Kent Nature Partnership Biodiversity Strategy 2020 to 2045

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

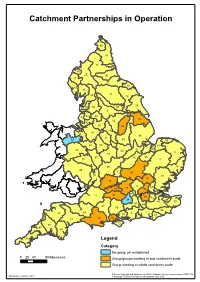

Catchment Partnerships in Operation

Catchment Partnerships in Operation 100 80 53 81 89 25 90 17 74 26 67 33 71 39 16 99 28 99 56 95 2 3 20 30 37 18 42 42 85 29 79 79 15 43 91 96 21 83 38 50 61 69 51 51 59 92 62 6 73 97 45 55 75 7 88 24 98 8 82 60 10 84 12 9 57 87 77 35 66 66 78 40 5 32 78 49 35 14 34 49 41 70 94 44 27 76 58 63 1 48 23 4 13 22 19 46 72 31 47 64 93 Legend Category No group yet established 0 20 40 80 Kilometres GSurobu cpa/gtcrhomupesn wt orking at sub catchment scale WGrhooulpe wcaotrckhinmge antt whole catchment scale © Crown Copyright and database right 2013. Ordnance Survey licence number 100024198. Map produced October 2013 © Copyright Environment Agency and database right 2013. Key to Management Catchment ID Catchment Sub/whole Joint ID Management Catchment partnership catchment Sub catchment name RBD Category Host Organisation (s) 1 Adur & Ouse Yes Whole South East England Yes Ouse and Adur Rivers Trust, Environment Agency 2 Aire and Calder Yes Whole Humber England No The Aire Rivers Trust 3 Alt/Crossens Yes Whole North West England No Healthy Waterways Trust 4 Arun & Western Streams Yes Whole South East England No Arun and Rother Rivers Trust 5 Bristol Avon & North Somerset Streams Yes Whole Severn England Yes Avon Wildlife Trust, Avon Frome Partnership 6 Broadland Rivers Yes Whole Anglian England No Norfolk Rivers Trust 7 Cam and Ely Ouse (including South Level) Yes Whole Anglian England Yes The Rivers Trust, Anglian Water Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Wildlife 8 Cherwell Yes Whole Thames England No Trust 9 Colne Yes Whole Thames England -

Join the Kent Wildlife Trust Lottery and Win for Wildlife

Join the Kent Wildlife Trust Lottery and Win for Wildlife Please return your completed form to: Membership, Kent Wildlife Trust, Tyland Barn, Sandling, Maidstone, Kent, ME14 3BD. We’ll write to you within 14 days to confirm your entry. Title Forenames Surname D.O.B. Address Postcode Telephone Email I am also happy to be contacted by Kent Wildlife Trust about their conservation, events, membership, fundraising and other activities by (please tick all that apply): Post Telephone Email Your details will be used for Kent Wildlife Trust’s purposes only and will not be sold or passed onto any other organisations. How many entries would you like each month? (please tick one box) 1 Entry per month (£2) 2 Entries per month (£4) 3 Entries per month (£6) 4 Entries per month (£8) 5 Entries per month (£10) 10 Entries per month (£20) Other amount of entries: Entries per month total £ Instruction to your Bank or Building Society to pay by Direct Debit Name and full postal address of your Bank or Building Society To: The Manager Bank/ Building Society Address Service user number 6 2 4 1 8 7 Postcode Reference L O T Name(s) of Account Holder(s) Instruction to Bank or Building Society Please pay Kent Wildlife Trust Direct Debits from the account detailed in this instruction subject to the safeguards assured by Account Number the Direct Debit Guarantee. I understand that this instruction may remain with Kent Wildlife Trust and, if so, details will be passed electronically to my Bank/Buildling Society. Sort Code Signature(s) Date Banks and Building Societies may not accept Direct Debit Instructions for some types of account. -

Birds, Butterflies & Wildflowers of the Dordogne

Tour Report France – Birds, Butterflies & Wildflowers of the Dordogne 15 – 22 June 2019 Woodchat shrike Lizard orchid Spotted fritillary (female) River Dordogne near Lalinde Compiled by David Simpson & Carine Oosterlee Images courtesy of: Mike Stamp & Corine Oosterlee 01962 302086 [email protected] www.wildlifeworldwide.com Tour Leaders: David Simpson & Corine Oosterlee Day 1: Arrive Bergerac; travel to Mauzac & short local walk Saturday 15 June 2019 It was a rather cool, cloudy and breezy afternoon as the Ryanair flight touched down at Bergerac airport. Before too long the group had passed through security and we were meeting one another outside the arrivals building. There were only five people as two of the group had driven down directly to the hotel in Mauzac, from their home near Limoges in the department of Haute-Vienne immediately north of Dordogne. After a short walk to the minibus we were soon heading off through the fields towards Mauzac on the banks of the River Dordogne. A song thrush sang loudly as we left the airport and some of us had brief views of a corn bunting or two on the airport fence, whilst further on at the Couze bridge over the River Dordogne, several crag martins were flying. En route we also saw our first black kites and an occasional kestrel and buzzard. We were soon parking up at the Hotel Le Barrage where Amanda, the hotel manager, greeted us, gave out room keys and helped us with the suitcases. Here we also met the other couple who had driven straight to the hotel (and who’d already seen a barred grass snake along the riverbank). -

