PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT Project Insights Assessment of the National Innovation System of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Mace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

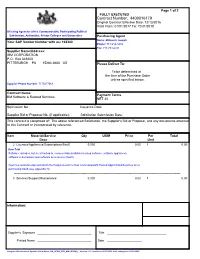

Contract Number: 4400016179

Page 1 of 2 FULLY EXECUTED Contract Number: 4400016179 Original Contract Effective Date: 12/13/2016 Valid From: 01/01/2017 To: 12/31/2018 All using Agencies of the Commonwealth, Participating Political Subdivision, Authorities, Private Colleges and Universities Purchasing Agent Name: Millovich Joseph Your SAP Vendor Number with us: 102380 Phone: 717-214-3434 Fax: 717-783-6241 Supplier Name/Address: IBM CORPORATION P.O. Box 643600 PITTSBURGH PA 15264-3600 US Please Deliver To: To be determined at the time of the Purchase Order unless specified below. Supplier Phone Number: 7175477069 Contract Name: Payment Terms IBM Software & Related Services NET 30 Solicitation No.: Issuance Date: Supplier Bid or Proposal No. (if applicable): Solicitation Submission Date: This contract is comprised of: The above referenced Solicitation, the Supplier's Bid or Proposal, and any documents attached to this Contract or incorporated by reference. Item Material/Service Qty UOM Price Per Total Desc Unit 2 Licenses/Appliances/Subscriptions/SaaS 0.000 0.00 1 0.00 Item Text Software: includes, but is not limited to, commercially available licensed software, software appliances, software subscriptions and software as a service (SaaS). Agencies must develop and attach the Requirements for Non-Commonwealth Hosted Applications/Services when purchasing SaaS (see Appendix H). -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Services/Support/Maintenance 0.000 0.00 -

Smart Networks and Services Version 30 June 2020

Draft proposal for a European Partnership under Horizon Europe Smart Networks and Services Version 30 June 2020 Summary The European communication networking and services sector is proposing the Smart Networks and Services Partnership to secure European leadership in the development and deployment of next generation network technologies and services, while accelerating European industry digitization. It will position Europe as a lead market and positively impact the citizens’ quality of life, while boosting the European data economy and contributing to ensure European sovereignty in critical supply chains. This document is supported by ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5G-IA and the Networld2020 European Technology Platform launched a Smart Networks and Services Task Force to prepare this Partnership proposal in Horizon Europe. AIOTI joined the Task Force. Additional contributors are from Cispe.cloud and the NESSI European Technology Platform. All these organizations appreciate the work of the Task Force and approved this report. DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This document contains material which is prepared by 5G-IA, the Networld2020 European Technology Platform, AIOTI, Cispe.cloud and the NESSI European Technology Platform and is based on referenced material and documents from public institutions and industry associations. 1 About this draft In autumn 2019 the Commission services asked potential partners to further elaborate proposals for the candidate European Partnerships identified during the strategic planning of Horizon Europe. These proposals have been developed by potential partners based on common guidance and template, taking into account the initial concepts developed by the Commission and feedback received from Member States during early consultation1. The Commission Services have guided revisions during drafting to facilitate alignment with the overall EU political ambition and compliance with the criteria for Partnerships. -

Draft Proposal for a European Partnership Under Horizon Europe European Partnership on Innovative Smes

Draft proposal for a European Partnership under Horizon Europe European Partnership on Innovative SMEs Version 25.05.20201 About this draft In autumn 2019 the Commission services asked potential partners to further elaborate proposals for the candidate European Partnerships identified during the strategic planning of Horizon Europe. These proposals have been developed by potential partners based on common guidance and template, taking into account the initial concepts developed by the Commission and feedback received from Member States during early consultation2. The Commission Services have guided revisions during drafting to facilitate alignment with the overall EU political ambition and compliance with the criteria for Partnerships. This document is a stable draft of the partnership proposal, released for the purpose of ensuring transparency of information on the current status of preparation (including on the process for developing the Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda). As such, it aims to contribute to further collaboration, synergies and alignment between partnership candidates, as well as more broadly with related R&I stakeholders in the EU, and beyond where relevant. This informal document does not reflect the final views of the Commission, nor pre-empt the formal decision-making (comitology or legislative procedure) on the establishment of European Partnerships. In the next steps of preparations, the Commission Services will further assess these proposals against the selection criteria for European Partnerships. The final decision on launching a Partnership will depend on progress in their preparation (incl. compliance with selection criteria) and the formal decisions on European Partnerships (linked with the adoption of Strategic Plan, work programmes, and legislative procedures, depending on the form). -

