Facts About the School, D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 • 7 Sports Added in the Last Two Seasons Semester

A staple in the New York region and an emerging program on the national stage, the Manhattanville College Athletic Department continues to bolster its reputation as a program on the rise in all areas: athletic achievement, academic success and overall participation. A program-record 305 Valiant student-athletes (nearly 20 percent of the student body) took part in intercollegiate athletics during the 2008- 09 season, showcasing the continued and rapid growth of athletics at Manhattanville. Following the successful integration of the men’s and women’s indoor and outdoor track teams last season, the program has expanded to a record 21 intercollegiate teams – including seven new teams established in the last two years alone. And teams at Manhattanville do not just compete, they win. Three Valiant squads (men’s basketball, baseball and men’s tennis) earned Freedom Conference regular-season championships in 2008-09 and both the men’s and women’s hockey teams spent much of the year with national rankings. Sixteen of 21 Valiant teams earned berths in their respective conference tournaments last year, including four conference championship game appearances. In all, Manhattanville teams posted an impressive .548 winning percentage (184-151-6) last season, with two Valiants teams also setting new program records for wins in a single season. On an individual level, many Valiant student-athletes were honored in 2008-09 as well. Men’s hockey forward Chris Trafford and women’s hockey center Holly Nonis became the 15th and 16th Valiants to earn All-American honors following the season, while the pair were two of four players to be named conference Player of the Year. -

American Meteorological Society Award

WESEF 2018 AWARDS PAGE 3 American Meteorological Society Award Certificates are given to projects for creative scientific endeavor in the areas of atmospheric and related oceanic or hydrologic sciences. Animal Sciences Westlake High School Lee Cohen (LEE CO-EN) Animal Sciences Ossining High School Pedro Montes De Oca Jr. (PAE-DRO - MON-TEZ- DAE- OCA ) Animal Sciences Fox Lane High School Marco Zanghi (Marco Zangee) Animal Sciences Ossining High School Julia Piccirillo-Stosser Sabrina Piccirillo-Stosser Kiara Taveras (Julia Piccirillo-Stosser, Sabrina Piccirillo-Stosser, Kiara Taveras) Environmental Sciences John Jay High School Akshay Amin (Ak shay Ah mean) Environmental Sciences Pelham Memorial High School Aidan Sisk Morgan McLean Bernadette Russo (Ay-Dan Sisk) WESEF 2018 AWARDS PAGE 4 American Psychological Association Award Certificates are given to students for their outstanding research in psychological science. Behavioral and Social Byram Hills High School Cooper Gray (Coop-er Gray) Sciences Behavioral and Social Croton-Harmon High School Vishwanka Kuchibhatla (Vish-wan-ka Coo- Sciences chi-bot-la) Behavioral and Social Dobbs Ferry High School Isabel Long (Is-A-Bel Long) Sciences Behavioral and Social Yorktown High School Kayla Mariuzza (Kayyylah Mehr-ee-utsa) Sciences Behavioral and Social New Rochelle High School Jillian Stokes (JILL-e-IN Stokes) Sciences WESEF 2018 AWARDS PAGE 5 Association for Women Geoscientists Award A certificate will be awarded to female students whose projects exemplify high standards of innovativeness -