Shepway Local Development Framework Green Infrastructure Report

EB 08.20 Shepway Local Development Framework Green Infrastructure Report Elham Park Wood Shepway Green Infrastructure Report July 2011 1 Contents 1. Green Infrastructure - definitions 2. Components of GI 3. Functions and benefits of GI 4. GI policy context 5. The GI resource in Shepway 6. Biodiversity GI in Shepway 7. Linear Feature GI 8. Civic Amenity GI 9. Key issues and opportunities in relation to strategic development sites Shepway Green Infrastructure Report July 2011 2 1. Green Infrastructure - definitions 1.1 A number of definitions of Green Infrastructure (GI) are in use including:- PPS12 – “…a network of multi-functional green space, both new and existing, both rural and urban, which supports the natural and ecological processes and is integral to the health and quality of life of sustainable communities.” 1.2 South East Plan/South East GI Partnership – “For the purposes of spatial planning the term green infrastructure (GI) relates to the active planning and management of sub-regional networks of multi-functional open space. These networks should be managed and designed to support biodiversity and wider quality of life, particularly in areas undergoing large scale change.“ 1.3 Natural England – “Green Infrastructure (GI) is a strategically planned and delivered network of high quality green spaces and other environmental features. It should be designed and managed as a multifunctional resource capable of delivering a wide range of environmental and quality of life benefits for local communities. Green Infrastructure includes parks, open spaces, playing fields, woodlands, allotments and private gardens.” 1.4 The common features of these definitions are that GI:- • involves natural and managed green areas in urban and rural settings • is about the strategic connection of open green areas • should provide multiple benefits for people 2. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A B ell & Howell Iiiformation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 University of Oklahoma Graduate College A Geography of Extinction: Patterns in the Contraction of Geographic Ranges A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Robert B. -

Butterflies of Croatia

Butterflies of Croatia Naturetrek Tour Report 11 - 18 June 2018 Balkan Copper High Brown Fritillary Balkan Marbled White Meleager’s Blue Report and images compiled by Luca Boscain Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Butterflies of Croatia Tour participants: Luca Boscain (leader) and Josip Ledinšćak (local guide) with 12 Naturetrek clients Summary The week spent in Croatia was successful despite the bad weather that affected the second half of the holiday. The group was particularly patient and friendly, having great enthusiasm and a keen interest in nature. We explored different habitats to find the largest possible variety of butterflies, and we also enjoyed every other type of wildlife encountered in the field. Croatia is still a rather unspoilt country with a lot to discover, and some almost untouched areas still use traditional agricultural methods that guaranteed an amazing biodiversity and richness of creatures that is lost in some other Western European countries. Day 1 Monday 11th June After a flight from the UK, we landed on time at 11.45am at the new Zagreb airport, the ‘Franjo Tuđman’. After collecting our bags we met Ron and Susan, who had arrived from Texas a couple of days earlier, Luca, our Italian tour leader, and Josip, our Croatian local guide. Outside the terminal building we met Tibor, our Hungarian driver with our transport. We loaded the bus and set off. After leaving Zagreb we passed through a number of villages with White Stork nests containing chicks on posts, and stopped along the gorgeous riverside of Kupa, not far from Petrinja. -

