Evaluating Employment and Community Opportunities Presented

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexandra Urban Renewal:- the All-Embracing Township Rejuvenation Programme

ALEXANDRA URBAN RENEWAL:- THE ALL-EMBRACING TOWNSHIP REJUVENATION PROGRAMME 1. Introduction and Background About the Alexandra Township The township of Alexandra is one of the densely populated black communities of South Africa reach in township culture embracing cultural diversity. This township is located about 12km (about 7.5 miles) north-east of the Johannesburg city centre and 3km (less than 2 miles) from up market suburbs of Kelvin, Wendywood and Sandton, the financial heart of Johannesburg. It borders the industrial areas of Wynberg, and is very close to the Limbro Business Park, where large parts of the city’s high-tech and service sector are based. It is also very near to Bruma Commercial Park and one of the hype shopping centres of Eastgate Shopping Centre. This township amongst the others has been the first stops for rural blacks entering the city in search for jobs, and being neighbours with the semi-industrial suburbs of Kew and Wynberg. Some 170 000 (2001 Census: 166 968) people live in this community, in an area of approximately two square kilometres. Alexandra extends over an area of 800 hectares (or 7.6 square kilometres) and it is divided by the Jukskei River. Two of the main feeder roads into Johannesburg, N3 and M1 pass through Alexandra. However, the opportunity to link Alexandra with commercial and industrial areas for some time has been low. Socially, Alexandra can be subdivided into three parts, with striking differences; Old Alexandra (west of the Jukskei River) being the poorest and most densely populated area, where housing is mainly in informal dwellings and hostels. -

A Case Study of Urban Renewal for the Presidential 10 Year Review Project

Alexandra: A Case study of urban renewal for the Presidential 10 year review project June 2003 Review by the Human Sciences Research Council (Democracy and Governance Programme) In association with Indlovo Link Dr. Marlene Roefs, Democracy and Governance, HSRC Mr. Vino Naidoo, Democracy and Governance, HSRC Mr. Mike Meyer, Indlovo Link Ms. Joan Makalela, Democracy and Governance, HSRC (Photography by Jankie Matlala) Our sincere appreciation goes to the City of Johannesburg (Region 7 Office), including the People’s Centre Information Services; the Social, Physical and LED Clusters of the ARP; and members of the public. TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ...............................................................................................................................3 1. Introduction...................................................................................................................................9 1.1 Urban Renewal Programme .........................................................................................10 1.2 Description of Alexandra.................................................................................................13 1.3 Population profile .............................................................................................................15 1.4 Overview of Recent History............................................................................................16 2. Development Planning Objectives.......................................................................................20 -

Department of Human Settlements Government Gazette No

Reproduced by Data Dynamics in terms of Government Printers' Copyright Authority No. 9595 dated 24 September 1993 671 NO. 671 NO. Priority Housing Development Areas Department of Human Settlements Housing Act (107/1997): Proposed Priority Housing Development Areas HousingDevelopment Priority Proposed (107/1997): Act Government Gazette No.. I, NC Mfeketo, Minister of Human Settlements herewith gives notice of the proposed Priority Housing Development Areas (PHDAs) in terms of Section 7 (3) of the Housing Development Agency Act, 2008 [No. 23 of 2008] read with section 3.2 (f-g) of the Housing Act (No 107 of 1997). 1. The PHDAs are intended to advance Human Settlements Spatial Transformation and Consolidation by ensuring that the delivery of housing is used to restructure and revitalise towns and cities, strengthen the livelihood prospects of households and overcome apartheid This gazette isalsoavailable freeonlineat spatial patterns by fostering integrated urban forms. 2. The PHDAs is underpinned by the principles of the National Development Plan (NDP) and allied objectives of the IUDF which includes: DEPARTMENT OFHUMANSETTLEMENTS DEPARTMENT 2.1. Spatial justice: reversing segregated development and creation of poverty pockets in the peripheral areas, to integrate previously excluded groups, resuscitate declining areas; 2.2. Spatial Efficiency: consolidating spaces and promoting densification, efficient commuting patterns; STAATSKOERANT, 2.3. Access to Connectivity, Economic and Social Infrastructure: Intended to ensure the attainment of basic services, job opportunities, transport networks, education, recreation, health and welfare etc. to facilitate and catalyse increased investment and productivity; 2.4. Access to Adequate Accommodation: Emphasis is on provision of affordable and fiscally sustainable shelter in areas of high needs; and Departement van DepartmentNedersettings, of/Menslike Human Settlements, 2.5. -

