Xxiiird Board Game Studies Colloquium, Paris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woodturning Magazine Index 1

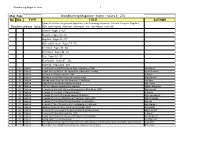

Woodturning Magazine Index 1 Mag Page Woodturning Magazine - Index - Issues 1 - 271 No. No. TYPE TITLE AUTHOR Types of articles are grouped together in the following sequence: Feature, Projects, Regulars, Readers please note: Skills and Projects, Technical, Technique, Test, Test Report, Tool Talk Feature - Pages 1 - 32 Projects - Pages 32 - 56 Regulars - Pages 56 - 57 Skills and Projects - Pages 57 - 70 Technical - Pages 70 - 84 Technique - Pages 84 - 91 Test - Pages 91 - 97 Test Report - Pages 97 - 101 Tool Talk - Pages 101 - 103 1 36 Feature A review of the AWGB's Hay on Wye exhibition in 1990 Bert Marsh 1 38 Feature A light hearted look at the equipment required for turning Frank Sharman 1 28 Feature A review of Raffan's work in 1990 In house 1 30 Feature Making a reasonable living from woodturning Reg Sherwin 1 19 Feature Making bowls from Norfolk Pine with a fine lustre Ron Kent 1 4 Feature Large laminated turned and carved work Ted Hunter 2 59 Feature The first Swedish woodturning seminar Anders Mattsson 2 49 Feature A report on the AAW 4th annual symposium, Gatlinburg, 1990 Dick Gerard 2 40 Feature A review of the work of Stephen Hogbin In house 2 52 Feature A review of the Craft Supplies seminar at Buxton John Haywood 2 2 31 Feature A review of the Irish Woodturners' Seminar, Sligo, 1990 Merryll Saylan 2 24 Feature A review of the Rufford Centre woodturning exhibition Ray Key 2 19 Feature A report of the 1990 instructors' conference in Caithness Reg Sherwin 2 60 Feature Melbourne Wood Show, Melbourne October 1990 Tom Darby 3 58 -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

Bibliography of Traditional Board Games

Bibliography of Traditional Board Games Damian Walker Introduction The object of creating this document was to been very selective, and will include only those provide an easy source of reference for my fu- passing mentions of a game which give us use- ture projects, allowing me to find information ful information not available in the substan- about various traditional board games in the tial accounts (for example, if they are proof of books, papers and periodicals I have access an earlier or later existence of a game than is to. The project began once I had finished mentioned elsewhere). The Traditional Board Game Series of leaflets, The use of this document by myself and published on my web site. Therefore those others has been complicated by the facts that leaflets will not necessarily benefit from infor- a name may have attached itself to more than mation in many of the sources below. one game, and that a game might be known Given the amount of effort this document by more than one name. I have dealt with has taken me, and would take someone else to this by including every name known to my replicate, I have tidied up the presentation a sources, using one name as a \primary name" little, included this introduction and an expla- (for instance, nine mens morris), listing its nation of the \families" of board games I have other names there under the AKA heading, used for classification. and having entries for each synonym refer the My sources are all in English and include a reader to the main entry. -

Inventaire Des Jeux Combinatoires Abstraits

INVENTAIRE DES JEUX COMBINATOIRES ABSTRAITS Ici vous trouverez une liste incomplète des jeux combinatoires abstraits qui sera en perpétuelle évolution. Ils sont classés par ordre alphabétique. Vous avez accès aux règles en cliquant sur leurs noms, si celles-ci sont disponibles. Elles sont parfois en anglais faute de les avoir trouvées en français. Si un jeu vous intéresse, j'ai ajouté une colonne « JOUER EN LIGNE » où le lien vous redirigera vers le site qui me semble le plus fréquenté pour y jouer contre d'autres joueurs. J'ai remarqué 7 catégories de ces jeux selon leur but du jeu respectif. Elles sont décrites ci-dessous et sont précisées pour chaque jeu. Ces catégories sont directement inspirées du livre « Le livre des jeux de pions » de Michel Boutin. Si vous avez des remarques à me faire sur des jeux que j'aurai oubliés ou une mauvaise classification de certains, contactez-moi via mon blog (http://www.papatilleul.fr/). La définition des jeux combinatoires abstraits est disponible ICI. Si certains ne répondent pas à cette définition, merci de me prévenir également. LES CATÉGORIES CAPTURE : Le but du jeu est de capturer ou de bloquer un ou plusieurs pions en particulier. Cette catégorie se caractérise souvent par une hiérarchie entre les pièces. Chacune d'elle a une force et une valeur matérielle propre, résultantes de leur capacité de déplacement. ELIMINATION : Le but est de capturer tous les pions de son adversaire ou un certain nombre. Parfois, il faut capturer ses propres pions. BLOCAGE : Il faut bloquer son adversaire. Autrement dit, si un joueur n'a plus de coup possible à son tour, il perd la partie. -