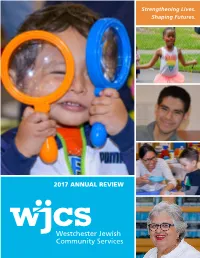

WJCS Annual Review 2017

Strengthening Lives. Shaping Futures. 2017 ANNUAL REVIEW 845 N. Broadway, White Plains, NY 10603 • 914-761-0600 • [email protected] Westchester Jewish Community Services At the Annual Gala with honorees and WJCS board members Bruce Freyer, left, and Froma Benerofe, third left, are board president Neil Sandler, second left, CEO Alan Trager, Westchester County Executive Rob Astorino and COO Bernie Kimberg. Celebrating the 35th anniversary of the pioneering Treatment Center for Trauma and Abuse now renamed Trager Lemp Center: Treating Trauma & Promoting Resilience are: from left, Deputy County Executive Kevin Plunkett; Liane Nelson, PhD, chief psychologist and director of the Trager Lemp Center; Pat Lemp, assistant executive director of clinic-based services; CEO Alan Trager; Joe Kenner, deputy commissioner, Westchester County Dept. of Social Services, and Michael Orth, Commissioner, Westchester County Department of Community Health. Presenting a generous donation to help launch “Just Me,” a new WJCS pilot program for preschoolers are Alan Waxenberg and Natalie Robinson, fifth and sixth from left, chairs of the Metropolis Country Club Foundation. With them are, from left, Susan Lewen, chief development officer; Sarah Kayle, board member; Shannon Van Loon, assistant executive director, children, youth and family services; COO Bernie Kimberg, and Vicki Forbes, director of the infant-toddler programs. WJCS INSPIRED Dear Friends: Our continued focus on trauma, and its often devastating effects on the people we serve, has allowed WJCS to During 2017, the many faces of enhance all programs through an agency-wide training initia- WJCS continued to inspire our work tive that has fortified us as a trauma-informed agency; and we to provide the highest quality men- continue our leadership throughout the county in promoting a trau- tal health, trauma, youth, geriatric, ma-informed system of care. -

In Our Schools Peekskill City School District News May 2015

SPECIAL BUDGET ISSUE In Our Schools Peekskill City School District News May 2015 Dear Peekskill Community, School Board Election On behalf of the Board of Education, we are pleased to announce that our Two three-year seats are up for election: Incumbent Lisa lobbying efforts to recover state aid resulted in a 10.5% overall increase for Aspinall-Kellawon and Incumbent Colin Smith. Voters will the Peekskill City School District. As you peruse through this newsletter, elect two members to the Peekskill City School District you will see the impact this aid will have on adding much needed programs Board of Education. and enhancing the quality of our schools. A school budget of $81,890,784 was adopted by the Board of Education on April 21, 2015, resulting in a All Individuals Must Be Qualified to Vote budget increase of 2.54% and a tax levy decrease of -2.02%. A qualified voter is a person who is a citizen of the United States, at least 18 years old, and a resident of the school In March of this school year, the Board learned that to be consistent with district for at least 30 days prior to the vote. New York State Education Law 3635, a new Transportation Proposition was needed. After careful deliberation and community input, the Board When and Where to Vote The vote on the annual budget and for school board candi- determined that in order to preserve the Princeton Plan, transportation is dates will take place on Tuesday, May 19 from 7 A.M. to 9 P.M. -

City of White Plains 2016 Guide

CITY OF WHITE PLAINS 2016 GUIDE Spring & Summer Recreation & Parks • Youth Bureau Library & Performing Arts Center Programs, Activities & Services www.cityofwhiteplains.com The City of White Plains Programs WHITE PLAINS CITY OFFICIALS Office of the Mayor Mayor City of White Plains, Office of the Mayor Thomas M. Roach 255 Main Street, White Plains NY 10601 Council President John Kirkpatrick Dear Fellow Residents: Common Council John Kirkpatrick Dennis Krolian The City of White Plains is pleased to present The Milagros Lecuona 2016 Spring/Summer Guide. The Guide details the Nadine Hunt-Robinson John Martin many programs offered by the Recreation & Parks Beth Smayda Department, White Plains Library, the Youth Bureau, the White Plains Performing Arts Center and our community partners. Recreation 2016 marks the Centennial Anniversary of the City of White Plains, New York. Advisory Please take a moment to review the Guide and mark your calendars with the many Committee John Martin, special events, new initiatives and old favorites the City has to offer during this Chairman milestone year. Celebration highlights include a performance by the highly acclaimed Christine Eifler West Point Concert Band at our annual Independence Day Celebration on July 1st at Leonard Gruenfeld White Plains High School and a special re-enactment of the first public reading of the Cayne Letizia Charles Morgan Declaration of Independence in New York State, which occurred right here in our own Richard Myers city. That event will take place on June 18th in Tibbits Park. Our popular Shakespeare Nyla Robinson in the Park will be back in July at Turnure Park and we’ll once again be offering Yoga Richard Sanchez Evelyn Santiago on Court Street on June 22nd. -

