TWIP Steels for Automotive Applications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aspects of Heat Flow in Laser Processing of Metals Luleå University of Technology 2018

DOCTORAL T H E SIS Department of Engineering Sciences and Mathematics Sundqvist Jesper Division of Product and Production Development Aspects of Heat Flow in ISSN 1402-1544 Laser Processing of Metals ISBN 978-91-7790-051-1 (print) ISBN 978-91-7790-052-8 (pdf) Aspects of Heat Flow in Laser Processing of Metals in Laser Processing Aspects of Heat Flow Luleå University of Technology 2018 Jesper Sundqvist Manufacturing Systems Engineering Doctoral Thesis Aspects of heat flow in laser materials processing Jesper Sundqvist Luleå University of Technology Department of Engineering Sciences and Mathematics Division of Product and Production Development 971 87 Luleå Sweden Luleå, March 2018 Printed by Luleå University of Technology, Graphic Production 2018 ISSN 1402-1544 ISBN 978-91-7790-051-1 (print) ISBN 978-91-7790-052-8 (pdf) Luleå 2018 www.ltu.se I. Preface The writing of this Ph. D thesis and the research behind it has been conducted at the research subject ('chair') of Manufacturing Systems Engineering at Luleå University of Technology. I want to express my gratitude to my supervisors Prof. Dr. Alexander Kaplan and Adj. Prof. Dr. John Powell for their support and guidance. Without them this work would not have been possible. I would like to thank all the colleagues at the research team for help given during my research and also all colleagues at the division for all the interesting conversations during coffee breaks. Particular thanks to Stephanie Robertson for proof reading of parts of the thesis. I also want to thank Christina Lundebring and Marie-Louise Palmblad for all the help with administrative tasks. -

Tension and Compression Asymmetry and the Bauschinger Effect

TENSILE TESTING Tension and Compression Asymmetry and the Bauschinger Effect APRIL 2021 1 Plastometrex Tension/Compression Asymmetry and the Bauschinger Effect TENSION/COMPRESSION ASYMMETRY AND THE BAUSCHINGER EFFECT Testing in (uniaxial) compression is sometimes an attractive alternative to tensile testing. Specimens can be simpler in shape and smaller, since there is no gripping requirement. The key question is whether corresponding information can be obtained. In general, it can, but there is sometimes a perception that at least some materials behave differently under compression - ie that there is tensile-compressive asymmetry in their response. In fact, this is largely a myth. At least in the majority of cases, the underlying plasticity response is symmetrical. The von Mises (deviatoric) stress, which is normally taken to be the determinant of the response, is identical in the two cases. However, caveats are needed. If the material response is indeed dependent on the hydrostatic component of the stress, as it might be for porous materials and for those in which a phase transformation occurs during loading, then asymmetry is possible. Also, while the underlying plasticity response is usually the same, the compressive stress- strain curve is often affected by friction between sample and platen (leading to barreling). Conversely, the necking that may affect the tensile curve cannot occur in compression. It’s also important to distinguish the concept of tension / compression asymmetry from that of the Bauschinger effect (a sample pre- loaded in tension exhibiting a different response if then loaded in compression). Plastometrex 1 1 Tension/Compression Asymmetry and the Bauschinger Effect TENSION/COMPRESSION where these strains refer to plastic values. -

Analysis of Hadfield Scrap Shredder Hammer Fracture and Replacing It

Engineering Failure Analysis 109 (2020) 104230 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Engineering Failure Analysis journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/engfailanal Analysis of hadfield scrap shredder hammer fracture and replacing it with carbide-free nano-bainitic steel T ⁎ ⁎ Behdad Garmeha, Masoud Kasiri-Asgarania, , Kamran Aminib,c, , Hamid Ghayoura a Advanced Materials Research Center, Department of Materials Engineering, Najafabad Branch, Islamic Azad University, Najafabad, Iran b Department of Mechanical Engineering, Tiran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran c Center for Advanced Engineering Research, Majlesi Branch, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Shredders are widely used in metal scrap recycling. The Shredder device includes hammers Shredder joined to a massive rotor. Hammers are responsible for grinding, therefore, play a key role in the Hammer shredder. Most of the casted hammers are made from austenitic manganese steel. Austenitic Austenitic manganese steels manganese steels usually have good mechanical properties at impact and wear use but in field Work hardening use as shredder hammer, they are faced to the different type of failures. Finding reasons for these Mechanical properties failures could help increasing shredding efficiency and reducing cost. In this study, several fac- Nano bainitic steel tors, such as the lack of work hardening of the as quench hammer, low yield strength and tensile strength, carbide growth at the user's temperature and stopping the work hardening at tem- peratures between 200 and 300 °C have been defined as reasons of failure. Regarding these points, castable Nano bainitic steel suggested as an alternative to the austenitic manganese steels. In file test results proved that nano bainitic steel hammers has better performance than austenitic manganese steel hammers. -

