Walking Track Management Strategy for Tasmania’S National Parks and Reserves 2011 - 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overland Track Terms and Conditions

Terms and Conditions Overland Track Individual Booking System These terms and conditions form an agreement carry your Overland Track Pass and Tasmanian National Parks between Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service (PWS) Pass with you as you walk, and have them readily accessible and all walkers booking their walk on the Overland for inspection by an Overland Track Ranger. Track. By accepting a booking on the Overland Track, 2. PRICING STRUCTURE AND CONCESSIONS you (the walker) agree to be bound by the terms and The current pricing structure (Australian dollars) is as listed conditions described below. at www.overlandtrack.com.au/booking. You will be walking in a wilderness area of a national park. You understand and accept that there are potential dangers Child concession (5-17 yrs) and you are undertaking such an activity at your own risk. A 20% discount is offered for walkers aged from 5 to 17 years. You acknowledge and agree that you will undertake the We don’t recommend the track for children under the age of 8, walk voluntarily and absolutely at your own risk, with a full as it’s very important they are physically and mentally able to appreciation of the nature and extent of all risks involved in the cope, and are well-equipped. walk and will be properly prepared and equipped. PWS will not Applications may be made on behalf of Children provided that: be held responsible for any injury that may occur to yourself or any member of your walking party while using the track. (i) they must be accompanied by a person over the age of 18 years when undertaking the Overland Track; 1.BOOKING AND PAYING FOR YOUR WALK (ii) that person cannot be responsible for any more than Booking your departure date on the track and paying for your a total of 3 Children walk is essential during the booking season, from 1 October to (iii) that person will be fully responsible for the care, control 31 May inclusive. -

Tasmania Road Trip

Tasmania Road Trip - 14 night self-drive tour including car and accommodation Spend 14 nights touring Tasmania – experience the best of the pristine wilderness, forever changing landscape and the fine food and beverages that make Tasmania an unforgettable experience. 14 nights allow you to take the time to get to relax and experience all regions. Base yourself in special parts of Tasmania for a few days to really immerse yourself. All holiday packages are tailor made to suit your individual requirements and tastes and include areas such as cosmopolitan Hobart, the wild West Coast, famous Cradle Mountain, far North West, the wine region of Launceston Tamar Valley and the magnificent East Coast which boasts some of the best beaches in the world! The 14 night Road Trip package includes: • 14 nights accommodation staying with TasVillas statewide. • 14 days all inclusive economy manual car hire from Budget – ensuring no costly hidden extras! • A National Parks Pass valued at $60, providing free access into statewide parks – you’re going to need it! • A quality touring map of Tasmania. • The statewide visitor guides to Tasmania, providing a range of local maps and a huge range of suggested activities and attractions. • Free Tassie Dining Card – offering discounts at local cafes and restaurants. • A bottle of Tasmanian Sparkling Janz Great Value from only $1239* per person twin share For bookings and enquiries contact Holidays Direct 1300 300 633 www.holidaysdirect.com.au ___________________________________________ *Conditions apply, subject to availability. Valid for travel between 01.09.10 and 23.12.10. Price is per person, twin share. -

The Absolute Best Day Walks in Tasmania

FOOTSTEPS WALKING CLUB OF AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND THE ABSOLUTE BEST DAY WALKS IN TASMANIA Thursday 17 March to Sunday 10 April 2022 25 days ex-Hobart (including 2 rest days) (timed to get the best weather and avoid the Tasmanian school holidays) Leader: Phillip Donnell Estimated price: $4995 (excluding airfares) (based on a minimum of 10 participants and subject to currency fluctuations) A comprehensive walking tour covering the whole of Tasmania. Experience a tremendous range of landscapes across 14 national parks, all four coasts, numerous reserves and several wilderness areas. Encounter the wildlife, discover the convict past and enjoy Tassie’s relaxed style! This is a beaut little holiday... PRICE INCLUDES: Accommodation – shared rooms in hotels, cabins, hostels, motels. Transport in a hired minibus, possibly with luggage trailer. All breakfasts and subsidised farewell celebration dinner. Experienced Kiwi trip leader throughout. National Park entry fees. Ferry fares (vehicles and passengers). PRICE DOES NOT INCLUDE: Flights to / from Tasmania (direct flights are now available). Airport transfer fees. Lunches and dinners. Travel insurance. Personal incidentals, excursions, and entry to attractions. Cradle Mountain A “White Knight” at Evercreech Wineglass Bay TASMANIA 2022 ITINERARY DATE POSSIBLE WALK(S) OVERNIGHT HOBART Day 1 Arrival Day Hobart Thursday It is recommended that you fly into Hobart early. 17 March Transfer to the hotel in downtown. Use any free time to explore Hobart: Battery Point, Queen’s Domain, MONA. A wander through the Battery Point historic area of Hobart reveals the delightful original cottages, beautiful stone and brick homes and also the maritime history of this very walkable city. -

