The Theme of Apocalypse in Three Works by Gogol' *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The City: the New Jerusalem

Chapter 1 The City: The New Jerusalem “I saw the holy city, the New Jerusalem” (Revelation 21:2). These words from the final book of the Bible set out a vision of heaven that has captivated the Christian imagina- tion. To speak of heaven is to affirm that the human long- ing to see God will one day be fulfilled – that we shall finally be able to gaze upon the face of what Christianity affirms to be the most wondrous sight anyone can hope to behold. One of Israel’s greatest Psalms asks to be granted the privilege of being able to gaze upon “the beauty of the Lord” in the land of the living (Psalm 27:4) – to be able to catch a glimpse of the face of God in the midst of the ambiguities and sorrows of this life. We see God but dimly in this life; yet, as Paul argued in his first letter to the Corinthian Christians, we shall one day see God “face to face” (1 Corinthians 13:12). To see God; to see heaven. From a Christian perspective, the horizons defined by the parameters of our human ex- istence merely limit what we can see; they do not define what there is to be seen. Imprisoned by its history and mortality, humanity has had to content itself with pressing its boundaries to their absolute limits, longing to know what lies beyond them. Can we break through the limits of time and space, and glimpse another realm – another dimension, hidden from us at present, yet which one day we shall encounter, and even enter? Images and the Christian Faith It has often been observed that humanity has the capacity to think. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

The Government Inspector by Nikolai Gogol

The Government Inspector (or The Inspector General) By Nikolai Gogol (c.1836) Translated here by Arthur A Sykes 1892. Arthur Sykes died in 1939. All Gogol’s staging instructions have been left in this edition. The names and naming tradition (use of first and family names) have been left as in the original Russian, as have some of the colloquiums and an expected understanding of the intricacies of Russian society and instruments of Government. There are footnotes at the end of each Act. Modern translations tend to use the job titles of the officials, and have updated references to the civil service, dropping all Russian words and replacing them with English equivalents. This script has been provided to demonstrate the play’s structure and flesh out the characters. This is not the final script that will be used in Oxford Theatre Guild’s production in October 2012. Cast of Characters ANTON ANTONOVICH, The Governor or Mayor ANNA ANDREYEVNA, his wife. MARYA ANTONOVNA, his daughter. LUKA LUKICH Khlopov, Director of Schools. Madame Khlopov His wife. AMMOS FYODOROVICH Lyapkin Tyapkin, a Judge. ARTEMI PHILIPPOVICH Zemlyanika, Charity Commissioner and Warden of the Hospital. IVANA KUZMICH Shpyokin, a Postmaster. IVAN ALEXANDROVICH KHLESTAKOV, a Government civil servant OSIP, his servant. Pyotr Ivanovich DOBCHINSKI and Pyotr Ivanovich BOBCHINSKI, [.independent gentleman] Dr Christian Ivanovich HUBNER, a District Doctor. Karobkin - another official Madame Karobkin, his wife UKHAVYORTOV, a Police Superintendent. Police Constable PUGOVKIN ABDULIN, a shopkeeper Another shopkeeper. The Locksmith's Wife. The Sergeant's Wife. MISHKA, servant of the Governor. Waiter at the inn. Act 1 – A room in the Mayor’s house Scene 1 GOVERNOR. -

Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375) Thomas Franke

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-12-2014 Monsters at the End of Time: Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375) Thomas Franke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Franke, Thomas. "Monsters at the End of Time: Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375)." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/30 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Samuel Franke Candidate History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Michael A. Ryan , Chairperson Timothy C. Graham Sarah Davis-Secord Franke i MONSTERS AT THE END OF TIME: GOG AND MAGOG AND ETHNIC DIFFERENCE IN THE CATALAN ATLAS (1375) by THOMAS FRANKE BACHELOR OF ARTS, UC IRVINE 2012 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico JULY 2014 Franke ii Abstract Franke, Thomas. Monsters at the End of Time: Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375). University of New Mexico, 2014. Although they are only mentioned briefly in Revelation, the destructive Gog and Magog formed an important component of apocalyptic thought for medieval European Christians, who associated Gog and Magog with a number of non-Christian peoples. -