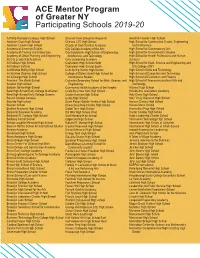

ACE Mentor Program of Greater NY Participating Schools 2019-20

ACE Mentor Program of Greater NY Participating Schools 2019-20 A.Phillip Randolph Campus High School Channel View School for Research Hendrick Hudson High School Abraham Clark High School Chelsea CTE High School High School for Construction Trades, Engineering, Abraham Lincoln High School Church of God Christian Academy and Architecture Academy of American Studies City College Academy of the Arts High School for Contemporary Arts Academy of Finance and Enterprises City Polytechnic High School of Engineering, High School for Environmental Studies Academy of Urban Planning and Engineering Architecture, and Technology High School for Health Professions and Human All City Leadership Academy Civic Leadership Academy Services All Hallows High School Clarkstown High School North High School for Math, Science and Engineering and All Hallows Institute Clarkstown High School South City College of NY Archbishop Molloy High School Cold Spring Harbor High School High School of Arts and Technology Archbishop Stepinac High School College of Staten Island High School for High School of Computers and Technology Art & Design High School International Studies High School of Economics and Finance Avenues: The World School Columbia Secondary School for Math, Science, and High School of Telecommunications Arts and Aviation High School Engineering Technology Baldwin Senior High School Community Health Academy of the Heights Hillcrest High School Bard High School Early College Manhattan Cristo Rey New York High School Hillside Arts and Letters Academy Bard High School Early College Queens Croton Harmon High School Holy Cross High School Baruch College Campus Curtis High School Holy Trinity Diocesan High School Bayside High school Davis Renov Stahler Yeshiva High School Horace Greeley High School Beacon School Democracy Prep Charter High School Horace Mann School Bedford Academy High School Digital Tech High School Humanities Prep High School Benjamin Banneker Academy Dix Hills High School West Hunter College High School Benjamin N. -

June 2017 Serving Tarrytown, Sleepy Hollow, Irvington, Scarborough-On-Hudson and Ardsley-On-Hudson Vol

[see Pages H1-H8] 3 » Bridge Contest Continues 11-13 » Heads of the Class 17 » Farmers Market Returns Your Most Trusted Source for Local News and Events June 2017 Serving Tarrytown, Sleepy Hollow, Irvington, Scarborough-on-Hudson and Ardsley-on-Hudson Vol. XII No. 6 As Completion of the New Bridge Nears, Teen Drinking Changes Are Coming Along Roadways Parties Put in the Rivertowns Parents at by Barrett Seaman Risk Te trend is clear: biking and walking are in; driving—especially at high speed—is frowned upon in the rivertowns. Encouraged by state transportation authorities in anticipation of the by Krista Madsen major changes in trafc patterns that will come with the opening of the new bridge, local mu- nicipalities are making plans to encourage the former and crack down on the latter. As the school year ends and summer par- Meetings scheduled for June in Hastings and Tarrytown will invite public opinion on the plans ties fourish, so too does underage drink- to create a seamless bike route down Broadway, from Sleepy Hollow to Hastings. Separately, Sleepy ing. Local police anticipate being busy Hollow’s Environmental Advisory Committee is planning an “Inner Village Walkability Workshop” issuing summonses to teens, but the under- on Saturday, June 10. lying problem, according to experts, is with In Irvington, the Trafc Calming Committee (pioneer of the Slowdown Rivertowns campaign) some parents. has invited 6th to 12th graders to produce short Public Service videos (60 seconds max) on “Cross- “I see this shift in parenting where they walk Safety – Stop, Look, Wave” or “Nighttime Visibility”. -

