WKCD in April 2006 to advise on the need for the four museums previously proposed and their preferred themes, the need to include museums with other themes, the scale and major requirements of each museum and the need for and major specifications of the Art Exhibition Centre. MAG’s deliberations process 4. The MAG conducted a public consultation exercise from mid-May to mid-June 2006 to solicit views on the proposed museum in WKCD. During the period, two open public forums, one focus group meeting and three presentation hearings were held apart from wide publicity arranged through advertisements, radio announcements, press release and invitation letters. 28 written submissions and 30 views were received during the consultation period. -

Caroline Yi Cheng

CAROLINE YI CHENG 1A, Lane 180 Shaanxi Nan Lu Shanghai, 200031, PR China Tel: (8621) 6445 0902 Fax: (8621) 6445 0937 China Mobile: 13818193608 Hong Kong Mobile: 90108613 Email: [email protected] SPECIAL EXHIBITION: 2012 “Spring Blossom” Installations for Van Cleef & Arpels in Paris, Hong Kong, Tokyo SOLO EXHIBITIONS: 2008 “China Blues” The Pottery Workshop Hong Kong 2002 “Glazing China” Grotto Gallery, Hong Kong 1999 “Made in China Blues” The Pottery Workshop, Hong Kong 1995 “Heroine” The Pottery Workshop, Hong Kong 1993 “Seeds of a New Civilization” The Pottery Workshop, Hong Kong 1992 “Made in Hong Kong” Modernology Gallery, San Francisco, USA 1991 “Essence of Goofy Figures” The Pottery Workshop, Hong Kong GROUP EXHIBITIONS: 2013 “New Blue and White” Boston Museum of Fine Arts, USA 2012 “China’s White Gold” Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK “New Site-East Asian Contemporary Ceramics Exhibition” Yingge Ceramics Museum “Chinese Design Today” Themes and Variations Gallery, London, UK “Push Play” NCECA Invitational, Bellevue Art Museum Seattle The Pottery Workshop 25 Years Exhibition, NCECA Seattle “New ‘China’ Porcelain Art from Jingdezhen” The China Institute, New York City, USA Exhibition at the Westerwald Keramik Museum, Hohr-Grenhausen, Germany Korea Ceramic Exhibition, Hanyang University, Seoul New York Asia Week, Dai Ichi Arts “Eighth Ceramic Biennial”, Hangzhou China “Elements – Irish/Chinese Ceramic & Glass Exhibition” Shengling Gallery, Shanghai 2011 “Mirage-Ceramic Experiments with Contemporary Nomads” Duolun Museum of -

Ourhkfoundation Art Book We

About the Authors Introduction: Our Museums the Hidden Gems of Hong Kong 3 CHANG HSIN-KANG (H. K. CHANG) Professor H.K. Chang received and holds one Canadian patent. In his B.S. in Civil Engineering from addition, he has authored 11 books National Taiwan University (1962), in Chinese and 1 book in English, M.S. in Structural Engineering from mainly on education, cultures and Stanford University (1964) and Ph.D. civilizations. His academic interests in Biomedical Engineering from now focus on cultural exchanges Northwestern University (1969). across the Eurasian landmass, particularly along the Silk Road. Having taught at State University of New York at Buffalo (1969-76), McGill Professor Chang is a Foreign Member University (1976-84) and the University of Royal Academy of Engineering of of Southern California (1984-90), he the United Kingdom and a Member of became Founding Dean of School of the International Eurasian Academy Engineering at Hong Kong University of Sciences. of Science and Technology (1990- 94) and then Dean of School of He was named by the Government Engineering at the University of of France to be Chévalier dans l’Ordre Pittsburgh (1994-96). Professor Chang National de la Légion d’Honneur in served as President and University 2000, decorated as Commandeur Professor of City University of Hong dans l’Ordre des Palmes Académiques Kong from 1996 to 2007. in 2009, and was awarded a Gold Bauhinia Star by the Hong Kong SAR In recent years, Professor Chang has Government in 2002. taught general education courses at Tsinghua University, Peking University, Professor Chang served as Chairman China-Europe International Business of the Culture and Heritage School and Bogazici University in Commission of Hong Kong (2000- Istanbul. -