Austenitic Manganese Steel, Called "SLL" by M.C.S.D

WELDING OF AUSTENITIC MANGANESE STEEL Austenitic Manganese steel, called "SLL" by M.C.S.D. or Hadfield Manganese ! Steel by the materials community is an extremely tough non-magnetic alloy in which the usual hardening transformation that occurs in low alloy steel has been suppressed by the high manganese content. It is characterized by high strength, high ductility and good wear resistance. The welding of "SLL" requires considerable care. Though it is very tough, it is sensitive to reheating, so caution is necessary to avoid embrittle- ment. Arc welding is entirely practical and many tons of austenitic man- ganese steel electrodes are used annually. Experience and research have shown that the following procedures are helpful: 1. Welds in which both parts are "SLL" should be made with covered man- ganese steel electrodes that meet the requirements of AWS Spec. A5.13 Classification EFeMn-A. 2. Welds in which one part is "SLLw and the other part is carbon or low alloy steel should be made with covered stainless steel electrodes that meet the requirements of AWS Spec. A5.4 - Classification E309. 3. Never weld "SLL" with carbon or low alloy steel electrodes. 4. In manual welding, the electrode is always inclined in the direction of the weld bead travel. pushing the arc might give gassy, unsound deposits. 5. Oxy-acetylene welding of "SLL" should be avoided since it is likely to cause marked embrittlement of the base metal. 6. The energy input per inch should be kept to minimum values consistent with sound welds. 7. The maximum suggested heat input for "SLL" is 65,000 joules. -

Department Mechanical Engineering ME8491- Engineering Metallurgy Unit II - MCQ Bank 1

ChettinadTech Dept of MECH Department Mechanical Engineering ME8491- Engineering Metallurgy Unit II - MCQ Bank 1. Alloy of copper and zinc is known as __________ A. Brass B. Bronze C. Duralumin D. Nichrome ANSWER: (A) 2. Major constituent of the gun metal is ____________ A. Copper B. Nickel C. Iron D. Zinc ANSWER: (A) 3. Major constituent of Duralumin alloy is ____________ A. Copper B. Nickel C. Iron D. Aluminum ANSWER: (D) 4. Cast iron is a product of ___________ A. Cupola B. Bessemer converter C. Open hearth furnace D. Blast furnace ANSWER: (A) 5. Wrought iron is a product of ___________ A. Cupola B. Bessemer converter C. Puddling furnace D. Blast furnace ANSWER: (C) ME8491 – Engineering Metallurgy Page 1 ChettinadTech Dept of MECH 6. Red hardness of an alloy steel can be improved by adding ____________ A. Tungsten B. Vanadium C. Manganese D. Titanium ANSWER: (A) 7. Abrasion resistance of an alloy steel can be improved by adding ___________ A. Tungsten B. Vanadium C. Manganese D. Chromium ANSWER: (D) 8. Wear resistance of an alloy steel can be improved by adding ___________ A. Tungsten B. Vanadium C. Manganese D. Titanium ANSWER: (C) 9. Corrosion resistance of an alloy steel can be improved by adding ___________ A. Tungsten B. Vanadium C. Chromium D. Titanium ANSWER: (C) 10. Tensile strength of an alloy steel can be improved by adding ____________ A. Nickel B. Vanadium C. Manganese D. Titanium ANSWER: (A) 11. Which of the following induces fine grain distribution in alloy steel? A. Nickel B. Vanadium C. Manganese D. Titanium ANSWER: (B) 12. -