WITH OUR DEMONS a Thesis Submitted By

1 MONSTROSITIES MADE IN THE INTERFACE: THE IDEOLOGICAL RAMIFICATIONS OF ‘PLAYING’ WITH OUR DEMONS A Thesis submitted by Jesse J Warren, BLM Student ID: u1060927 For the award of Master of Arts (Humanities and Communication) 2020 Thesis Certification Page This thesis is entirely the work of Jesse Warren except where otherwise acknowledged. This work is original and has not previously been submitted for any other award, except where acknowledged. Signed by the candidate: __________________________________________________________________ Principal Supervisor: _________________________________________________________________ Abstract Using procedural rhetoric to critique the role of the monster in survival horror video games, this dissertation will discuss the potential for such monsters to embody ideological antagonism in the ‘game’ world which is symptomatic of the desire to simulate the ideological antagonism existing in the ‘real’ world. Survival video games explore ideology by offering a space in which to fantasise about society's fears and desires in which the sum of all fears and object of greatest desire (the monster) is so terrifying as it embodies everything 'other' than acceptable, enculturated social and political behaviour. Video games rely on ideology to create believable game worlds as well as simulate believable behaviours, and in the case of survival horror video games, to simulate fear. This dissertation will critique how the games Alien:Isolation, Until Dawn, and The Walking Dead Season 1 construct and themselves critique representations of the ‘real’ world, specifically the way these games position the player to see the monster as an embodiment of everything wrong and evil in life - everything 'other' than an ideal, peaceful existence, and challenge the player to recognise that the very actions required to combat or survive this force potentially serve as both extensions of existing cultural ideology and harbingers of ideological resistance across two worlds – the ‘real’ and the ‘game’. -

Antichrist As (Anti)Charisma: Reflections on Weber and the ‘Son of Perdition’

Religions 2013, 4, 77–95; doi:10.3390/rel4010077 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article Antichrist as (Anti)Charisma: Reflections on Weber and the ‘Son of Perdition’ Brett Edward Whalen Department of History, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB# 3193, Chapel Hill, NC, 27707, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-919-962-2383 Received: 20 December 2012; in revised form: 25 January 2013 / Accepted: 29 January 2013 / Published: 4 February 2013 Abstract: The figure of Antichrist, linked in recent US apocalyptic thought to President Barack Obama, forms a central component of Christian end-times scenarios, both medieval and modern. Envisioned as a false-messiah, deceptive miracle-worker, and prophet of evil, Antichrist inversely embodies many of the qualities and characteristics associated with Max Weber’s concept of charisma. This essay explores early Christian, medieval, and contemporary depictions of Antichrist and the imagined political circumstances of his reign as manifesting the notion of (anti)charisma, compelling but misleading charismatic political and religious leadership oriented toward damnation rather than redemption. Keywords: apocalypticism; charisma; Weber; antichrist; Bible; US presidency 1. Introduction: Obama, Antichrist, and Weber On 4 November 2012, just two days before the most recent US presidential election, Texas “Megachurch” pastor Robert Jeffress (1956– ) proclaimed that a vote for the incumbent candidate Barack Obama (1961– ) represented a vote for the coming of Antichrist. “President Obama is not the Antichrist,” Jeffress qualified to his listeners, “But what I am saying is this: the course he is choosing to lead our nation is paving the way for the future reign of Antichrist” [1]. -

