Exploring Leopard with Dtrace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kutrace: Where Have All the Nanoseconds Gone?

KUTrace: Where have all the nanoseconds gone? Richard Sites, Invited Professor EPFL 2017.10.27 Tracing Summit 2017, Prague Richard Sites 2017.10.27 Outline Observability problem statement KUTrace solution Tracing design goals Goals drive the design Results Display Design Comparisons Conclusions Richard Sites 2017.10.27 Observability problem statement Richard Sites 2017.10.27 3 Problem statement This talk is about tail latency in real user-facing datacenter transactions. It is not about batch processing throughput, nor about benchmarks. Context: A datacenter of perhaps 20,000 servers running software services that spread work for a user-facing transaction across a few hundred or thousand machines in parallel. Each server handles hundreds of transactions per second. Some transactions are unusually slow, but not repeatably. Slow transactions occur unpredictably, but there are several per minute. We wish to observe where all the time goes in such transactions, and observe why they are slow. Richard Sites 2017.10.27 Problem statement ☞ Some transactions are unusually slow, but not repeatably. ∴ There is some source of interference just before or during a slow transaction. Understanding tail latency requires complete traces of CPU events over a few minutes, with small enough CPU and memory overhead to be usable under busiest-hour live load. Existing tracing tools have much-too-high overhead. Problem: build better tail-latency observation tools Richard Sites 2017.10.27 KUTrace solution Richard Sites 2017.10.27 6 KUTrace solution KUTrace uses minimal Linux kernel patches on a single server to trace every transition between kernel- and user-mode execution, on every CPU core, with small enough overhead to use routinely on live loads. -

Debugging Kernel Problems

Debugging Kernel Problems by GregLehey Edition for AsiaBSDCon 2004 Taipei, 13 March 2004 Debugging Kernel Problems by GregLehey([email protected]) Copyright © 1995-2004 GregLehey 3Debugging Kernel Problems Preface Debugging kernel problems is a black art. Not manypeople do it, and documentation is rare, in- accurate and incomplete. This document is no exception: faced with the choice of accuracyand completeness, I chose to attempt the latter.Asusual, time was the limiting factor,and this draft is still in beta status. This is a typical situation for the whole topic of kernel debugging: building debug tools and documentation is expensive,and the people who write them are also the people who use them, so there'satendencytobuild as much of the tool as necessary to do the job at hand. If the tool is well-written, it will be reusable by the next person who looks at a particular area; if not, it might fall into disuse. Consider this book a starting point for your own develop- ment of debugging tools, and remember: more than anywhere else, this is an area with ``some as- sembly required''. Debugging Kernel Problems 4 1 Introduction Operating systems fail. All operating systems contain bugs, and theywill sometimes cause the system to behave incorrectly.The BSD kernels are no exception. Compared to most other oper- ating systems, both free and commercial, the BSD kernels offer a large number of debugging tools. This tutorial examines the options available both to the experienced end user and also to the developer. In this tutorial, we’ll look at the following topics: • Howand whykernels fail. -

Chapter 1. Origins of Mac OS X

1 Chapter 1. Origins of Mac OS X "Most ideas come from previous ideas." Alan Curtis Kay The Mac OS X operating system represents a rather successful coming together of paradigms, ideologies, and technologies that have often resisted each other in the past. A good example is the cordial relationship that exists between the command-line and graphical interfaces in Mac OS X. The system is a result of the trials and tribulations of Apple and NeXT, as well as their user and developer communities. Mac OS X exemplifies how a capable system can result from the direct or indirect efforts of corporations, academic and research communities, the Open Source and Free Software movements, and, of course, individuals. Apple has been around since 1976, and many accounts of its history have been told. If the story of Apple as a company is fascinating, so is the technical history of Apple's operating systems. In this chapter,[1] we will trace the history of Mac OS X, discussing several technologies whose confluence eventually led to the modern-day Apple operating system. [1] This book's accompanying web site (www.osxbook.com) provides a more detailed technical history of all of Apple's operating systems. 1 2 2 1 1.1. Apple's Quest for the[2] Operating System [2] Whereas the word "the" is used here to designate prominence and desirability, it is an interesting coincidence that "THE" was the name of a multiprogramming system described by Edsger W. Dijkstra in a 1968 paper. It was March 1988. The Macintosh had been around for four years. -

