Asides Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Government Inspector by Nikolai Gogol

The Government Inspector (or The Inspector General) By Nikolai Gogol (c.1836) Translated here by Arthur A Sykes 1892. Arthur Sykes died in 1939. All Gogol’s staging instructions have been left in this edition. The names and naming tradition (use of first and family names) have been left as in the original Russian, as have some of the colloquiums and an expected understanding of the intricacies of Russian society and instruments of Government. There are footnotes at the end of each Act. Modern translations tend to use the job titles of the officials, and have updated references to the civil service, dropping all Russian words and replacing them with English equivalents. This script has been provided to demonstrate the play’s structure and flesh out the characters. This is not the final script that will be used in Oxford Theatre Guild’s production in October 2012. Cast of Characters ANTON ANTONOVICH, The Governor or Mayor ANNA ANDREYEVNA, his wife. MARYA ANTONOVNA, his daughter. LUKA LUKICH Khlopov, Director of Schools. Madame Khlopov His wife. AMMOS FYODOROVICH Lyapkin Tyapkin, a Judge. ARTEMI PHILIPPOVICH Zemlyanika, Charity Commissioner and Warden of the Hospital. IVANA KUZMICH Shpyokin, a Postmaster. IVAN ALEXANDROVICH KHLESTAKOV, a Government civil servant OSIP, his servant. Pyotr Ivanovich DOBCHINSKI and Pyotr Ivanovich BOBCHINSKI, [.independent gentleman] Dr Christian Ivanovich HUBNER, a District Doctor. Karobkin - another official Madame Karobkin, his wife UKHAVYORTOV, a Police Superintendent. Police Constable PUGOVKIN ABDULIN, a shopkeeper Another shopkeeper. The Locksmith's Wife. The Sergeant's Wife. MISHKA, servant of the Governor. Waiter at the inn. Act 1 – A room in the Mayor’s house Scene 1 GOVERNOR. -

Repertoire for November 2017

REPERTOIRE FOR NOVEMBER 2017. season MAIN STAGE 2017/18. “RAŠA PLAOVIĆ” STAGE WED. NOV WED. LA BOHEME DUST 01. 19.30 opera by Giacomo Puccini 01. 20.30 comedy by Gyorgy Spiro, the National Th eatre in Belgrade and the Šabac Th eatre NOV THU. WOMEN IN D MINOR/ THE LONG CHRISTMASS DINNER THU. THE MARRIAGE 02. 19.30 one-act ballets; coreography by Radu Poklitaru 02. 20.30comedy by N. Gogol FRI. CAPRICIOUS GIRL FRI. COFFEE WHITE 03. 19.30 comedy by Kosta Trifk ovic 03. 20.30 tragicomedy by Aleksandar Popović SAT. IL TABARRO / SUOR ANGELICA / with guests SAT. THE GLASS MENAGERIE 04. 19.30 оperas by Giacomo Puccini 04. 20.30 drama by Tennessee Williams SUN. THE GREAT DRAMA SUN. THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST 05. 19.30 drama by Siniša Kovačević 05. 20.30 comedy by Oscar Wilde MON. RICHARD THE THIRD MON. SO THAT I SHALL ADMIT TO NOTHING 06. 19.30 drama by William Shakespeare 12.00 06. promotion of Boris Pingović’s poetry TUE. COPPELIA MON. MY PRIZES 07. 19.30 ballet by Léo Delibes 20.30 after Thomas Bernhard’s novel, a project by M.Pelević and S. Beštić, joint production WED. THE GREAT DRAMA TUE. CYRANO 08. 19.30 drama by Siniša Kovačević 07. 20.30 drama by Edmond Rostand THU. FORMAL ACADEMY WED. THE BLACKSMITHS 09. 19.00 on ocasion of the International Day against Fascism and Antisemitism 08. 20.30 comedy by M. Nikolić FRI. DON PASQUALE THU. SMALL MARITAL CRIMES 10. 19.30 opera by Gaetano Donizetti 09. -

