RLC001 Coachtalk 2007(V2).Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

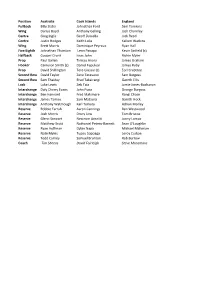

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater Johnathan Ford Sam Tomkins Wing Darius Boyd Anthony Gelling Josh Charnley Centre Greg Inglis Geoff Daniella Jack Reed Centre Justin Hodges Keith Lulia Kallum Watkins Wing Brett Morris Dominique Peyroux Ryan Hall Five Eighth Johnathan Thurston Leon Panapa Kevin Sinfield (c) Halfback Cooper Cronk Issac John Richie Myler Prop Paul Gallen Tinirau Arona James Graham Hooker Cameron Smith (c) Daniel Fepuleai James Roby Prop David Shillington Tere Glassie (c) Eorl Crabtree Second Row David Taylor Zane Tetevano Sam Burgess Second Row Sam Thaiday Brad Takairangi Gareth Ellis Lock Luke Lewis Zeb Taia Jamie Jones-Buchanan Interchange Daly Cherry Evans John Puna George Burgess Interchange Ben Hannant Fred Makimare Rangi Chase Interchange James Tamou Sam Mataora Gareth Hock Interchange Anthony Watmough Karl Temata Adrian Morley Reserve Robbie Farrah Aaron Cannings Ben Westwood Reserve Josh Morris Drury Low Tom Briscoe Reserve Glenn Stewart Neccrom Areaiiti Jonny Lomax Reserve Matthew Scott Nathaniel Peteru-Barnett Sean O'Loughlin Reserve Ryan Hoffman Dylan Napa Michael Mcllorum Reserve Nate Myles Tupou Sopoaga Leroy Cudjoe Reserve Todd Carney Samuel Brunton Rob Burrow Coach Tim Sheens David Fairleigh Steve Mcnamara Fiji France Ireland Italy Jarryd Hayne Tony Gigot Greg McNally James Tedesco Lote Tuqiri Cyril Stacul John O’Donnell Anthony Minichello (c) Daryl Millard Clement Soubeyras Stuart Littler Dom Brunetta Wes Naiqama (c) Mathias Pala Joshua Toole Christophe Calegari Sisa Waqa Vincent -

Penrith District Rugby League Football Club 2013 Annual Report

Annual Report Penrith District Rugby League Football Club Limited 2013 AnnUAL REPort 2013 CONTENTS 3 REPorts & REVIEWS Corporate Information 5 General Manager’s Report 6 C OMPanY ProFILE Sponsors 2013 8 AnnUAL FInancIAL REPort PenrITH DISTRICT RUGBY LEAGUE FootBALL CLUB LIMIted MEMBERSHIP FROM Director’s Report 9 * Life Members 12 Auditor’s Independence Declaration 13 Statement of Comprehensive Income 14 $6 PER GAME Statement of Financial Position 15 Statement of Changes in Equity 16 SAVE UP TO 67% ON GATE PRICES Statement of Cash Flows 17 Notes to the Financial Statements 18 AFFORDABLE PAYMENT PLANS Director’s Declaration 31 EXCLUSIVE MEMBERS Independent Auditor’s Report 32 MERCHANDISE MEMBER ONLY EVENTS CALL 1300-PANTHERS OR GO TO MEMBERSHIP.PENRITHPANTHERS.COM.AU *SPEAK TO OUR MEMBERSHIP TEAM TO SEE WHAT OPTION BEST SUITS YOU AnnUAL REPort 2013 AnnUAL REPort 2013 4 CorPorate 5 INFORMatIon ACN 003 908 503 Directors D. Feltis JP - Chairman T. Heidtmann - Senior Deputy Chairman (Deceased 13.8.13) J. Hiatt OAM - Deputy Chairman B. Fletcher - Deputy Chairman (Appointed 28.8.13) G. Alexander K. Lowe (Resigned 30.1.13) D. Merrick FCPA/JP D. O’Neill (Appointed 30.1.13) K. Rhind OAM S. Robinson Registered Office Mulgoa Road Penrith NSW 2750 Company Secretary W Wilson Bankers ANZ Auditors Ernst & Young National Youth Competition: Under 20’s Premier’s 2013 AnnUAL REPort 2013 AnnUAL REPort 2013 6 EXECUTIVE GeneraL EXECUTIVE GeneraL 7 ManaGER'S REPORT ManaGER'S REPORT CONTINUED In last year’s Annual Report, I described 2012 I would like to take this opportunity to in great shape and I personally thank Keith for as “a year of significant change” for our rugby congratulate our General Manager of Rugby the guidance and friendship he has extended to league club, where “solid foundations have been League Mr Phil Moss on the outstanding work he everyone whose lives he has touched over the put in place for the long term future of the club”. -

