Community Involvement for Health Promotion in Ferghana Oblast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing for Integrated Rural Development Improvement Program

i Due Diligence Report on Environment and Social Safeguards Final Report June 2015 UZB: Housing for Integrated Rural Development Investment Program Prepared by: Project Implementation Unit under the Ministry of Economy for the Republic of Uzbekistan and The Asian Development Bank ii ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DDR Due Diligence Review EIA Environmental Impact Assessment Housing for Integrated Rural Development HIRD Investment Program State committee for land resources, geodesy, SCLRGCSC cartography and state cadastre SCAC State committee of architecture and construction NPC Nature Protection Committee MAWR Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources QQL Qishloq Qurilish Loyiha QQI Qishloq Qurilish Invest This Due Diligence Report on Environmental and Social Safeguards is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 4 B. SUMMARY FINDINGS ............................................................................................... 4 C. SAFEGUARD STANDARDS ...................................................................................... -

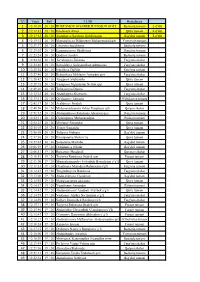

T/R 1 1-O'rin 2 2-O'rin 3 3-O'rin 4 5 6 7

T/r Vaqti Ball F.I.SH Hududingiz 1 12:10:05 20 / 20 RUSTAMOV OG'ABEK ILYOSJON OG'LI Beshariq tumani 1-o'rin 2 12:12:43 20 / 20 Ibrohimov Axror Quva tumani 2-o'rin 3 12:17:33 20 / 20 Xoshimova Sarvinoz Qobiljon qizi Bag'dod tumani 3-o'rin 4 12:19:12 20 / 20 Mamataliyeva Dildoraxon Muhammadali qizi Yozyovon tumani 5 12:21:17 20 / 20 Umarova Sug'diyona Beshariq tumani 6 12:23:02 20 / 20 Egamnazarova Shahloxon Dang'ara tumani 7 12:23:24 20 / 20 Qodirov Javohir Beshariq tumani 8 12:24:38 20 / 20 Jo'raboyeva Zebiniso Farg'ona shahar 9 12:24:46 20 / 20 Sotvoldieva Guloyim Rustambekovna Farg'ona shahar 10 12:25:54 20 / 20 Ismoilova Gullola Farg'ona tumani 11 12:27:46 20 / 20 Bektosheva Mohlaroy Anvarjon qizi Farg'ona shahar 12 12:28:42 20 / 20 Turģunov Shukurullo Quva tumani 13 12:29:18 20 / 20 Yusupova Niginabonu Ne'mat qizi Quva tumani 14 12:29:20 20 / 20 Tohirjonova Diyora Farg'ona shahar 15 12:32:35 20 / 20 Abdullayeva Shaxnoza Farg'ona shahar 16 12:33:31 20 / 20 Qo'chqorov Jahongir O'zbekiston tumani 17 12:43:17 20 / 20 Arabboyev Jòrabek Quva tumani 18 12:48:56 20 / 20 Muhammadjonova Odina Yoqubjon qizi Qo'qon shahar 19 12:51:32 20 / 20 Abdumalikova Ruhshona Abrorjon qizi Dang'ara tumani 20 12:52:11 20 / 20 G'ulomjonov Muhammadjon Rishton tumani 21 12:52:25 20 / 20 Mirzayev Samandar Quva tumani 22 12:55:03 20 / 20 Toirov Samandar Quva tumani 23 12:56:05 20 / 20 Tolipova Gulmira Bag'dod tumani 24 12:57:36 20 / 20 Ikromjonova Shohroʻza Quva tumani 25 12:57:45 20 / 20 Solijonova Marxabo Bag'dod tumani 26 12:06:19 19 / 20 Ochildinova Nilufar -

