Shakespeare in Small Places: with Particular Reference to Ten Productions, 1990 to 1995

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Freeman

First Assistant Director Peter Freeman 30 Birch Grove Windsor, Berks SL4 5RT Tel : +44 (0)1753 862226 Mobile: +44 (0)7774 700 747 SA Mobile: +27 (0)76 4377 963 e-mail: [email protected] Languages: Greek, Basic French Over 12 years experience with Movie Magic Scheduling. South African ResidenceVisa. Advanced Production Safety Certificate, BBC Total Concept Safety Certificate Recent credits include: FEATURES “Gulliver’s Travels” Jack Black as Gulliver in modern retelling of classic tale. (Additional Assistant Director) Cast Inc: Jack Black, Jason Segel, Billy Connolly, Emily Blunt. Directors: Chris O’Dell (2nd Unit), UPM/1st AD: Terry Bamber (2nd Unit), “Broken Thread” Modern day ghost story. Shot in India, Isle of Man and London. Cast inc: Linus Roache, Saffron Burrows Director: Mahesh Matai Producer: Deepak Nayar A.P: Paul Sarony “These Foolish Things” Romantic comedy set in 1920’s theatre-land. Shot in and around Cheltenham. Cast inc: Angelica Huston, Lauren Bacall, Terence Stamp, Andrew Lincon. Director: Julia Taylor-Stanley Producers: Julia Taylor-Stanley, Paul Sarony “Spirit Trap” Horror/ghost story. Shot in Romania and the UK for Archangel Productions. Cast inc: Luke Mably, Sam Troughton, Emma Catherwood and Billy Piper. Director: David Smith Producer: Susie Brooks-Smith A.P: David Higginson / Cathy Lord “Chasing Liberty” Second unit Czech Republic. Cast inc: Mandy Moore, Mark Harmon Director: Andy Cadiff (main unit) Line Prod: Cathy Lord A.P: Hilary Benson “Jane Eyre” Retelling of classic tragic love story. Derbyshire & London Cast inc: William Hurt, Charlotte Gainsburg, Elle Macpherson Director: Franco Zeffirelli Producer: Dyson Lovell A.P: Ray Freeborn Page 2 “Soft Sand, Blue Sea” Film Four. -

Shakespeare Survey: 64: Shakespeare As Cultural Catalyst Edited by Peter Holland Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-50536-6 - Shakespeare Survey: 64: Shakespeare as Cultural Catalyst Edited by Peter Holland Frontmatter More information SHAKESPEARE SURVEY © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-50536-6 - Shakespeare Survey: 64: Shakespeare as Cultural Catalyst Edited by Peter Holland Frontmatter More information ADVISORY BOARD Jonathan Bate Akiko Kusunoki Margreta de Grazia Kathleen McLuskie Janette Dillon Lena Cowen Orlin Michael Dobson Simon Palfrey Andrew Gurr Richard Proudfoot Ton H oe n se la ar s Emma Smith Andreas Hofele¨ Ann Thompson Russell Jackson Stanley Wells John Jowett Assistants to the Editor Catherine Clifford and Ethan Guagliardo (1) Shakespeare and his Stage (35) Shakespeare in the Nineteenth Century (2) Shakespearian Production (36) Shakespeare in the Twentieth Century (3) The Man and the Writer (37) Shakespeare’s Earlier Comedies (4) Interpretation (38) Shakespeare and History (5) Textual Criticism (39) Shakespeare on Film and Television (6) The Histories (40) Current Approaches to Shakespeare through (7) Style and Language Language, Text and Theatre (8) The Comedies (41) Shakespearian Stages and Staging (with an index (9) Hamlet to Surveys 31–40) (10) The Roman Plays (42) Shakespeare and the Elizabethans (11) The Last Plays (with an index to Surveys 1–10) (43) The Tempest and After (12) The Elizabethan Theatre (44) Shakespeare and Politics (13) King Lear (45) Hamlet and its Afterlife (14) Shakespeare and his Contemporaries (46) Shakespeare -

