A New Framework of Analysis for the First Anglo-Afghan War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pashtunistan: Pakistan's Shifting Strategy

AFGHANISTAN PAKISTAN PASHTUN ETHNIC GROUP PASHTUNISTAN: P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER May 2012 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? P ASHTUNISTAN : P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER About Tribal Analysis Center Tribal Analysis Center, 6610-M Mooretown Road, Box 159. Williamsburg, VA, 23188 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? The Pashtun tribes have yearned for a “tribal homeland” in a manner much like the Kurds in Iraq, Turkey, and Iran. And as in those coun- tries, the creation of a new national entity would have a destabilizing impact on the countries from which territory would be drawn. In the case of Pashtunistan, the previous Afghan governments have used this desire for a national homeland as a political instrument against Pakistan. Here again, a border drawn by colonial authorities – the Durand Line – divided the world’s largest tribe, the Pashtuns, into two the complexity of separate nation-states, Afghanistan and Pakistan, where they compete with other ethnic groups for primacy. Afghanistan’s governments have not recog- nized the incorporation of many Pashtun areas into Pakistan, particularly Waziristan, and only Pakistan originally stood to lose territory through the creation of the new entity, Pashtunistan. This is the foundation of Pakistan’s policies toward Afghanistan and the reason Pakistan’s politicians and PASHTUNISTAN military developed a strategy intended to split the Pashtuns into opposing groups and have maintained this approach to the Pashtunistan problem for decades. Pakistan’s Pashtuns may be attempting to maneuver the whole country in an entirely new direction and in the process gain primacy within the country’s most powerful constituency, the military. -

Resettlement Policy Framework

Khyber Pass Economic Corridor (KPEC) Project (Component II- Economic Corridor Development) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Resettlement Policy Framework Public Disclosure Authorized Peshawar Public Disclosure Authorized March 2020 RPF for Khyber Pass Economic Corridor Project (Component II) List of Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank AH Affected household AI Access to Information APA Assistant Political Agent ARAP Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan BHU Basic Health Unit BIZ Bara Industrial Zone C&W Communication and Works (Department) CAREC Central Asian Regional Economic Cooperation CAS Compulsory acquisition surcharge CBN Cost of Basic Needs CBO Community based organization CETP Combined Effluent Treatment Plant CoI Corridor of Influence CPEC China Pakistan Economic Corridor CR Complaint register DPD Deputy Project Director EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA Environmental Protection Agency ERRP Emergency Road Recovery Project ERRRP Emergency Rural Road Recovery Project ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FBR Federal Bureau of Revenue FCR Frontier Crimes Regulations FDA FATA Development Authority FIDIC International Federation of Consulting Engineers FUCP FATA Urban Centers Project FR Frontier Region GeoLoMaP Geo-Referenced Local Master Plan GoKP Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa GM General Manager GoP Government of Pakistan GRC Grievances Redressal Committee GRM Grievances Redressal Mechanism IDP Internally displaced people IMA Independent Monitoring Agency -

The Causes of the First Anglo-Afghan War

wbhr 1|2012 The Causes of the First Anglo-Afghan War JIŘÍ KÁRNÍK Afghanistan is a beautiful, but savage and hostile country. There are no resources, no huge market for selling goods and the inhabitants are poor. So the obvious question is: Why did this country become a tar- get of aggression of the biggest powers in the world? I would like to an- swer this question at least in the first case, when Great Britain invaded Afghanistan in 1839. This year is important; it started the line of con- flicts, which affected Afghanistan in the 19th and 20th century and as we can see now, American soldiers are still in Afghanistan, the conflicts have not yet ended. The history of Afghanistan as an independent country starts in the middle of the 18th century. The first and for a long time the last man, who united the biggest centres of power in Afghanistan (Kandahar, Herat and Kabul) was the commander of Afghan cavalrymen in the Persian Army, Ahmad Shah Durrani. He took advantage of the struggle of suc- cession after the death of Nāder Shāh Afshār, and until 1750, he ruled over all of Afghanistan.1 His power depended on the money he could give to not so loyal chieftains of many Afghan tribes, which he gained through aggression toward India and Persia. After his death, the power of the house of Durrani started to decrease. His heirs were not able to keep the power without raids into other countries. In addition the ruler usually had wives from all of the important tribes, so after the death of the Shah, there were always bloody fights of succession. -