The Eschatological Sabbath in John's Apocalypse: a Reconsiderationx

Andrews Uniuersity Seminary Studies, Spring 1987, Vol. 25, No. 1, 39-50. Copyright @ 1987 by Andrews University Press. THE ESCHATOLOGICAL SABBATH IN JOHN'S APOCALYPSE: A RECONSIDERATIONX ROBERT M. JOHNSTON Andrews University In the period centering around the first century c.E., the Sabbath rest (meaning principally the seventh day of the week) came in for a great deal of spiritualization and metaph~rization.~This tendency was often conflated with reflection upon the cosmic meaning of the seventh year and the Jubilee year. 1. The Main Directions in Sabbath Sf1ecu2ation The speculation took various directions. One of these was the transcendental Sabbath of Philo-the notion of an endless arche- typical Sabbath, the perfect rest of God in heaven, a rest without toil but not without activity.* This conception partly informs Heb 3:7-4:13,3and possibly to some extent John 5: l7.* "Adapted from a paper presented on Feb. 11, 1986, at Berrien Springs, Michigan, to the annual meeting of the Midwest Section of the Society of Biblical Literature. 'This development obviously did not contradict observance of the literal weekly Sabbath in the case of the Jewish sources, though it was utilized by some early Christian writers, such as Pseudo-Barnabas and Justin, to explain why the observ- ance of the weekly Sabbath rest had been, in their view, superseded. Cf. Willy Rordorf, Sunday: The History of the Day of Rest and Worship in the Earliest Centuries of the Christian Church (Philadelphia, 1968), pp. 47, 89. ZSee, e-g., Philo De Cherubim 87-90; Legum Allegoria 1.5-6. -

A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post-Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism" (2019)

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2019 A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post- Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism Brent Linsley University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Linsley, Brent, "A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post-Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 3341. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3341 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Sense of Unending: Apocalypse and Post-Apocalypse in Novels of Late Capitalism A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Brent Linsley Henderson State University Bachelor of Arts in English, 2000 Henderson State University Master of Liberal Arts in English, 2005 August 2019 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _____________________________________ M. Keith Booker, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________________ ______________________________________ Robert Cochran, Ph.D. Susan Marren, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member Abstract From Frank Kermode to Norman Cohn to John Hall, scholars agree that apocalypse historically has represented times of radical change to social and political systems as older orders are wiped away and replaced by a realignment of respective norms. This paradigm is predicated upon an understanding of apocalypse that emphasizes the rebuilding of communities after catastrophe has occurred. -

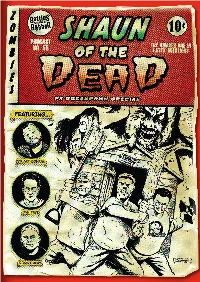

Battleswithbitsofrubber.Com Page 1 CONTENTS

battleswithbitsofrubber.com Page 1 CONTENTS Credits and thanks....................................................................................... Page 3 Foreword by Joe Nazzaro ........................................................................... Page 4 Introduction ................................................................................................. Page 5 Effects in chronological order 1. ‘Haven’t you had your tea?’ ................................................................... Page 6 2. ‘In the garden ... there’s a girl’................................................................ Page 7 3. ‘He’s got an arm off...’ ............................................................................. Page 9 4. ‘Which one do you want? Girl or bloke?’ ........................................... Page 11 5. ‘We take care of Philip.’ .......................................................................... Page 13 6. ‘We’re gonna borrow your car, okay...’ ................................................ Page 13 7. ‘I guess we’ll have to take the Jag.’ ...................................................... Page 14 8. ‘I’ll just flip the mains breakers...’ ........................................................ Page 15 9. ‘I didn’t want to say anything.’.............................................................. Page 16 10. ‘Cock it!’.................................................................................................. Page 17 11. ‘I’m sorry Mum.’ ..................................................................................... -

Gog and Magog. Ezekiel 38-39 As Pre-Text for Revelation 19,17-21 and 20

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament • 2. Reihe Herausgegeben von Martin Hengel und Otfried Hofius 135 Sverre B0e Gog and Magog Ezekiel 38 - 39 as Pre-text for Revelation 19,17-21 and 20,7-10 Mohr Siebeck SVERRE B0E, born 1958; studied theology in Oslo (the Norwegian Lutheran School of Theology), besides other studies in USA (Decorah, Iowa), Germany (Celle), and the University of Oslo. 1981-85 part-time preacher in Vestfold, Norway; 1986-99 teacher at Fjellhaug Mission Seminary, Oslo. 1999 Dr. theol. at the Norwegian Lutheran School of Theology, Oslo. From 1999 Associate Professor at Fjellhaug Mission Seminary, Oslo. Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufhahme B0e, Sverre: Gog and Magog : Ezekiel 38 - 39 as pre-text for Revelation 19,17-21 and 20,7-10 / Sverre B0e. - Tübingen : Mohr Siebeck, 2001 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament : Reihe 2 ; 135) ISBN 3-16-147520-8 © 2001 J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), P.O. Box 2040, D-72101 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to repro- ductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Heinr. Koch in Tübingen. Printed in Germany ISSN 0340-9570 Preface This book is a revised version of my 1999 dissertation with the same title presented to the Norwegian Lutheran School of Theology, Oslo, in 1999. It was prof. Ernst Baasland who introduced me to a scholarly study of the inter-textual relationship between Revelation and Ezekiel. -