Optimization of System's Performance with Kernel Tracing by Cohort Intelligence

I.J. Information Technology and Computer Science, 2017, 6, 59-66 Published Online June 2017 in MECS (http://www.mecs-press.org/) DOI: 10.5815/ijitcs.2017.06.08 Optimization of System’s Performance with Kernel Tracing by Cohort Intelligence Aniket B. Tate Dept. of Computer Engineering, Vishwakarma Institute of Information Technology, Pune, 411048, India E-mail: [email protected] Laxmi A. Bewoor Dept. of Computer Engineering, Vishwakarma Institute of Information Technology, Pune, 411048, India E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—Linux tracing tools are used to record the execution time etc. which shows better results. While events running in the background on the system. But scheduling a process on one of the cores, the scheduler these tools lack to analyze the log data. In the field of considers the average waiting time, turnaround time, time Artificial Intelligence Cohort Intelligence (CI) is recently quantum for a process, number of context switches, proposed technique, which works on the principle of self- earliness, the tardiness of process etc. But the scheduler learning within a cohort. This paper presents an approach does not take CPU load into consideration. As a result of to optimize the performance of the system by tracing the this, the cores get unevenly loaded and many of the cores system, then extract the information from trace data and will be kept in ideal state. Cohort Intelligence (CI) is pass it to cohort intelligence algorithm. The output of recently introduced meta-heuristics [6][7] it works on cohort intelligence algorithm shows, how the load of the self-supervised learning behavior in a cohort. -

BSD UNIX Toolbox 1000+ Commands for Freebsd, Openbsd

76034ffirs.qxd:Toolbox 4/2/08 12:50 PM Page iii BSD UNIX® TOOLBOX 1000+ Commands for FreeBSD®, OpenBSD, and NetBSD®Power Users Christopher Negus François Caen 76034ffirs.qxd:Toolbox 4/2/08 12:50 PM Page ii 76034ffirs.qxd:Toolbox 4/2/08 12:50 PM Page i BSD UNIX® TOOLBOX 76034ffirs.qxd:Toolbox 4/2/08 12:50 PM Page ii 76034ffirs.qxd:Toolbox 4/2/08 12:50 PM Page iii BSD UNIX® TOOLBOX 1000+ Commands for FreeBSD®, OpenBSD, and NetBSD®Power Users Christopher Negus François Caen 76034ffirs.qxd:Toolbox 4/2/08 12:50 PM Page iv BSD UNIX® Toolbox: 1000+ Commands for FreeBSD®, OpenBSD, and NetBSD® Power Users Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 10475 Crosspoint Boulevard Indianapolis, IN 46256 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2008 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada ISBN: 978-0-470-37603-4 Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the publisher. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permis- sion should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, (317) 572-3447, fax (317) 572-4355, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. -

Absolute BSD—The Ultimate Guide to Freebsd Table of Contents Absolute BSD—The Ultimate Guide to Freebsd

Absolute BSD—The Ultimate Guide to FreeBSD Table of Contents Absolute BSD—The Ultimate Guide to FreeBSD............................................................................1 Dedication..........................................................................................................................................3 Foreword............................................................................................................................................4 Introduction........................................................................................................................................5 What Is FreeBSD?...................................................................................................................5 How Did FreeBSD Get Here?..................................................................................................5 The BSD License: BSD Goes Public.......................................................................................6 The Birth of Modern FreeBSD.................................................................................................6 FreeBSD Development............................................................................................................7 Committers.........................................................................................................................7 Contributors........................................................................................................................8 Users..................................................................................................................................8 -

Proceedings of the Linux Symposium

Proceedings of the Linux Symposium Volume One June 27th–30th, 2007 Ottawa, Ontario Canada Contents The Price of Safety: Evaluating IOMMU Performance 9 Ben-Yehuda, Xenidis, Mostrows, Rister, Bruemmer, Van Doorn Linux on Cell Broadband Engine status update 21 Arnd Bergmann Linux Kernel Debugging on Google-sized clusters 29 M. Bligh, M. Desnoyers, & R. Schultz Ltrace Internals 41 Rodrigo Rubira Branco Evaluating effects of cache memory compression on embedded systems 53 Anderson Briglia, Allan Bezerra, Leonid Moiseichuk, & Nitin Gupta ACPI in Linux – Myths vs. Reality 65 Len Brown Cool Hand Linux – Handheld Thermal Extensions 75 Len Brown Asynchronous System Calls 81 Zach Brown Frysk 1, Kernel 0? 87 Andrew Cagney Keeping Kernel Performance from Regressions 93 T. Chen, L. Ananiev, and A. Tikhonov Breaking the Chains—Using LinuxBIOS to Liberate Embedded x86 Processors 103 J. Crouse, M. Jones, & R. Minnich GANESHA, a multi-usage with large cache NFSv4 server 113 P. Deniel, T. Leibovici, & J.-C. Lafoucrière Why Virtualization Fragmentation Sucks 125 Justin M. Forbes A New Network File System is Born: Comparison of SMB2, CIFS, and NFS 131 Steven French Supporting the Allocation of Large Contiguous Regions of Memory 141 Mel Gorman Kernel Scalability—Expanding the Horizon Beyond Fine Grain Locks 153 Corey Gough, Suresh Siddha, & Ken Chen Kdump: Smarter, Easier, Trustier 167 Vivek Goyal Using KVM to run Xen guests without Xen 179 R.A. Harper, A.N. Aliguori & M.D. Day Djprobe—Kernel probing with the smallest overhead 189 M. Hiramatsu and S. Oshima Desktop integration of Bluetooth 201 Marcel Holtmann How virtualization makes power management different 205 Yu Ke Ptrace, Utrace, Uprobes: Lightweight, Dynamic Tracing of User Apps 215 J. -