Arta 2005.001

ARTA 2005.001 St John Simpson - The British Museum Making their mark: Foreign travellers at Persepolis The ruins at Persepolis continue to fascinate scholars not least through the perspective of the early European travellers’ accounts. Despite being the subject of considerable study, much still remains to be discovered about this early phase of the history of archaeology in Iran. The early published literature has not yet been exhausted; manuscripts, letters, drawings and sculptures continue to emerge from European collections, and a steady trickle of further discoveries can be predicted. One particularly rich avenue lies in further research into the personal histories of individuals who are known to have been resident in or travelling through Iran, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries. These sources have value not only in what may pertain to the sites or antiquities, but they also add useful insights into the political and socio-economic situation within Iran during this period (Wright 1998; 1999; Simpson in press; forthcoming). The following paper offers some research possibilities by focusing on the evidence of the Achemenet janvier 2005 1 ARTA 2005.001 Fig. 1: Gate of All Nations graffiti left by some of these travellers to the site. Some bio- graphical details have been added where considered appro- priate but many of these individuals deserve a level of detailed research lying beyond the scope of this preliminary survey. Achemenet janvier 2005 2 ARTA 2005.001 The graffiti have attracted the attention of many visitors to the site, partly because of their visibility on the first major building to greet visitors to the site (Fig. -

Kandahar Survey Report

Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan I AREA Kandahar Survey Report February 1996 AREA Office 17 - E Abdara Road UfTow Peshawar, Pakistan Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan I AREA Kandahar Survey Report Prepared by Eng. Yama and Eng. S. Lutfullah Sayed ·• _ ....... "' Content - Introduction ................................. 1 General information on Kandahar: - Summery ........................... 2 - History ........................... 3 - Political situation ............... 5 - Economic .......................... 5 - Population ........................ 6 · - Shelter ..................................... 7 -Cost of labor and construction material ..... 13 -Construction of school buildings ............ 14 -Construction of clinic buildings ............ 20 - Miscellaneous: - SWABAC ............................ 2 4 -Cost of food stuff ................. 24 - House rent· ........................ 2 5 - Travel to Kanadahar ............... 25 Technical recommendation .~ ................. ; .. 26 Introduction: Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan/ AREA intends to undertake some rehabilitation activities in the Kandahar province. In order to properly formulate the project proposals which AREA intends to submit to EC for funding consideration, a general survey of the province has been conducted at the end of Feb. 1996. In line with this objective, two senior staff members of AREA traveled to Kandahar and collect the required information on various aspects of the province. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

Geopolitics of Afghanistan Course No: SA653 Total Credits: 3 (Three) Course Teacher: Dr

Course Title: Geopolitics of Afghanistan Course No: SA653 Total Credits: 3 (Three) Course Teacher: Dr. Ambrish Dhaka INTRODUCTION This course is designed to impart understanding of geopolitics of Afghanistan. The location of Afghanistan has been a source to every U-turn in Afghanistan’s national life. It always had extraneous factors deeply embedded into ethno-political strife taking aback decade’s progress into one backwash. The geographical setting of Afghanistan has had important bearing on its autochthonous ethno-national life that needs be studied under ethnicity and its internal hierarchy. The Imperial period and the Cold War geopolitics had been reckoning example of Afghanistan’s location in World Order. Based on above facets of Afghanistan, an understanding of the region’s geopolitical dynamics can be carved out for the present century with in the most current context. INSTRUCTION METHOD: Lectures, Web-Digital content, Seminars/Tutorials EVALUATION PATTERN: Sessional Work and Semester Examination COURSE CONTENTS 1. Geographical Setting of Afghanistan: location & political frontiers, physiography, climate, natural resources & land use. 2. Afghanistan’s Geopolitical Epochs: Anglo-Afghan Wars & the Concept of Great Game, the Cold War resistance and the post-Cold War Geopolitics. 3. Geopolitical Matrix: Regional players- Iran, Pakistan, China and Central Asia, Global players- Russia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and the US. 4. Geoeconomic evaluation: Oil geoeconomics; Economic-strategic location of Afghanistan vis-à-vis South Asia and Central Asia; Reinventing the Silk Route - the TAGP & TARR routes. 5. India- the extended neighbourhood, Af-Pak and the South Asian regional geopolitics. SELECTED READINGS Amin, Tahir. Afghanistan Crises Implications for Muslim World, Iran and Pakistan, Washington, 1982. -

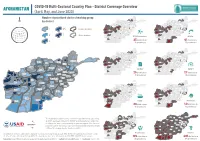

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

The Informal Regulation of the Onion Market in Nangarhar, Afghanistan Working Paper 26 Giulia Minoia, Wamiqullah Mumatz and Adam Pain November 2014 About Us

Researching livelihoods and Afghanistan services affected by conflict Kabul Jalalabad The social life of the Nangarhar Pakistan onion: the informal regulation of the onion market in Nangarhar, Afghanistan Working Paper 26 Giulia Minoia, Wamiqullah Mumatz and Adam Pain November 2014 About us Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) aims to generate a stronger evidence base on how people make a living, educate their children, deal with illness and access other basic services in conflict-affected situations. Providing better access to basic services, social protection and support to livelihoods matters for the human welfare of people affected by conflict, the achievement of development targets such as the Millennium Development Goals and international efforts at peace- building and state-building. At the centre of SLRC’s research are three core themes, developed over the course of an intensive one- year inception phase: . State legitimacy: experiences, perceptions and expectations of the state and local governance in conflict-affected situations . State capacity: building effective states that deliver services and social protection in conflict- affected situations . Livelihood trajectories and economic activity under conflict The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) is the lead organisation. SLRC partners include the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) in Sri Lanka, Feinstein International Center (FIC, Tufts University), Focus1000 in Sierra Leone, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), -