All Shi, Non-Compliant Shi, Public & Housing Institutions

STAATSKOERANT, 8 NOVEMBER 2013 No. 36996 67 GENERAL NOTICES ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS NOTICE 1088 OF 2013 a PCA Social Housing Regulatory Authority LEGAL NOTICE 01/2013 ATTENTION: ALL SHIP NON-COMPLIANT SHI, THE PUBLIC & HOUSING INSTITU ilOrS The Social Housing Regulatory Authority ("Regulatory Authority" or "SHRA") is the regulator of social housing in the Republic. The Regulatory Authority derives its mandate from the Social Housing Act 16 of 2008 ("the Act" or "this Act") and the Social Housing Regulations ("Regulations"). The mandate of the Regulatory Authority is to invest in projects in the social housing sector ("the sector") and regulate all projects in the sector which were funded with institutional subsidies and/or the capital grant (herewith collectively referred to as public funds). In terms of regulation 4, chapter 2; "(1) The Regulatory Authority may request a previously provisionally accredited social housing institution contemplated in section 13(1) of the Act to submit to the Regulatory Authority any such information and documentation regarding housing developments developed or administered by the institution as may be prescribed by rules of the Regulatory Authority. (2) A previously provisionally accredited social housing institution contemplated above, must apply in the manner and format" referred to in regulation 2 for accreditation as a social housing institution." As such, all institutions that undertook housing development before the coming into operation of the Social Housing Act 16 of 2008, must kindly take note in terms of section 13(1) and (2); "(1) allinstitutions having undertaken housing developments with the benefit of an institutional subsidy are provisionally accredited SHI for purposes of the Act, subject to the provisions of this Act and the powers of the Regulatory Authority. -

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region E

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION E No. Councillors Party: Region: Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & No: Contact Details: 1. Cllr. Bongani Nkomo DA E 32 Limbro Park, Modderfontein, Katlego More 011 582 -1606/1589 Greenstone, Longmeadow, 083 445 1468 073 552 0680 Juskei View, Buccleuch, [email protected] Sebenza, Klipfontein 2. Cllr. Lionel Mervin Greenberg DA E 72 Dunhill, Fairmount ,Fairmount Mpho Sepeng 082 491 6070 Ridge EXT 1,2 Fairvale, 011 582 1585 [email protected] Fairvale EXT 1, Glenkay, 082 418 5145 Glensan, Linksfield EXTs 1, 2, [email protected] 3, 4, 5, Linksfield North, Linksfield Ridge EXT 1, Sandringham, Silvamonte EXT1,Talbolton, Sunningdale, Sunningdale Ext 1,2,3,4,5, 7,8,11,12,Sunningdale Percelia, Percelia Estate, Percelia Ext, Sydenham, Glenhazel, and Orange Grove North of 14th Street,Viewcrest 3. Cllr. Eleanor Huggett DA E 73 Bellevue, Fellside, Houghton Teboho Maapea 071 785 8068 Estate, Mountain View, 079 196 5019 [email protected] Norwood, Oaklands, Orchards, [email protected] Parkwood EXT1, Riviera, Saxonwold EXTs1, 2,3,4, Victoria EXT2 Killarney 4. Cllr. David Ross Fisher DA E 74 Wanderers, Waverley, Mpho Sepeng 011 582-1609 Bagleyston, Birdhaven, Birnam, 011 582 1585 082 822 6070 Bramley Gardens, Cheltondale, 082 418 5145 [email protected] Chetondale EXT1, 2, 3, Elton [email protected] Hill EXTs 1, 2, 3, 4, Fairway, Fairwood, Forbesdale, Green World,Glenhazel EXTs 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14 Gresswold, Hawkins Estate, Hawkins Estate EXT1, Highlands North EXT2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, Highlands North Extension,Illovo EXT 1,Kentview,Kew,Maryvale, Melrose,Melrose Estate,Melrose Ext 1,2, Melrose North Ext 1,2,3,4,57,8,Orange Grove,Orchards From Hamlen to African Street(Highroad border), 1,2,Raedene Estate, Raedene Estate Ext 1,Raumarais Park ,Rouxville, Savoy Estate, Ridge, 5. -