National Code of Conduct

Rugby League’s Values Excellence Inclusiveness » Valuing the importance of every » Engaging and empowering everyone decision and every action to feel welcome in our game » Striving to improve and innovate » Reaching out to new participants and in everything we do supporters » Setting clear goals against which » Promoting equality of opportunity in we measure success all its forms » Inspiring the highest standards in » Respecting and celebrating diversity in ourselves and others culture, gender and social background Courage Teamwork » Standing up for our beliefs and » Encouraging and supporting others empowering others to do the same to achieve common goals » Being prepared to make a » Committing to a culture of honesty difference by leading change and trust » Putting the game ahead of » Motivating those around us to individual needs challenge themselves » Having the strength to make the » Respecting the contribution of right decisions, placing fact ahead every individual of emotion Rugby League Central Driver Avenue, Moore Park NSW 2021 Published 2014 T: 02 9359 8500 W: www.nrl.com NATIONAL CODE OF CONDUCT NATIONAL CODE OF CONDUCT Introduction The Rugby League Code of Conduct provides all participants – players, parents, coaches, referees, spectators and officials – with some simple rules that assist in delivering a safe and positive environment to everyone involved in the game. Within that safe environment, every Rugby League participant has the best chance to enjoy the game. By accepting the standards of behaviour in the Code, we provide opportunities for young boys and girls to grow on the field - we build good players, good citizens and good communities in which Rugby League is a social asset. -

Heighington Ready to Make a Comeback for Tigers

SPORT sundayterritorian.com.au Plum ripe for Penrith HE’S had a career blighted Dragons fire late by injuries and bad luck, but it’s been a week of celebration for Penrith enforcer Nigel Plum. The 29-year-old is widely acknowledged as one of the biggest hitters in the game, but since making his debut to deny Parramatta for Sydney Roosters in 2005, the second-rower has been plagued by injuries DRAGONS V EELS and has made just 82 NRL appearances. A LATE try from centre Kyle He enjoyed a strong Stanley gave St George season last year, playing 20 Illawarra a hard-fought games and was rewarded 14-12 win over a gallant with a new two-year deal. Parramatta side at Kogarah However, his injury curse — breaking the Dragons’ struck again when he sus- three-game losing streak. tained a serious shoulder in- The desperate Dragons jury at training, requiring kept the ball alive to allow the more surgery. powerful centre to crash over But after becoming a fath- on the right edge. er for the second time on Stanley had also opened his Tuesday, Plum then found team’s scoring with a try in out later that day he was be- PUB: the 20th minute. ing thrown back into first But home fans were made grade by Panthers coach to sweat right to the end with Ivan Cleary for today’s clash winger Daniel Vidot defusing with Manly at Centrebet NT NEWS a towering Jarryd Hayne Stadium. bomb near his own goal-line ‘‘It’s been a fantastic seconds before full-time. -

WESTS TIGERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL V NATIONAL RUGBY LEAGUE – the CASE THAT COULD HAVE STOPPED the NRL

2011 6(1) Australian and New Zealand Sports Law Journal 1 WESTS TIGERS RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL v NATIONAL RUGBY LEAGUE – THE CASE THAT COULD HAVE STOPPED THE NRL David Trodden* ‘It could cost us £30 million but what can we do? He’s given a goal.’ This was Tottenham Hotspur manager Harry Redknapp speaking after a refereeing error resulted in a goal being awarded against his team when the ball clearly didn’t cross the goal line. It was in a crucial end of season match against Chelsea in the English Premier League. Spurs lost the match 2–1, negatively affecting their prospects of qualifying for the European Champions League in the following season.1 ‘What can we do’ asks Harry? ‘You can’t sue a referee’ I hear you say. Why not? Everyone else is liable for their mistakes. Why not a referee? Is there any principle of law which prevents a referee from being sued? This article attempts to examine what Harry Redknapp, and those in similar situations, can do. It examines the possibility of taking action to correct an incorrect refereeing decision. It also considers, in a far briefer and more general sense, the possibility of recovering damages in circumstances where the decision can’t be corrected. Wests Tigers found themselves in a similar situation to Tottenham Hotspur when a refereeing error cost them the chance of playing in the 2010 National Rugby League (‘NRL’) Grand Final. This is what they could have done. Introduction On 25 September 2010, Wests Tigers played against St George Illawarra Dragons at ANZ Stadium in Sydney, in the preliminary final of the National Rugby League Competition. -