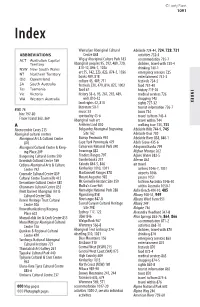

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 311 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feed- back goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. particularly Mark, Cath, Fred, Lucy and the kids OUR READERS in Hobart, and Helen in Launceston. Special Many thanks to the travellers who used thanks as always to Meg, my road-trippin’ the last edition and wrote to us with help- sweetheart, and our daughters Ione and Remy ful hints, useful advice and interesting who provided countless laughs, unscheduled anecdotes: pit-stops and ground-level perspectives along Brian Rieusset, David Thames, Garry the way. Greenwood, Jan Lehmann, Janice Blakebrough, Jon & Linley Dodd, Kevin Callaghan, Lisa Meg Worby Walker, Megan McKay, Melanie Tait, Owen A big thank you to Tasmin, once again. -

QUEEN VICTORIA MUSEUM and ART GALLERY CHS120 LLOYD JONES COLLECTION Aviator, Tasmania Photographer, Tasmania INTRODUCTION the RE

QUEEN VICTORIA MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY CHS120 LLOYD JONES COLLECTION Aviator, Tasmania Photographer, Tasmania INTRODUCTION THE RECORDS 1.Correspondence 2.Newspaper cuttings 3.Pilot’s Log Books and Certificates 4.35 mmm slides 5.Photographs 6.Publications 7.Artworks 8.Ephemera 9.Audiotape OTHER SOURCES 21/06/2017 INTRODUCTION Lloyd Lindsay Jones was born in Devonport, Tasmania on 13 May 1916, the son of Robert Ambrose Jones and Vera Maggie Jones. He was educated at Launceston High School where he served as a prefect. In 1934 he won the Hemingway and Robertson Scholarship. 1 At that time he had completed a commercial course at Launceston High School and was proceeding further with accountancy studies. After leaving school Lloyd worked at D & W Murray wholesale and supply company in both Hobart and Launceston. He joined the 40th Battalion in 19392 and from May 1942 to November 1945 served with the RAAF attached to 90 and 92 Squadrons3. He became an instructor in the Central Flying School and from this time onwards flying became his life. On 12 April 1941 Lloyd Jones married Athalie Jean Flint of Hobart in Hobart. They had three daughters. Instrumental in forming the Southern branch of the Tasmanian Aero Club in 1945 he was subsequently appointed Manager and Chief Flying Instructor of the newly formed Aero Club of Southern Tasmania in 1948. An accident at Cambridge airport in July 1960 left him with serious injuries and curtailed his flying career. At that time he had clocked up 10,776 hours flying time. 4 An adventurous and skilled pilot, Lloyd Jones was the first photographer/pilot to take aerial photographs of the rugged mountains, lakes and beaches of South West Tasmania. -