History of Eureka

1954 2020 U R E K A E HISTORY BI5 OF EUREKA SINCE 1954 Year Event notice: 1954 Establishment EUREKA, Brussels published „Moniteur belge“ N. 415 page 180 Inauguration of „Tantae Molis Erat“ - Knights of Belge as „Le Merite de l'invention; both on 22. January, 1954 60s around 300 inventions and 250 Innovators in average. 70s around 500 inventions and 300 Innovators in average at „Martini Building“ 1973 Exhibitions in Brussels President Eureka: Prof. José Loriaux New Logo: 80s around 1.100 inventions and 750 Innovators in average; still at Mar- tini Building. 1 1985 Initiative of France and Germany to build up Eureka funds. 90s together with EU Commission International Jury with: XXII together with „Organisation R.F. Mikhail Gorodissky PhD, Lawyer Sergey Dudush- Mondiale de la Presse Periodique“ kin, Partner „Gorodissky & Partner“China, President together with European Patent Zhank, China Science Ressources Austria, Senator Office Prof. Otto F. Joklik Belgium, George Asselberghs 1992 together with „Chambre Belge des Inventeurs“ and „Ministry of Eco- nomy“, Belgium Patronage King of Spain S.M. Juan Carlos I … as Grand Cross Officer „TME“ 1997 First time in „Les Pyramides“ Prof. Pierre Fumiere, President Int.Jury H.E. Guy Cudell Place the Rogier 2, 1210 Bruxelles Grandmaster of the Order T.M.E. previous Mayor of Participation of „RPS Innovative Brussels. Investment Banking“ Participation of „Russian Ministry of Defence“ 1998 Patronage of Kingdom of Morocco S.M. King Hassan II...as Grand Cross Officer T.M.E. 2 1999 Patronage of Kingdom of Belgium, HRH Prince Laurent as Grand Cross Officer T.M.E. -

Irish in Australia

THE IRISH IN AUSTRALIA. BY THE SAME AUTHOR. AN AUSTRALIAN CHRISTMAS COLLECTIONt A Series of Colonial Stories, Sketches , and Literary Essays. 203 pages , handsomely bound in green and gold. Price Five Shillings. A VERYpleasant and entertaining book has reached us from Melbourne. The- author, Mr. J. F. Hogan, is a young Irish-Australian , who, if we are to judge- from the captivating style of the present work, has a brilliant future before him. Mr. Hogan is well known in the literary and Catholic circles of the Australian Colonies, and we sincerely trust that the volume before us will have the effect of making him known to the Irish people at home and in America . Under the title of " An Australian Christmas Collection ," Mr. Hogan has republished a series of fugitive writings which he had previously contributed to Australian periodicals, and which have won for the author a high place in the literary world of the. Southern hemisphere . Some of the papers deal with Irish and Catholic subjects. They are written in a racy and elegant style, and contain an amount of highly nteresting matter relative to our co-religionists and fellow -countrymen under the Southern Cross. A few papers deal with inter -Colonial politics , and we think that home readers will find these even more entertaining than those which deal more. immediately with the Irish element. We have quoted sufficiently from this charming book to show its merits. Our readers will soon bear of Mr. Hogan again , for he has in preparation a work on the "Irish in Australia," which, we are confident , will prove very interesting to the Irish people in every land. -

Rules and Regulations Eureka Series 2021

EUREKA SERIES 2021 Edition Edited on 22 April 2021 RULES & REGULATIONS 1. Introduction EUREKA SERIES – hereby referred to as “the programme” or “the training programme” – is a training programme initiated and organised by SERIES MANIA (Association du Festival international des séries de Lille / Hauts-de-France) in partnership with LA FEMIS (Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Métiers de l’Image et du Son). EUREKA SERIES is one of the training programmes carried out by the SERIES MANIA INSTITUTE. The SERIES MANIA INSTITUTE is an initiative created by SERIES MANIA to reinforce the training of European professionals working in the television sector, with three main objectives: - Create a European creative network to encourage the sharing of knowledge and creative emulation across borders - Remove barriers between television professions, to unite writers, directors, producers and broadcasters around a common work culture, in order to improve the flow of the creative process and respond to an increase in production volume - Open up the industry to more diverse profiles, allowing more representation in the stories that are told and in who is telling them. EUREKA SERIES is a 14-week full-time training programme targeting television drama series writers and producers from all over Europe. EUREKA SERIES takes place in Lille, in the Hauts-de-France region. Through lectures, masterclasses, case studies and practical workshops on transnational series, its aim is to strengthen the common language between European series writers and producers and increase their knowledge of the great diversity of production ecosystems on the continent, from a financial, regulatory and cultural perspective. This will facilitate future cross-border collaborations and inspire them to transform their local working methods. -