RAM Index As at 1 September 2021

RAM Index As at 1 September 2021. Use “Ctrl F” to search Current to Vol 74 Item Vol Page Item Vol Page This Index is set out under the Aircraft armour 65 12 following headings. Airbus A300 16 12 Airbus A340 accident 43 9 Airbus A350 37 6 Aircraft. Airbus A350-1000 56 12 Anthony Element. Airbus A400 Avalon 2013 2 Airbus Beluga 66 6 Arthur Fry Airbus KC-30A 36 12 Bases/Units. Air Cam 47 8 Biographies. Alenia C-27 39 6 All the RAAF’s aircraft – 2021 73 6 Computer Tips. ANA’s DC3 73 8 Courses. Ansett’s Caribou 8 3 DVA Issues. ARDU Mirage 59 5 Avro Ansons mid air crash 65 3 Equipment. Avro Lancaster 30 16 Gatherings. 69 16 General. Avro Vulcan 9 10 Health Issues. B B2 Spirit bomber 63 12 In Memory Of. B-24 Liberator 39 9 Jeff Pedrina’s Patter. 46 9 B-32 Dominator 65 12 John Laming. Beaufighter 61 9 Opinions. Bell P-59 38 9 Page 3 Girls. Black Hawk chopper 74 6 Bloodhound Missile 38 20 People I meet. 41 10 People, photos of. Bloodhounds at Darwin 48 3 Reunions/News. Boeing 307 11 8 Scootaville 55 16 Boeing 707 – how and why 47 10 Sick Parade. Boeing 707 lost in accident 56 5 Sporting Teams. Boeing 737 Max problems 65 16 Squadrons. Boeing 737 VIP 12 11 Boeing 737 Wedgetail 20 10 Survey results. Boeing new 777X 64 16 Videos Boeing 787 53 9 Where are they now Boeing B-29 12 6 Boeing B-52 32 15 Boeing C-17 66 9 Boeing KC-46A 65 16 Aircraft Boeing’s Phantom Eye 43 8 10 Sqn Neptune 70 3 Boeing Sea Knight (UH-46) 53 8 34 Squadron Elephant walk 69 9 Boomerang 64 14 A A2-295 goes to Scottsdale 48 6 C C-130A wing repair problems 33 11 A2-767 35 13 CAC CA-31 Trainer project 63 8 36 14 CAC Kangaroo 72 5 A2-771 to Amberley museum 32 20 Canberra A84-201 43 15 A2-1022 to Caloundra RSL 36 14 67 15 37 16 Canberra – 2 Sqn pre-flight 62 5 38 13 Canberra – engine change 62 5 39 12 Canberras firing up at Amberley 72 3 A4-208 at Oakey 8 3 Caribou A4-147 crash at Tapini 71 6 A4-233 Caribou landing on nose wheel 6 8 Caribou A4-173 accident at Ba To 71 17 A4-1022 being rebuilt 1967 71 5 Caribou A4-208 71 8 AIM-7 Sparrow missile 70 3 Page 1 of 153 RAM Index As at 1 September 2021. -

CONTENTS Book 2 Coach Talk Graham Murray - Sydney Roosters Head Coach 2001 21

RLCMRLCMRLCM Endorsed By Visit www.rlcm.com.au RUGBY LEAGUE COACHING MANUALS CONTENTS Book 2 Coach Talk Graham Murray - Sydney Roosters Head Coach 2001 21 5 The Need for Innovation & Creativity in Rugby League Source of information - Queensland Rugby League Coaching Camp, Gatton 2001 Level 2 Lectures By Dennis Ward & Don Oxenham Written by Robert Rachow 9 Finding The Edge Steve Anderson - Leeds Performance Director Written by David Haynes 11 Some Basic Principles in Defence and Attack By Shane McNally - Northern Territory Institute of Sport Coaching Director 14 The Roosters Recruitment Drive Brian Canavan - Sydney Roosters Football Manager Written By David Haynes 16 Session Guides By Bob Woods - ARL Level 2 Coach 22 Rugby League’s Battle for Great Britain By Rudi Meir - Senior Lecturer in Human Movements Southern Cross University 27 Injury Statistics By Doug King RCpN, Dip Ng, L3 NZRL Trainer, SMNZ Sports Medic 33 Play The Ball Drills www.rlcm.com.au Page 1 Coach Talk GRAHAM MURRAY - Head Coach Sydney Roosters RLFC Graham Murray is widely recognised within Rugby League circles as a team builder, with the inherent ability to draw the best out of his player’s week in and week out. Murray has achieved success at all levels of coaching. He led Penrith to a Reserve Grade Premiership in 1987; took Illawarra to a major semi-final and Tooheys Challenge Cup victory in 1992; coached the Hunter Mariners to an unlikely World Club Challenge final berth in 1997; was the brains behind Leeds’ English Super League triumph in 1999; and more recently oversaw the Sydney Roosters go within a whisker of notching their first premiership in 25 years. -