Money Transfer Offices by PIXELCRAFT Name Address Working Hours

Money transfer offices by PIXELCRAFT www.pixelcraft.uz Name Address Working hours Operating Branch Office at the Operating Branch 7, Navoi Street, Shaykhontokhur District, from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM Tashkent City, Uzbekistan No lunch time Day offs: Saturday and Sunday Office at the banking service center 616, Mannon Uygur Street, Uchtepa from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM "Beshqayragoch" District, Tashkent City, Uzbekistan No lunch time Day offs: Saturday and Sunday Office at the banking service center 77, Bobur Street, Yakkasaray District, from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM "UzRTSB" Tashkent City, Uzbekistan No lunch time Day offs: Saturday and Sunday Office at the banking service center Tashkent region, Ikbol massif, Yoshlik from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM No lunch time “Taraqqiyot” Street, 1 (Landmark: Yunusabad district, Day offs: Saturday and Sunday on the side of the TKAD, opposite the 18th quarter, the territory of the building materials market) "Tashkent" Branch Office at Tashkent branch 11A, Bunyodkor Street, Block E, from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM Chilanzar District, Tashkent City, 100043, No lunch time Uzbekistan Day offs: Saturday and Sunday Office at the banking service center 60, Katartal Street, Chilanzar District, from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM "Katartal" Tashkent City, Uzbekistan No lunch time Day offs: Saturday and Sunday Office at the banking service center 24, "Kizil Shark" Street, Chilanzar District, from 9:00 AM till 6:00 PM "Algoritm" Tashkent City, Uzbekistan No lunch time Day offs: Saturday and Sunday Office at the banking service center 8, Beshariq -

Download 349.51 KB

i Due Diligence Report on Environment and Social Safeguards Final Report April 2015 UZB: Housing for Integrated Rural Development Investment Program Prepared by: Project Implementation Unit under the Ministry of Economy for the Republic of Uzbekistan and The Asian Development Bank ii ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DDR Due Diligence Review EIA Environmental Impact Assessment Housing for Integrated Rural Development HIRD Investment Program State committee for land resources, geodesy, SCLRGCSC cartography and state cadastre SCAC State committee of architecture and construction NPC Nature Protection Committee MAWR Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources QQB Qishloq Qurilish Bank QQI Qishloq Qurilish Invest This Due Diligence Report on Environmental and Social Safeguards is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 4 B. SUMMARY FINDINGS .................................................................................................. 4 C. SAFEGUARD STANDARDS -

Republican Road Fund Under Ministry of Finance of Republic of Uzbekistan REGIONAL ROAD DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (RRDP) Environmenta

Republican Road Fund under Ministry of Finance of Republic of Uzbekistan REGIONAL ROAD DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (RRDP) Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) Uzbekistan June 2016 1 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1.1 Introduction and the Background 5 1.2 Safeguards Policies 5 1.3 Impacts and their Mitigation and Management 6 1.4 Need for the Project – the “Do – Nothing – Option” 8 1.5 Public Consultation 8 1.6 Conclusion 8 2. INTRODUCTION 9 2.1 Project Description 9 2.2 Brief Description of the Project Roads 15 2.3 Description of project roads in Andijan region 20 2.4 Description of project roads in Namangan region 23 2.5 Description of project roads in Fergana region 25 2.6 Scope of Work 27 3. LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK 29 3.1 Requirements for Environmental Assessment in the Republic of Uzbekistan 29 3.2 Assessment Requirements of the World Bank 30 3.3 Recommended Categorization of the Project 31 3.4 World Bank Safeguards Requirements 31 3.4.1 Environmental Assessment (OP/BP 4.01) 31 3.4.2 Natural Habitats (OP/BP 4.04) 31 3.4.3 Physical Cultural Resources (OP/BP 4.11) 31 3.4.4 Forests (OP/BP 4.36) 31 3.4.5 Involuntary Resettlement (OP/BP 4.12) 32 3.4.6 International Waters (OP/BP 7.50) 32 3.4.7 Safety of Dams (OP/BP 4.37) 32 3.4.8 Pest Management (OP 4.09) 32 4. ASSESSMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS AND MITIGATION MEASURES 33 4.1 Methodology of the Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) 33 4.2 Screening of Impacts 33 4.2.1 Impacts and Mitigation Measures-Design Phase 35 4.2.2 Impacts and Mitigation Measures – Construction Phase 35 4.2.3 Impacts and Mitigation Measures - Operating Phase 48 5. -

T/R Vaqti Ball F.I.SH Hududingiz Maktab 1 12:06:41 9 / 10 Rahimova Mushtariy Sherzodbek Qizi Farg'ona Shahar 1-Maktab 1-O'rin 2