Havannah and Twixt Are Pspace-Complete

Havannah and TwixT are pspace-complete Édouard Bonnet, Florian Jamain, and Abdallah Saffidine Lamsade, Université Paris-Dauphine, {edouard.bonnet,abdallah.saffidine}@dauphine.fr [email protected] Abstract. Numerous popular abstract strategy games ranging from hex and havannah to lines of action belong to the class of connection games. Still, very few complexity results on such games have been obtained since hex was proved pspace-complete in the early eighties. We study the complexity of two connection games among the most widely played. Namely, we prove that havannah and twixt are pspace- complete. The proof for havannah involves a reduction from generalized geog- raphy and is based solely on ring-threats to represent the input graph. On the other hand, the reduction for twixt builds up on previous work as it is a straightforward encoding of hex. Keywords: Complexity, Connection game, Havannah, TwixT, General- ized Geography, Hex, pspace 1 Introduction A connection game is a kind of abstract strategy game in which players try to make a specific type of connection with their pieces [5]. In many connection games, the goal is to connect two opposite sides of a board. In these games, players take turns placing or/and moving pieces until they connect the two sides of the board. Hex, twixt, and slither are typical examples of this type of game. However, a connection game can also involve completing a loop (havannah) or connecting all the pieces of a color (lines of action). A typical process in studying an abstract strategy game, and in particular a connection game, is to develop an artificial player for it by adapting standard techniques from the game search literature, in particular the classical Alpha-Beta algorithm [1] or the more recent Monte Carlo Tree Search paradigm [6,2]. -

FRW Mstr-Prep-For-PDF Jan 2020

FRW Library Master - January-2020 Page 1 of 109 FRW-ID Artist / Originator Type Title Subject Description AAW-01 AAW Book Amer Woodturner 1987-1992 Techniques and 28 articles compiled from American Woodturner 1987- 1992. Contains projects, techniques and tips that should be of Projects interest to all skill levels. AAW-02 AAW Book Amer Woodturner 1993-1995 Techniques and 38 articles compiled from American Woodturner 1993-1995, 80 pages, black & white. Contains projects, tehniques and Projects tips that should be of interest to all skill levels. AAW-03 AAW Book Amer Woodturner 1996-1998 Techniques and 48 articles compiled from American Woodturner 1996-1998, 112 pages, black & white. Contains projects, techniques Projects and tips that should be of interest to all skill levels. AAW-04 AAW Book Amer Woodturner 1999-2001 Techniques and 44 articles compiled from American Woodturner 1999-2001, 136 pages, black & white.Contains projects, techniques and Projects tips that should be of interest to all skill levels. AAW-05 AAW Book Amer Woodturner 2002-2004 Techniques and 45 articles compiled from American Woodworker 2002-2004, 160 pages, partial color. Contains projects, techniques and Projects tips that should be of interest to all skill levels. AAW-06 AAW CD Amer Woodturner 1986 - 1993 Techniques and A compliation of articles from the AAW Journals of 1986 - 1993. A total of 31 issues.See cover of CD holder for details Projects on reading, locating articles, and printing articles. Must be viewed on a computer. AAW-07 AAW CD Amer Woodturner 1994 - 2001 Techniques and A compliation of articles from the AAW Journals of 1994 - 2001. -

Abstract Games and IQ Puzzles

CZECH OPEN 2019 IX. Festival of abstract games and IQ puzzles Part of 30th International Chess and Games Festival th th rd th Pardubice 11 - 18 and 23 – 27 July 2019 Organizers: International Grandmaster David Kotin in cooperation with AVE-KONTAKT s.r.o. Rules of individual games and other information: http://www.mankala.cz/, http://www.czechopen.net Festival consist of open playing, small tournaments and other activities. We have dozens of abstract games for you to play. Many are from boxed sets while some can be played on our home made boards. We will organize tournaments in any of the games we have available for interested players. This festival will show you the variety, strategy and tactics of many different abstract strategy games including such popular categories as dama variants, chess variants and Mancala games etc while encouraging you to train your brain by playing more than just one favourite game. Hopefully, you will learn how useful it is to learn many new and different ideas which help develop your imagination and creativity. Program: A) Open playing Open playing is playing for fun and is available during the entire festival. You can play daily usually from the late morning to early evening. Participation is free of charge. B) Tournaments We will be very pleased if you participate by playing in one or more of our tournaments. Virtually all of the games on offer are easy to learn yet challenging. For example, try Octi, Oska, Teeko, Borderline etc. Suitable time limit to enable players to record games as needed. -