Alexandra Urban Renewal Project and Neighborhood Development

Alexandra Urban Renewal Project and Neighborhood development: An unanswered questions? By George Onatu & Aurobindo Ogra Department of Town and Regional Planning Faculty of Engineering & Built Environment University of Johannesburg PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS An Aerial View of Alex PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS INTRODUCTION Urban growth has been strongly associated with poverty and slum growth. According to UN-HABITAT report 2010/11 a number of countries have to some extent managed to curb the further expansion of slum and improved the living conditions of the citizens. Between 2000 and 2010, a total of 227 million people in developing world will have moved out of slum conditions. Governments have collectively exceeded the slum target of Millennium Development Goal 7 by at least 2.2 times, and 10 years ahead of agreed 2020 deadline. Asia stood at the forefront of successful effort to reach the slum target with governments in the region together improving the lives of 172 million slum dwellers between 2010 and 2011. This figure represents 74% of the total number of urban residents in the world. In Africa an estimated 24 million slum dwellers have improved in the last decade representing 12% of the global effort. North Africa (Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia) were the most successful. This are followed by Ghana, Senegal, Uganda, Rwanda and Guinea. How far have we fared in this regard? PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS Introduction continued….. In South Africa levels of unemployment and poverty are extremely high and remain two of South Africa’s most pressing problem. The level of unemployment was 9.18% in 1972, 7% in 1980, 10% in 1985, 15% in 1990, 22%in 1995 (Human Development Report, 2004 cited in Thwala, 2009:1), 30.2% in 2002, 27.4% in 2003, 25.6% in 2004, and 26.5% in 2005 (Labour Force Surveys (LFS), 2000-2005) and 24.5 ( StatSA, 2011). -

SAARF OHMS 2006 Database Layout

SAARF OUTDOOR MEASUREMENT SURVEY PRIVATE & CONFIDENTIAL Outdoor Database Layout South Africa (GAUTENG & KWAZULU-NATAL) August 2007 FILES FOR COMPUTER BUREAUX Prepared for: - South African Advertising Research Foundation (SAARF) Prepared by: - Nielsen Media Research and Nielsen Outdoor Copyright Reserved Confidential 1 The following document describes the content of the database files supplied to the computer bureaux. The database includes four input files necessary for the Outdoor Reach and Frequency algorithms: 1. Outdoor site locations file (2 – 3PPExtracts_Sites) 2. Respondent file (2 – 3PPExtracts_Respondents) 3. Board Exposures file (2 – Boards Exposure file) 4. Smoothed Board Impressions file (2 – Smoothed Board Impressions File) The data files are provided in a tab separated format, where all files are Window zipped. 1) Outdoor Site Locations File Format: The file contains the following data fields with the associated data types and formats: Data Field Max Data type Data definitions Extra Comments length (where necessary) Media Owner 20 character For SA only 3 owners: Clear Channel, Outdoor Network, Primedia Nielsen Outdoor 6 integer Up to a 6-digit unique identifier for Panel ID each panel Site type 20 character 14 types. (refer to last page for types) Site Size 10 character 30 size types (refer to last pages for sizes) Illumination hours 2 integer 12 (no external illumination) 24 (sun or artificially lit at all times) Direction facing 2 Character N, S, E, W, NE, NW, SE, SW Province 25 character 2 Provinces – Gauteng , Kwazulu- -