HIA Report for Reprovisioning of Harcourt Road Fresh Water

HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR REPROVISIONING OF HARCOURT ROAD FRESH WATER PUMPING STATION Client: Water Supplies Department Heritage Consultant: February 2014 HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR REPROVISIONING OF HARCOURT ROAD FRESH WATER PUMPING STATION Applicant: Water Supplies Department Heritage Consultant: AGC Design Ltd. Acknowledgements The author of this report would like to acknowledge the following persons, parties, organisations and departments for their assistance and contribution in preparing this report: • Water Supplies Department, The Government of the Hong Kong SAR • Antiquities and Monuments Office • Urbis Limited HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR REPROVISIONING OF HARCOURT ROAD FRESH WATER PUMPING STATION TABLE OF CONTENT List of Figures ............................................................................................................... ii List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................... iv 1.0 INTROUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose of the Report ................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Description of Project ................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Study Area for HIA ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Scope of HIA -

To: Panel [email protected] From: Katty Law Date: 11/09/2014 11

CB(1)2000/13-14(01) To: [email protected] From: Katty Law Date: 11/09/2014 11:38AM Subject: Objection to the proposed pumping station at the Flagstaff House Monument, Hong Kong Park (See attached file: Flagstaff house paper.pdf) (See attached file: Flagstaff House Paper Appendices.pdf) (See attached file: photo2.jpg) (See attached file: photo7.jpg) (See attached file: photo8.jpg) (See attached file: photo29.jpg) (PLEASE CIRCULATE TO ALL MEMBERS OF THE DEVELOPMENT PANEL) Legislative Councillors Members of the Panel on Development Legislative Council Hong Kong Dear Councillors, On behalf of the Central & Western Concern Group and Heritage Watch, I would like to bring to your attention the serious threat posed to the Flagstaff House monument at Hong Kong Park by the proposed repositioning of the Harcourt Road Freshwater pumping station. Our consultant conservation architect Mr Ken Borthwick has written a detailed assessment of this proposed scheme and the paper is attached herewith for your consideration. In his assessment (which closely examines aspects of WSD's HIA) Mr Borthwick looks at the original positioning of Flagstaff House on the crest of the slope, as well as at what he assesses to be its original grounds based on historical plans and early pictures of Flagstaff House in the HIA. He has made an assessment of an historic, rubble stone, fortified defensive wall with loopholes for firing through, which he opines may be the earliest example of British military fortification surviving in Hong Kong and a vital piece of historic evidence. WSD's HIA totally fails to identify this feature for what it is, nor assess its historical and cultural importance. -

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T. Tsang Tai Uk (曾大屋, literally the Big Mansion of the Tsang Family) is also Historical called Shan Ha Wai (山廈圍, literally, Walled Village at the Foothill). Its Interest construction was started in 1847 and completed in 1867. Measuring 45 metres by 137 metres, it was built by Tsang Koon-man (曾貫萬, 1808-1894), nicknamed Tsang Sam-li (曾三利), who was a Hakka (客家) originated from Wuhua (五華) of Guangdong (廣東) province which was famous for producing masons. He came to Hong Kong from Wuhua working as a quarryman at the age of 16 in Cha Kwo Ling (茶果嶺) and Shaukiwan (筲箕灣). He set up his quarry business in Shaukiwan having his shop called Sam Lee Quarry (三利石行). Due to the large demand for building stone when Hong Kong was developed as a city since it became a ceded territory of Britain in 1841, he made huge profit. He bought land in Sha Tin from the Tsangs and built the village. The completed village accommodated around 100 residential units for his family and descendents. It was a shelter of some 500 refugees during the Second World War and the name of Tsang Tai Uk has since been adopted. The sizable and huge fortified village is a typical Hakka three-hall-four-row Architectural (三堂四横) walled village. It is in a Qing (清) vernacular design having a Merit symmetrical layout with the main entrance, entrance hall, middle hall and main hall at the central axis. Two other entrances are to either side of the front wall. -