The North Face of Shakespeare: Activities for Teaching the Plays

Vol. XXIV Clemson University Digital Press Digital Facsimile Vol. XXIV THE • VPSTART • CROW• Contents Part One: Shakespeare's Jests and Jesters John R.. Ford • Changeable Taffeta: Re-dressing the Bears in Twelfth Night . 3 Andrew Stott • "The Fondness, the Filthinessn: Deformity and Laughter in Early-Modem Comedy........................................................................... 15 Tamara Powell and Sim Shattuck • Looking for Liberation and Lesbians in Shakespeare's Cross-Dressing Comedies ...................... ...................... 25 Rodney Stenning Edgecombe • "The salt fish is an old coar' in The Merry Wives of Windsor 1. 1 ................................•.....•..... .......•. ... ...... ......... ..... 34 Eve-Marie Oesterlen • Why Bodies Matter in Mouldy Tales: Material (Re)Tums in Pericles, Prince of Tyre .......................... ...... ...... ......... ... ................... 36 Gretchen E. Minton • A Polynesian Shakespeare Film: The Maori Merchant of Venice ............................................................................................... 45 Melissa Green • Tribal Shakespeare: The Federal Theatre Project's "Voo- doo Macbeth n(1936) ........................................ ...... ......... ... ............... .... 56 Robert Zaller • "Send the Head to Angelon: Capital Punishment in Measure for Measure ................................................................................:......... 63 Richard W. Grinnell • Witchcraft, Race, and the Rhetoric of Barbarism in Othello and 1 Henry IV......................................................................... -

THE 42Nd COMPARATIVE DRAMA CONFERENCE the Comparative Drama Conference Is an International, Interdisciplinary Event Devoted to All Aspects of Theatre Scholarship

THE 42nd COMPARATIVE DRAMA CONFERENCE The Comparative Drama Conference is an international, interdisciplinary event devoted to all aspects of theatre scholarship. It welcomes papers presenting original investigation on, or critical analysis of, research and developments in the fields of drama, theatre, and performance. Papers may be comparative across disciplines, periods, or nationalities, may deal with any issue in dramatic theory and criticism, or any method of historiography, translation, or production. Every year over 170 scholars from both the Humanities and the Arts are invited to present and discuss their work. Conference participants have come from over 35 countries and all fifty states. A keynote speaker whose recent work is relevant to the conference is also invited to address the participants in a plenary session. The Comparative Drama Conference was founded by Dr. Karelisa Hartigan at the University of Florida in 1977. From 2000 to 2004 the conference was held at The Ohio State University. In 2005 the conference was held at California State University, Northridge. From 2006 to 2011 the conference was held at Loyola Marymount University. Stevenson University was the conference’s host from 2012 through 2016. Rollins College has hosted the conference since 2017. The Conference Board Jose Badenes (Loyola Marymount University), William C. Boles (Rollins College), Miriam M. Chirico (Eastern Connecticut State University), Stratos E. Constantinidis (The Ohio State University), Ellen Dolgin (Dominican College of Blauvelt), Verna Foster (Loyola University, Chicago), Yoshiko Fukushima (University of Hawai'i at Hilo), Kiki Gounaridou (Smith College), Jan Lüder Hagens (Yale University), Karelisa Hartigan (University of Florida), Graley Herren (Xavier University), William Hutchings (University of Alabama at Birmingham), Baron Kelly (University of Louisville), Jeffrey Loomis (Northwest Missouri State University), Andrew Ian MacDonald (Dickinson College), Jay Malarcher (West Virginia University), Amy Muse (University of St. -