264 Zhirinovsky As a Nationalist "Kitsch Artist'' by Sergei Kibalnik

#264 Zhirinovsky as a Nationalist "Kitsch Artist'' by Sergei Kibalnik Sergei Kibalnik is Senior Associate at the fustitute of Russian Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg and a former USIA-Supported Regional Exchange Scholar at the Kennan fustitute for Advanced Russian Studies. The Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars The Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies is a division of the Woodrow WJ.lson International Center for Scholars. Through its programs of residential scholarships, meetings, and publications, the Institute encourages scholarship on Russia and the former Soviet Union, embracing a broad range of fields in the social sciences and humanities. The Kennan Institute is supported by contributions from foundations, corporations, individuals, and the United States Government. Kennan Institute Occasional Papers The Kennan Institute makes Occasional Papers available to all those interested in Russian studies. Occasional Papers are submitted by Kennan Institute scholars and visiting speakers. Copies of Occasional Papers and a list of papers currently available can be obtained free of charge by contacting: Occasional Papers Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies 370 L'Enfant Promenade, SW, Suite 704 Washington, D.C. 20024-2518 (202) 287-3400 This Occasional Paper has been produced with support provided by the Russian, Eurasian, and East European Research and Training Program of the U.S. Department of State (funded by the Soviet and East European Research and Training Act of 1983, or Title VIII). We are most grateful to this sponsor. The views expressed in Kennan Institute Occasional Papers are those of the authors. -

Re-Visiting and Re-Staging

Re-visiting and Re-staging Re-visiting and Re-staging By Anupam Vatsyayan Re-visiting and Re-staging By Anupam Vatsyayan This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Anupam Vatsyayan All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9434-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9434-0 In honour of Mamma & Papa and Maa & Papa For making me and supporting me all the way And to My husband, Vaivasvat Venkat … You mean the world to me We shall not cease from exploration and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started ... and know the place for the first time. —T. S. Eliot CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements .................................................................................... xi Foreword .................................................................................................. xiii Manju Jaidka Preface ....................................................................................................... xv 1. Introduction ............................................................................................ -

The Government Inspector REP Insight

The Government Inspector REP Insight The Government Inspector REP Insight Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Characters in the play ............................................................................................................................. 4 Synopsis .................................................................................................................................................. 5 About the author: Nikolai Gogol ............................................................................................................. 6 Ramps on the Moon & Graeae Theatre Company .................................................................................. 8 Interview with the director: Roxana Silbert ............................................................................................ 9 Production design ................................................................................................................................. 12 Drama activities .................................................................................................................................... 14 English activities .................................................................................................................................... 17 Activities using the text ........................................................................................................................ -

NIKOLAI GOGOL's COMMEDIA DEL DEMONIO by ANN ELIZABETH

NIKOLAI GOGOL'S COMMEDIA DEL DEMONIO by ANN ELIZABETH BORDA B.A., University of British Columbia, 1986 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Slavonic Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1987 © Ann Elizabeth Borda, 1987 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Slavonic Studies The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date 30 0^ 87? ii ABSTRACT Though it is not certain to what extent Gogol was familiar with Dante, it appears he may have regarded Dead Souls I (1842) as the first part of a tripartite scheme in light of La Divina Commedia. Interestingly, the foundations for such a scheme can be found in Gogol's first major publication, Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka (1831-1832) and, in the prose fiction and plays of 1835-1836, a definite pattern is revealed. The pattern that evolved in the works of this period involves the emergence of a demonic element which shatters any illusion of a Paradise which may have been established previously. -

Government Inspector Pdf, Epub, Ebook

GOGOL : GOVERNMENT INSPECTOR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michael Beresford | 100 pages | 01 Jan 1998 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781853994395 | English | London, United Kingdom Gogol : Government Inspector PDF Book The Overcoat. The Government Inspector is the most acclaimed comedy of the season:. China Men by Maxine Hong Kingston. This article was most recently revised and updated by Kathleen Kuiper , Senior Editor. Contos de Sao Petersburgo by Nikolai Gogol. Our Price. Since its premiere in the s, The Government Inspector has been translated and adapted for many different productions, most notably the Chichester Festival in Witty, withering and endlessly entertaining, this is a drama for our times. Topics for Further Study. Khlestakov is 23 years old, skinny and a bit dumb. The first one serves to introduce us to the characters. The play concludes with every character remaining frozen in their surprised and fearful realization that the real inspector general has arrived. Musical Theatre. Petersburg , hoping to enter the civil service , but soon discovered that without money and connections he would have to fight hard for a living. Audition Songs. Petersburg and has been here for two weeks, he is getting into debts and he is not giving a dime for anything. The religious painter Aleksandr Ivanov, who worked in Rome, became his close friend. Search all scenes from plays. By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Notice. The author observed a wide scale of negative social behavior and characteristics. Hlestakov is taken to see the prison, which makes him think he is being arrested for failing to pay his bill at the inn. -

