Download PDF (98.7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Threshold of the Holocaust: Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms In

Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. of the Holocaust carried out by the local population. Who took part in these excesses, and what was their attitude towards the Germans? The Author Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms Were they guided or spontaneous? What Tomasz Szarota is Professor at the Insti- part did the Germans play in these events tute of History of the Polish Academy in Occupied Europe and how did they manipulate them for of Sciences and serves on the Advisory their own benefit? Delving into the source Board of the Museum of the Second Warsaw – Paris – The Hague – material for Warsaw, Paris, The Hague, World War in Gda´nsk. His special interest Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Kaunas, this comprises WWII, Nazi-occupied Poland, Amsterdam – Antwerp – Kaunas study is the first to take a comparative the resistance movement, and life in look at these questions. Looking closely Warsaw and other European cities under at events many would like to forget, the the German occupation. On the the Threshold of Holocaust ISBN 978-3-631-64048-7 GEP 11_264048_Szarota_AK_A5HC PLE edition new.indd 1 31.08.15 10:52 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. -

Theresienstadt Concentration Camp from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Theresienstadt concentration camp From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E "Theresienstadt" redirects here. For the town, see Terezín. Navigation Theresienstadt concentration camp, also referred to as Theresienstadt Ghetto,[1][2] Main page [3] was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress and garrison city of Contents Terezín (German name Theresienstadt), located in what is now the Czech Republic. Featured content During World War II it served as a Nazi concentration camp staffed by German Nazi Current events guards. Random article Tens of thousands of people died there, some killed outright and others dying from Donate to Wikipedia malnutrition and disease. More than 150,000 other persons (including tens of thousands of children) were held there for months or years, before being sent by rail Interaction transports to their deaths at Treblinka and Auschwitz extermination camps in occupied [4] Help Poland, as well as to smaller camps elsewhere. About Wikipedia Contents Community portal Recent changes 1 History The Small Fortress (2005) Contact Wikipedia 2 Main fortress 3 Command and control authority 4 Internal organization Toolbox 5 Industrial labor What links here 6 Western European Jews arrive at camp Related changes 7 Improvements made by inmates Upload file 8 Unequal treatment of prisoners Special pages 9 Final months at the camp in 1945 Permanent link 10 Postwar Location of the concentration camp in 11 Cultural activities and -

The Czechoslovak Exiles and Anti-Semitism in Occupied Europe During the Second World War

WALKING ON EGG-SHELLS: THE CZECHOSLOVAK EXILES AND ANTI-SEMITISM IN OCCUPIED EUROPE DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR JAN LÁNÍČEK In late June 1942, at the peak of the deportations of the Czech and Slovak Jews from the Protectorate and Slovakia to ghettos and death camps, Josef Kodíček addressed the issue of Nazi anti-Semitism over the air waves of the Czechoslovak BBC Service in London: “It is obvious that Nazi anti-Semitism which originally was only a coldly calculated weapon of agitation, has in the course of time become complete madness, an attempt to throw the guilt for all the unhappiness into which Hitler has led the world on to someone visible and powerless.”2 Wartime BBC broadcasts from Britain to occupied Europe should not be viewed as normal radio speeches commenting on events of the war.3 The radio waves were one of the “other” weapons of the war — a tactical propaganda weapon to support the ideology and politics of each side in the conflict, with the intention of influencing the population living under Nazi rule as well as in the Allied countries. Nazi anti-Jewish policies were an inseparable part of that conflict because the destruction of European Jewry was one of the main objectives of the Nazi political and military campaign.4 This, however, does not mean that the Allies ascribed the same importance to the persecution of Jews as did the Nazis and thus the BBC’s broadcasting of information about the massacres needs to be seen in relation to the propaganda aims of the 1 This article was written as part of the grant project GAČR 13–15989P “The Czechs, Slovaks and Jews: Together but Apart, 1938–1989.” An earlier version of this article was published as Jan Láníček, “The Czechoslovak Service of the BBC and the Jews during World War II,” in Yad Vashem Studies, Vol. -

Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938–1948

21 Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938 –1948 LUCIE ZADRAILOVÁ AND MILAN PECH 332 Lucie Zadražilová and Milan Pech Lucie Zadražilová (Skřivánková) is a curator at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, while Milan Pech is a researcher at the Institute of Christian Art at Charles University in Prague. Teir text is a detailed archival study of the activities of two Czech art institutions, the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague and the Mánes Association of Fine Artists, during the Nazi Protectorate era and its immediate aftermath. Te larger aim is to reveal that Czech cultural life was hardly dormant during the Protectorate, and to trace how Czech institutions negotiated the limitations, dangers, and interferences presented by the occupation. Te Museum of Decorative Arts cautiously continued its independent activities and provided otherwise unattainable artistic information by keeping its library open. Te Mánes Association of Fine Artists trod a similarly-careful path of independence, managing to avoid hosting exhibitions by representatives of Fascism and surreptitiously presenting modern art under the cover of traditionally- themed exhibitions. Tis essay frst appeared in the collection Konec avantgardy? Od Mnichovské dohody ke komunistickému převratu (End of the Avant-Garde? From the Munich Agreement to the Communist Takeover) in 2011.1 (JO) Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938–1948 In the light of new information gained from archival sources and contemporaneous documents it is becoming ever clearer that the years of the Protectorate were far from a time of cultural vacuum. Credit for this is due to, among other things, the endeavours of many people to maintain at least a partial continuity in public services and to achieve as much as possible within the framework of the rules set by the Nazi occupiers. -

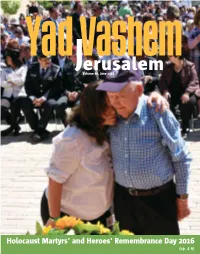

Jerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016 Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day 2016 (pp. 4-9) Yad VaJerusalemhem Contents Volume 80, Sivan 5776, June 2016 Inauguration of the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union ■ 2-3 Published by: Highlights of Holocaust Remembrance Day 2016 ■ 4-5 Students Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day Through Song, Film and Creativity ■ 6-7 Leah Goldstein ■ Remembrance Day Programs for Israel’s Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Security Forces ■ 7 Vice Chairmen of the Council: ■ On 9 May 2016, Yad Vashem inaugurated Dr. Yitzhak Arad Torchlighters 2016 ■ 8-9 Dr. Moshe Kantor the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on ■ 9 Prof. Elie Wiesel “Whoever Saves One Life…” the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, under the Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev Education ■ 10-13 auspices of its world-renowned International Director General: Dorit Novak Asper International Holocaust Institute for Holocaust Research. Head of the International Institute for Holocaust Studies Program Forges Ahead ■ 10-11 The Center was endowed by Michael and Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Laura Mirilashvili in memory of Michael’s News from the Virtual School ■ 10 for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman father Moshe z"l. Alongside Michael and Laura Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Furthering Holocaust Education in Germany ■ 11 Miriliashvili and their family, honored guests Academic Advisor: Graduate Spotlight ■ 12 at the dedication ceremony included Yuli (Yoel) Prof. Yehuda Bauer Imogen Dalziel, UK Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset; Zeev Elkin, Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Minister of Immigration and Absorption and Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Michal Cohen, “Beyond the Seen” ■ 12 Matityahu Drobles, Abraham Duvdevani, New Multilingual Poster Kit Minister of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage; Avner Prof. -

Poland and the Holocaust – Facts and Myths

The Good Name Redoubt The Polish League Against Defamation Poland and the Holocaust – facts and myths Summary 1. Poland was the first and one of the major victims of World War II. 2. The extermination camps, in which several million people were murdered, were not Polish. These were German camps in Poland occupied by Nazi Germany. The term “Polish death camps” is contradictory to historical facts and grossly unfair to Poland as a victim of Nazi Germany. 3. The Poles were the first to alert European and American leaders about the Holocaust. 4. Poland never collaborated with Nazi Germany. The largest resistance movement in occupied Europe was created in Poland. Moreover, in occupied Europe, Poland was one of the few countries where the Germans introduced and exercised the death penalty for helping Jews. 5. Hundreds of thousands of Poles – at the risk of their own lives – helped Jews survive the war and the Holocaust. Poles make up the largest group among the Righteous Among the Nations, i.e. citizens of various countries who saved Jews during the Holocaust. 6. As was the case in other countries during the war, there were cases of disgraceful behaviour towards Jews in occupied Poland, but this was a small minority compared to the Polish society as a whole. At the same time, there were also instances of disgraceful behaviour by Jews in relation to other Jews and to Poles. 7. During the war, pogroms of the Jewish people were observed in various European cities and were often inspired by Nazi Germans. Along with the Jews, Polish people, notably the intelligentsia and the political, socio-economic and cultural elites, were murdered on a massive scale by the Nazis and by the Soviets. -