Finding the Missing Link for the Successful Promotion of Cultural

Public Ecologies of Art Finding the Missing Link for the Successful Promotion of Cultural Tourism in Hong Kong – a Comparative Study of the Hong Kong Museum of Art and the Macau Museum of Art Made in Japan -The Great Odalisque 1964 (Martial Raysse) Yeung May Yee, Mimi On 23 November 2006, the Museums Advisory Group (MAG) of the Consultative Committee on the Core Art and Cultural Facilities of the West Kowloon Cultural District (WKCD) submitted a report on its recommendations on museum facilities in the West Kowloon Cultural District, after having conducted a detailed study of 10 world class museums overseas. The Advisory Group recommended the setting up of a new and forwarding-looking cultural institution in WKCD, whose objectives are to study, promote and showcase the visual culture of the 20th and the 21st centuries from a ‘Hong Kong perspective’ and a ‘now perspective’, coupled with a global vision.1 The institution to be set up 1 Press Release, WKCD Museums Advisory Group makes innovative recommendations, Hong Kong 1 Public Ecologies of Art ‘M+’ (Museum Plus) would consist of four initial broad groupings: ‘Design’, ‘Moving Image’, ‘Popular Culture’ and ‘Visual Art’ (including ink art). M+ will study and showcase visual culture in an unorthodox manner, encourage interaction and pro-actively establish a platform for dialogues with audience. It will also facilitate research and education. Its facilities will include exhibition space, a dedicated outreach and education centre, a library cum archive, bookstore, screening facilities as well as artists-in-residence studios. As one of the four proposed museum themes of M+, namely visual art, overlaps with the main theme of the Hong Kong Museum of Art (HKMA), its establishment will likely compete or even eclipse HKMA in areas like funding, quality of exhibits and patronage. -

Oasis Hong Kong, 1, 31

18_078334 bindex.qxp 1/19/07 11:09 PM Page 302 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Airport Express Line, 33–34 Books, recommended, 37–38 Airport Shuttle, 34 British Airways, 30 Air Tickets Direct, 31 Buddha’s Birthday, 20 AARP, 25 Al’s Diner, 230 Bulldog’s Bar & Grill, 230 Aberdeen, 42, 52, 169 A-Ma, 193 Business hours, 62 restaurants, 154–155 Temple of (Macau), 283–284 Bus travel, 57–58 Accommodations, 70–105. See American Express Macau, 267–268 also Accommodations Index Macau, 268 best, 7–8, 72, 74, 76 offices, 62 Causeway Bay and Wan Chai traveler’s checks, 18 alendar of events, 19–21 expensive, 89–90 C American Foundation for the California, 230 inexpensive, 102–103 Blind, 25 Cantonese food, 115–116 moderate, 95–98 Amusement parks, 174–176 Captain’s Bar, 230–231 very expensive, 82 Antiques and collectibles, Carpets, 211 Central District 10, 208–210 Car travel, 61 expensive, 88–89 Ap Lei Chau, 208 Casa Museu da Taipa, 284–285 very expensive, 79–82 Apliu Street, 215 Casinos, Macau, 286–287 expensive, 82–90 Aqua Spirit, 228 Cathay Pacific Airways, 30, 31 family-friendly, 83 Arch Angel Antiques, 209 Cathay Pacific Holidays, 36 guesthouses and youth Area code, Macau, 268 Cat Street, 42, 194–195 hostels, 103–105 Art, Museum of shopping, 208 inexpensive, 98–103 Hong Kong, 39, 166, 198–199 Cat Street Galleries, 209 Kowloon Macau, 282 Causeway Bay, 52 expensive, 83–88 Art galleries, 210–211 accommodations inexpensive, 98–102 Asian Artefacts (Macau), 287 expensive, 89–90 moderate, 91–94 ATMs (automated -