National Coaches Conference 2018 PROGRAM 2 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 3 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018

National Coaches Conference 2018 PROGRAM 2 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 3 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 National Coaches Conference Program NRL Welcome 4 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 National Coaches Conference Program NRL Welcome Luke Ellis Head of Participation, Pathways & Game Development Welcome to the 2018 NRL National Coaching Conference, the largest coach development event on the calendar. In the room, there are coaches working with our youngest participants right through to our development pathways and elite level players. Each of you play an equally significant role in the development and future of the players in your care, on and off the field. Over the weekend, you will get the opportunity to hear from some remarkable people who have made a career out of Rugby League and sport in general. I urge you to listen, learn, contribute and enjoy each of the workshops. You will also have a fantastic opportunity to network and share your knowledge with coaches from across the nation and overseas. Coaches are the major influencer on long- term participation and enjoyment of every player involved in Rugby League. As a coach, it is our job to create a positive environment where the players can have fun, enjoy time with their friends, develop their skills, and become better people. Coaches at every level of the game, should be aiming to improve the CONFIDENCE, CHARACTER, COMPETENCE and CONNECTIONS with our players. Remember… It’s not just what you coach… It’s HOW you coach. Enjoy the weekend, Luke Ellis 5 NRL National Coaches Conference Program 2018 National Coaches Conference Program NRL Andrew Voss Event MC Now referred to as a media veteran in rugby league circles, Andrew is a sport and news presenter, commentator, writer and author. -

Queensland Rugby Football League Limited Notice of General Meeting 2 Directors 2 Directors’ Meetings 3 Chairman’S Report 2011 4

2011 queensland rugby football league limited Notice of General Meeting 2 Directors 2 Directors’ Meetings 3 Chairman’s Report 2011 4 Rebuilding Rugby League Campaign 6 Ross Livermore 7 Tribute to Queensland Representatives 8 Major Sponsors 9 ARL Commission 10 Valé Arthur Beetson 11 Valé Des Webb 12 State Government Support 13 Volunteer Awards 13 Queensland Sport Awards 13 ASADA Testing Program 14 QRL Website 14 Maroon Members 14 QRL History Committee 16 QRL Referees’ Board 17 QRL Juniors’ Board 18 Education & Development 20 Murri Carnival 21 Women & Girls 23 Contents ARL Development 24 Harvey Norman State of Origin Series 26 XXXX Queensland Maroons State of Origin Team 28 Maroon Kangaroos 30 Queensland Academy of Sport 31 Intrust Super Cup 32 Historic Cup Match in Bamaga 34 XXXX Queensland Residents 36 XXXX Queensland Rangers 37 Queensland Under 18s 38 Under 18 Maroons 39 Queensland Under 16s 40 Under 16 Maroons 41 Queensland Women’s Team 42 Cyril Connell & Mal Meninga Cups 43 A Grade Carnival 44 Outback Matches 44 Schools 45 Brisbane Broncos 46 North Queensland Cowboys 47 Gold Coast Titans 47 Statistics 2011 47 2011 Senior Premiers 49 Conclusion 49 Financials 50 Declarations 52 Directors’ Declaration 53 Auditors’ Independence Declaration 53 Independent Auditors’ Report 54 Statement of Comprehensive Income 55 Balance Sheet 56 Statement of Changes in Equity 57 Statement of Cash Flows 57 Notes to the Financial Statements 58 1 NOTICe of general meeting direCTORS’ meetings Notice is hereby given that the Annual 2. To appoint the Directors for the 2012 year. NUMBER OF MEETINGS NUMBER OF MEETINGS DIRECTOR General Meeting of the Queensland Rugby 3. -

OZ17 Brochure (Official)

