The Procurement of Food by Public Sector Organisations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stewart2019.Pdf

Political Change and Scottish Nationalism in Dundee 1973-2012 Thomas A W Stewart PhD Thesis University of Edinburgh 2019 Abstract Prior to the 2014 independence referendum, the Scottish National Party’s strongest bastions of support were in rural areas. The sole exception was Dundee, where it has consistently enjoyed levels of support well ahead of the national average, first replacing the Conservatives as the city’s second party in the 1970s before overcoming Labour to become its leading force in the 2000s. Through this period it achieved Westminster representation between 1974 and 1987, and again since 2005, and had won both of its Scottish Parliamentary seats by 2007. This performance has been completely unmatched in any of the country’s other cities. Using a mixture of archival research, oral history interviews, the local press and memoires, this thesis seeks to explain the party’s record of success in Dundee. It will assess the extent to which the character of the city itself, its economy, demography, geography, history, and local media landscape, made Dundee especially prone to Nationalist politics. It will then address the more fundamental importance of the interaction of local political forces that were independent of the city’s nature through an examination of the ability of party machines, key individuals and political strategies to shape the city’s electoral landscape. The local SNP and its main rival throughout the period, the Labour Party, will be analysed in particular detail. The thesis will also take time to delve into the histories of the Conservatives, Liberals and Radical Left within the city and their influence on the fortunes of the SNP. -

2021 MSP Spreadsheet

Constituency MSP Name Party Email Airdrie and Shotts Neil Gray SNP [email protected] Coatbridge and Chryston Fulton MacGregor SNP [email protected] Cumbernauld and Kilsyth Jamie Hepburn SNP [email protected] East Kilbride Collette Stevenson SNP [email protected] Falkirk East Michelle Thomson SNP [email protected] Falkirk West Michael Matheson SNP [email protected] Hamilton, Larkhall and Stonehouse Christina McKelvie SNP [email protected] Motherwell and Wishaw Clare Adamson SNP [email protected] Uddingston and Bellshill Stephanie Callaghan SNP [email protected] Regional Central Scotland Richard Leonard Labour [email protected] Central Scotland Monica Lennon Labour [email protected] Central Scotland Mark Griffin Labour [email protected] Central Scotland Stephen Kerr Conservative [email protected] Central Scotland Graham Simpson Conservative [email protected] Central Scotland Meghan Gallacher Conservative [email protected] Central Scotland Gillian Mackay Green [email protected] Constituency MSP Name Party Email Glasgow Anniesland Bill Kidd SNP [email protected] Glasgow Cathcart James Dornan SNP [email protected] Glasgow Kelvin Kaukab Stewart SNP [email protected] Glasgow Maryhill and Springburn Bob Doris SNP [email protected] -

Scottish Parliament Photographs of Msps

Photographs of MSPs Dealbhan de na BPA May 2021 Each person in Scotland is represented by 8 Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs); 1 constituency MSP and 7 regional MSPs. A region is a larger area which covers a number of constituencies. Scottish National Party Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Scottish Labour Party Scottish Green Party Scottish Liberal Democrats No party affiliation C R Constituency Member Regional Member Contents MSP Photographs 2 Index of MSPs by Party 13 Index of MSPs by Constituency 15 Index of MSPs by Region 18 1 George Claire Adam Baker Paisley Mid Scotland and Fife C R Karen Jeremy Adam Balfour Banffshire and Lothian Buchan Coast C R Clare Colin Adamson Beattie Motherwell and Midlothian North Wishaw and Musselburgh C C Alasdair Neil Allan Bibby Na h-Eileanan West Scotland an Iar C R Tom Sarah Arthur Boyack Renfrewshire Lothian South C R Jackie Miles Baillie Briggs Dumbarton Lothian C R 2 Keith Jackson Brown Carlaw Clackmannanshire Eastwood and Dunblane C C Siobhian Finlay Brown Carson Ayr Galloway and West Dumfries C C Ariane Maggie Burgess Chapman Highlands and North East Islands Scotland R R Alexander Foysol Burnett Choudhury Aberdeenshire Lothian West C R Stephanie Katy Callaghan Clark Uddingston and West Bellshill Scotland C R Donald Willie Cameron Coffey Highlands and Kilmarnock and Islands Irvine Valley R C 3 Alex James Cole-Hamilton Dornan Edinburgh Glasgow Cathcart Western C C Angela Sharon Constance Dowey Almond Valley South Scotland C R Ash Jackie Denham Dunbar Edinburgh Aberdeen Eastern Donside -

Official Reporter, It Is a Homecoming of Sorts

Meeting of the Parliament (Hybrid) Tuesday 15 June 2021 Session 6 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.parliament.scot or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Tuesday 15 June 2021 CONTENTS Col. TIME FOR REFLECTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 POINT OF ORDER ............................................................................................................................................... 3 TOPICAL QUESTION TIME ................................................................................................................................... 4 Automated External Defibrillators (Amateur Sports Grounds) ..................................................................... 4 Racism in Schools ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Ferguson Marine Engineering Ltd ................................................................................................................ 8 COVID-19 ........................................................................................................................................................ 12 Statement—[First Minister]. The First Minister (Nicola Sturgeon) .......................................................................................................... -