![[Math.HO] 4 Oct 2007 Computer Analysis of the Two Versions](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3027/math-ho-4-oct-2007-computer-analysis-of-the-two-versions-1983027.webp)

[Math.HO] 4 Oct 2007 Computer Analysis of the Two Versions

Computer analysis of the two versions of Byzantine chess Anatole Khalfine and Ed Troyan University of Geneva, 24 Rue de General-Dufour, Geneva, GE-1211, Academy for Management of Innovations, 16a Novobasmannaya Street, Moscow, 107078 e-mail: [email protected] July 7, 2021 Abstract Byzantine chess is the variant of chess played on the circular board. In the Byzantine Empire of 11-15 CE it was known in two versions: the regular and the symmetric version. The difference between them: in the latter version the white queen is placed on dark square. However, the computer analysis reveals the effect of this ’perturbation’ as well as the basis of the best winning strategy in both versions. arXiv:math/0701598v2 [math.HO] 4 Oct 2007 1 Introduction Byzantine chess [1], invented about 1000 year ago, is one of the most inter- esting variations of the original chess game Shatranj. It was very popular in Byzantium since 10 CE A.D. (and possible created there). Princess Anna Comnena [2] tells that the emperor Alexius Comnenus played ’Zatrikion’ - so Byzantine scholars called this game. Now it is known under the name of Byzantine chess. 1 Zatrikion or Byzantine chess is the first known attempt to play on the circular board instead of rectangular. The board is made up of four concentric rings with 16 squares (spaces) per ring giving a total of 64 - the same as in the standard 8x8 chessboard. It also contains the same pieces as its parent game - most of the pieces having almost the same moves. In other words divide the normal chessboard in two halves and make a closed round strip [1]. -

Chapter 24, Cylindrical, Toroidal, and Spherical Boards

Chapter 24 Cylindrical, toroidal, and spherical boards [The boards in this chapter occupy a half-way house between two-dimensional and three- dimensional boards, being two-dimensional in nature but needing to be bent around in a third dimension if they are to be accurately realised. That said, ‘cylinder chess’ is most often played on a normal 8x8 board, the players imagining the join between the extreme left and right hand files, and the other games in this chapter can be played on planar boards with a greater or lesser degree of imagination.] 24.1 Cylindrical boards Cylinder Chess. Origins unknown: the board whereas in Circular Chess they can only draw was used by the Marquis Teodoro Ciccolini (Variant Chess 48). And of course if the (whose main occupation appears to have been number of files is odd the distinction between the invention of a perpetual motion machine) ‘black’ and ‘white’ bishops vanishes, and a in the early 19th century (feenschach, January- single bishop can reach all squares. March 1980, quoting an article by Adriano A curious endgame situation arises when Chicco in L’Italia Scacchistica, August 1939, White has Ka4, Pa5/b7 (3) against Black Ka7 itself citing Ciccolini’s 1836 book Il Cavallo (1). The winning move in ordinary chess is degli Scacchi). It was later introduced as a 1 a6 to defend the b-pawn, and if 1...Kxa6 problem theme by A. Piccinini in 1907, and then 2 b8(R) (promotion to Q would give has been claimed for others since. The 8x8 stalemate). This doesn’t work in Cylinder board is considered to be wrapped round a Chess because K+R v K is not a win, but now vertical cylinder so that 4les a and h are 1 a6 Kxa6 2 b8(Q) wins because there is no contiguous. -