In association with RUGBY LEAGUE WORLD CUP 2017 Australia & New Zealand Package Tours Official sub-agent Millshaw | Leeds | West Yorkshire | LS11 8EG Telephone 0113 242 2202 WELCOME For the fifth time in the past decade, sports travel specialists Traveleads and vastly-experienced Rugby League personality David Howes are in partnership to offer a high quality England supporters tour for the discerning International Rugby League aficionado. The Rugby League World Cup is the pinnacle of the 13-a-side code’s event calendar on a four-year cycle, the 2017 tournament being staged in Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea. YOUR HOSTS Traveleads, the UK’s top sports travel company, currently assists over 40 national governing bodies of sport and professional athletes. Our history with Rugby League and the RFL, (to whom we are still the appointed travel management company), dates back 32 years to the 1984 Great Britain Tour Down Under. Our remit also includes arranging the travel for the Super League and League One teams travelling to France for their away fixtures against Catalan Dragons and Toulouse Olympique. For company information please visit our website - www.traveleads.co.uk. Traveleads is working as a sub-agent of RLWC2017 Official Travel Agent, Glory Days UK. - see page 6 for more information Howes Etc was formed in the autumn of 2002 by Managing Director David Howes, who recently celebrated 40 years of top flight Rugby League management. David has the unique track record of performing with a national governing body, The Rugby Football League, from 1974 to 1994; a leading UK Rugby League club, St Helens, from 1995 to 1998; and one of the world’s heritage sporting venues, Headingley Stadium in Leeds, from 1998 to 2002. -

Summer 2019 Former Origin Greats Contents

Official Magazine of Queensland’s Former Origin Greats EDITION 31 | SUMMER 2019 FORMER ORIGIN GREATS CONTENTS A Message From is proudly sponsored by The Executive Chairman 3 Bartons Help Give The ARTIE Academy The Drive To Succeed 4 Cooper-Doodle-Doo! 5 Finally, Our Queensland Girls Get Their Time In The Sun 6 Cam Storms To Immortality 8 formally known as AEG Ogden FOGS Stay Close To The Heart Of Every Footballer In Queensland 11 Maroon Spirit Proves Too Hard For QLD Government To Ignore 12 From The Coach’s Desk With Kevin Walters 14 FOGS Origin Lunch Delivers For The Common Good 16 Daly Cherry-Evans 18 Queensland’s Future Is Now As Rookies Answer The Call 20 Holmes Is Where The Heart Is And It’s Great News For Maroons 21 Shaune Celebrates Half A Million Smiles On Queensland Faces 22 Queenslander Magazine, the official magazine of the Goodbye To The Greats Of A Golden Era 24 Former Origin Greats, is proudly printed by: Inspirational Artie Students Pay It Forward Through Prosocial Incentive Program 27 All For Fun, And Fun For All 28 RACQ And FOGS On The Road Again 30 T 07 3356 0788 E [email protected] Where Are They Now FOG #147 Ty Williams 32 A Unit7/36 Windorah St, Stafford QLD 4053 Tackle One www.crystalmedia.com.au With Trevor Gillmeister 35 CONTACT US FOGS LTD FAX FACEBOOK Locked Bag 3, Milton, QLD 4064 (07) 3367 8148 www.facebook.com/FOGSQueensland PHONE EMAIL INSTAGRAM (07) 3367 1432 [email protected] @qld_fogs 2 | www.fogs.com.au A MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN f rugby league has taught us anything, it is that the hard yards must be done before the rewards can be enjoyed. -

100 Years of Cabramatta Rugby League Football Club Gateway Home of the Two Blues to Grade

Gateway to Grade 100 years of Cabramatta Rugby League Football Club Gateway Home of The Two Blues to Grade Cabramatta Rugby League Club 24 Sussex Street, Cabramatta New South Wales 2166 Fairfieldcity Open Libraries Exhibition Gateway The First Game to Grade The first game was played 7 June 1919 against Liverpool Pewits. Cabra-Vale won 8-3. The players weight was restricted to under 54 Kg. Article from Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate Saturday 14 June 1919 Fairfieldcity Open Libraries Exhibition Gateway President of The Club to Grade Alderman George Stimson was the first president of the club which was called Cabra-Vale United Football Club. Vice presidents included four other aldermen including the Mayor of Cabramatta & Canley Vale Jacob Cook. Fairfieldcity Open Libraries Exhibition Gateway The Club Colours to Grade The club colours were royal and sky blue. Its home ground originally was Cabravale Park. In 1947, the club moved to Lunn’s Paddock, a dairy on what is now Sussex Street Cabramatta. Fairfieldcity Open Libraries Exhibition Gateway The Hey Brothers to Grade The Hey family lived on Pritchard Street, Mount Pritchard in 1926. They then moved to John St Cabramatta. Hey family Cabramatta Dave standing on left, Vic sitting on right Courtesy Fairfield City Open Libraries, Heritage Collection In 1925, Dave Hey played for the club and was the clubs first 1st Grade player, playing with Wests in 1926. Vic Hey c.1930s Courtesy State Library Queensland Vic Hey Courtesy thebulldogs.com.au In the late 40’s, early 50’s A-Grade was coached by league great, Vic Hey, the brother of Dave Hey.