New Localities of Ophrys Insectifera (Orchidaceae) in Bulgaria

PROCEEDINGS OF THE BALKAN SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE OF BIOLOGY IN PLOVDIV (BULGARIA) FROM 19TH TILL 21ST OF MAY 2005 (EDS B. GRUEV, M. NIKOLOVA AND A. DONEV), 2005 (P. 312–320) NEW LOCALITIES OF OPHRYS INSECTIFERA (ORCHIDACEAE) IN BULGARIA Tsvetomir Tsvetanov1,*, Vladimir Vladimirov1, Antoaneta Petrova2 1 - Institute of Botany, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria 2 - Botanical Garden, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria * - address for correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Two new localities of Ophrys insectifera (Orchidaceae) has been found in the Buynovo and Trigrad gorges in the Central Rhodope Mountains. The species had been previously known from a single locality in the Golo Bardo Mountain, where only one specimen had been detected recently. Therefore, the species was considered as an extremely rare in the Bulgarian flora and included in the Annex 3 (Protected species) to the national Biodiversity Act. A total of ca. 25 individuals has been found in the two new localities. Assessment of the species against the IUCN Red List Criteria at national level resulted in a national category “Critically endangered” (CR C2a(i)+D), based on the very small number of individuals in the populations, the limited area of occupancy and severely fragmented locations. KEY WORDS: new chorological data, Ophrys, Orchidaceae, critically endangered species, Rhodope Mts INTRODUCTION Ophrys is among the taxonomically most intricate vascular plant genera in the European flora. Following the taxonomic concept of Delforge (1995) it is represented with 5 species in the Bulgarian flora - O. apifera Huds., O. cornuta Steven, O. insectifera L., O. reinholdii H. Fleischm. and O. mammosa Desf. (Assyov & al. -

Introduction

BULGARIA Nick Greatorex-Davies. European Butterflies Group Contact ([email protected]) Local Contact Prof. Stoyan Beshkov. ([email protected]) National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), Sofia, Butterfly Conservation Europe Partner Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Stanislav Abadjiev compiled and collated butterfly records for the whole of Bulgaria and published a Local Recording Scheme distribution atlas in 2001 (see below). Records are still being gathered and can be sent to Stoyan Beshkov at NMNH, Sofia. Butterfly List See Butterflies of Bulgaria website (Details below) Introduction Bulgaria is situated in eastern Europe with its eastern border running along the Black Sea coast. It is separated from Romania for much of its northern border by the River Danube. It shares its western border with Serbia and Macedonia, and its southern border with Greece and Turkey. Bulgaria has a land area of almost 111,000 sq km (smaller than England but bigger than Scotland) and a declining human population of 7.15 million (as of 2015), 1.5 million of which live in the capital city, Sofia. It is very varied in both climate, topography and habitats. Substantial parts of the country are mountainous, particularly in the west, south-west and central ‘spine’ of the country and has the highest mountain in the Balkan Mountains (Musala peak in the Rila Mountains, 2925m) (Map 1). Almost 70% of the land area is above 200m and over 27% above 600m. About 40% of the country is forested and this is likely to increase through natural regeneration due to the abandonment of agricultural land. Following nearly 500 years under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, Bulgaria was independent for just a few years from 1908 before coming under the domination of the soviet communist regime in 1946. -

Business Plan 2017-22

Bird Wise North Kent – Business Plan 2017-2022 1 Contents Contents ......................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................... 2 Vision and Objectives ..................................................... 3 Year 1 - Implementation 2017/18 .................................. 4 Year 2 - Delivery 2018/19 ............................................... 6 Continuation of Projects 2019-22 ................................ 10 Budget .......................................................................... 12 Bird Wise North Kent – Business Plan 2017-2022 2 Introduction The north Kent coastal habitat from Gravesend to Whitstable plays home to thousands of wading birds and waterfowl. For this reason, the Thames, Medway and Swale estuaries and marshes comprise of three Special Protection Areas (SPAs). All of these are also listed as Ramsar sites due to the international significance of the wetland habitats. Significant development is planned for north Kent with growing demand for new homes to accommodate the increasing population in the administrative areas of Canterbury, Dartford, Gravesham, Medway and Swale. With additional homes, the number of recreational visitors to the coastal areas will increase. Research has shown that the increasing numbers of visitors will have a negative impact on designated bird species. A strategic approach is required to deliver measures to mitigate any disturbance to birds caused by increased recreational activity. The -

Ophrys Insectifera L

Ophrys insectifera L. Fly Orchid A slender orchid of woodland edges, calcareous fens and other open habitats, Ophrys insectifera has distinctive flowers that lure pollinators by mimicry and the release of pheromones. Flowers have a velvety, purplish- brown labellum with an iridescent blue patch and a broad terminal lobe with two shining ‘pseudoeyes’, and very narrow petals resembling a pair of antennae. Its British strongholds are in the south and east of England. Elsewhere it is scattered across the Midlands, northern England and southern Ireland, rare in Wales, and absent from Scotland. Substantial declines throughout its range have led to an assessment of Vulnerable in Great Britain. ©Pete Stroh IDENTIFICATION 2011). The (2-5) unspotted elliptic-oblong leaves from which the flowering spike arises have a shiny, bluish-green Ophrys insectifera stems can reach 60 cm in height but are appearance. often difficult to spot amid the surrounding vegetation. Three yellow-green sepals contrast with the much smaller (less than half as long) vertical, slender purplish-brown labellum which SIMILAR SPECIES has a velvety texture (Stace 2010) due to short, fine, downy The distinctive lateral lobes, filiform petals, and slender hairs. appearance of the labellum should readily separate it from The labellum has two narrow side lobes spreading outwards other Ophrys species. In rare instances, individuals of O. and a broad terminal lobe which is notched at the tip and has insectifera lack normal pigmentation (e.g. white sepals; two shining ‘pseudoeyes’ (Harrap & Harrap 2009). Flowers greenish-yellow patterning on the labellum). Natural also have a distinctive iridescent blue patch on the speculum, hybridization between O. -

