Dear Colleagues, the Following Is a Draft of a Chapter of My Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of Exporters of Primorsky Krai № ITN/TIN Company Name Address OKVED Code Kind of Activity Country of Export 1 254308

Catalogue of exporters of Primorsky krai № ITN/TIN Company name Address OKVED Code Kind of activity Country of export 690002, Primorsky KRAI, 1 2543082433 KOR GROUP LLC CITY VLADIVOSTOK, PR-T OKVED:51.38 Wholesale of other food products Vietnam OSTRYAKOVA 5G, OF. 94 690001, PRIMORSKY KRAI, 2 2536266550 LLC "SEIKO" VLADIVOSTOK, STR. OKVED:51.7 Other ratailing China TUNGUS, 17, K.1 690003, PRIMORSKY KRAI, VLADIVOSTOK, 3 2531010610 LLC "FORTUNA" OKVED: 46.9 Wholesale trade in specialized stores China STREET UPPERPORTOVA, 38- 101 690003, Primorsky Krai, Vladivostok, Other activities auxiliary related to 4 2540172745 TEK ALVADIS LLC OKVED: 52.29 Panama Verkhneportovaya street, 38, office transportation 301 p-303 p 690088, PRIMORSKY KRAI, Wholesale trade of cars and light 5 2537074970 AVTOTRADING LLC Vladivostok, Zhigura, 46 OKVED: 45.11.1 USA motor vehicles 9KV JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 690091, Primorsky KRAI, Processing and preserving of fish and 6 2504001293 HOLDING COMPANY " Vladivostok, Pologaya Street, 53, OKVED:15.2 China seafood DALMOREPRODUKT " office 308 JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 692760, Primorsky Krai, Non-scheduled air freight 7 2502018358 OKVED:62.20.2 Moldova "AVIALIFT VLADIVOSTOK" CITYARTEM, MKR-N ORBIT, 4 transport 690039, PRIMORSKY KRAI JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 8 2543127290 VLADIVOSTOK, 16A-19 KIROV OKVED:27.42 Aluminum production Japan "ANKUVER" STR. 692760, EDGE OF PRIMORSKY Activities of catering establishments KRAI, for other types of catering JOINT-STOCK COMPANY CITYARTEM, STR. VLADIMIR 9 2502040579 "AEROMAR-ДВ" SAIBEL, 41 OKVED:56.29 China Production of bread and pastry, cakes 690014, Primorsky Krai, and pastries short-term storage JOINT-STOCK COMPANY VLADIVOSTOK, STR. PEOPLE 10 2504001550 "VLADHLEB" AVENUE 29 OKVED:10.71 China JOINT-STOCK COMPANY " MINING- METALLURGICAL 692446, PRIMORSKY KRAI COMPLEX DALNEGORSK AVENUE 50 Mining and processing of lead-zinc 11 2505008358 " DALPOLIMETALL " SUMMER OCTOBER 93 OKVED:07.29.5 ore Republic of Korea 692183, PRIMORSKY KRAI KRAI, KRASNOARMEYSKIY DISTRICT, JOINT-STOCK COMPANY " P. -

Modern Specialization of Industry in Cities of the Russian Far East: Innovation Factor of Dynamics

ISSN 0798 1015 HOME Revista ESPACIOS ! ÍNDICES ! A LOS AUTORES ! Vol. 38 (Nº 62) Year 2017. Páge 29 Modern Specialization of Industry in Cities of the Russian Far East: Innovation Factor of Dynamics Especialización moderna de la industria en las ciudades del Lejano Oriente ruso: factor de innovación dinámica Viktor Alekseevich OSIPOV 1; Elena Viktorovna KRASOVA 2 Received: 06/10/2017 • Approved: 30/10/2017 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Methods 3. Results 4. Discussion 5. Conclusion References ABSTRACT: RESUMEN: Industrial specialization of the Russian Far Eastern cities is one La especialización industrial de las ciudades rusas del Lejano of the most urgent topics of the Russian researches in such Oriente es uno de los temas más urgentes de las areas as industry economy, efficiency of using industrial investigaciones rusas en áreas como la economía industrial, la productive sources, regional economy, and innovation eficiencia en el uso de fuentes productivas industriales, la economy. The main science and practice challenge of the economía regional y la economía de la innovación. El principal research is the problems that restrain the transition of industry desafío científico y práctico de la investigación son los in Russian Far Eastern cities to the innovation economy. The problemas que restringen la transición de la industria en las goal of the article is to update on the problems of the modern ciudades rusas del Lejano Oriente hacia la economía de la specialization of Far Eastern cities taking into account the innovación. El objetivo del artículo es actualizar los problemas innovation factor of the regional economy development. de la especialización moderna de las ciudades del Lejano Methodologically the article is based on general provisions of Oriente tomando en cuenta el factor de innovación del the modern economic science, particularly, the theory of desarrollo de la economía regional. -