THE JAMKARAN HOLY MOSQUE Age Will

THE JAMKARAN HOLY MOSQUE By Rami Yelda Mighty Lord pray to you to hasten the emergence of your last repository the promised one that perfect and pure human being the one that willful this world with justice and peace MahoudAhmadinejad in his address to the UN GeneralAssembly in 2005 These days Irans uranium enrichment ambitions have taken the central stage of the countrys foreign the national level policy On major phenomenon rjZ is taking place the rebuilding of once obscure little Jamkaran Mosque six kilometers east of the holy city of Qom into lavish shrine The news has made significant impact on the Iranian street It is believed that the still living but absent Twelfth Imam saint of Shias the Mahdi or the Wali al-Asr Lord and Master of the Age will re emerge from Sacred Well in this Mosque and transform the world into utopia ofjustice peace and righteousness By now the main differences between the Moslem Sunni majority and the Shia minority are well known to most Beside the debate about Prophet Mohammad succession after his death in AD 632 where according to Shias his cousin Au was cheated from assuming the caliphate there are other doctrinal differences One of the main issues that splits the two sects is that of the Mahdi the Islamic messianic figure The word messiah is derived from the biblical Hebrew word mashiah meaning The Anointed In the Old Testament this term is often used of kings who were anointed with oil The most notable among many is the reference to David who would return someday and conquer the powers of evil by force -

Repertoire for November 2017

REPERTOIRE FOR NOVEMBER 2017. season MAIN STAGE 2017/18. “RAŠA PLAOVIĆ” STAGE WED. NOV WED. LA BOHEME DUST 01. 19.30 opera by Giacomo Puccini 01. 20.30 comedy by Gyorgy Spiro, the National Th eatre in Belgrade and the Šabac Th eatre NOV THU. WOMEN IN D MINOR/ THE LONG CHRISTMASS DINNER THU. THE MARRIAGE 02. 19.30 one-act ballets; coreography by Radu Poklitaru 02. 20.30comedy by N. Gogol FRI. CAPRICIOUS GIRL FRI. COFFEE WHITE 03. 19.30 comedy by Kosta Trifk ovic 03. 20.30 tragicomedy by Aleksandar Popović SAT. IL TABARRO / SUOR ANGELICA / with guests SAT. THE GLASS MENAGERIE 04. 19.30 оperas by Giacomo Puccini 04. 20.30 drama by Tennessee Williams SUN. THE GREAT DRAMA SUN. THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST 05. 19.30 drama by Siniša Kovačević 05. 20.30 comedy by Oscar Wilde MON. RICHARD THE THIRD MON. SO THAT I SHALL ADMIT TO NOTHING 06. 19.30 drama by William Shakespeare 12.00 06. promotion of Boris Pingović’s poetry TUE. COPPELIA MON. MY PRIZES 07. 19.30 ballet by Léo Delibes 20.30 after Thomas Bernhard’s novel, a project by M.Pelević and S. Beštić, joint production WED. THE GREAT DRAMA TUE. CYRANO 08. 19.30 drama by Siniša Kovačević 07. 20.30 drama by Edmond Rostand THU. FORMAL ACADEMY WED. THE BLACKSMITHS 09. 19.00 on ocasion of the International Day against Fascism and Antisemitism 08. 20.30 comedy by M. Nikolić FRI. DON PASQUALE THU. SMALL MARITAL CRIMES 10. 19.30 opera by Gaetano Donizetti 09.