Separatism and Regionalism in Modern Europe

Separatism and Regionalism in Modern Europe Separatism and Regionalism in Modern Europe Edited by Chris Kostov Logos Verlag Berlin λογος Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de . Book cover art: c Adobe Stock: Silvio c Copyright Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH 2020 All rights reserved. ISBN 978-3-8325-5192-6 The electronic version of this book is freely available under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence, thanks to the support of Schiller University, Madrid. Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH Georg-Knorr-Str. 4, Gebäude 10 D-12681 Berlin - Germany Tel.: +49 (0)30 / 42 85 10 90 Fax: +49 (0)30 / 42 85 10 92 https://www.logos-verlag.com Contents Editor's introduction7 Authors' Bios 11 1 The EU's MLG system as a catalyst for separatism: A case study on the Albanian and Hungarian minority groups 15 YILMAZ KAPLAN 2 A rolling stone gathers no moss: Evolution and current trends of Basque nationalism 39 ONINTZA ODRIOZOLA,IKER IRAOLA AND JULEN ZABALO 3 Separatism in Catalonia: Legal, political, and linguistic aspects 73 CHRIS KOSTOV,FERNANDO DE VICENTE DE LA CASA AND MARÍA DOLORES ROMERO LESMES 4 Faroese nationalism: To be and not to be a sovereign state, that is the question 105 HANS ANDRIAS SØLVARÁ 5 Divided Belgium: Flemish nationalism and the rise of pro-separatist politics 133 CATHERINE XHARDEZ 6 Nunatta Qitornai: A party analysis of the rhetoric and future of Greenlandic separatism 157 ELLEN A. -

MANIFESTO 2021 ”A Bold and Ambitious Policy Programme to Kickstart and Drive Recovery.”

MANIFESTO 2021 ”A bold and ambitious policy programme to kickstart and drive recovery.” The last year has been the hardest most of us have far - love, compassion and solidarity - should continue to ever experienced. light our path. The Covid pandemic has robbed too many families All that has mattered to me - as your First Minister - has of loved ones, and thousands of people across been doing my level best, each and every day, to steer us Scotland have suffered severe and, in many cases, through the crisis. I know I have made mistakes along the long lasting illness. way - the unprecedented nature of the crisis made that inevitable - but I have also learned from those mistakes Families and friends have spent months apart. So many and I do my best to apply the lessons learned to the of life’s basic pleasures - spending time with those we decisions the government is still taking. love, socialising in cafes, bars and restaurants, going to the gym, visiting the shops or the cinema, even getting a For all these reasons, this election really does matter - haircut - have been taken from us. possibly more than any other in our lifetimes. Children have lost months of normal schooling and At this time of crisis, more than ever, the country needs a missed the company of their friends and classmates. steady and experienced hand at the wheel. Young adults have missed out on the rites of passage If I am re-elected as your First Minister, I promise that associated with their first years of freedom. -

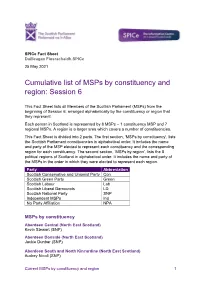

Cumulative List of Msps by Constituency and Region: Session 6

SPICe Fact Sheet Duilleagan Fiosrachaidh SPICe 25 May 2021 Cumulative list of MSPs by constituency and region: Session 6 This Fact Sheet lists all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) from the beginning of Session 6, arranged alphabetically by the constituency or region that they represent. Each person in Scotland is represented by 8 MSPs – 1 constituency MSP and 7 regional MSPs. A region is a larger area which covers a number of constituencies. This Fact Sheet is divided into 2 parts. The first section, ‘MSPs by constituency’, lists the Scottish Parliament constituencies in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSP elected to represent each constituency and the corresponding region for each constituency. The second section, ‘MSPs by region’, lists the 8 political regions of Scotland in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSPs in the order in which they were elected to represent each region. Party Abbreviation Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Con Scottish Green Party Green Scottish Labour Lab Scottish Liberal Democrats LD Scottish National Party SNP Independent MSPs Ind No Party Affiliation NPA MSPs by constituency Aberdeen Central (North East Scotland) Kevin Stewart (SNP) Aberdeen Donside (North East Scotland) Jackie Dunbar (SNP) Aberdeen South and North Kincardine (North East Scotland) Audrey Nicoll (SNP) Current MSPs by constituency and region 1 Aberdeenshire East (North East Scotland) Gillian Martin (SNP) Aberdeenshire West (North East Scotland) Alexander Burnett (Con) Airdrie -

Monday 5 July 2021 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean

Monday 5 July 2021 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean Change to membership of the Parliamentary Bureau The Presiding Officer wishes to inform Members that Gillian Mackay has replaced Patrick Harvie as the representative for the Scottish Green Party on the Parliamentary Bureau. Today's Business Meeting of the Parliament Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. There are no meetings today. Monday 5 July 2021 1 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Meeting of the Parliament There are no meetings today. Monday 5 July 2021 2 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Committees | Comataidhean Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. Monday 5 July 2021 3 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Future Meetings of the Parliament Business Programme agreed by the Parliament on 23 June 2021 Tuesday 31 August 2021 2:00 pm Time for Reflection followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions followed by Topical Questions (if selected) followed by First Minister’s Statement: Programme for Government 2021-22 followed by Committee Announcements followed by Business Motions followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions 5:00 pm Decision Time followed by Members' Business Wednesday 1 -