A Garrison in Time Saves Nine

1 A Garrison in Time Saves Nine: Frontier Administration and ‘Drawing In’ the Yafahan Orochen in Late Qing Heilongjiang Loretta E. Kim The University of Hong Kong [email protected] Abstract In 1882 the Qing dynasty government established the Xing’an garrison in Heilongjiang to counteract the impact of Russian exploration and territorial expansion into the region. The Xing’an garrison was only operative for twelve years before closing down. What may seem to be an unmitigated failure of military and civil administrative planning was in fact a decisive attempt to contend with the challenges of governing borderland people rather than merely shoring up physical territorial limits. The Xing’an garrison arose out of the need to “draw in” the Yafahan Orochen population, one that had developed close relations with Russians through trade and social interaction. This article demonstrates that while building a garrison did not achieve the intended goal of strengthening control over the Yafahan Orochen, it was one of several measures the Qing employed to shape the human frontier in this critical borderland. Keywords 1 2 Butha, Eight Banners, frontier administration, Heilongjiang, Orochen Introduction In 1882, the Heilongjiang general’s yamen began setting up a new garrison. This milestone was distinctive because 150 years had passed since the last two were established, which had brought the actual total of garrisons within Heilongjiang to six.. The new Xing’an garrison (Xing’an cheng 興安城) would not be the last one built before the end of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) but it was notably short-lived, in operation for only twelve years before being dismantled. -

Revolution, War and Imperial Conflict in Blagoveshchensk-Heihe Yuexin Rachel Lin

“We Are on the Brink of Disaster”: Revolution, War and Imperial Conflict in Blagoveshchensk-Heihe Yuexin Rachel Lin When Russian imperial power extended to the Amur in the mid-19th Century, Blagoveshchensk- Heihe became one of the foremost sites of imperial competition. The proximity of the Chinese and Russian cities, within sight of each other across the Amur River, engendered both connection and conflict, while the strategic waterway attracted Japanese trade. Some of the starkest manifesta- tions of Sino-Russian conflict had erupted there, including the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and the 1900 massacre of Chinese during the Boxer Rebellion. Control over Chinese migration became a peren- nial problem - which led to the deeply-resented river-crossing permit regime - and Japanese inter- est in commerce and shipping challenged both Russian and Chinese interests. Historical memories of such conflict persisted even as the Qing and tsarist regimes collapsed. They were brought to the fore by the arrival of the 1917 Russian Revolution, when the collapse of Russian state power offered the opportunity to recover past losses. This paper examines the vio- lence of the revolutionary and Civil War period in Blagoveshchensk-Heihe from the perspective of the Chinese community in both cities. It focuses on key economic and political actors — diaspora leaders and border officials — who formed self-defence organisations, appealed for greater military and diplomatic presence in Russian territory, and warned of Japanese opportunism on the Amur. In so doing, they appealed to emotive “moments” in Sino-Russian historical memory, particularly the Aigun Treaty and the Blagoveshchensk massacre. Therefore, this paper argues that the revolu- tionary upheavals in Russia fed into long-term discourses of Sino-Russian conflict, and that shared historical memories enabled disparate groups to take part in revisionist activism. -