T/r Vaqti Ball F.I.SH Hududingiz Maktab 1 12:06:41 9 / 10 Rahimova Mushtariy Sherzodbek qizi Farg'ona shahar 1-maktab 1-o'rin 2 12:09:56 9 / 10 Jabborov Anvarjon Yozyovon tumani 15 maktab 2-o'rin 3 12:10:39 9 / 10 Журабоев Шохдил So'x tumani 18 3-o'rin 4 12:14:00 9 / 10 Abdullajonova Madina Farg'ona shahar 6 5 12:14:21 9 / 10 Abdullajonova Madina Farg'ona shahar 6 6 12:15:45 9 / 10 Зарафшонова Умида Yozyovon tumani 30 7 12:15:52 9 / 10 Asqarova Nozima Toshloq tumani 15-maktab 8 12:18:29 9 / 10 Madolimova Dilnura Toshloq tumani 30 9 12:18:45 9 / 10 Ro'ziqov islom Farg'ona shahar 6 10 12:20:06 9 / 10 Комилжонов шукурулло Yozyovon tumani 30 11 12:22:43 9 / 10 Маьмиржонова Нозима Yozyovon tumani 30 12 12:25:19 9 / 10 MadaminovMuxammadaxror25 Toshloq tumani 25 13 12:28:18 9 / 10 USMONOV Farg'ona tumani 15 14 12:01:34 8 / 10 MADAMINOVA MASHHURA Farg'ona shahar 4 15 12:01:36 8 / 10 7-maktab Farg'ona shahar 7 16 12:01:36 8 / 10 Xabibullayev Abdullo 2-IDUM Toshloq tumani 2-IDUM 17 12:01:37 8 / 10 Sodiqova Sevara Farg'ona shahar 41-maktab 18 12:01:53 8 / 10 Nurmuhammedova Diyorabonu Farg'ona tumani 52 19 12:01:58 8 / 10 Abdullayeva Marhonoy Farg'ona shahar 20-m 20 12:02:00 8 / 10 Bahodirova Sarvinoz Bag'dod tumani 11-maktab 21 12:02:05 8 / 10 Кобилжонов Одилжон Farg'ona tumani 19 мактаб 22 12:02:18 8 / 10 Muhammadmusayev Abubakr Rishton tumani 59 23 12:02:19 8 / 10 Турсуналиев Сардор Quvasoy shahar 22 24 12:02:20 8 / 10 Rafiqov abdulxamid 21maktab Beshariq tumani 21 maktab 25 12:02:23 8 / 10 Yaxyoyeva Muslimaxon Farg'ona shahar 5 26 12:02:23 8 / -

沙漠研究25-3, 237-240

沙漠研究 25-3, 237-240 (2015) Ἃ₍◊✲ Journal of Arid25-3, Land 237 -240Studies (2015) - ICAL 2 Refereed Paper - Journal of Arid Land Studies ̺ICAL 2 Refereed paper̺ Transfer and Localization of Sericulture Technology for Redeveloping Silk Industry in Central Asia - An Integrated Effort of Academic Research and Extension - Masaaki YAMADA*1), Yoshiko KAWABATA 2), Mitsuo OSAWA 1), Makoto IIKUBO 3), Umarov SHAVKAT 4), Vyacheslav APARIN 5) and Shiho KAGAMI 1) Abstract: Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology has been collaborating with the Uzbek Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources and the Uzbek Research Institute of Sericulture on two rural development projects in the Republic of Uzbekistan. This cooperative effort is sponsored by the Japan International Cooperation Agency. After concluding an initial project in the Fergana Valley, where environmental conditions are suitable for successful silkworm rearing, University staff and local Uzbek counterparts undertook follow-up research in some of the harshest climate conditions of Uzbekistan. This was done to ascertain the extent to which introduced sericulture technology might be adopted anywhere within Uzbekistan. In 2013, this follow-up project was launched in four communities of Shavat County in Uzbekistan’s Khorezm Province. The Japanese Kinshu × Showa autumn-breed and Shungetsu × Hosho spring-breed of silkworms (Bombyx mori) were distributed to cocoon producers, who received regular technical visits from the experts dispatched from Japan. All project participants were asked for their appraisal of the two introduced silkworm breeds, and associated rearing systems. They reported that they were satisfied with the increased cocoon harvests, and expressed their interest in acquisition of Japanese mulberry (Morus alba) cultivars, which they felt may better sustain the large appetites of the introduced silkworm breeds. -

From the History of Ancient Cities of the Fergana Valley (In the Example of Mingtepa-Ershi)