Digital Terrestrial Radio for Australia

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament RESEARCH PAPER www.aph.gov.au/library 19 December, no. 18, 2008–09, ISSN 1834-9854 Going digital—digital terrestrial radio for Australia Dr Rhonda Jolly Social Policy Section Executive summary th • Since the early 20 century radio has been an important source of information and entertainment for people of various ages and backgrounds. • Almost every Australian home and car has at least one radio and most Australians listen to radio regularly. • The introduction of new radio technology—digital terrestrial radio—which can deliver a better listening experience for audiences, therefore has the potential to influence people’s lives significantly. • Digital radio in a variety of technological formats has been established in a number of countries for some years, but it is expected only to become a reality in Australia sometime in 2009. • Unlike the idea of digital television however, digital radio has not fully captured the imagination of audiences and in some markets there are suggestions that it is no longer relevant. • This paper provides a simple explanation of the major digital radio standards and a brief history of their development. It particularly examines the standard chosen for Australia, the Eureka 147 standard (known also as Digital Audio Broadcasting or DAB). • The paper also traces the development of digital radio policy in Australia and considers issues which may affect the future of the technology. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Radio basics: AM and FM radio ................................................................................................. 3 How do AM and FM work? ................................................................................................... 3 How AM radio works ....................................................................................................... -

Digitally Empowered Generation Equality EUROPE Women, Girls and ICT in the Context of COVID-19 in Selected Western Balkan and Eastern Partnership Countries

ITUPublications International Telecommunication Union Europe 2021 Digitally empowered Generation Equality EUROPE Women, girls and ICT in the context of COVID-19 in selected Western Balkan and Eastern Partnership countries In partnership with: Digitally empowered Generation Equality Generation Digitally empowered Digitally empowered Generation Equality: Women, girls and ICT in the context of COVID-19 in selected Western Balkan and Eastern Partnership countries DISCLAIMER The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ITU concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ITU in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by ITU to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. The opinions, findings and conclusions expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of ITU or its membership. Please consider the environment before printing this report. © ITU 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is licensed to the public through a Creative Commons Attribution-Non- Commercial-Share Alike 3.0 IGO license (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO). -

Tracker Master 9.25.18 TM

IT Services & BPO Implied Implied Implied Announce Target Target Description Buyer Enterprise EV/ EV/ Transaction Comments Date Value ($M) Revenue EBITDA Calligo (UK) Ltd acquired Network Integrity Services Ltd for an undisclosed amount. The acquisition Network Integrity {match score: 00} Network Integrity Services provides an array of services, including IT consulting, web would allow Calligo (UK) Ltd to expand its local presence throughout the United Kingdom. Network 12/3/2020 Calligo (UK) Ltd. NA NA NA Services Ltd. design, and systems integration. Integrity Services Ltd is located in Salford, Greater Manchester, United Kingdom and provides information technology services. It has around 160 employees. {match score: 00} BigBear, Inc. provides cost effective and cutting edge information technology NuWave Solutions LLC acquired Big Open Inc, trading as BigBear Inc for an undisclosed amount. The NuWave 12/3/2020 BigBear, Inc. solutions. It offers software design, engineering, and platform development services to its customers. NA NA NA transaction would enhance NuWave Solutions LLC’s existing capabilities. Founded in 2008, Big Open Solutions LLC The company was founded in 2008 and is headquartered in San Diego, CA. Inc is located in San Diego, California, United States and provides software services. {match score: 00} In 2002, four friends saw the need for true customer service in the Ottawa IT and computer industry, so they took action. Mathew Lafrance, Christian Ste-Marie, Allan Ghosn and Mathieu Bouchard joined forces to bring their idea to life and excellent IT services to market. There Convergence Networks acquired Grade A for an undisclosed amount. The acquisition is in line with the was no shortage of companies selling hardware and software, but after-sales IT support was (and still Convergence growth strategy of both the companies and enhances their service offerings. -

