The Baba-E-Urdu: Abdul Haq and the Role Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hindi and Urdu*

saadat hasan manto Hindi and Urdu* The hindi-urdu dispute has been raging for some time now. Maulvi Abdul Haq Sahib, Dr. Tara Singh, and Mahatma Gandhi know what there is to know about this dispute. For me, though, it has so far remained incomprehensible. Try as hard as I might, I just havenít been able to understand. Why are Hindus wasting their time supporting Hindi, and why are Muslims so beside themselves over the preservation of Urdu? A language is not made, it makes itself. And no amount of human effort can ever kill a language. When I tried to write something about this current hot issue, I ended up with the following conversation: munshi narain parshad: Iqbal Sahib, are you going to drink this soda water? mirza muhammad iqbal: Yes, I am. munshi: Why donít you drink lemon? iqbal: No particular reason. I just like soda water. At our house, everyone likes to drink it. munshi: In other words, you hate lemon. iqbal: Oh, not at all. Why would I hate it, Munshi Narain Parshad? Since everyone at home drinks soda water, Iíve sort of grown accustomed to it. Thatís all. But if you ask me, actually lemon tastes better than plain soda. munshi: Thatís precisely why I was surprised that you would prefer something salty over something sweet. And lemon isnít just sweet, it has a nice flavor. What do you think? * ìHindī aur Urdū,î ManÅo-Numā (Lahore: Sañg-e Mīl Publications, 1991), 560– 63. 205 206 • The Annual of Urdu Studies, No. 25 iqbal: Youíre absolutely right. -

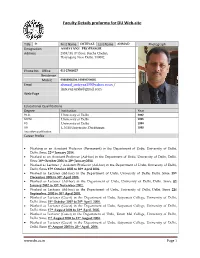

Faculty Details Proforma for DU Web-Site

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site Title Dr. First Name IMTEYAZ Last Name AHMAD Photograph Designation ASSISTANT PROFESSOR Address 2839/40, 4th floor, Kucha Chelan, Daryaganj, New Delhi. 110002. Phone No Office 011-27666627 Residence Mobile 09868008294 / 09899754685 Email [email protected] / [email protected] Web-Page Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. University of Delhi 2002 M.Phil. University of Delhi 1996 PG University of Delhi 1994 UG L.N.M.University, Darbhanga 1990 Any other qualification Career Profile Working as an Assistant Professor (Permanent) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 22nd January 2014. Worked as an Assistant Professor (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 16th October 2006 to 20th January2014. Worked as Lecturer / Assistant Professor (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 17th October 2005 to 30th April 2006. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 28th December 2004 to 30th April 2005. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 8th January 2002 to 15th November 2002. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 21st September. 2000 to 30th April 2001. Worked as Lecturer (Guest) in the Department of Urdu, Satyawati College, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 31st October 2007 to 20th April. 2008. Worked as Lecturer (Guest) in the Department of Urdu, Satyawati College, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 17th August 2004 to 23rd April. -

Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology

Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology Merit List Department of Arabic (Bachelors, Morning) 2020 Abdul Haq Campus S# Form No Name Father Percent 1 202764 RABIAA MUHAMMAD AMIN 91.18 2 202095 NOORULAIN MUHAMMAD RAFIQ 67.27 3 205559 NASIR HUSSAIN KHUDA YAR 61.69 4 206180 ATA UR REHMAN ZAKIR UR REHMAN 54.22 Note: This list is conditional (Subjected to approval of Prof. Dr. Muhammad Zahid Concern Department and Varification of Documents). (Director Admission) Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology Merit List Department of Education (B.Ed 2.5 Years) (Bachelors, Morning) 2020 Abdul Haq Campus S# Form No Name Father Percent 1 204745 BUSHRA SAMI MUHAMMAD SAMI 78.34 2 204747 RUBAB SAMI MUHAMMAD SAMI 78.21 3 206250 SYED HASSNAN SYED MUHAMMAD SHAH 69.70 4 207469 MUHAMMAD AFTAB SARWAR MUHAMMAD SARWAR MALIK 68.67 5 205695 ALTAF AHMED MUHAMMAD MUNSIF 66.68 6 206100 MUHAMMAD FAIZAN MUHAMMAD IMRAN 66.38 7 200210 RAFIA FAROOQ MUHAMMAD FAROOQ 65.13 8 203771 NIMRAH AFTAB AFTAB AHMED 62.42 9 206939 MARINA RIAZ AHMED 61.70 10 203927 NUSRAT JABEEN DEEN MUHAMMAD 61.50 11 207432 BISMA MUHAMMAD YOUSUF BALOCH 60.69 12 202584 SEHRISH MUHAMMAD RIAZ 60.10 13 206963 HAYAT KHATOON KORAI MAZHAR UL HAQUE 60.00 14 202094 HUMAIRA MUHAMMAD KHAN 57.20 15 206719 ABDUL SAMAD MUHAMMAD RIAZ 56.36 16 206127 NAZIA MUHAMMAD YOUNUS 56.25 Note: This list is conditional (Subjected to approval of Prof. Dr. Muhammad Zahid Concern Department and Varification of Documents). (Director Admission) Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology Merit List -