Mac OS X Enterprise Application Management Best Practices Macosxlabs.Org

Mac OS X Enterprise Application Management Best Practices macosxlabs.org Richard Glaser, University of Utah Philip Rinehart, Yale University June 21, 2004 Contents 1 Abstract 1 1.1 Preface . 1 1.2 Audience . 2 1.3 Factors in the enterprise . 3 1.4 Comments and Questions . 4 2 Serialization of applications 4 2.0.1 Network Detection . 5 2.0.2 Server metering . 5 2.1 Hardware serialization . 7 2.1.1 Hardware Locks . 7 2.1.2 Media verification . 9 2.1.3 Challenge/Response . 9 3 Security 10 3.1 Permissions and File Modes . 11 3.1.1 SUID . 11 3.1.2 World writable directories . 13 3.2 Unnecessary open ports . 14 3.3 Startup items and root daemons . 14 3.4 Tripwire . 14 4 Installation 16 4.1 Log Files . 17 4.2 Administrative or root rights . 17 4.3 Non-standard location . 17 4.4 Broken links . 18 4.5 Path limitations . 19 4.5.1 File name limitation . 19 4.5.2 Directory location limitations . 19 ii 5 Missing Support and Features 19 5.1 Legacy application support . 20 5.2 Human Resources software . 20 5.3 Web-based instructional software . 21 5.4 Geographic Information Systems Support . 21 5.5 Backup software . 21 5.6 Lack of any Mac OS X alternative . 21 6 Distribution issues 22 6.1 Network Home Directories . 24 6.2 Resource forks . 25 6.3 Non-standard serialization . 25 6.4 Scratch space management . 26 6.5 ByHost preferences . 26 6.6 Auto launched application preferences . 26 6.7 File Attributes . -

Mac OS X Technology Overview

Mac OS X Technology Overview 2006-06-28 Finder, Safari, Spotlight, Tiger, and Xserve Apple Inc. are trademarks of Apple Inc. © 2004, 2006 Apple Computer, Inc. Adobe, Acrobat, and PostScript are All rights reserved. trademarks or registered trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the U.S. No part of this publication may be and/or other countries. reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, Intel and Intel Core are registered mechanical, electronic, photocopying, trademarks of Intel Corportation or its recording, or otherwise, without prior subsidiaries in the United States and other written permission of Apple Inc., with the countries. following exceptions: Any person is hereby Java and all Java-based trademarks are authorized to store documentation on a trademarks or registered trademarks of Sun single computer for personal use only and Microsystems, Inc. in the U.S. and other to print copies of documentation for countries. personal use provided that the OpenGL is a registered trademark of Silicon documentation contains Apple’s copyright Graphics, Inc. notice. PowerPC and and the PowerPC logo are The Apple logo is a trademark of Apple Inc. trademarks of International Business Use of the “keyboard” Apple logo Machines Corporation, used under license (Option-Shift-K) for commercial purposes therefrom. without the prior written consent of Apple UNIX is a registered trademark of The Open may constitute trademark infringement and Group unfair competition in violation of federal and state laws. Simultaneously published in the United States and Canada. No licenses, express or implied, are granted with respect to any of the technology Even though Apple has reviewed this document, APPLE MAKES NO WARRANTY OR described in this document. -