Background Report Horizon 2020 Policy Support Facility

Specific support to Bulgaria - Background report Horizon 2020 Policy Support Facility EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Research & Innovation Directorate A — Policy Development and Coordination Unit A4— Analysis and monitoring of national research and innovation policies Contact (H2020 PSF Specific Support to Latvia): Román ARJONA, Chief Economist and Head of Unit A4 - [email protected] Diana IVANOVA-VAN BEERS, Policy Officer - [email protected] Contact (H2020 PSF coordination team): Román ARJONA, Chief Economist and Head of Unit A4 - [email protected] Stéphane Vankalck, Head of Sector PSF - Sté[email protected] Diana Senczyszyn, Team leader Policy Support - [email protected] [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels EUROPEAN COMMISSION Specific support to Bulgaria - Background report Horizon 2020 Policy Support Facility Written by: Ruslan Zhechkov and Bea Mahieu Technopolis Group 2017 Directorate-General for Research and Innovation EN EUROPE DIRECT is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you) LEGAL NOTICE This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017. PDF ISBN 978-92-79-73424-3 doi:10.2777/976598 KI-AX-17-012-EN-N © European Union, 2017. -

The Eureka Network

The Eureka Network Full members 41 full members (40 countries + European Commission) Partner countries (South Korea) Associated countries (Argentina, Canada, Chile, South Africa) National information points (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina) International cooperation We are the world’s biggest public network for international cooperation in R&D and innovation, present in over 45 countries. An overview Eureka offers International New business High degree Freedom to Strong bottom-up co-operations opportunities of flexibility create consortia approach 70%+ 60%+ 1985 2019 42.6+ billion € 7100+ projects public-private funding launched invested 14900+ 4700+ 4800+ 8800+ SMEs Universities Research Large Centres Companies 5 Participants in Eureka projects Large Companies 63% SMEs 59% SMEs Research Institutes Universities Others 45% 42% 24% 23% 17% Large Companies 16% 16% Universities 13% 13% 13% 13% 12% 11% 10% Research Institutes Others 5% 3% 1% 1% 1985-1994 1995-2004 2005-2014 2015-TODAY 6 Electronics, IT and Telecoms Technology 28% Top 5 Biological Sciences / Technologies Technological Areas 28% Industrial Manufacturing, Material and Transport 18% Energy Technology 7% Data for EUREKA Projects and Eurostars Technology for Protecting Man and the Environment 5% 7 Medical / Health Related 32% Industrial Products / Manufacturing 17% Top 5 Computer Related Market Areas 8% Energy 7% Transportation Data for EUREKA Projects and Eurostars 6% 8 We help our participants to succeed Close to market Significant increase in annual turnover of EUREKA Eureka participating -

EUROSTARS Funding Excellence in Innovation

Aim Higher EUROSTARS Funding excellence in innovation Guidelines for evaluating the applications September 2014 Version 1.1 Aim Higher This document provides experts with a description of the evaluation criteria and how to apply them to a Eurostars application. © EUREKA Secretariat, 2014 No part of this document may be reproduced in whole or in part without the express written consent of the EUREKA Secretariat. Publication date: September 2014 Version 1.1 Eureka Association - B - 1040 BRUSSELS Eurostars is a joint programme between more than T +32 2 777 09 50 30 EUREKA member countries and the European Union www.eurostars-eureka.eu CONTACT > www.eurostars-eureka.eu/#in-your-country Aim Higher CONTENTS Important things to know 4 Eurostars uses a two-step expert evaluation process 4 What the experts do 4 Experts have the ability to exclude poor quality applications 4 Your output must be useful and relevant 4 We expect assessments of excellent quality 5 We expect you to follow our code of practice 5 We take conflict of interest seriously 5 Evaluation documents 7 Documents relating to the application 7 Documents you need to perform the evaluation 7 Glossary 7 To do list 8 Explanations 9 Section 1 – The three main criteria and their sub criteria 9 Quality and efficiency of the implementation – Project planning and consortium quality 9 Impact 11 Excellence 13 Section 2 - Summary 15 Section 3 - Final questions 15 How Eurostars selects, assigns and works with experts 16 Availability 16 Selection 16 Assignment 16 Performing the work 17 Delivery 17 Confidentiality 18 The EUREKA Secretariat 18 The Expert 19 Information Security 19 Electronic submission of application documents 19 Data Protection Act 19 Guidelines for evaluating Eurostars is a joint programme between more than the applications 30 EUREKA member countries and the European Union Aim Higher Important things to know Eurostars uses a two-step expert evaluation process An application must navigate through a number of different steps if it is to become approved and receive financial support.