European Scholar Journal (ESJ) Available Online at: https://www.scholarzest.com Vol. 2 No. 5, MAY 2021, ISSN: 2660-5562 FROM THE HISTORY OF ANCIENT CITIES OF THE FERGANA VALLEY (IN THE EXAMPLE OF MINGTEPA-ERSHI) Hakimov Abdumuxtor Abduxalimovich Senior Lecturer, Department of History of Uzbekistan, Andijan State University, Doctor of Philosophy in History (PhD) Article history: Abstract: Received: 2th April 2021 This article analyzes the study of data on the cultural history of Mingtepa-Ershi, Accepted: 20th April 2021 an ancient major stage of urbanization in the Fergana Valley, by archaeologists. Published: 9th May 2021 The article also states that the ruins of Mingtepa-Ershi are located on the Great Silk Road and was one of the largest cities in the history of 2,500 years, which made a worthy contribution to the development of world civilization. Keywords: Mingtepa-Ershi, Central Asian civilization, Fergana valley, Pamir-Fergana expedition, Chust culture, Buddha, Afrosiab, Jarqo'ton, Akhsikat, Munchoktepa, Dalvarzintepa, Academy of Material Culture, urbanization In the historiography of the twentieth century, the main factors and stages of development of the process of emergence and formation of cities in the Fergana Valley have not been sufficiently studied. The main reasons for this process are that in many Soviet archeological works (mainly in the works of "central" scholars and some local researchers) the Fergana Valley is described as a periphery, bordering on Central Asian civilizations, and the history of Fergana cities is largely denied. In fact, another scientist from the “center,” Yu.A. Zadneprovsky (Leningrad) promoted the idea that urbanization in the valley began in the late Bronze-Early Iron Age (early I millennium BC) in the 70s of last century and always defended this idea. -

Out of the Cauldron, Into the Fire? 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

FOR HUMANFOR RIGHTS FORUM & UZBEK KRISTIAN LASSLETT PROFESSOR OF THE OUT CAULDRON, CENTRAL ASIA CENTRAL POWER BRIEFS | | BRIEFS POWER o2 FRisk and Ithe PrivatisationRE? of Uzbekistan’s Cotton Sector JUNE 2020 JUNE POWER BRIEFS | CENTRAL ASIA ABOUT THE SERIES SERIES EDITORS 2020 ABOUT THE REPORT AUTHOR Drawing on the systematic Professor Kristian Lasslett Kristian Lasslett is Professor of methodologies behind investigative Umida Niyazova Criminology and Head of School journalism, open source intelligence Dr Dawid Stanczak (Applied Social and Policy Sciences) gathering, big-data, criminology, and at Ulster University. He has pioneered political science, this series maps the investigative methods and data- transnational corporate, legal and modelling techniques for documenting governmental structures employed by the social networks, processes organisations and figures in Central and transactions essential to the Asia to accumulate wealth, influence organisation of grand corruption and and political power. The findings will kleptocracy. These techniques have be analysed from a good governance, also been employed to detect red flags human rights, and democratic in high risk governance environments. perspective, to draw out the big Professor Lasslett’s findings have picture lessons. featured in a wide range of leading international scientific journals, Each instalment will feature a digestible two monographs, feature length analytical snapshot centring on a documentaries and print-media exposés. particular thematic, individual, or organisation, delivered in a format that Uzbek Forum for Human Rights is designed to be accessible to the public, (formerly Uzbek-German Forum for useful to policy makers, and valuable to Human Rights / UGF) is a Berlin-based civil society. NGO dedicated to protecting human rights and strengthening civil society in Uzbekistan. -

Ada Metan Nukus" Мчж 2016-07-23

Нефть, газ (шу жумладан, сиқилган табиий ва суюлтирилган углеводород газини) ҳамда газ конденсатини қазиб чиқариш, қайта ишлаш ва сотиш учун лицензия тақдим этилган юридик шахслар тўғрисида МАЪЛУМОТ Лицензия серияси Лицензия берилган Т/Р Лицензия эгасининг тўлиқ номи ва рақами сана 1 АВ 1557 "ADA METAN NUKUS" МЧЖ 2016-07-23 2 АВ 1913 “QARAQALPAQ AVTO SERVIS” МЧЖ 2016-03-18 3 АА 0234 "Гулайым" МЧЖ 2018-11-14 4 АС 1211 "KOR-UNG INVESTMENT" МЧЖ 2020-12-07 5 АВ 2938 "Автогаз Эко Метан" МЧЖ 2016-07-23 6 АВ 3209 "Хожели Пропан Газ" МЧЖ 2017-06-04 7 АВ 3346 "BOLAT KAPITAL SERVIS" МЧЖ 2017-10-25 8 АА 0228 "Гулнора Газ Сервис" МЧЖ 2018-11-14 9 АА 0338 "Miymandos Nukus" МЧЖ 2019-01-30 10 АС 0082 "IDEAL GAZ" МЧЖ 2019-05-06 11 АС 1344 "АКК МЕTAN OIL" МЧЖ 2021-01-22 12 АС 0268 KARAKALPAK PROPAN NOKIS МЧЖ 2019-08-26 13 АС 0618 "Гулайым-2" МЧЖ 2020-02-07 14 АС 0634 "Нукус Метан Транс сервис" МЧЖ 2020-02-07 15 АС 0958 "MAX SERVICE GAZ" МЧЖ 2020-08-12 16 АС 1018 "JAYXUN MILANA" МЧЖ 2020-09-21 17 АС 1454 "MAMIR XAZINASI" МЧЖ 2021-03-19 18 АС 1066 "NAZLIMXAN ARZAYIM" МЧЖ 2020-10-23 19 АС 1204 "XUSHNUDBEK-XURSHIDBEK" МЧЖ 2020-12-07 20 АС 0322 "Дарбент Хужели" МЧЖ 2019-09-20 21 АВ 3036 "XOJELI METAN SERVIS" МЧЖ 2016-12-30 "KUNGRAD METAN TRADE" МЧЖ 22 АВ 3270 2017-07-14 "Каракалпак Авто Кемпинг" МЧЖ 23 АВ 3292 2017-07-14 "Канликул Иншоат тамирлаш" МЧЖ 24 АВ 3337 2017-09-12 "ANTAKIA GOLD" МЧЖ 25 АВ 0092 2018-08-03 "IRODA TAXIATASH" МЧЖ 26 АС 0276 2019-08-26 "Нукус Электрон Жихозлари" МЧЖ 27 АВ 1912 2018-03-13 "Шоманай Метан" МЧЖ 28 АА 0261 2019-11-29 Лицензия -