English Version

Indoor Air Quality Certificate Award Ceremony COS Centre 38/F and 39/F Offices (CIC Headquarters) Millennium City 6 Common Areas Wai Ming Block, Caritas Medical Centre Offices and Public Areas of Whole Building Premises Awarded with “Excellent Class” Certificate (Whole Building) COSCO Tower, Grand Millennium Plaza Public Areas of Whole Building Mira Place Tower A Public Areas of Whole Office Building Wharf T&T Centre 11/F Office (BOC Group Life Assurance Millennium City 5 BEA Tower D • PARK Baby Care Room and Feeding Room on Level 1 Mount One 3/F Function Room and 5/F Clubhouse Company Limited) Modern Terminals Limited - Administration Devon House Public Areas of Whole Building MTR Hung Hom Building Public Areas on G/F and 1/F Wharf T&T Centre Public Areas from 5/F to 17/F Building Dorset House Public Areas of Whole Building Nan Fung Tower Room 1201-1207 (Mandatory Provident Fund Wheelock House Office Floors from 3/F to 24/F Noble Hill Club House EcoPark Administration Building Offices, Reception, Visitor Centre and Seminar Schemes Authority) Wireless Centre Public Areas of Whole Building One Citygate Room Nina Tower Office Areas from 15/F to 38/F World Commerce Centre in Harbour City Public Areas from 5/F to 10/F One Exchange Square Edinburgh Tower Whole Office Building Ocean Centre in Harbour City Public Areas from 5/F to 17/F World Commerce Centre in Harbour City Public Areas from 11/F to 17/F One International Finance Centre Electric Centre 9/F Office Ocean Walk Baby Care Room World Finance Centre - North Tower in Harbour City Public Areas from 5/F to 17/F Sai Kung Outdoor Recreation Centre - Electric Tower Areas Equipped with MVAC System of The Office Tower, Convention Plaza 11/F & 36/F to 39/F (HKTDC) World Finance Centre - South Tower in Harbour City Public Areas from 5/F to 17/F Games Hall Whole Building Olympic House Public Areas of 1/F and 2/F World Tech Centre 16/F (Hong Yip Service Co. -

China Rejuvenated?: Governmentality, Subjectivity, and Normativity the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) China rejuvenated? Governmentality, subjectivity, and normativity: the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games Chong, P.L.G. Publication date 2012 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Chong, P. L. G. (2012). China rejuvenated? Governmentality, subjectivity, and normativity: the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. Iskamp drukkers b.v. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 China Rejuvenated?: Governmentality, Subjectivity, and Normativity The 2008 Beijing Olympic Games © Gladys Pak Lei Chong, 2012 ISBN: 978-94-6191-369-2 Cover design by Yook Koo Printed by Ipskamp Drukkers B.V. The Netherlands China Rejuvenated?: Governmentality, Subjectivity, and Normativity The 2008 Beijing Olympic Games Academisch Proefschrift Ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. -

Discussion Paper for the Third Meeting of the Museums Advisory Group On

WKCD-322 For information MAG/13/2006 on 4 July 2006 Consultative Committee on the Core Arts and Cultural Facilities of the West Kowloon Cultural District Museums Advisory Group Operational and Financial Information on Museums under Leisure and Cultural Services Department Purpose This paper aims to inform Members operational and financial information such as number of visitors, collection items, income and expenditure of museums under the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD). Background 2. At the last meeting held on 15 May 2006, Members requested for information on the number of visitors, existing collection items and financial information of the museums under LCSD in order to facilitate the study of museums facilities in the West Kowloon Cultural District (WKCD). Detailed of these information are summarized below for Member’s reference. Page 1 Number of Visitors 3. In 2005, museums under LCSD organized a total of 118 exhibitions and attracted a record of 4 720 000 visitors. This was due to the fact that the museums had organized more exhibitions and the themes of some of these exhibitions were very popular. For examples, the “Impressionism: Treasures from the National Collection of France” staged at the Hong Kong Museum of Art from 4 February to 10 April 2005 attracted 284 263 visitors. The “Robot Zoo” staged at the Science Museum from 24 June to 25 October 2005 attracted 215 403 visitors. The “From Eastern Han to High Tang: A Journey of Transculturation” from 14 March to 10 June 2005 attracted 296 002 visitors and “The Silk Road: Treasures from Xinjiang” from 21 December 2005 to 19 March 2006 staged at the Heritage Museum attracted 144 761 visitors.