The Khilafat Movement in India 1919-1924

THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR T AAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 62 THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 A. C. NIEMEIJER THE HAGUE - MAR TINUS NIJHOFF 1972 I.S.B.N.90.247.1334.X PREFACE The first incentive to write this book originated from a post-graduate course in Asian history which the University of Amsterdam organized in 1966. I am happy to acknowledge that the university where I received my training in the period from 1933 to 1940 also provided the stimulus for its final completion. I am greatly indebted to the personal interest taken in my studies by professor Dr. W. F. Wertheim and Dr. J. M. Pluvier. Without their encouragement, their critical observations and their advice the result would certainly have been of less value than it may be now. The same applies to Mrs. Dr. S. C. L. Vreede-de Stuers, who was prevented only by ill-health from playing a more active role in the last phase of preparation of this thesis. I am also grateful to professor Dr. G. F. Pijper who was kind enough to read the second chapter of my book and gave me valuable advice. Beside this personal and scholarly help I am indebted for assistance of a more technical character to the staff of the India Office Library and the India Office Records, and also to the staff of the Public Record Office, who were invariably kind and helpful in guiding a foreigner through the intricacies of their libraries and archives. -

Aijaz Ahmad.Pdf

( C ((((((((((( ( c ^ O 4,';. m . : - \ . Political Essays ('S' A i j a zAhmad ■‘■S. % i( ((((((((( C (( ( Azad's Careers; Roads Taken and Not Taken Maulana Abul Kalam A/ad was undoubtedly one of the seminal figures in the Indian National Movement, and he came to ’ occupy, after Ansari’s death in 1936, an unassailable position among the nationalist Muslims as they were represented in the Indian National Congress.1 His Presidential Address at the Ramgarh Session of the Congress in March 1 940, merely a few days before Jinnah was to unveil the historic Pakistan Resolution at the Lahore Session of the t Muslim League, is one of the noblest statements of Indian secular nationalism and a definitive refutation of the so-called ‘two-nation theory’,2 Likewise, his attempt at reinterpreting Islamic theology itself in such a way as to make it compatible witli the religiously composite, politically secular trajectory of India, which found its 1 I use the awkward phrase ‘nationalist Muslims as they were represented in the Indian National Congress’ in more or less the same sense in which Mushirul Hasan uses the simple term ‘Congress M uslims’ in, for example, his recent Nationalism and Communal Politics in India 1885-1930 (Delhi: Manohar, 1991). The longer phrase is used here for a certain emphasis. There were also great many nationalist Muslims who did not join the Congress. Many more worked primarily m or around the Communist Party than is generally recognized; some others went into smaller parties of various types; an incalculable number did not join any party because of more or less equal discomfort with League policies and the presence of substantial Hindu communalist forces inside the Congress. -