SANDRA SWIFT and the Land Speed Record

Dedication It's not normally my practice to dedicate my works but, in this case, I wanted to make a special exception. This novel goes out, with the utmost respect and admiration, to a unique group of people whose number includes: Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat Louis Rigolly Henry Segrave Sir Malcolm Campbell Craig Breedlove Donald Malcolm Campbell Tom Green Art Arfons Bob Summers Gary Gabelich Richard Noble Andy Green Edward Shadle, Keith Zanghi and the rest of the American Eagle Team And, finally, to George Harrison! ("He's the Master of Going Faster") Chapter One: A Blast From The Past. "How fast is it going?" Brushing a bit of her hair aside, Phyllis Newton raised a hand to her forehead and peered up at the smooth contrail arcing across the blue New York sky. "Well, even with our developments in sound reduction, we usually try to comply with local regulations in regards to flights," she explained. "Even those of a test nature, so a lot of our local flights tend to be below supersonic. Most of our sustained high speed flights take place out west, at the Dryden Research Center in California. We also," she added, her smile growing, "occasionally conduct high speed test runs once our planes are out over the ocean and heading for our facility at Fearing Island." She looked back down at her audience. The thirty boys and girls from the Corning- Painted Post School District were, for the most part, following the progress of the distant aircraft. Some of them, however, were still staring around at the buildings, towers and general activity of the enormous complex which made up the grounds of Swift Enterprises. -

Abrasion Resistance Where It Counts. ® 400 • 450 • 500 PLATE

ABRASION RESISTANCE WHERE IT COUNTS. ® 400 • 450 • 500 PLATE TYPICAL CHEMICAL ANALYSIS AND PHYSICAL PROPERTIES Wearalloy 400 Wearalloy 450 Wearalloy 500• Carbon .12/.16 .18/.26 .27/.30 Mang. (max.) 1.55 1.20 .95 Phos. (max.) .025 .025 .025 Sulphur (max.) .005 .005 .005 Silicon .35/.55 .40/.55 .45/.55 Boron .0005/.005 .0005/.005 .0005/.005 Chrome (max.) .55 .65 .75 Nickel (max.) .35 .35 .35 Moly (max.) .55 .60 .65 Hardness (BHN) 388-430 444-475 477-544 Yield (psi.) 156,000 170,000 182,000 Tensile (psi.) 194,000 206,000 235,000 Elongation in 2” 19% - 23% 18% - 23% 17% - 23% Color Code Yellow/Red Yellow/Blue Yellow/Purple Thickness: 1/8” through 4” Widths: 48” through 96” Lengths: 96” through 288” • 550 BHN plate available for more severe abrasion in 1/4”, 3/8”, 1/2” and 3/4” thickness. APPLICATIONS Aggregate, Construction, and Mining Drag Slat Conveyor Liners Crusher Liners Cone Crusher Main Frame Liners Hopper Liners Transfer Points Screed Plates Mold Board Liners Underground Miners Scraper Liners Feeders Skid Plates Truck Bed Liners Drag Line Bucket Liners Chute Liners Asphalt Plant Ductwork Jaw Crusher Cheek Plates Loader Bucket Liners Shovel Bucket Liners Rock Box Liners Hammers Screen Decks Cutting Edges For Pulp and Paper Industry Applications - See Page 5 2 GEnErAL TEchnicAL information Wearalloy 400, 450, and 500 are heat treated, quenched, and tempered alloy steels that are used in applications where shock and abrasion are the primary cause of failure. Wearalloy 400 (388 - 430 BHN) and Wearalloy 450 (440 - 470 BHN) provide excellent resistance to impact and sliding abrasion. -