Adaptation to Climate Change Sustainable Local Economies Abundant Wildlife Healthy Cities and Green Space for All

A living landscape A call to restore the UK’s battered ecosystems, for wildlife and people Adaptation to climate change Sustainable local economies Abundant wildlife Healthy cities and green space for all Updated with 100+ Living Landscape schemes So much of the UK now is packed with development Fenton/BBC Beatrice and wildlife is in retreat. There are many fine nature A LIVING LANDSCAPE reserves but our future must be to integrate human and natural communities and restore a better balance. This document lays out exciting and important new plans. Professor Aubrey Manning OBE President of The Wildlife Trusts Matthew Roberts. Cover picture: St Ives and the river Great Ouse, Cambridgshire, Dae Sasitorn/lastrefuge.co.uk Dae Cambridgshire, Ouse, Great river the and Ives St picture: Cover Roberts. Matthew Where will our water come from? When will our land use become truly sustainable? How can our environment adapt to climate change? What would it take to rebuild a wildlife-rich countryside? Why are so many people disconnected from nature? Priestcliffe Lees nature reserve, owned by Derbyshire Wildlife Trust: a treasure chest of local biodiversity. The Wildlife Trusts see such places as nodes from It’s time to think big which plants and animals can recolonise a recovering landscape To adapt to climate change, the UK’s wildlife will need to move Driven by local people and aspirations, The Wildlife Trusts play along ‘climate corridors’ up and down the country, or to shadier a leading role not just in developing the vision but in mustering slopes or cooler valleys. Wildlife has done it all before, after the the support that can allow communities to drive their own last ice age, but this time the change is faster and there are change. -

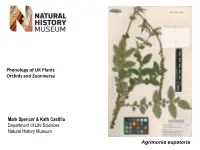

Orchid Observers

Phenology of UK Plants Orchids and Zooniverse Mark Spencer & Kath Castillo Department of Life Sciences Natural History Museum Agrimonia eupatoria Robbirt & al. 2011 and UK specimens of Ophrys sphegodes Mill NHM Origins and Evolution Initiative: UK Phenology Project • 20,000 herbarium sheets imaged and transcribed • Volunteer contributed taxonomic revision, morphometric and plant/insect pollinator data compiled • Extension of volunteer work to extract additional phenology data from other UK museums and botanic gardens • 7,000 herbarium sheets curated and mounted • Collaboration with BSBI/Herbaria@Home • Preliminary analyses of orchid phenology underway Robbirt & al. (2011) . Validation of biological collections as a source of phenological data for use in climate change studies: a case study with the orchid Ophrys sphegodes. J. Ecol. Brooks, Self, Toloni & Sparks (2014). Natural history museum collections provide information on phenological change in British butterflies since the late-nineteenth century. Int. J. Biometeorol. Johnson & al. (2011) Climate Change and Biosphere Response: Unlocking the Collections Vault. Bioscience. Specimens of Gymnadenia conopsea (L.) R.Br Orchid Observers Phenology of UK Plants Orchids and Zooniverse Mark Spencer & Kath Castillo Department of Life Sciences Natural History Museum 56 species of wild orchid in the UK 29 taxa selected for this study Anacamptis morio Anacamptis pyramidalis Cephalanthera damasonium Coeloglossum viride Corallorhiza trifida Dactylorhiza fuchsii Dactylorhiza incarnata Dactylorhiza maculata Dactylorhiza praetermissa Dactylorhiza purpurella Epipactis palustris Goodyera repens Gymnadenia borealis Gymnadenia conopsea Gymnadenia densiflora Hammarbya paludosa Herminium monorchis Neotinea ustulata Neottia cordata Neottia nidus-avis Neottia ovata Ophrys apifera Ophrys insectifera Orchis anthropophora Orchis mascula Platanthera bifolia Platanthera chlorantha Pseudorchis albida Spiranthes spiralis Fly orchid (Ophrys insectifera) Participants: 1.