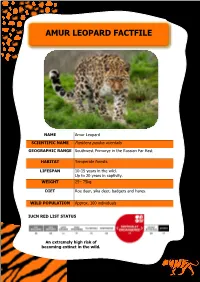

Amur Leopard Fact File

AMUR LEOPARD FACTFILE NAME Amur Leopard SCIENTIFIC NAME Panthera pardus orientalis GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwest Primorye in the Russian Far East HABITAT Temperate forests. LIFESPAN 10-15 years in the wild. Up to 20 years in captivity. WEIGHT 25– 75kg DIET Roe deer, sika deer, badgers and hares. WILD POPULATION Approx. 100 individuals IUCN RED LIST STATUS An extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild. GENERAL DESCRIPTION Amur leopards are one of nine sub-species of leopard. They are the most critically endangered big cat in the world. Found in the Russian far-east, Amur leopards are well adapted to a cold climate with thick fur that can reach up to 7.5cm long in winter months. Amur leopards are much paler than other leopards, with bigger and more spaced out rosettes. This is to allow them to camouflage in the snow. In the 20th century the Amur leopard population dramatically decreased due to habitat loss and hunting. Prior to this their range extended throughout northeast China, the Korean peninsula and the Primorsky Krai region of Russia. Now the Amur leopard range is predominantly in the south of the Primorsky Krai region in Russia, however, individuals have been reported over the border into northeast China. In 2011 Amur leopard population estimates were extremely low with approximately 35 individuals remaining. Intensified protection of this species has lead to a population increase, with approximately 100 now remaining in the wild. AMUR LEOPARD RANGE THREATS • Illegal wildlife trade– poaching for furs, teeth and bones is a huge threat to Amur leopards. A hunting culture, for both sport and food across Russia, also targets the leopards and their prey species. -

How the Chinese See Russia

How the Chinese See Russia Bobo Lo December 2010 Russia/NIS Center Ifri is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debates and research activities. The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ alone and do not reflect the official views of their institutions. Russia/NIS Center © All rights reserved – Ifri – Paris, 2010 ISBN: 978-2-86592-809-5 IFRI IFRI-Bruxelles 27 RUE DE LA PROCESSION RUE MARIE-THERESE, 21 75740 PARIS CEDEX 15 – FRANCE 1000 BRUXELLES TEL. : 33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 TEL. : 32(2) 238 51 10 FAX : 33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 FAX : 32 (2) 238 51 15 E-MAIL : [email protected] E-MAIL : [email protected] WEBSITE : www.ifri.org B. Lo / Chinese Perceptions of Russia Executive Summary China is in the midst of one of the most remarkable transformations in history. In its search for economic development and industrial modernization, Chinese policy-makers look to the West for their points of reference. Russia, which once offered an alternative model, now stands as an object lesson in what not to do. -

Tracing Population Movements in Ancient East Asia Through the Linguistics and Archaeology of Textile Production

Evolutionary Human Sciences (2020), 2, e5, page 1 of 20 doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.4 REVIEW Tracing population movements in ancient East Asia through the linguistics and archaeology of textile production Sarah Nelson1, Irina Zhushchikhovskaya2, Tao Li3,4, Mark Hudson3 and Martine Robbeets3* 1Department of Anthropology, University of Denver, Denver, CO, USA, 2Laboratory of Medieval Archaeology, Institute of History, Archaeology and Ethnography of Peoples of Far East, Far Eastern Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok, Russia, 3Eurasia3angle Research group, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany and 4Department of Archaeology, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Archaeolinguistics, a field which combines language reconstruction and archaeology as a source of infor- mation on human prehistory, has much to offer to deepen our understanding of the Neolithic and Bronze Age in Northeast Asia. So far, integrated comparative analyses of words and tools for textile production are completely lacking for the Northeast Asian Neolithic and Bronze Age. To remedy this situation, here we integrate linguistic and archaeological evidence of textile production, with the aim of shedding light on ancient population movements in Northeast China, the Russian Far East, Korea and Japan. We show that the transition to more sophisticated textile technology in these regions can be associated not only with the adoption of millet agriculture but also with the spread of the languages of the so-called ‘Transeurasian’ family. In this way, our research provides indirect support for the Language/Farming Dispersal Hypothesis, which posits that language expansion from the Neolithic onwards was often associated with agricultural colonization. -