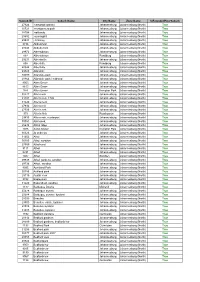

Netflorist Designated Area List.Pdf

Subrub ID Suburb Name City Name Zone Name IsExtendedHourSuburb 27924 carswald kyalami Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30721 montgomery park Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28704 oaklands Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28982 sunninghill Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29534 • bramley Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 8736 Abbotsford Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28048 Abbotts ford Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29972 Albertskroon Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 897 Albertskroon Randburg Johannesburg (North) True 29231 Albertsville Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 898 Albertville Randburg Johannesburg (North) True 28324 Albertville Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29828 Allandale Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30099 Allandale park Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28364 Allandale park / midrand Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 9053 Allen Grove Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 8613 Allen Grove Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 974 Allen Grove Kempton Park Johannesburg (North) True 30227 Allen neck Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 31191 Allen’s nek, 1709 Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 31224 Allens neck Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 27934 Allens nek Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 27935 Allen's nek Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 975 Allen's Nek Roodepoort Johannesburg (North) True 29435 Allens nek, rooderport Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30051 Allensnek, Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28638 -

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors by Region, Suburbs and Political Party

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS BY REGION, SUBURBS AND POLITICAL PARTY No. Councillor Name/Surname & Par Region: Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Cotact Details: ty: No: 1. Cllr. Msingathi Mazibukwana ANC G 1 Streford 5,6,7,8 and 9 Phase 1, Bongani Dlamini 078 248 0981 2 and 3 082 553 7672 011 850 1008 011 850 1097 [email protected] 2. Cllr. Dimakatso Jeanette Ramafikeng ANC G 2 Lakeside 1,2,3 and 5 Mzwanele Dloboyi 074 574 4774 Orange Farm Ext.1 part of 011 850 1071 011 850 116 083 406 9643 3. Cllr. Lucky Mbuso ANC G 3 Orange Farm Proper Ext 4, 6 Bongani Dlamini 082 550 4965 and 7 082 553 7672 011 850 1073 011 850 1097 4. Cllr. Simon Mlekeleli Motha ANC G 4 Orange Farm Ext 2,8 & 9 Mzwanele Dloboyi 082 550 4965 Drieziek 1 011 850 1071 011 850 1073 Drieziek Part 4 083 406 9643 [email protected] 5. Cllr. Penny Martha Mphole ANC G 5 Dreziek 1,2,3,5 and 6 Mzwanele Dloboyi 082 834 5352 Poortjie 011 850 1071 011 850 1068 Streford Ext 7 part 083 406 9643 [email protected] Stretford Ext 8 part Kapok Drieziek Proper 6. Shirley Nepfumbada ANC G 6 Kanama park (weilers farm) Bongani Dlamini 076 553 9543 Finetown block 1,2,3 and 5 082 553 7672 010 230 0068 Thulamntwana 011 850 1097 Mountain view 7. Danny Netnow DA G 7 Ennerdale 1,3,6,10,11,12,13 Mzwanele Dloboyi 011 211-0670 and 14 011 850 1071 078 665 5186 Mid – Ennerdale 083 406 9643 [email protected] Finetown Block 4 and 5 (part) Finetown East ( part) Finetown North Meriting 8. -

Proposed Priority Housing Development Areas 42464 L of All Well Needs; Segments Apartheid Previously

671 NO. 671 NO. Priority Housing Development Areas Department of Human Settlements Housing Act (107/1997): Proposed Priority Housing Development Areas HousingDevelopment Priority Proposed (107/1997): Act Government Gazette No.. I, NC Mfeketo, Minister of Human Settlements herewith gives notice of the proposed Priority Housing Development Areas (PHDAs) in terms of Section 7 (3) of the Housing Development Agency Act, 2008 [No. 23 of 2008] read with section 3.2 (f-g) of the Housing Act (No 107 of 1997). 1. The PHDAs are intended to advance Human Settlements Spatial Transformation and Consolidation by ensuring that the delivery of housing is used to restructure and revitalise towns and cities, strengthen the livelihood prospects of households and overcome apartheid This gazette isalsoavailable freeonlineat spatial patterns by fostering integrated urban forms. 2. The PHDAs is underpinned by the principles of the National Development Plan (NDP) and allied objectives of the IUDF which includes: DEPARTMENT OFHUMANSETTLEMENTS DEPARTMENT 2.1. Spatial justice: reversing segregated development and creation of poverty pockets in the peripheral areas, to integrate previously excluded groups, resuscitate declining areas; 2.2. Spatial Efficiency: consolidating spaces and promoting densification, efficient commuting patterns; STAATSKOERANT 2.3. Access to Connectivity, Economic and Social Infrastructure: Intended to ensure the attainment of basic services, job opportunities, transport networks, education, recreation, health and welfare etc. to facilitate and catalyse increased investment and productivity; 2.4. Access to Adequate Accommodation: Emphasis is on provision of affordable and fiscally sustainable shelter in areas of high needs; and Departement van Department Nedersettings, of/Menslike Human Settlements, 2.5. Provision of Quality Housing Options: Ensure that different housing typologies are delivered to attract different market segments at appropriate quality and innovation. -