Math-GAMES IO1 EN.Pdf

Math-GAMES Compendium GAMES AND MATHEMATICS IN EDUCATION FOR ADULTS COMPENDIUMS, GUIDELINES AND COURSES FOR NUMERACY LEARNING METHODS BASED ON GAMES ENGLISH ERASMUS+ PROJECT NO.: 2015-1-DE02-KA204-002260 2015 - 2018 www.math-games.eu ISBN 978-3-89697-800-4 1 The complete output of the project Math GAMES consists of the here present Compendium and a Guidebook, a Teacher Training Course and Seminar and an Evaluation Report, mostly translated into nine European languages. You can download all from the website www.math-games.eu ©2018 Erasmus+ Math-GAMES Project No. 2015-1-DE02-KA204-002260 Disclaimer: "The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein." This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ISBN 978-3-89697-800-4 2 PRELIMINARY REMARKS CONTRIBUTION FOR THE PREPARATION OF THIS COMPENDIUM The Guidebook is the outcome of the collaborative work of all the Partners for the development of the European Erasmus+ Math-GAMES Project, namely the following: 1. Volkshochschule Schrobenhausen e. V., Co-ordinating Organization, Germany (Roland Schneidt, Christl Schneidt, Heinrich Hausknecht, Benno Bickel, Renate Ament, Inge Spielberger, Jill Franz, Siegfried Franz), reponsible for the elaboration of the games 1.1 to 1.8 and 10.1. to 10.3 2. KRUG Art Movement, Kardzhali, Bulgaria (Radost Nikolaeva-Cohen, Galina Dimova, Deyana Kostova, Ivana Gacheva, Emil Robert), reponsible for the elaboration of the games 2.1 to 2.3 3. -

Chapter 7 Some Francois Andre Danican Philidor Websites

CHAPTER 7 SOME FRANCOIS ANDRE DANICAN PHILIDOR WEBSITES It seems websites move around and disappear since this was transcribed in early 2017. François-André Danican Philidor - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/François-André_Danican_Philidor The first site is the Wikipedia site and contains much valuable genealogical information As given: 1.Jean Danican Philidor (1620-1679) was P’s grandfather. A musician with the Grande Ecurie. The Original name was Danican and earlier a Scottish origin with the name Duncan. Jean was nicknamed by Louis XIII because his oboe playing reminded the King of an Italian virtuoso oboist from Siena named Filidori. 2.Michael Danican (d.1659) Great Uncle of P oboist and with Ms. Hottetere modified the oboe so that the reed was held by the player’s lips. 3.Andrei Danican Philidor (1647-1730) P’s father known as ‘P the Elder’,oboist and crumhorn player. Member of the Grande Ecurie Military Band and later performed at the Court Royal Chapel under Louis XIV. 4. Jacques Danican Philidor (1657-1708) P’s father’s younger brother and known as ‘P the younger’. 5. Pierre Danican Philidor (1681-1731) Son of Jacques and a musician. 6.Andre Danican Philidor (1681-1728) Older brother of P. Founded the Concert Spirituel a public concert held in the Tuileries Palace 1725-1791. P. was born to his father’s second wife Elizabeth Roy whom he had wed in 1719 when she was 19 years old and he 72 and 79 when P. was born and he died 4 years later. Career:- P joined the Royal Choir of Louis XV in 1732 when 6 and had his first composition at 11. -

![Arxiv:1605.04715V1 [Cs.CC] 16 May 2016 of Hex Has Acquired a Special Spot in the Heart of Abstract Game Aficionados](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7601/arxiv-1605-04715v1-cs-cc-16-may-2016-of-hex-has-acquired-a-special-spot-in-the-heart-of-abstract-game-a-cionados-2547601.webp)

Arxiv:1605.04715V1 [Cs.CC] 16 May 2016 of Hex Has Acquired a Special Spot in the Heart of Abstract Game Aficionados

On the Complexity of Connection Games Edouard´ Bonnet [email protected] Sztaki, Hungarian Academy of Sciences Florian Jamain [email protected] Lamsade, Universit´eParis-Dauphine Abdallah Saffidine [email protected] Cse, The University of New South Wales Abstract In this paper, we study three connection games among the most widely played: havannah, twixt, and slither. We show that determining the outcome of an arbitrary input position is PSPACE-complete in all three cases. Our reductions are based on the popular graph problem generalized geography and on hex itself. We also consider the complexity of generalizations of hex parameterized by the length of the solution and establish that while short generalized hex is W[1]-hard, short hex is FPT. Finally, we prove that the ultra-weak solution to the empty starting position in hex cannot be fully adapted to any of these three games. Keywords: Complexity, Havannah, Twixt, Hex, Slither, PSPACE 1. Introduction Since its independent inventions in 1942 and 1948 by the poet and mathe- matician Piet Hein and the economist and mathematician John Nash, the game arXiv:1605.04715v1 [cs.CC] 16 May 2016 of hex has acquired a special spot in the heart of abstract game aficionados. Its purity and depth has lead Jack van Rijswijck to conclude his PhD thesis with the following hyperbole [1]. Hex has a Platonic existence, independent of human thought. If ever we find an extraterrestrial civilization at all, they will know hex, without any doubt. Hex not only exerts a fascination on players, but it is the root of the field of connection games which is being actively explored by game designers and researchers alike [2].