Buddhism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search

Buddhism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A statue of Gautama Buddha in Bodhgaya, India. Bodhgaya is traditionally considered the place of his awakening[1] Part of a series on Buddhism Outline · Portal History Timeline · Councils Gautama Buddha Disciples Later Buddhists Dharma or Concepts Four Noble Truths Dependent Origination Impermanence Suffering · Middle Way Non-self · Emptiness Five Aggregates Karma · Rebirth Samsara · Cosmology Practices Three Jewels Precepts · Perfections Meditation · Wisdom Noble Eightfold Path Wings to Awakening Monasticism · Laity Nirvāṇa Four Stages · Arhat Buddha · Bodhisattva Schools · Canons Theravāda · Pali Mahāyāna · Chinese Vajrayāna · Tibetan Countries and Regions Related topics Comparative studies Cultural elements Criticism v • d • e Buddhism (Pali/Sanskrit: बौद धमर Buddh Dharma) is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha (Pāli/Sanskrit "the awakened one"). The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE.[2] He is recognized by adherents as an awakened teacher who shared his insights to help sentient beings end suffering (or dukkha), achieve nirvana, and escape what is seen as a cycle of suffering and rebirth. Two major branches of Buddhism are recognized: Theravada ("The School of the Elders") and Mahayana ("The Great Vehicle"). Theravada—the oldest surviving branch—has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and Mahayana is found throughout East Asia and includes the traditions of Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, Tendai and Shinnyo-en. In some classifications Vajrayana, a subcategory of Mahayana, is recognized as a third branch. -

European Jewish Digest: Looking at the Headlines Across Jewish Europe

EUROPEAN JEWISH DIGEST: LOOKING AT THE HEADLINES ACROSS JEWISH EUROPE VOLUME 2, ISSUE 6: JUNE 2015 1 / ISSUES CONCERNING ANTISEMITISM Violence, Vandalism & Abuse Instances of antisemitic vandalism and abuse occurred again in Greece in June. The disputed Holocaust memorial in Kevala (as reported in the May digest) was finally dedicated after the mayor agreed that no changes to the memorial were needed and it would be kept in its original location. However in his speech at the dedication, Panagiotis Sgouridis, deputy minister of rural development, was accused of abusing the memory of the Holocaust when he said that atrocities continue today including “the continuation of the extermination of the Assyrians by the jihadists, the invasion and occupation in northern Cyprus, the Kurdish issue, the blockade of Gaza, the genocidal dismemberment of Yugoslavia.” He added that monuments like this one was needed “because unfortunately many times the roles switch and the victims become bullies.” The memorial itself was then desecrated two weeks after its dedication, being covered in blue paint. In Athens, a memorial to the 13,000 Greek Jewish children murdered in the Holocaust was also desecrated with a Nazi swastika and SS insignia. The memorial is located next to a playground built in the children’s memory. In the UK, two Jewish men were allegedly racially abused and violently threatened. Whilst walking along the River Lea towpath in Hackney in London, a man approached the visibly looking Jewish males and allegedly shouted “f***ing Jews” before walking right up to the victims, saying “I’ll f***ing kill you” and “I’ll f***ing break your neck”. -

The Litvaks of Slobodka

IT’S THE LITVAKS KAUNASTIC OF SLOBODKA THE PEOPLE Danielius Pomerancas 17 ABRAHAM MAPU 21 DANIELEphraim POMERANZ Oshry (1808-1867) (1904–1981) AND MOISHE Abraham Mapu, born in Slobodka, Kaunas, is HOFMEKLER (1898–1965) considered the first Hebrew novelist. It’s probably true that he wrote his novels about life in ancient The two musicians were the leaders of the hottest Israel in a gazebo on the Aleksotas hill, making the orchestras of the interwar Kaunas. Both of them district a popular yet romantic getaway destina- were imprisoned in Kaunas ghetto, where, together tion for later generations of Jews in Kaunas. The with a few dozen of likeminded artists, they es- books of Mapu library on Ožeškienės g., established tablished an orchestra. The daughter of Pomeranz in 1908, were lost during the Holocaust. The Mapu was saved from the Ghetto by the family of Kip- street in the Old Town received its name in 1919 – it ras Petrauskas, the famous interwar opera singer Medžiai was changed during the Soviet occupation, but the and only reunited with her family decades later. correct version was implemented again in 1989. Both Pomeranz and Hofmekler were transferred to What’s today a youth literature and music library Dachau and both continued their musician careers on A. Mapu g. 18 was built as a Jewish community after the war. Pomeranz finally emigrated to Cana- canteen at the beginning of the 20th century and da, and Hofmekler settled in Munich, Germany. later used as headquarters for theEPHRAIM Jewish Inde- OSHRY pendence Fighters Union and the editorial office of “Apžvalga” newspaper. -