Shakespeare and Violence

SHAKESPEARE AND VIOLENCE R. A. FOAKES The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge , United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, ,UK West th Street, New York, -, USA Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, , Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on , Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town , South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C R. A. Foakes This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville Monotype /. pt System LATEX ε [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the B ritish Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Foakes, R. A. Shakespeare and Violence / R. A. Foakes. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. --- – --- (pb.) . Shakespeare, William, – – Views on violence. Shakespeare, William, – – Views on war. Violence in literature. War in literature. Title. . –dc hardback paperback Contents List of illustrations page ix Preface xi . Introduction: ‘Exterminate all the brutes’ . Shakespeare’s culture of violence Shakespeare and classical violence Shakespeare and Christian violence . Shakespeare and the display of violence Marlowe and the Rose spectaculars Shakespeare’s chronicles of violence: Henry VI, Part Henry VI, Part Butchery in Henry VI, Part and the emergence of Richard III Torture, rape, and cannibalism: Titus Andronicus . Plays and movies: Richard III and Romeo and Juliet Richard III for a violent era Romeo and Juliet . Shakespeare on war: King John to Henry V Muddled patriotism in King John Model warriors and model rulers in Henry IV Henry V and the idea of a just war . -

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

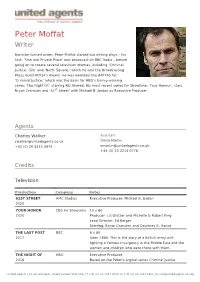

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

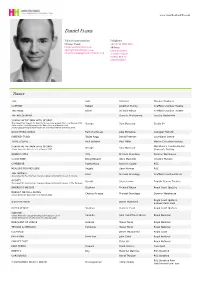

Daniel Evans

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Daniel Evans Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer COMPANY Robert Jonathan Munby Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE PRIDE Oliver Richard Wilson Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE ART OF NEWS Dominic Muldowney London Sinfonietta SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Tony Award Nomination for Best Performance by a Lead Actor in a Musical 2008 George Sam Buntrock Studio 54 Outer Critics' Circle Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical 2008 Drama League Awards Nomination for Distinguished Performance 2008 GOOD THING GOING Part of a Revue Julia McKenzie Cadogan Hall Ltd SWEENEY TODD Tobias Ragg David Freeman Southbank Centre TOTAL ECLIPSE Paul Verlaine Paul Miller Menier Chocolate Factory SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Wyndham's Theatre/Menier George Sam Buntrock Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical 2007 Chocolate Factory GRAND HOTEL Otto Michael Grandage Donmar Warehouse CLOUD NINE Betty/Edward Anna Mackmin Crucible Theatre CYMBELINE Posthumous Dominic Cooke RSC MEASURE FOR MEASURE Angelo Sean Holmes RSC THE TEMPEST Ariel Michael Grandage Sheffield Crucible/Old Vic Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in Ghosts) GHOSTS Osvald Steve Unwin English Touring Theatre Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in The Tempest) WHERE DO WE LIVE Stephen Richard -

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time Embarks on a Third Uk and Ireland Tour This Autumn

3 March 2020 THE NATIONAL THEATRE’S INTERNATIONALLY-ACCLAIMED PRODUCTION OF THE CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME EMBARKS ON A THIRD UK AND IRELAND TOUR THIS AUTUMN • TOUR INCLUDES A LIMITED SEVEN WEEK RUN AT THE TROUBADOUR WEMBLEY PARK THEATRE FROM WEDNESDAY 18 NOVEMBER 2020 Back by popular demand, the Olivier and Tony Award®-winning production of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time will tour the UK and Ireland this Autumn. Launching at The Lowry, Salford, Curious Incident will then go on to visit to Sunderland, Bristol, Birmingham, Plymouth, Southampton, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Dublin, Belfast, Nottingham and Oxford, with further venues to be announced. Curious Incident will also play for a limited run in London at Troubadour Wembley Park Theatre in Brent - London Borough of Culture 2020 - following the acclaimed run of War Horse in 2019. Curious Incident has been seen by more than five million people worldwide, including two UK tours, two West End runs, a Broadway transfer, tours to the Netherlands, Canada, Hong Kong, Singapore, China, Australia and 30 cities across the USA. Curious Incident is the winner of seven Olivier Awards including Best New Play, Best Director, Best Design, Best Lighting Design and Best Sound Design. Following its New York premiere in September 2014, it became the longest-running play on Broadway in over a decade, winning five Tony Awards® including Best Play, six Drama Desk Awards including Outstanding Play, five Outer Critics Circle Awards including Outstanding New Broadway Play and the Drama League Award for Outstanding Production of a Broadway or Off Broadway Play. -