Background Report

Gordonvale World Heritage Area Reserve Background Report www.tasland.org.au Tasmanian Land Conservancy (2015). Gordonvale World Heritage Area Reserve Background Report. Tasmanian Land Conservancy, Tasmania Australia 7005. Copyright ©Tasmanian Land Conservancy The views expressed in this report are those of the Tasmanian Land Conservancy and not the Commonwealth Government, State Government or any other entity. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgment of the sources and no commercial usage or sale. Requests and enquires concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Tasmanian Land Conservancy. Front Image: Gordonvale homestead (archive photo) and the Vale of Rasselas landscape © Grant Dixon Contact Address Tasmanian Land Conservancy PO Box 2112, Lower Sandy Bay, 827 Sandy Bay Road, Sandy Bay Tasmania, AUSTRALIA 7005 | p: 03 6225 1399 | www.tasland.org.au | Contents Page Acknowledgments 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 3 INTRODUCTION 4 Gordonvale Fundraising Campaign 4 Location and Access 5 BIOREGIONAL AND LANDSCAPE CONTEXT 7 WORLD HERITAGE AREA STATUS 7 IUCN Protected Area Management Category 7 Legal Status and Compliance 8 NATURAL VALUES 9 GEO-CONSERVATION VALUES 12 WILDERNESS VALUES 12 INDIGENOUS VALUES 12 EUROPEAN HERITAGE 13 INVASIVE PESTS, WEEDS AND DISEASES 13 SCIENTIFIC STUDIES 13 MANAGEMENT STRATEGY 14 REFERENCES 15 APPENDIX A – Gordonvale ‘For Sale’ 16 APPENDIX B - Bushwalking tracks into Gordonvale 18 APPENDIX C - History of Ernie Bond at Gordonvale 21 1 Acknowledgements The Gordonvale World Heritage Area Reserve was secured by the Tasmanian Land Conservancy (TLC) in 2013 after a successful public fundraising campaign to purchase this private freehold block of land. -

January 2020

DERWENT VALLEY COUNCIL NEWS Issue 6 - January 2020 COMMUNITY GRANTS Each year, Council provides funding to community CONGRATULATIONS TO groups through its Community Grants Program, Round One of the Community Small Grants Program awarding more than $230,000 since the Community 2019/2020 awarded seven grants to community groups Small Grants Program started in 1997. and organisations, with $14,000* of budgeted funds remaining for Round Two. Grants are available to Derwent Valley based, not for profit organisations for projects that provide a benefit Lachlan Hall Committee - $792 for the replacement of within the local community. Council encourages groups kitchen floor coverings who are completing an application to read the policy guidelines, ensure they have no outstanding acquittals Derwent Valley Choir - $400 for new music scores due, complete all sections of the application form and include letters of support. Upper Derwent United Hall Inc. - $500 for whipper snipper Round Two closes 5pm Tuesday, 11 February 2020. Derwent Valley State Emergency Service - $2,000 to To assist applicants with Grant policy, guidelines and purchase a rescue training dummy applications, Council will be running a free info session. This session is for both new and previous applicants, and Westerway Primary School for $1,000 for 100th is an opportunity to ensure your submissions are strong Anniversary event activities and ask any questions you may have. Derwent Valley Arts - $1,199 for an outdoor data This session will be held from 12.30pm - 1.30pm, Tuesday projector 21 January in the Council Social Rooms. Registration is not necessary. *New Norfolk Neighbourhood Watch were previously approved for a grant of $3,025, with the condition that further funding was Questions and enquiries about applications can be acquired. -

A Review of Natural Values Within the 2013 Extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area

A review of natural values within the 2013 extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Nature Conservation Report 2017/6 Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Hobart A review of natural values within the 2013 extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Jayne Balmer, Jason Bradbury, Karen Richards, Tim Rudman, Micah Visoiu, Shannon Troy and Naomi Lawrence. Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Nature Conservation Report 2017/6, September 2017 This report was prepared under the direction of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (World Heritage Program). Australian Government funds were contributed to the project through the World Heritage Area program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Tasmanian or Australian Governments. ISSN 1441-0680 Copyright 2017 Crown in right of State of Tasmania Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright act, no part may be reproduced by any means without permission from the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Published by Natural Values Conservation Branch Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment GPO Box 44 Hobart, Tasmania, 7001 Front Cover Photograph of Eucalyptus regnans tall forest in the Styx Valley: Rob Blakers Cite as: Balmer, J., Bradbury, J., Richards, K., Rudman, T., Visoiu, M., Troy, S. and Lawrence, N. 2017. A review of natural values within the 2013 extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Nature Conservation Report 2017/6, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Hobart. -