Amur Oblast TYNDINSKY 361,900 Sq

AMUR 196 Ⅲ THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST SAKHA Map 5.1 Ust-Nyukzha Amur Oblast TY NDINS KY 361,900 sq. km Lopcha Lapri Ust-Urkima Baikal-Amur Mainline Tynda CHITA !. ZEISKY Kirovsky Kirovsky Zeiskoe Zolotaya Gora Reservoir Takhtamygda Solovyovsk Urkan Urusha !Skovorodino KHABAROVSK Erofei Pavlovich Never SKOVO MAGDAGACHINSKY Tra ns-Siberian Railroad DIRO Taldan Mokhe NSKY Zeya .! Ignashino Ivanovka Dzhalinda Ovsyanka ! Pioner Magdagachi Beketovo Yasny Tolbuzino Yubileiny Tokur Ekimchan Tygda Inzhan Oktyabrskiy Lukachek Zlatoustovsk Koboldo Ushumun Stoiba Ivanovskoe Chernyaevo Sivaki Ogodzha Ust-Tygda Selemdzhinsk Kuznetsovo Byssa Fevralsk KY Kukhterin-Lug NS Mukhino Tu Novorossiika Norsk M DHI Chagoyan Maisky SELE Novovoskresenovka SKY N OV ! Shimanovsk Uglovoe MAZ SHIMA ANOV Novogeorgievka Y Novokievsky Uval SK EN SK Mazanovo Y SVOBODN Chernigovka !. Svobodny Margaritovka e CHINA Kostyukovka inlin SERYSHEVSKY ! Seryshevo Belogorsk ROMNENSKY rMa Bolshaya Sazanka !. Shiroky Log - Amu BELOGORSKY Pridorozhnoe BLAGOVESHCHENSKY Romny Baikal Pozdeevka Berezovka Novotroitskoe IVANOVSKY Ekaterinoslavka Y Cheugda Ivanovka Talakan BRSKY SKY P! O KTYA INSK EI BLAGOVESHCHENSK Tambovka ZavitinskIT BUR ! Bakhirevo ZAV T A M B OVSKY Muravyovka Raichikhinsk ! ! VKONSTANTINO SKY Poyarkovo Progress ARKHARINSKY Konstantinovka Arkhara ! Gribovka M LIKHAI O VSKY ¯ Kundur Innokentevka Leninskoe km A m Trans -Siberianad Railro u 100 r R i v JAO Russian Far East e r By Newell and Zhou / Sources: Ministry of Natural Resources, 2002; ESRI, 2002. Newell, J. 2004. The Russian Far East: A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development. McKinleyville, CA: Daniel & Daniel. 466 pages CHAPTER 5 Amur Oblast Location Amur Oblast, in the upper and middle Amur River basin, is 8,000 km east of Moscow by rail (or 6,500 km by air). -

Downloaded340090 from Brill.Com09/30/2021 10:01:22PM Via Free Access Milk, Game Or Grain for a Manchurian Outpost 241

INNER ASIA �9 (�0�7) �40–�73 Inner ASIA brill.com/inas Milk, Game or Grain for a Manchurian Outpost Providing for Hulun Buir’s Multi-Environmental Garrison in an Eighteenth-Century Borderland David Bello History Department, Washington & Lee University, USA [email protected] Abstract The long record of imperial China’s Inner Asian borderland relations is not simply multi-ethnic, but ‘multi-environmental’. Human dependencies on livestock, wild ani- mals and cereal cultivars were the prerequisite environmental relations for borderland incorporation. This paper examines such dependencies during the Qing Dynasty’s (1644–1912) establishment of the Manchurian garrison of Hulun Buir near the Qing border with Russia. Garrison logistics proved challenging because provisioning in- volved several indigenous groups—Solon-Ewenki, Bargut and Dagur (Daur)—who did not uniformly subsist on livestock, game or grain, but instead exhibited several, sometimes overlapping, practices not always confined within a single ethnicity. Ensuing deliberations reveal official convictions, some of which can be traced back to the preceding Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), regarding the variable effects of these prac- tices on the formation of Inner Asian military identities. Such issues were distinctive of Qing borderland dynamics that constructed ‘Chinese’ empire not only in more diverse human society, but also in more diverse ecological spheres. Keywords Hulun Buir – Solon – Dagur – Bargut – agro-pastoral – hunting – Qing dynasty – Manchuria – borderland – environmental relations … © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���7 | doi �0.��63/���050�8-��Downloaded340090 from Brill.com09/30/2021 10:01:22PM via free access Milk, Game or Grain for a Manchurian Outpost 241 Han farm and fight, so they are worn out and cowardly; the northern bar- barians just herd and hunt, so they are energetic and brave. -