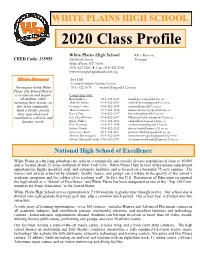

2020 Class Profile

WHITE PLAINS HIGH SCHOOL 2020 Class Profile White Plains High School Ellen Doherty CEEB Code: 335955 550 North Street Principal White Plains, NY 10605 (914) 422-2182 ♦ Fax: (914) 422-2196 www.whiteplainspublicschools.org Mission Statement Sara Hall Assistant Principal, Guidance Services The mission of the White (914) 422-3675 [email protected] Plains City School District is to educate and inspire Counseling Staff all students, while Rob Baddeley (914) 422-2424 [email protected] nurturing their dreams, so Michelle Bason (914) 422-2163 [email protected] they learn continually, Enrique Cafaro (914) 422-2149 [email protected] think critically, pursue Maria Csikortos (914) 422-2148 [email protected] their aspirations and Karen Day (914) 422-2167 [email protected] contribute to a diverse and Lily Diaz-Withers (914) 422-2147 [email protected] dynamic world. Emily Falber (914) 422-2164 [email protected] Erin Harrison (914) 422-2150 [email protected] Jeffrey Hirsch (914) 422-2232 [email protected] Genevieve Little (914) 422-2427 [email protected] Marcos Monteagudo (914) 422-2168 [email protected] Silvana Mazurek-Lazala (914) 422-2175 [email protected] National High School of Excellence White Plains is a thriving suburban city with an economically and racially diverse population of close to 50,000 and is located about 25 miles northeast of New York City. White Plains High School offers unique educational opportunities, highly qualified staff, and extensive facilities, and is located on a beautiful 75-acre campus. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 372 787 JC 940 396 TITLE Westchester

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 372 787 JC 940 396 TITLE Westchester Community College President's Report, 1991-1993. INSTITUTION Westchester Community Coll., Valhalla, N.Y. PUB DATE 15 Oct 93 NOTE 92p. PUB TYPE Statistical Data (110) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS College Administration; College Curriculum; *College Faculty; College Programs; Community Colleges; *Educational Finance; *Enrollment Trends; Facility Improvement; *Institutional Characteristics; *School Community Relationship; Student Characteristics; Two Year Colleges; *Two Year College Students IDENTIFIERS *Westchester Community College NY ABSTRACT This report by the president of Westchester Community College (WCC) in New York presents an extensive overview of the college's accomplishments and of the students, the faculty, and the finances for the period 1991-1993. After providing a brief introduction to WCC's mission, programs, facilities, and growth, the report highlights accomplishments in the areas of community leadership, academic development, administration, and campus development. Selected accomplishments include the following:(1) WCC responded to community needs by: retraining dislocated workers at the WCC Professional Development Center; training municipalities., industry, and government about waste reduction, recycling, minimalization technology and on-site bioremediation of pollutants; providing free educational services to the disadvantaged; and conferring 115 associate degrees or certificates to welfare recipients;(2) new programs -

Spring Summer

CITY OF WHITE PLAINS 2019 GUIDE Spring Summer Recreation & Parks • Youth Bureau Library & Performing Arts Center Programs, Activities & Services www.cityofwhiteplains.com The City of White Plains Programs WHITE PLAINS Office of the Mayor CITY OFFICIALS City of White Plains, Office of the Mayor 255 Main Street, White Plains NY 10601 Mayor Thomas M. Roach Dear Fellow Resident: Council President I am pleased to present the 2019 Spring/Summer City Guide. The John Martin Guide is a resource for the season, detailing information on the City’s twenty multi-purpose parks, programming for all ages and Common Council abilities, special events and community partnerships. Justin Brasch “Spring’s greatest joy beyond a doubt, is when it brings the John Kirkpatrick children out.” – Edgar Guest With the return of warmer Dennis Krolian temperatures and longer days, I hope to see you around town enjoying some of the upcoming Milagros Lecuona events: Nadine Hunt-Robinson * Saturday, March 9th, the 22nd Annual White Plains St. Patrick’s Day Parade, Mamaroneck Avenue, John Martin * Tuesday, March 26th, White Plains Harlem Fine Arts Show, 360 Hamilton Avenue, Recreation * Saturday, April 20th, the Funny Bunny Morning, White Plains Performing Arts Center, Advisory * Wednesday, April 24th, Farmers’ Market, Court Street Committee * Saturday, April 27th, White Plains Comic Fest, White Plains Galleria, Nadine Hunt-Robinson * Sunday, April 28th, the Annual Cherry Blossom Festival, Turnure Park, Chairperson * Saturday, May 11th, Youth Bureau STEAM Fair, Eastview Middle -