March 2016 Conversation

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD IN COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE WNDC IN WASHINGTON THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION DIANA OWEN ♦ Tuesday, February 23 As we commemorate SHAKESPEARE 400, a global celebration of the poet’s life and legacy, the GUILD is delighted to co-host a WOMAN’S NATIONAL DEMOCRATIC CLUB gathering with DIANA OWEN, who heads the SHAKESPEARE BIRTHPLACE TRUST in Stratford-upon-Avon. The TRUST presides over such treasures as Mary Arden’s House, WITTEMORE HOUSE Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, and the home in which the play- 1526 New Hampshire Avenue wright was born. It also preserves the site of New Place, the Washington mansion Shakespeare purchased in 1597, and in all prob- LUNCH 12:30. PROGRAM 1:00 ability the setting in which he died in 1616. A later owner Luncheon & Program, $30 demolished it, but the TRUST is now unearthing the struc- Program Only , $10 ture’s foundations and adding a new museum to the beautiful garden that has long delighted visitors. As she describes this exciting project, Ms. Owen will also talk about dozens of anniversary festivities, among them an April 23 BBC gala that will feature such stars as Dame Judi Dench and Sir Ian McKellen. PEGGY O’BRIEN ♦ Wednesday, February 24 Shifting to the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY, an American institution that is marking SHAKESPEARE 400 with a national tour of First Folios, we’re pleased to welcome PEGGY O’BRIEN, who established the Library’s globally acclaimed outreach initiatives to teachers and NATIONAL ARTS CLUB students in the 1980s and published a widely circulated 15 Gramercy Park South Shakespeare Set Free series with Simon and Schuster. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

MORRISON Niamh

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd NIAMH MORRISON - Make-Up and Hair Designer FEATURES: THE COURIER Director: Zackary Adler. Producers: James Edward Barker, Marc Goldberg, David Haring and Andrew Prendergast. Starring: Olga Kurylenko, Gary Oldman and Dermot Mulroney. Rollercoaster Angel Productions/Capstone Group. THE DARK OUTSIDE Director: William McGregor. Producer: Hilary Bevan Jones. Starring: Maxine Peake, Richard Harrington, Mark Lewis Jones. Endor Productions. THE INFORMER Director: Andrea Di Stefano. Producers: Wayne Marc Godfrey, James Harris, Basil Iwanyk, Robert Jones Mark Lane and Ollie Madden. Starring: Joel Kinnaman, Rosamund Pike, Common and Clive Owen. Thunder Road Pictures. HEIDI: QUEEN OF THE MOUNTAINS Director: Bhavna Talwar. Producers: Sheetal Talwar and Simon Wright. Starring: Olivia Grant, Bill Nighy, Helen Baxendale and Mark Williams. WSG Film. FILTH Director: Jon S. Baird. Producers: Jon S. Baird, Will Clarke, Ken Marshall, Jens Meurer, Celine Rattray and Trudie Styler. Starring: James McAvoy, Imogen Poots, Jamie Bell, Eddie Marsden and Jim Broadbent. Steel Mill Pictures. OUTPOST II: BLACK SUN Director: Steve Barker. Producer: Kieran Parker. Starring: Catherine Steadman, Ali Craig and Nick Nevern. Black Camel Pictures. Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 NIAMH MORRISON Contd … 2 GUINEA PIGS Director: Ian Clark. Producers: Megan Stewart Wallace and Mat Wakeham, Starring: Aneurin Barnard, Alex Reid, Chris Larkin and Steve Evets. Incendiary Pictures. LEGACY Director: Thomas Ikimi. Producers: Arabella Page Croft and Kieran Parker. Starring: Idris Elba, William Hope, Monique Gabriela Curnen and Richard Brake. Black Camel Pictures. OUTCAST Director: Colm McCarthy.