Defects Evaluation on Hadfield Steel Sheets

® 2016 a *+ *6 */01- . - / w"#$ - 9 DEFECTS EVALUATION ON HADFIELD STEEL SHEETS ŽÁNSKÝ Ond ej, K ÍŽ Antonín Z U - University of West Bohemia, Pilsen, Czech Republic, EU [email protected] , [email protected] Abstract The key characteristic of austenitic Hadfield´s steel is its toughening (hardening) under mechanical loading (during operation). By the influence of mechanical loading austenite transformed to martensite, resulting in surface hardening (curing) with a good toughness. High abrasion resistance is the result. Due to very difficult machinability and weldability are the final products made generally of either as casting or as simple parts made of rolled sheets. This paper describes the most common faults on rolled sheets and their influence on abrasion resistance. As base for samples selection sheets of normal production were chosen on which were identified following defects: decarburized layer on surface, carbides on the grain boundaries, and martensitic structure in delivered condition before any mechanical loading. For the comparison of abrasive resistance was used test in shot blasting machine. Weight difference was evaluated on each sample. Achieved results confirmed that the samples which were grinded of (surface defects removing) have about 25 to 40 % less weight loss than the samples which were left in common delivery conditions. Keywords: Hadfield steel, X120Mn12, carbides, decarburized layer, wear resistance 1. INTRODUCTION Mangalloy, also called manganese steel or Hadfield steel, after its discoverer Sir Robert Abott Hadfield, is a steel alloy containing an average of around 13% manganese. This steel is known for its high impact strength and resistance to abrasion once in its work-hardened state. -

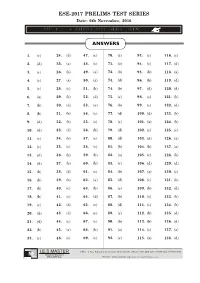

Ese-2017 Prelims Test Series Answers

ESE-2017 PRELIMS TEST SERIES Date: 6th November, 2016 ANSWERS 1. (c) 24. (d) 47. (c) 70. (c) 93. (c) 116. (c) 2. (d) 25. (a) 48. (c) 71. (a) 94. (c) 117. (d) 3. (c) 26. (b) 49. (a) 72. (b) 95. (b) 118. (a) 4. (c) 27. (a) 50. (a) 73. (d) 96. (b) 119. (d) 5. (c) 28. (c) 51. (b) 74. (b) 97. (d) 120. (d) 6. (a) 29. (b) 52. (d) 75. (c) 98. (c) 121. (b) 7. (b) 30. (d) 53. (a) 76. (b) 99. (c) 122. (d) 8. (b) 31. (b) 54. (c) 77. (d) 100. (d) 123. (b) 9. (d) 32. (b) 55. (c) 78. (c) 101. (a) 124. (b) 10. (d) 33. (d) 56. (b) 79. (d) 102. (c) 125. (c) 11. (c) 34. (b) 57. (c) 80. (d) 103. (d) 126. (a) 12. (c) 35. (c) 58. (c) 81. (b) 104. (b) 127. (a) 13. (d) 36. (b) 59. (b) 82. (a) 105. (c) 128. (b) 14. (d) 37. (b) 60. (b) 83. (c) 106. (d) 129. (d) 15. (b) 38. (d) 61. (c) 84. (b) 107. (a) 130. (c) 16. (b) 39. (b) 62. (a) 85. (d) 108. (c) 131. (b) 17. (b) 40. (c) 63. (b) 86. (c) 109. (b) 132. (d) 18. (b) 41. (c) 64. (d) 87. (b) 110. (c) 133. (b) 19. (c) 42. (d) 65. (c) 88. (d) 111. (c) 134. (b) 20. (d) 43. (d) 66. (c) 89. (c) 112. (b) 135. (d) 21. (d) 44. (c) 67. (c) 90. (b) 113. (b) 136. -

Effect of Aluminum Addition on Properties of Hadfield Steel (IJSTE/ Volume 4 / Issue 11 / 009)