Official Report

Meeting of the Parliament (Hybrid) Thursday 3 June 2021 Session 6 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.parliament.scot or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Thursday 3 June 2021 CONTENTS Col. FIRST MINISTER’S QUESTION TIME ..................................................................................................................... 1 Scottish Qualifications Authority ................................................................................................................... 1 Covid-19 (Government Response) ............................................................................................................... 5 Green Recovery............................................................................................................................................ 9 European Union Settlement Scheme ......................................................................................................... 11 Schools (Maximum Class Sizes) ................................................................................................................ 12 Forced Adoption Apology ........................................................................................................................... 13 Police Officers (Burn-out) ........................................................................................................................... 16 Ferry Services (Stornoway to Ullapool) -

New Msps 2021

SPICe Fact Sheet Duilleagan Fiosrachaidh SPICe 25 May 2021 New MSPs 2021 This Fact Sheet provides a list of the newly elected MSPs to the Scottish Parliament during the election on 6 May 2021, with a note of the constituency (C) or region (R) they represent. The MSPs listed were not serving MSPs at the end of Session 5 of the Scottish Parliament. Party Abbreviation Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Con Scottish Green Party Green Scottish Labour Lab Scottish Liberal Democrats LD Scottish National Party SNP Independent MSPs Ind No Party Affiliation NPA Karen Adam (SNP) Banffshire and Buchan Coast (C) Siobhian Brown (SNP) Ayr (C) Ariane Burgess (Green) Highlands and Islands (R) Stephanie Callaghan (SNP) Uddingston and Bellshill (C) Maggie Chapman (Green) North East Scotland (R) Foysol Choudhury (Lab) Lothian (R) Katy Clark (Lab) West Scotland (R) Natalie Don (SNP) Renfrewshire North and West (C) New MSPs 2021 1 Sharon Dowey (Con) South Scotland (R) Jackie Dunbar (SNP) Aberdeen Donside (C) Pam Duncan-Glancy (Lab) Glasgow (R) Jim Fairlie (SNP) Perthshire South and Kinross-shire (C) Russell Findlay (Con) West Scotland (R) Meghan Gallacher (Con) Central Scotland (R) Pam Gosal (Con) West Scotland (R) Neil Gray (SNP) Airdrie and Shotts (C) Sandesh Gulhane (Con) Glasgow (R) Craig Hoy (Con) South Scotland (R) Stephen Kerr (Con) Central Scotland (R) Douglas Lumsden (Con) North East Scotland (R) Gillian Mackay (Green) Central Scotland (R) Michael Marra (Lab) North East Scotland (R) Màiri McAllan (SNP) Clydesdale (C) Paul McLennan (SNP) East -

Official Report and Is Subject to Correction Between Publication and Archiving, Which Will Take Place No Later Than 35 Working Days After the Date of the Meeting

DRAFT Meeting of the Parliament (Hybrid) Tuesday 31 August 2021 Session 6 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.parliament.scot or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Tuesday 31 August 2021 CONTENTS Col. TIME FOR REFLECTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 BUSINESS MOTION ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Motion moved—[George Adam]—and agreed to. TOPICAL QUESTION TIME ................................................................................................................................... 4 Classroom-based Learning (Covid-19) ........................................................................................................ 4 Support for Refugees (Afghanistan) ............................................................................................................. 6 SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT AGREEMENT WITH SCOTTISH GREEN PARTY ............................................................... 10 Statement—[First Minister]. JUNIOR MINISTERS .......................................................................................................................................... 31 Motion moved—[First Minister]. The First Minister (Nicola Sturgeon) .......................................................................................................... -

Election 2021

SPICe Briefing Pàipear-ullachaidh SPICe Election 2021 Andrew Aiton, Sarah Atherton, Ross Burnside, Allan Campbell, Nicola Hudson, Iain McIver and Emma Robinson This briefing analyses the result of the 2021 Scottish Parliament election. 10 May 2021 SB 21-24 Election 2021, SB 21-24 Contents The result ______________________________________________________________3 What does the result mean for Session 6?___________________________________6 Overview _____________________________________________________________6 Are there any patterns to the election results? ________________________________6 What does the result mean for the formation of the Scottish Government? __________7 Diversity ______________________________________________________________7 Turnout_______________________________________________________________7 What is the result likely to mean for the Session 6 Parliament? ___________________8 Comparison with previous parliaments _____________________________________9 State of the parties _____________________________________________________ 11 Constituency and regional list vote ________________________________________ 11 Composition of the Parliament ___________________________________________15 MSPs who did not re-stand for election _____________________________________15 MSPs who lost their seats at the 2021 election _______________________________16 New Members ________________________________________________________16 Gender______________________________________________________________19 Class of 1999_________________________________________________________20