Government Inspector Dramaturgy Program Note

Nikolai Gogol The Government Inspector was written by a strange little man named Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol. Gogol was born in Ukraine on March 19, 1809, which was then apart of the Russian Empire. He was a strong student, but couldn’t keep a job after moving to St. Petersburg following his high school graduation. He then did what was apparently most sensible- he embezzled his mother’s rent money to take a rather aimless tour of Germany. His funds soon ran out, so he returned to St. Petersburg. There he had, and lost, two government jobs and several teaching jobs; this is when his writing began to succeed. His novels and short stories basically started the movement towards realism in Russian literature. His most important works are generally considered Dead Souls and The Overcoat. He also excelled in surrealism, The Nose. Fun fact, The Nose is about a man who wakes up with out his nose, and soon finds out his nose has developed a life of its own, and has surpassed its previous owner in status and rank. After writing Dead Souls, he presumably became depressed, doctors diagnosed him as “Mad”, and he died of a self imposed hunger strike, in an attempt to rid himself of the “devil”. He was 42. Brief Contextual History The Government Inspector was written and takes place in 1830s Russia, in an era were Serfdom was still the societal structure. In this class system, serfs are tenant farmers, basically peasants, who farm a Lord’s land; such a structure kept the gap between class dangerously large. -

Dead Souls Kirill Serebrennikov Nikolaï Gogol

DEAD SOULS Russia in the 1820s: Chichikov is an ordinary but clever man seeking fortune, EN who comes up with the unique idea of buying for next to nothing the deeds / of property of deceased serfs who haven’t been recorded as dead by the administration yet, in order to mortgage them and get a lot more than they are actually worth. Chronicling Chichikov’s negotiations and transactions, Nikolai Gogol created a monumental work that takes the form of a portrait gallery whose triviality, at first amusing, soon turns unsettling. The writer seems to be saying that the worst thing about that story isn’t that the living speculate on the souls of the dead… but that they all turn out to be corrupted by gambling, alcohol, and greed. Using this historic work, which attracted so much hate that his author disowned it, as a springboard, director Kirill Serebrennikov introduces us to the inhabitants of “N.” against a backdrop of plywood, pointing out the flaws of humanity throughout the ages, in Russia and everywhere else. This plywood box is at once a stage for actors who, like puppets, take on the many roles of the novels, and a wretched coffin for those souls whose interests are so morbid they have lost all vitality. With its dark humour and absurd ensemble, this stage is a space-time where human relationships are doomed never to change. KIRILL SEREBRENNIKOV Kirill Serebrennikov was born in 1969 in Rostov, in southeast Russia. Originally destined to a career in physics, in 1992 he found himself celebrating his graduation in the school theatre. -