IJSTE - International Journal of Science Technology & Engineering | Volume 4 | Issue 11 | May 2018 ISSN (online): 2349-784X Effect of Aluminum Addition on Properties of Hadfield Steel Chintan Miyani U.G. Student RNGPIT (FETR), Isroli-Bardoli, Gujarat, India Abstract Many studies about Hadfield steel (high Manganese austenitic steels) have been done and it was found that there are some unique characteristics of Hadfield steel which makes it more applicable. The present investigation is directed towards the effects of Aluminum addition on properties of Hadfield steel. Aluminum is added to Hadfield steel as an alloying element and different test specimens with different composition of aluminum have been examined by means of microstructure, grain size, spectroscopy, hardness, and tensile strength. Keywords: Aluminum, Hardness, Manganese, Microstructure, Tensile ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ I. INTRODUCTION Hadfield manganese steel was invented by Sir Robert Hadfield in the year of 1882 and first patented in Britain in 1883 and in 1884 the patents 303150 and 303151 were granted in the United States. In accordance with ASTM - A128 specification, the basic chemical composition of Hadfield steel is 1 - 1.4% carbon and 11 - 14% manganese. In the Hadfield steel the manganese to carbon ratio is optimum at 10:1 to ensure an austenitic microstructure after quenching. [1] Manganese acts as an austenite stabilizer and delays isothermal transformation to bainite (tempered martensite). In Hadfield steel, carbon is dissolved in austenite up to a practical limit of 1.2%. Above 1.2% carbides precipitate and separation to grain boundaries, resulting in compromised strength and ductility particularly in heavy sections. Although manganese content has little effect on yield strength, it does affect ductility and ultimate tensile strength (UTS). -

Steels Used Onboard Ships and How to Perform Maintenance Welding

TECHNICAL UPDATE TE Andersen Consulting. Steels used onboard ships and how to perform maintenance welding Despite many new materials being introduced into shipbuilding, steel is still what most ships are built from and is the most common metal that the welder onboard will encounter during maintenance welding. In below article the different kind of steels found onboard are briefly mentioned followed by application area and type of welding consumable to be used. INDEX: Classification of steel 2 Unalloyed steel (mild steel) 3 Low alloy steel 3 High tensile shipbuilding steels 3 Electrodes for unalloyed and low alloyed steels 6 Cast steel 11 Low temperature steel (cryogenic steels) 13 Weathering steel 15 Heat resistant steel (High temperature steel/ Heat- Creep resistant steel) 17 Hardox steel 21 High alloy steel 25 Stainless steel (See: Technical update- How to weld Stainless steel) Manganese steel 25 Problem steel/difficult to weld steel 26 Type of current and Amperage setting 27 Edge preparation and weld sequence 28 1 TECHNICAL UPDATE TE Andersen Consulting. Classification of steel Steel can be generally classified as an alloy of Ferrum (Fe), better known as iron, and carbon (C). Ferrum is the main component in most types of steel. Steel is classified in three grades: • Unalloyed steel containing up to 1% alloy elements. This type of steel is also termed mild steel, black steel, carbon steel, low carbon steel, non-alloyed steel and carbon manganese steel. In the following Unalloyed steel will be used as name to describe this type of steels. • Low alloy steel containing 1–5% alloy elements. -

6497421817* Soft Clean Eraser Soft Pencil (Type B Or HB Recommended)

Cambridge International Examinations Cambridge Ordinary Level CHEMISTRY 5070/11 Paper 1 Multiple Choice October/November 2016 1 hour Additional Materials: Multiple Choice Answer Sheet *6497421817* Soft clean eraser Soft pencil (type B or HB recommended) READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST Write in soft pencil. Do not use staples, paper clips, glue or correction fluid. Write your name, Centre number and candidate number on the Answer Sheet in the spaces provided unless this has been done for you. DO NOT WRITE IN ANY BARCODES. There are forty questions on this paper. Answer all questions. For each question there are four possible answers A, B, C and D. Choose the one you consider correct and record your choice in soft pencil on the separate Answer Sheet. Read the instructions on the Answer Sheet very carefully. Each correct answer will score one mark. A mark will not be deducted for a wrong answer. Any rough working should be done in this booklet. A copy of the Periodic Table is printed on page 16. Electronic calculators may be used. This document consists of 15 printed pages and 1 blank page. IB16 11_5070_11/6RP © UCLES 2016 [Turn over 2 1 A student is given only the nucleon number of an atom. What can be deduced about the structure of the atom? A number of neutrons plus protons B number of neutrons only C number of protons plus electrons D number of protons only 2 Two experiments were carried out. In experiment 1, ammonium carbonate was reacted with dilute hydrochloric acid. In experiment 2, ammonium carbonate was heated with aqueous sodium hydroxide.