Download This Article in PDF Format

E3S Web of Conferences 258, 06068 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202125806068 UESF-2021 Possibilities of organizing agro-touristic routes in the Fergana Valley, Uzbekistan Shokhsanam Yakubjonova1,*, Ziyoda Amanboeva1, and Gulnaz Saparova2 1Tashkent State Pedagogical University, Bunyodkor Road, 27, Tashkent, 100183, Uzbekistan 2Tashkent State Agrarian University, University str., 2, Tashkent province, 100140, Uzbekistan Abstract. The Fergana Valley, which is rich in nature and is known for its temperate climate, is characterized by the fact that it combines many aspects of the country's agritourism. As a result of our research, we have identified the Fergana Valley as a separate agro-tourist area. The region is rich in high mountains, medium mountains, low mountains (hills), central desert plains, irrigated (anthropogenic) plains, and a wide range of agrotouristic potential and opportunities. The creation and development of new tourist destinations is great importance to increase the economic potential of the country. This article describes the possibilities of agrotourism of the Fergana valley. The purpose of the work is an identification of agro-tours and organization of agro-tourist routes on the basis of the analysis of agro-tourism potential and opportunities of Fergana agro-tourist region. 1 Introduction New prospects for tourism are opening up in our country, and large-scale projects are being implemented in various directions. In particular, in recent years, new types of tourism such as ecotourism, agrotourism, mountaineering, rafting, geotourism, educational tourism, medical tourism are gaining popularity [1-4]. Today, it is important to develop the types of tourism in the regions by studying their tourism potential [1, 3]. -

Research Park Following Tourism Capacity In

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ON ECONOMICS, FINANCE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Available online at www.researchparks.org IJEFSD RESEARCH PARK Journal homepage: www.researchparks.org/ FOLLOWING TOURISM CAPACITY IN FERGHANA VALLEY * Kambarov Zhamoliddin Hikmatullaevich, ** Komilzhanov Sherzodbek Ilkhomzhonovich * PhD in Economics, Associate Professor **3rd year student, direction of Management, Faculty of Management in Production, Ferghana Polytechnic Institute, Ferghana, Republic of Uzbekistan E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] A B S T R A C T A R T I C L E I N F O This article deals with the development of tourism in the Article history: Fergana valley and the way to innovation in the regions' Received 15 November 2019 economic activity using the broad opportunities available Received in revised form 1 December 2019 to domestic and foreign tourism in the Republic of Accepted 06 December 2019 Uzbekistan. Keywords: Tourism industry, al- Fargana grove, Click here and insert your abstract text. temurids dynasty, Brief description, Video © 2019 Hosting by Research Parks. All rights reserved. marketing. When foreign tourists are told about traveling to Uzbekistan, 1. Introduction tour agencies often talk about the historical monuments of Bukhara, Samarkand and Khiva, but we also have a lot of During the videoconference of the President of the Republic sights in the Fergana valley. Below are the following: of Uzbekistan on the implementation of investment projects 1. Historical monuments and tourist centers of Margilan city on January 8, 2019, he also touched upon the tasks of the of Ferghana region are as follows: social complex of the Cabinet of Ministers and emphasized the importance of attracting direct investments in the tourism industry.