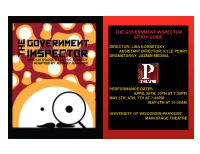

The Government Inspector Study Guide

THE GOVERNMENT INSPECTOR STUDY GUIDE DIRECTOR: LISA KORNETSKY ASSISTANT DIRECTOR: KYLE PERRY DRAMATURGY: JAZMIN MEDINA PERFORMANCE DATES: APRIL 29TH, 30TH AT 7:30PM MAY 5TH, 6TH, 7TH AT 7:30PM MAY 6TH AT 10:00AM UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-PARKSIDE MAIN STAGE THEATRE SYNOPSIS CHARACTERS In a little Russian village in 1836, the townspeople and the ANTON ANTONOVICH SKVOZNIK DUMAKHANOVSKY officials that run it, learn that a government inspector will be coming to town for an undercover inspection. Inevitably, chaos Anton (ahn-tawn) Antonovich (ahn-toe-noff-ich) Skvoznik (shk- ensues as Mayor Antonovich and the other government vost-nic) Dumakhanovsky (doom-mah-kah-noff-skee) officials try to take matters into their own hands by trying to The Mayor is one of the most corrupt officiates of the town who hide and bribe their crooked ways. Eventually, the mayor is has the most to fear from the arrival of the secret government given local gossip that the government inspector is staying at a inspector. Gogol describes him as “a man who has grown old in small inn in the village, and he and the other bumbling officials the state service, who “wears an air of dignified respectability, decide to pay him a visit. Little does the town know that the but is by no means incorruptible.” He too, like me many others, man they visit, Alexandreyevich Hlestakov, is a civil servant indulges in the fantasy of moving up in status by Hlestakov’s running away from his problems and in no way is he a supposed promotion and proposed engagement to his daughter. -

Passion, Imagination, and Madness in Karamzin, Pushkin, and Gogol

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository BURNING FLAMES AND SEETHING BRAINS: PASSION, IMAGINATION, AND MADNESS IN KARAMZIN, PUSHKIN, AND GOGOL BY MATTHEW DAVID MCWILLIAMS THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017 Urbana, Illinois Master’s Committee: Professor Lilya Kaganovsky, Adviser Professor David Cooper Professor John Randolph ABSTRACT My thesis begins with an overview of sensibility (chuvstvitel'nost') and passion (strast') in Russian Sentimentalism, with a focus on the prose fiction of Nikolai Karamzin. After describing the correlation between passion and madness (a commonplace of eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century discourse) and the emergence of a positive Romantic model of madness (featured in the works of E.T.A. Hoffmann and Vladimir Odoevskii, among others), I go on to show that Aleksandr Pushkin and Nikolai Gogol—the most celebrated poet and prose writer of the Romantic era in Russia—both depict madness in a rather un-Romantic light. In the second chapter, I discuss Pushkin’s eclectic treatments of madness, identifying classic tropes of literary madness and several likely sources. I use peripeteia and anagnorisis (concepts from Aristotelian poetics) to address the intersection of madness and plot, and I examine Pushkin’s use of the fantastic in, and the influence of early French psychiatry on, his depictions of madness. The remainder of the text is devoted to three of Gogol’s Petersburg tales, linked by their mad protagonists and the influence of the Künstlerroman: “Nevskii Prospect,” “The Portrait,” and “Diary of a Madman.” I suggest that Piskarev’s story in “Nevskii Prospect” functions as a parody of Karamzin’s fiction, with which it shares a narratorial mode (Dorrit Cohn’s “consonant thought report”). -

The Theme of Apocalypse in Three Works by Gogol' *

Vladimir Glyantz the saCrament oF end The Theme of Apocalypse in Three Works by Gogol’ * Few works by other Russian writers have been as closely connected to their authors' religious views as those of Gogol’. Soviet scholars have often pointed out that The Government Inspector and Dead Souls are, in fact, no more than satires of the Russia of landlords and serfs as it was during the reign of Nikolaj. But academics and soviet theorists have perhaps focused less on the deepest symbolism of Gogol’'s works. One may object that in the first half of the nineteenth century, symbolism had not yet begun to make its mark on Russian literature, and this is certainly the case if we consider it in terms of a dominant literary trend. Historically speaking, however, symbolism dates back more than 100 years. The Christian Church service, for example, is deeply symbolical. The language of symbols was used by Masonic literary authors in their works. In the second half of the seventeenth century, the preacher and church activist Simeon Polockij had already “admitted the rhetorical postulate calling for four levels of meaning to be identified in every text: literal, allegorical, tropological and anagogical.”1 In this article, we will examine the “anagogical” aspects, or, in other words, the symbolic meaning of Gogol’'s texts. For reasons of space, Gogol’'s early works and his later apocalyptic reflections have been omitted. 1. Different Readings of the Various Versions of The Portrait The Portrait was first published in 1835 in the short-story collection “Arabesques.” The main character of the story, a painter, creates a surprising * Translated from russian by olga selivanova and revised by karen turnbull.