Hajji Din Mohammad Biography

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Hajji Din Mohammad Biography Hajji Din Mohammad, a former mujahedin fighter from the Khalis faction of Hezb-e Islami, became governor of the eastern province of Nangarhar after the assassination of his brother, Hajji Abdul Qadir, in July 2002. He is also the brother of slain commander Abdul Haq. He is currently serving as the provincial governor of Kabul Province. Hajji Din Mohammad’s great-grandfather, Wazir Arsala Khan, served as Foreign Minister of Afghanistan in 1869. One of Arsala Khan's descendents, Taj Mohammad Khan, was a general at the Battle of Maiwand where a British regiment was decimated by Afghan combatants. Another descendent, Abdul Jabbar Khan, was Afghanistan’s first ambassador to Russia. Hajji Din Mohammad’s father, Amanullah Khan Jabbarkhel, served as a district administer in various parts of the country. Two of his uncles, Mohammad Rafiq Khan Jabbarkhel and Hajji Zaman Khan Jabbarkhel, were members of the 7th session of the Afghan Parliament. Hajji Din Mohammad’s brothers Abdul Haq and Hajji Abdul Qadir were Mujahedin commanders who fought against the forces of the USSR during the Soviet Occupation of Afghanistan from 1980 through 1989. In 2001, Abdul Haq was captured and executed by the Taliban. Hajji Abdul Qadir served as a Governor of Nangarhar Province after the Soviet Occupation and was credited with maintaining peace in the province during the years of civil conflict that followed the Soviet withdrawal. Hajji Abdul Qadir served as a Vice President in the newly formed post-Taliban government of Hamid Karzai, but was assassinated by unknown assailants in 2002. -

Scanned Using Scannx OS16000 PC

/' \ / / SAGAR 2017-2018 CHIEF EDITORS Sundas Amer, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Charlotte Giles, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Paromita Pain, Dept, of Journalism, UT Austin ^ EDITORIAL COLLECTIVE MEMBERS Nabeeha Chaudhary, Radio-Film-Television, UT Austin Andrea Guiterrez, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Hamza Muhammad Iqbal, Comparative Literature, UT Austin Namrata Kanchan, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Kathleen Longwaters, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Daniel Ng, Anthropology, UT Austin Kathryn North, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Joshua Orme, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin David St. John, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Ramna Walia, Radio-Film-Television, UT Austin WEB EDITOR Charlotte Giles & Paromita Pain PRINTDESIGNER Dana Johnson EDITORIAL ADVISORS Donald R. Davis, Jr., Director, UT South Asia Institute; Professor, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT-Austin Rachel S. Meyer, Assistant Director, UT South Asia Institute EDITORIAL BOARD Richard Barnett, Associate Professor, Dept, of History, University of Virginia Eric Lewis Beverley, Assistant Professor, Dept, of History, SUNY Stonybrook Purmma Bose, Associate Professor, Dept, of English, Indiana University-Bloomineton Laura Brueck, Assomate Professor, Asian Languages & Cultures Dept., Northwestern University Indrani Chatterjee, Dept, of History, UT-Austin uiuversiiy Lalitha Gopalan, Associate Professor, Dept, of Radio-TV-Film, UT-Austin Sumit Guha, Dept, of History, UT-Austin Kathryn Hansen, Professor Emerita, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT-Austin Barbara Harlow, Professor, Dept, of English, UT-Austin Heather Hindman, Assistant Professor, Dept, of Anthropology, UT-Austin Syed Akbar Hyder, Associate Professor, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT-Austin Shanti Kumar, Associate Professor, Dept, of Radio-Television-Film, UT-Austin Janice Leoshko, Associate Professor, Dept, of Art and Art History, UT-Austin W. -