Review of the Upper Parmeener Supergroup

IJRJ981_0i .M Tasmania Department of Mines - Report 1987/01 Review of the Upper Parmeener Supergroup by S. M. Forsyth INTRODUCTION intrude Parmeener Strata, largely as transgressive sheets and dykes several hundred metres thick (Schmidt and Strata of Late Carboniferous to Late Triassic age are McDougall, 1977; Leaman, 1975) Metamorphism caused widespread in Tasmania. The strata are essentially by the intrusions is minimal, but disruption of the host flat -lying and were named the Panneener Supergroup by strata particularly above feeders and at steeply Banks (1973). The Panneener Supergroup has been transgressive sheet segments and at junctions of intrusion formally subdivided into a Lower division that includes segments, caused significant breaks in the continuity of all known glaciomarine strata and an Upper division that lithological units. Further disruption of the strata has been consists of freshwater strata (Forsyth et al.,1974). caused by subsequent block faulting. Erosion has Strata of the Parmeener Supergroup rest (commonly with completely removed the Parmeener strata from some area. pronounced landscape unconformity) or granitic and The uppennost strata tend to be preserved only in graberts folded rocks. They obtain a maximum composite or where Jurassic dolerite sheets or Tertiary basalt flows thickness of about 2 Ian. Most of the initial basement have slowed erosion. irregularities were buried during deposition of the Lower This review deals largely with the stratigraphy and Parmeener Supergroup. Local disconfonnities, very palaeontology of the Upper Parmeener Supergroup and is slightly angular erosive unconformities and condensed an expanded version of the section on the stratigraphy of sequences indicate surface subsidence was not entirely the Upper Parmeener Supergroup in the Geology and unifonn during deposition of the Parmeener Supergroup MineraIDepositsofTasmania(BurrettandMartin,1989). -

3966 Tour Op 4Col

The Tasmanian Advantage natural and cultural features of Tasmania a resource manual aimed at developing knowledge and interpretive skills specific to Tasmania Contents 1 INTRODUCTION The aim of the manual Notesheets & how to use them Interpretation tips & useful references Minimal impact tourism 2 TASMANIA IN BRIEF Location Size Climate Population National parks Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) Marine reserves Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) 4 INTERPRETATION AND TIPS Background What is interpretation? What is the aim of your operation? Principles of interpretation Planning to interpret Conducting your tour Research your content Manage the potential risks Evaluate your tour Commercial operators information 5 NATURAL ADVANTAGE Antarctic connection Geodiversity Marine environment Plant communities Threatened fauna species Mammals Birds Reptiles Freshwater fishes Invertebrates Fire Threats 6 HERITAGE Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage European history Convicts Whaling Pining Mining Coastal fishing Inland fishing History of the parks service History of forestry History of hydro electric power Gordon below Franklin dam controversy 6 WHAT AND WHERE: EAST & NORTHEAST National parks Reserved areas Great short walks Tasmanian trail Snippets of history What’s in a name? 7 WHAT AND WHERE: SOUTH & CENTRAL PLATEAU 8 WHAT AND WHERE: WEST & NORTHWEST 9 REFERENCES Useful references List of notesheets 10 NOTESHEETS: FAUNA Wildlife, Living with wildlife, Caring for nature, Threatened species, Threats 11 NOTESHEETS: PARKS & PLACES Parks & places, -

World Heritage Values and to Identify New Values

FLORISTIC VALUES OF THE TASMANIAN WILDERNESS WORLD HERITAGE AREA J. Balmer, J. Whinam, J. Kelman, J.B. Kirkpatrick & E. Lazarus Nature Conservation Branch Report October 2004 This report was prepared under the direction of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment (World Heritage Area Vegetation Program). Commonwealth Government funds were contributed to the project through the World Heritage Area program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment or those of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. ISSN 1441–0680 Copyright 2003 Crown in right of State of Tasmania Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any means without permission from the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment. Published by Nature Conservation Branch Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment GPO Box 44 Hobart Tasmania, 7001 Front Cover Photograph: Alpine bolster heath (1050 metres) at Mt Anne. Stunted Nothofagus cunninghamii is shrouded in mist with Richea pandanifolia scattered throughout and Astelia alpina in the foreground. Photograph taken by Grant Dixon Back Cover Photograph: Nothofagus gunnii leaf with fossil imprint in deposits dating from 35-40 million years ago: Photograph taken by Greg Jordan Cite as: Balmer J., Whinam J., Kelman J., Kirkpatrick J.B. & Lazarus E. (2004) A review of the floristic values of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Nature Conservation Report 2004/3. Department of Primary Industries Water and Environment, Tasmania, Australia T ABLE OF C ONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................................1 1.