The Dc-Nazilication Law of 5Th March, 1946, However, Passed for Bavaria

202 PUNISHMENT OF CRIMINALS “ The Dc-Nazilication Law of 5th March, 1946, however, passed for Bavaria, Greatcr-Hcsse and Wurttcmbcrg-Badcn, provides definite sentences lor punishment in each type of olfencc. The Tribunal recommends that in no case should punishment imposed under Law No. 10 upon any members of an organisation or group declared by the Tribunal to be criminal exceed the punishment lixed by the D enazifica tion Law.(') The Dc-Nazilication Law of 5th March, 1946, referred to by the Tribunal, was in force in the United States Zone and, as far as restriction of personal liberty is concerned, its heaviest penalty did not exceed 10 years’ imprison ment. There were also provisions for confiscation of property and depriva tion of civil rights. As a study of the sentences passed by the United States Military Tribunal in Nuremberg for the crime of membership shows, these Tribunals have in fact followed the recommendation of the International Military Tribunal.^2) It may be also pointed out that for committing crimcs against humanity (a category more recently evolved and recognised as olfcnces than war crimcs), the accused Rothaug, who had been found guilty of no other types of crimcs, was sentenced by the Military Tribunal which conducted the Justicc Trial not to death but to life imprisonment, although many of his victims had suffered dcath.l3) On the other hand the International Military Tribunal sentenced to death Julius Strcichcr after finding him guilty on the one count of crimcs against humanity, which however involved many deaths.(4) It is thought that an interesting study could be made of the different types and degrees of severity of penalties passed on persons found guilty of different ofTcnccs under international law by Courts acting within the limits laid down by that law as to the punishment of criminals. -

Key Findings Many European Union Governments Are Rehabilitating World War II Collaborators and War Criminals While Minimisin

This first-ever report rating individual European Union countries on how they face up their Holocaust pasts was published on January 25, 2019 to coincide with UN Holocaust Remembrance Day. Researchers from Yale and Grinnell Colleges travelled throughout Europe to conduct the research. Representatives from the European Union of Progressive Judaism (EUPJ) have endorsed their work. Key Findings ● Many European Union governments are rehabilitating World War II collaborators and war criminals while minimising their own guilt in the attempted extermination of Jews. ● Revisionism is worst in new Central European members - Poland, Hungary, Croatia and Lithuania. ● But not all Central Europeans are moving in the wrong direction: two exemplary countries living up to their tragic histories are the Czech Republic and Romania. The Romanian model of appointing an independent commission to study the Holocaust should be duplicated. ● West European countries are not free from infection - Italy, in particular, needs to improve. ● In the west, Austria has made a remarkable turn-around while France stands out for its progress in accepting responsibility for the Vichy collaborationist government. ● Instead of protesting revisionist excesses, Israel supports many of the nationalist and revisionist governments. By William Echikson As the world marks the United Nations Holocaust Remembrance Day on January 27, European governments are rehabilitating World War II collaborators and war criminals while minimising their own guilt in the attempted extermination of Jews. This Holocaust Remembrance Project finds that Hungary, Poland, Croatia, and the Baltics are the worst offenders. Driven by feelings of victimhood and fears of accepting refugees, and often run by nationalist autocratic governments, these countries have received red cards for revisionism. -

Nazi Party from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Nazi Party From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the German Nazi Party that existed from 1920–1945. For the ideology, see Nazism. For other Nazi Parties, see Nazi Navigation Party (disambiguation). Main page The National Socialist German Workers' Party (German: Contents National Socialist German Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (help·info), abbreviated NSDAP), commonly known Featured content Workers' Party in English as the Nazi Party, was a political party in Germany between 1920 and 1945. Its Current events Nationalsozialistische Deutsche predecessor, the German Workers' Party (DAP), existed from 1919 to 1920. The term Nazi is Random article Arbeiterpartei German and stems from Nationalsozialist,[6] due to the pronunciation of Latin -tion- as -tsion- in Donate to Wikipedia German (rather than -shon- as it is in English), with German Z being pronounced as 'ts'. Interaction Help About Wikipedia Community portal Recent changes Leader Karl Harrer Contact page 1919–1920 Anton Drexler 1920–1921 Toolbox Adolf Hitler What links here 1921–1945 Related changes Martin Bormann 1945 Upload file Special pages Founded 1920 Permanent link Dissolved 1945 Page information Preceded by German Workers' Party (DAP) Data item Succeeded by None (banned) Cite this page Ideologies continued with neo-Nazism Print/export Headquarters Munich, Germany[1] Newspaper Völkischer Beobachter Create a book Youth wing Hitler Youth Download as PDF Paramilitary Sturmabteilung