Effective from the Academic Year 2011-2012 Onwards

B.A. (HONOURS) URDU (Three Year Full Time Programme) COURSE CONTENTS (Effective from the Academic Year 2011‐2012 onwards) DEPARTMENT OF URDU UNIVERSITY OF DELHI DELHI - 110007 1 University of Delhi Name of the Department: Urdu Course: B.A. (Hons.) Urdu Paper-I : Study of Prose and Poetic form of Urdu Literature (Art and Short History) Paper-II :Option-1 :Introduction of Persian Semester I Option-2 : Study of Modern Prose Option-3: Study of Progressive Poetry Paper- III : Study of Art, History of Prose Form Paper IV - Concurrent – Qualifying Language Paper-V: Option-1: Persian Prose and Poetry Option 2: Study of Medieval Prose Semester II Option 3: Study of Modern Nazm, Ghazal Paper-VI: Special Study of Literary Movements Paper VII - Concurrent – Credit Language Paper-VIII :Option 1: Special Study of Prem Chand as a Short Story Writer Option 2: Special Study of Rajinder Singh Bedi as a Short Semester III Story Writer Option 3: Special Study of Woman Short Story Writer Paper-IX: Study of Modern Literary Movements Paper X - Concurrent – Interdisciplinary Paper-XI: Option 1: Special Study of a Poet (Ghazal Go) Meerataqui Meer Semester IV Option 2: Special Study of a Poet (Ghazal Go) Ghalib 2 Paper-XII: Study of Classical Prose & Poetry Paper XIII - Concurrent – Discipline Centered I Paper-XIV: Study of Medieval Poetry Paper-XV :Option 1 :Study of Prose Form Afsana Semester V Option 2: Study of Prose Form Drama Paper-XVI: Study of Development of Urdu Language & Literature Paper-XVII: Study of Print Media and Journalism Paper-XVIII: Study of Mass Media (Electronic) Paper-XIX : Special Study of Art of News Reporting Semester VI Paper-XX :Option 1: Detail Study of a Poet Iqbal Option 2: Detail Study of Shibli Paper XXI - Concurrent – Discipline Centered II 3 SEMESTER BASED UNDER‐GRADUATE HONOURS COURSES Distribution of Marks & Teaching Hours The Semester‐wise distribution of papers for the B.A. -

Report on Citizenship Law:Pakistan

CITIZENSHIP COUNTRY REPORT 2016/13 REPORT ON DECEMBER CITIZENSHIP 2016 LAW:PAKISTAN AUTHORED BY FARYAL NAZIR © Faryal Nazir, 2016 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. EUDO Citizenship Observatory Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies in collaboration with Edinburgh University Law School Report on Citizenship Law: Pakistan RSCAS/EUDO-CIT-CR 2016/13 December 2016 © Faryal Nazir, 2016 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), created in 1992 and directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. The Centre is home to a large post-doctoral programme and hosts major research programmes, projects and data sets, in addition to a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration, the expanding membership of the European Union, developments in Europe’s neighbourhood and the wider world. -

Usage of Urdu As the Language of Elitism Among the Muslims of the Northern and the Deccan Parts of India: a Socio-Cultural Review

Middle Eastern Journal of Research in Education and Social Sciences (MEJRESS) Website: http://bcsdjournals.com/index.php/mejrhss ISSN 2709-0140 (Print) and ISSN 2709-152X (Online) Vol.1, Issue 2, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.47631/mejress.v1i2.28 Usage of Urdu as the Language of Elitism among the Muslims of the Northern and the Deccan parts of India: A Socio-Cultural Review Arshi Siddiqui, 1 Ismail Siddiqui 2 1 PhD, Barkatullah University, Bhopal (M.P), India. 2 Integrated Masters, Development Studies, IIT Madras, Chennai, (T.N), India Abstract Article Info Purpose: The paper examines how Urdu evolved from the language of the Article history: rulers to the lingua franca of Muslims in the modern times. The paper Received: 02 September 2020 attempts to highlight how Urdu is still being used as an identity marker for Revised: 08 October 2020 Muslims with respect to the other communities and is a source of Accepted: 18 October 2020 ascendancy, an achieved elitist status within the Muslims of the North and Deccan. Keywords: Approach/Methodology/Design: Socio-cultural analysis. Findings: The usage of Urdu as a political instrument by the Muslim Sociolinguistics, League and the cultural influence the language has exerted on the Muslim Urdu, community led to its usage as a source of elitism within the community in the South Asia, modern times. The analysis indicates that there is harking back to the highly Indian Muslims, Persianised, nastaliq form of Urdu, which was manifested in its literature in Elitism the twentieth century as the pure, hegemonic and the aspired language, true to the identity of the community. -