WHITE PLAINS HIGH SCHOOL 2019 Class Profile

WHITE PLAINS HIGH SCHOOL 2019 Class Profile White Plains High School Ellen Doherty CEEB Code: 335955 550 North Street Principal White Plains, NY 10605 (914) 422-2182 ♦ Fax: (914) 422-2196 www.whiteplainspublicschools.org Mission Statement Sara Hall Assistant Principal, Guidance Services The mission of the White (914) 422-3675 [email protected] Plains City School District is to educate and inspire Counseling Staff all students, while Rob Baddeley (914) 422-2424 [email protected] nurturing their dreams, so Enrique Cafaro (914) 422-2149 [email protected] they learn continually, Maria Csikortos (914) 422-2148 [email protected] think critically, pursue Karen Day (914) 422-2167 [email protected] their aspirations and Lily Diaz-Withers (914) 422-2147 [email protected] contribute to a diverse and Erin Harrison (914) 422-2150 [email protected] dynamic world. Jeffrey Hirsch (914) 422-2232 [email protected] Genevieve Little (914) 422-2427 [email protected] Magda Martas (914) 422-2175 [email protected] Marcos Monteagudo (914) 422-2168 [email protected] Alvera Pollard (914) 422-2164 [email protected] Denise Velasquez (914) 422-2163 [email protected] National High School of Excellence White Plains is a thriving suburban city with an economically and racially diverse population of close to 50,000 and is located about 25 miles northeast of New York City. White Plains High School offers unique educational opportunities, highly qualified staff, and extensive facilities, and is located on a beautiful 75-acre campus. -

LHVA 17 Travel 2019-2020: Player and Parent Contact

LHVA 17 Travel 2019-2020: Player and Parent Contact First Last City School Parent 1 First Parent 1 Last Parent 1 Email Parent 2 First Parent 2 Last Parent 2 Email Elissa Berger Larchmont Mamaroneck High School Marcie Berger [email protected] Mark Berger Alyssa Bucci Rye Brook Blind Brook HIgh School John Bucci [email protected] Lisa Bucci [email protected] Natalia Cherner TUCKAHOE Pelham HS D CERNER [email protected] Kayla Cruz Larchmont Mamaroneck high school Robert Cruz [email protected] Kim Cruz [email protected] Shannon Holland Pelham Pelham Memorial High School Kimberly Zirolnik [email protected] Scott Holland [email protected] Mariana Julian Rye Brook Blind Brook High Schhol Wilson Julian [email protected] Sandra Julian [email protected] Sophia Lotto Eastchester Eastchester HS Adele Lotto [email protected] Mia Murrell Scarsdale Eastchester hallie rifkin [email protected] john bagley [email protected] Mila Panchich Pelham Manor Pelham HS Margie Chiu [email protected] Emilia Pantigoso Larchmont Mamaroneck High School Jane King [email protected] Joe Pantigoso Julia Rogovic Rye Brook Blind Brook High School Jill Rogovic [email protected] Andy Rogovic [email protected] Adrianna Sherwood Port Chester Port Chester High School Blanca Lopez [email protected] James Sherwood [email protected] Sophia Silvera New Rochelle New Rochelle HS Jhovanna Silvera [email protected] Mario Silvera [email protected] Solee West White Plains White Plains High School NADIA SMITH [email protected] Cary Smith [email protected].