Afghanistan: Political Exiles in Search of a State

Journal of Political Science Volume 18 Number 1 Article 11 November 1990 Afghanistan: Political Exiles In Search Of A State Barnett R. Rubin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Rubin, Barnett R. (1990) "Afghanistan: Political Exiles In Search Of A State," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 18 : No. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol18/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ,t\fghanistan: Political Exiles in Search of a State Barnett R. Ru bin United States Institute of Peace When Afghan exiles in Pakistan convened a shura (coun cil) in Islamabad to choose an interim government on February 10. 1989. they were only the most recent of exiles who have aspired and often managed to Mrule" Afghanistan. The seven parties of the Islamic Union ofM ujahidin of Afghanistan who had convened the shura claimed that. because of their links to the mujahidin fighting inside Afghanistan. the cabinet they named was an Minterim government" rather than a Mgovernment-in exile. ~ but they soon confronted the typical problems of the latter: how to obtain foreign recognition, how to depose the sitting government they did not recognize, and how to replace the existing opposition mechanisms inside and outside the country. Exiles in Afghan History The importance of exiles in the history of Afghanistan derives largely from the difficulty of state formation in its sparsely settled and largely barren territory. -

Nation Building Process in Afghanistan Ziaulhaq Rashidi1, Dr

Saudi Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: Saudi J Humanities Soc Sci ISSN 2415-6256 (Print) | ISSN 2415-6248 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: http://scholarsmepub.com/sjhss/ Original Research Article Nation Building Process in Afghanistan Ziaulhaq Rashidi1, Dr. Gülay Uğur Göksel2 1M.A Student of Political Science and International Relations Program 2Assistant Professor, Istanbul Aydin University, Istanbul, Turkey *Corresponding author: Ziaulhaq Rashidi | Received: 04.04.2019 | Accepted: 13.04.2019 | Published: 30.04.2019 DOI:10.21276/sjhss.2019.4.4.9 Abstract In recent times, a number of countries faced major cracks and divisions (religious, ethnical and geographical) with less than a decade war/instability but with regards to over four decades of wars and instabilities, the united and indivisible Afghanistan face researchers and social scientists with valid questions that what is the reason behind this unity and where to seek the roots of Afghan national unity, despite some minor problems and ethnic cracks cannot be ignored?. Most of the available studies on nation building process or Afghan nationalism have covered the nation building efforts from early 20th century and very limited works are available (mostly local narratives) had touched upon the nation building efforts prior to the 20th. This study goes beyond and examine major struggles aimed nation building along with the modernization of state in Afghanistan starting from late 19th century. Reforms predominantly the language (Afghani/Pashtu) and role of shared medium of communication will be deliberated. In addition, we will talk how the formation of strong centralized government empowered the state to initiate social harmony though the demographic and geographic oriented (north-south) resettlement programs in 1880s and how does it contributed to the nation building process. -

Beyond 'Tribal Breakout': Afghans in the History of Empire, Ca. 1747–1818

Beyond 'Tribal Breakout': Afghans in the History of Empire, ca. 1747–1818 Jagjeet Lally Journal of World History, Volume 29, Number 3, September 2018, pp. 369-397 (Article) Published by University of Hawai'i Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jwh.2018.0035 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/719505 Access provided at 21 Jun 2019 10:40 GMT from University College London (UCL) Beyond ‘Tribal Breakout’: Afghans in the History of Empire, ca. 1747–1818 JAGJEET LALLY University College London N the desiccated and mountainous borderlands between Iran and India, Ithe uprising of the Hotaki (Ghilzai) tribes against Safavid rule in Qandahar in 1717 set in motion a chain reaction that had profound consequences for life across western, south, and even east Asia. Having toppled and terminated de facto Safavid rule in 1722,Hotakiruleatthe centre itself collapsed in 1729.1 Nadir Shah of the Afshar tribe—which was formerly incorporated within the Safavid political coalition—then seized the reigns of the state, subduing the last vestiges of Hotaki power at the frontier in 1738, playing the latter off against their major regional opponents, the Abdali tribes. From Kandahar, Nadir Shah and his new allies marched into Mughal India, ransacking its cities and their coffers in 1739, carrying treasure—including the peacock throne and the Koh-i- Noor diamond—worth tens of millions of rupees, and claiming de jure sovereignty over the swathe of territory from Iran to the Mughal domains. Following the execution of Nadir Shah in 1747, his former cavalry commander, Ahmad Shah Abdali, rapidly established his independent political authority.2 Adopting the sobriquet Durr-i-Durran (Pearl of 1 Rudi Matthee, Persia in Crisis.