OPF Head Office

List of UNCC Un Registered Claimants for Interest Markup Payment Returned- Head Office S. No National No Name Father's Name Old NIC 1 103807 AMEER SULTAN HAMEED ULLAH 506-50-293053 2 103901 SABIR HUSSAIN KHAN BAHADAR KHAN 224-58-572755 3 105765 ALLAH DITTA DIN MUHAMMAD 224-90-012714 4 109980 SHAMIM SHAHSAWAR RAJA SHAHSAWAR 221-92-580128 5 114764 GHULAM NABI ALLAH DITTA 220-24-163473 6 150249 OURANGZEB MUHAMMAD SHARIF 301-58-297399 7 150281 JAMSHAD IQBAL CHAUDHRY MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN 224-59-104875 8 13558 HAJI MUHAMMAD DIN QADIR BUKHSH 211-27-125982 9 13577 RIAZ AHMAD 10 71 MUHAMMAD IQBAL FATEH ALI 269-47-196836 11 98 JAVED IQBAL FAZAL ELLAHI 214-39-234841 12 103 MUHAMMAD ASLAM ABBAS ALI 210-57-378648 13 282 FAYYAZ UL HAQUE MALIK FAIZ UL HAQ 217-25-218919 14 513 MUMTAZ ALI MALIK MALIK GHULAM MUHAMMAD 210-85-041678 15 538 MALIK MAHMOOD HUSSAIN AKBAR HUSSAIN 220-92-256507 16 587 MUHAMMAD IFTIKHAR MUHAMMAD AMAN 211-59-080432 17 592 MUHAMMAD IFTIKHAR ANWAR GHULAM ALI 300-53-132694 18 735 MUHAMMAD ASHRAF MUHAMMAD DIN 301-49-261432 19 749 SYED MEHTAB AHMAD SYED ABDUS SAMI 101-91-466638 20 806 QAMAR ZAMAN SHER ZAMAN 710-90-349515 21 1115 MUNIR HUSSAIN SHAH SYED MEHDI SHAH 101-27-562475 22 1196 MUHAMMAD RIAZ MUHAMMAD DIN 211-57-203718 23 1197 FEROZ DIN YASEEN 510-52-193405 24 1206 MUHAMMAD MALIK RAJAY KHAN 221-44-303356 25 1408 GUL JAHAN SHAH MIR SAHIB SHAH 155-53-397539 26 1418 MUHAMMAD AZAM KHOKHAR HAYAT MUHAMMAD KHOKHAR 101-51-624257 27 1495 WALAYAT KHAN BAHADAR KHAN 225-38-491633 28 1521 MUHAMMAD NAWAZ REHMAT KHAN 228-53-643072 29 1571 KHALIL BUTT ABDUL GHANI 276-44-291443 30 1596 MARGRATE D'COSTA CHARLIS FRANCIS 211-48-460787 31 1598 MUHAMMAD MANDAR MUHAMMAD DIN 225-55-347212 32 1599 JALIL UR REHMAN SUFI GUL NAWAZ 220-62-463192 33 1613 MUHAMMAD AKHTAR AMAM DIN 216-44-212685 34 1682 MUHAMMAD YASIN HASSAN HASSAN MUHAMMAD 266-46-100966 35 1683 TAHIR SADDIQUE RAJA M. -

Indo-Persian Manuscripts Issues and Challenges in the Modern Time (6-8 March 2020) the English and Foreign Languages University Hyderabad, India

3 Day International Conference on Indo-Persian Manuscripts Issues and Challenges in the Modern Time (6-8 March 2020) The English and Foreign Languages University Hyderabad, India Department of Asian Languages in collaboration with British Institute of Persian Studies, London, UK organises 3 Day International Conference on Indo-Persian Manuscripts Issues and Challenges in the Modern Time (6-8 March 2020) Inauguration by Prof. E. Suresh Kumar Hon’ble Vice Chancellor, EFL University Friday 6th March 2020, 5:00 pm Room no. 1, Ground Floor, New Academic Block EFL University, Hyderabad Concept Note: India and Persia have had close contact in the realm of language, literature and culture through the ages. Since the 12th century many parts of the subcontinent became the hub of Persian learning and played a vital role in promoting and propagating Indo-Persian literary heritage. The Mughals, the Nizams of Hyderabad, the Nawabs of Bengal, the Officials of the British Raj, the great Orientalists and the Indian scholars have collected Persian manuscripts, documents, miniatures and artifacts which are now in the treasure trove of libraries and museums of India and abroad. Persian language started enjoying the status of administrative language of India since 13th century and continued till 1837 when it was finally abolished as the official language. During this vast period of six centuries, thousands of books were written in Persian, and tens and hundreds of poets composed their poems in this language. Copies of their rare works have been preserved in different libraries in the subcontinent in the form of manuscripts. The libraries and museums of India are full of with these rare documents.