The Process Model (2) L41 Lecture 4 Dr Robert N

11/14/17 The Process Model (2) L41 Lecture 4 Dr Robert N. M. Watson 15 November 2017 Reminder: last time • The process model and its evolution • Isolation via virtual addressing and rings • Controlled transition to kernel via traps • Controlled communication to other processes intitiated via the kernel • Brutal (re,pre)-introduction to virtual memory • Where processes come from: the process life cycle, ELF and run-time linking L41 Lecture 4 - The Process Model (2) 2 1 11/14/17 This time: the process model (2) • More on traps and system calls • Synchrony and asynchrony • Security and reliability • Kernel work in system calls and traps • Virtual memory support for the process model • Readings for next time L41 Lecture 4 - The Process Model (2) 3 System calls • User processes request kernel services via system calls: • Traps that model function-call semantics; e.g., • open() opens a file and returns a file descriptor • fork() creates a new process • System calls appear to be library functions (e.g., libc) 1. Function triggers trap to transfer control to the kernel 2. System-call arguments copied into kernel 3. Kernel implements service 4. System-call return values copied out of kernel 5. Kernel returns from trap to next user instruction • Some quirks relative to normal APIs; e.g., • C return values via normal ABI calling convention… • ... But also per-thread errno to report error conditions • ... EINTR: for some calls, work got interrupted, try again L41 Lecture 4 - The Process Model (2) 4 2 11/14/17 System-call synchrony • Most syscalls behave like synchronous C functions • Calls with arguments (by value or by reference) • Return values (an integer/pointer or by reference) • Caller regains control when the work is complete; e.g., • getpid() retrieves the process ID via a return value • read() reads data from a file: on return, data in buffer • Except . -

Rosetta Stone for Unix

This custom drawing feature now works in both Mozilla and in IE 5 or better for Solaris, HP-UX, or Windows. Use click, shift-click, control-click, and the "set" and "clear" buttons to select the desired subset of OSs. Then select "Draw table" to launch a new window with your custom table. Thanks to Mårten Svantesson <[email protected]> for the improved JavaScript. A Sysadmin's Unixersal Translator (ROSETTA STONE) OR What do they call that in this world? Contributions and corrections gratefully accepted. Please help us fill in the blanks. New "tasks" are welcome, too! PDF version (for best results print US legal size, landscape orientation. If your browser plug-in has trouble with the PDF, then download it and load it in stand-alone acroread). Framed version. Based on Pat Wilson's version. OS versions in parentheses; e.g. 10+ means version 10 and greater; 9- means version 9 and previous. $=extra cost If not specified, commands are in one of the following directories: /usr/bin, /usr/sbin, /sbin, /bin Categories: hardware, firmware, devices disks kernel, boot, swap files, volumes networking security, backup software, patching, tracing, logging references TASK \ OS AIX Darwin DG/UX FreeBSD HP-UX IRIX Linux NetBSD OpenBSD Reliant SCO UnixWare Solaris SunOS 4 Tru64 Ultrix UNICOS OS / TASK Cray Inc., formed SCO UnixWare 7.0.1& The Open Source Fujitsu Siemens. Based from the March SCO UnixWare 7.1.1 Solaris 2.0-2.6, 7, 8, 9 (Digital Unix, OSF/1) foundation for Mac OS (rh) = Red Hat, on DC/OSX from Solaris 1.* 2000 merger of OS notes SVR4-based Mandrake, Suse,.. -

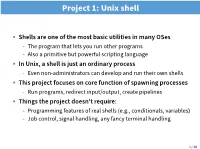

Project 1: Unix Shell

Project 1: Unix shell • Shells are one of the most basic utilities in many OSes - The program that lets you run other programs - Also a primitive but powerful scripting language • In Unix, a shell is just an ordinary process - Even non-administrators can develop and run their own shells • This project focuses on core function of spawning processes - Run programs, redirect input/output, create pipelines • Things the project doesn’t require: - Programming features of real shells (e.g., conditionals, variables) - Job control, signal handling, any fancy terminal handling 1 / 18 UNIX file system calls • System calls are requests from processes to the OS kernel - The kernel (e.g., linux) is a program run in a privileged CPU mode - syscall ≈ library call to a function with greater hardware access • Original UNIX paper is a great reference on core system calls • Applications “open” files (or devices) by name - I/O happens through open files • int open(char *path, int flags, /*int mode*/...); - flags: O_RDONLY, O_WRONLY, O_RDWR - O_CREAT: create the file if non-existent - O_EXCL: (w. O_CREAT) create if file exists already - O_TRUNC: Truncate the file - O_APPEND: Start writing from end of file - mode: final argument with O_CREAT • Returns file descriptor—used for all I/O to file 2 / 18 Error returns • What if open fails? Returns -1 (invalid fd) • Most system calls return -1 on failure - Specific kind of error in global int errno - In retrospect, bad design decision for threads/modularity • #include <sys/errno.h> for possible values - 2 = ENOENT “No such file