Effects of Flood on DOM and Total Dissolved Iron Concentration in Amur River

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 21, EGU2019-11918, 2019 EGU General Assembly 2019 © Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. Effects of Flood on DOM and Total Dissolved Iron Concentration in Amur River Baixing Yan and Jiunian Guan Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Key Laboratory of Wetland Ecology and Environment, China ([email protected]) DOM is an important indicator for freshwater quality and may complex with metals. It is already found that the water quality was abnormal during or after the flood events in various areas, which may be due to the release and resuspending of sediment in the river and leaching of the soil in the river basin area. And flood are also a major pathway for different dissolved matter, such as DOM, transport into the river system from the flood bed, wetlands, etc., when the flood was subsided. River flood has visibly impact on DOM component and concentration. The concentration and species of DOM and dissolved iron during different floods, including watershed extreme flood event, typhoon-induced flood event, snow-thawed flood event were monitored in Amur River and its biggest trib- utary Songhua River. Also, some simulation experiments in lab were implemented. The samples were filtered by 0.45µm filter membrane in situ, then analyze the ionic iron (ferrous ion, Ferric ion) by ET7406 Iron Concentration Tester(Lovibond, Germany with Phenanthroline colorimetric method). The total dissolved iron was determined by GBC 906 AAS(Australia) in lab. DOC was analyzed by TOC VCPH, SHIMADZU(Japan). The results showed that DOC ranged 6.63-9.19 mg/L (averaged at 7.68 mg/L) during extreme Songhua-Amur flood event in 2013.The lower molecular weight of organic matter[U+FF08]<10kDa[U+FF09]was the dominant form of DOM, and the lower molecular weight of complex iron was the dominant form of total dissolved iron. -

History of China: Table of Contents

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century. -

Environmental Evolution of Xingkai (Khanka) Lake Since 200 Ka by OSL Dating of Sand Hills

Article Geology August 2011 Vol.56 No.24: 26042612 doi: 10.1007/s11434-011-4593-x SPECIAL TOPICS: Environmental evolution of Xingkai (Khanka) Lake since 200 ka by OSL dating of sand hills ZHU Yun1,2, SHEN Ji1*, LEI GuoLiang2 & WANG Yong1 1 Key Laboratory of Lake Science and Environment, Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; 2 College of Geographical Sciences, Fujian Normal University, Fujian Key Laboratory of Subtropical Resources and Environment, Fuzhou 350007, China Received February 28, 2011; accepted May 13, 2011 Crossing the Sino-Russian boundary, Xingkai Lake is the largest freshwater lake in Northeast Asia. In addition to the lakeshore, there are four sand hills on the north side of the lake that accumulated during a period of sustainable and stable lacustrine trans- gression and were preserved after depression. Analysis of well-dated stratigraphic sequences based on 18 OSL datings combined with multiple index analysis of six sites in the sand hills revealed that the north shoreline of Xingkai Lake retreated in a stepwise fashion since the middle Pleistocene, and that at least four transgressions (during 193–183 ka, 136–130 ka, 24–15 ka and since 3 ka) and three depressions occurred during this process. The results of this study confirmed that transgressive stages were concur- rent with epochs of climate cooling, whereas the period of regression corresponded to the climatic optima. Transgressions and regressions were primarily caused by variations in the intensity of alluvial accumulation in the Ussuri River Valley and fluctua- tions in regional temperature and humidity that were controlled by climatic change.