List of 2 453 Informal Settlements Gathered by NDHS As at Nov 2017

List of 2 453 Informal Settlements gathered by NDHS as at Nov 2017 ANNEXURE A Num Province Local Municipality Settlement Name NUSP Structures Households 1 Eastern Cape Mbizana LM Downtown Mdakamfene B1 425 2 Eastern Cape Mbizana LM Highland Ext 4 A 872 3 Eastern Cape Ntabankulu LM Silvercity B2 58 4 Eastern Cape Umzimvubu LM Chithwa A 731 5 Eastern Cape Umzimvubu LM Silvercity B1 985 6 Eastern Cape Amahlati LM Bongolethu/Isidenge A 700 7 Eastern Cape Amahlati LM Cenyu A 450 8 Eastern Cape Amahlati LM Daliwe A 500 9 Eastern Cape Amahlati LM Katikati A 300 10 Eastern Cape Amahlati LM kubusi Greenfields A 304 11 Eastern Cape Amahlati LM Mlungisi A 350 12 Eastern Cape Amahlati LM Squashville A 467 13 Eastern Cape Amahlati LM Upper Izele B1 1238 14 Eastern Cape Great Kei LM Elusizini 43 15 Eastern Cape Great Kei LM Emagrangxeni 17 16 Eastern Cape Great Kei LM Eskolweni 17 17 Eastern Cape Great Kei LM Icwili 98 18 Eastern Cape Great Kei LM Komanishi 19 19 Eastern Cape Great Kei LM Makazi 80 20 Eastern Cape Great Kei LM Morgan Bay 143 21 Eastern Cape Mbhashe LM GPO A 150 22 Eastern Cape Mbhashe LM Kwa Agriculture C 100 23 Eastern Cape Mbhashe LM Town A 350 24 Eastern Cape Mbhashe LM Zone 14 C 250 25 Eastern Cape Mnquma LM Bhuhgeni A 400 26 Eastern Cape Mnquma LM Emabhaceni A 100 27 Eastern Cape Mnquma LM Madiba A 500 Page 1 of 85 List of 2 453 Informal Settlements gathered by NDHS as at Nov 2017 Num Province Local Municipality Settlement Name NUSP Structures Households 28 Eastern Cape Mnquma LM New Skiet A 240 29 Eastern Cape Mnquma LM Ou Skiet -

Preliminary Route Determination Report for Phase 1 of the GRRIN

PRELIMINARY ROUTE DETERMINATION REPORT – PHASE 01 OF THE GAUTRAIN RAPID RAIL INTEGRATED NETWORK EXTENSION FROM MARLBORO STATION TO LITTLE FALLS STATION PROJECT TITLE: PRELIMINARY ROUTE ALIGNMENT STUDY FOR RAPID RAIL INTEGRATED NETWORK EXTENSION Project No.: GMASRFQ0808024 Our Ref: J37057 Department: GMA Technical Date Issued: 28 June 2021 Preliminary Route Determination Report – Phase 01 of The Gautrain Rapid Rail Integrated Network Extension From Marlboro Station To Little Falls Station - June 2021 ii Table of Contents List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................... iv 1 Scope of Appointment .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Scope of Work ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.3 List of Drawings ...................................................................................................................... 2 2 Description of the Route ................................................................................................................. 3 2.1 Destinations