An Integrated Activity Course for Juniors. the Bell Educational Trust Academic Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inspiring English Courses for Young Learners (Aged 7-17) 2016

#mybellstory inspiring engLish coUrses FOR YOUNG LEARNERS (AGED 7-17) 2016 60 YEARS OF TEACHING EXPERTISE PIETRO LIDIA JU CHEN BIANCAMARIA MARIA SHEENA FARAH HILSAN WELcoME to BELL A place where learning is brought to life, the English language unlocks a world of opportunity and every student is supported to achieve their goals and dreams. Since our first school opened in 1955, we’ve created success stories for over a million students – read our student stories and join us to start writing your Bell story today. #mybellstory share your Bell story Bell Educational Trust is a A big thank you TIER 4 SPONSOR Thank you to all students who studied with us in 2015. A special thanks goes on the UKVI register of sponsors to those students and staff members who feature in this brochure. UNLOCK THE POWER WATCH OUR OF ENGLISH VIDEOS ONLINE BELLENGLISH.COM/ YOUR BELL STORY STARTS HERE VIDEOS THE BELL STORY OUR CENTRES OUR COURSES INCLUDE: SO FAR... BELL 06 TUITION, STUDY ST ALBANS MATERIALS AND COURSE PORTFOLIO 28 RESIDENTIAL ACCOMMODATION AND ALL MEALS BLOXHAM SCHOOL A FULL PROGRAMME OF SOCIAL ACTIVITIES OUTSTANDING EDUCATION • CAMBRIDGE 30 LEARNING THE BELL WAY A full programme StaNSTED 08 LUTON of STUDY TOURS THE LEYS, LONDON CAMBRIDGE YOUR CHILD’S EBBSFLEET OXFORD • COMPREHENSIVE LEARNING EXPERIENCE • HEatHROW 32 SUPERVISION BY QUALIFIED STAFF 10 WELLINGTON TRANSFERS FROM GATWICK AND TO DESIGNATED EXCEPTIONAL COLLEGE AIRPORTS ON SCHEDULED WELFARE AND 34 ARRIVAL AND SUPPORT DEPARTURE DAYS free internet 12 FACILITIES access ART ROOM COOKERY ROOM DRAMA STUDIO FREE LAUNDRY SERVICE DANCE STUDIO BELL BLOXHAM THE LEYS WELLINGTON THEATRE OUR COURSES ST ALBANS SCHOOL SCHOOL COLLEGE INDOOR SWIMMING POOL COMPREHENSIVE OUTDOOR SWIMMING POOL INSURANCE engLish EXPLORER 14 CLIMBING WALL winter EXPLORER 20 TENNIS COURTS ARCHERY RANGE INTERNATIONAL STUDY PREPARATION 22 OUTDOOR SPORTS FIELDS YOUNG BUSINESS LEADERS 24 ALL WEATHER SPORTS PITCHES (ASTRO TURF) INDOOR SPORTS HALL YOUNG CAMBRIDGE SCHOLARS 26 SQUASH COURTS 04 bellenglish.com bellenglish.com 05 THE STORY SO FAR.. -

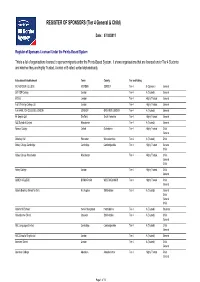

REGISTER of SPONSORS (Tier 4) Date: 09-February-2016

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tier 4) Date: 09-February-2016 Register of Licensed Sponsors This is a list of institutions licensed to sponsor migrants under Tier 4 of the points-based system. It shows the sponsor's name, their primary location, their sponsor type, the location of any additional centres being operated (including centres which have been recognised by the Home Office as being embedded colleges), the rating of their licence against each sub tier(s), the sub tier(s) they are licensed for, and whether the sponsor is subject to an action plan to help ensure immigration compliance. Legacy sponsors cannot sponsor any new students. For further information about Tier 4 of the points-based system, please refer to the Tier 4 Guidance for Sponsors on the GOV.UK website. No. of Sponsors Licensed under Tier 4: 1,399 Sponsor Name Town/City Sponsor Type Additional Status Sub Tier Immigration Locations Compliance Abacus College Oxford Independent school Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abberley Hall Worcester Independent school Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Independent school Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbey College in London London Independent school Probationary Tier 4 (Child) Sponsor Probationary Tier 4 General Sponsor Abbey College Manchester Manchester Independent school Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) ABBEY COLLEGE BIRMINGHAM Independent school Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbots Bromley -

ED312892.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 312 392 FL 018 215 AUTHOR Hopwood, Tony TITLE The Use of the Word-Processor in the Teachingof English as a Foreign Language to Adults. Academic Reports. INSTITUTION Bell Educational Trust, ("m'ridge (England). REPORT NO ISBN-1-870969-15-4 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 49p. AVAILABLE FROMDirector (Education), Bell Educational Trust, Hillscross, Red Cross Lane, Cambridge CB2 2QX, England. PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142)-- Guides - Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Students; Classroom Techniques; *Computer Assisted Instruction; *English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; Grammar; Reading Instruction; Second Language Instruction; Skill Development; Speech Skills; Surveys; *Teacher Attitudes; Vocabulary Development; *Word Processing;Writing Instruction ABSTRACT A discussion of the use of word processingfor the instruction of English as a Second Language (ESL)is presented in two parts. The first addresses the uses of thetechnology in teaching language skills, including writing, vocabulary,grammatical competence, reading skills, and oral skills. Relatedliterature is reviewed and specific examples of classroomtechniques are presented. The second part reports on a survey of teacherattitudes concerning the use of word processors. Results _uggestthat most teachers believe the word processor plays onlya minor role in the development of writing skills and are not clear aboutwhat that role is, beyond its motivational effect. It is concluded thatthe most widely acceptable forms of word processoruse in ESL are those that involve a central role for the teacher as a developer ofinstructional materials, guide, resource manager, andinformation and feedback source, and for the student as initiator, experimenter,and collaborator, the roles normally filled by teacherand student in a communicative classroom. -

20 Young Learners

20 English Language Courses Young learners #mybellstory Your story with Bell Courses Learning The Bell Way 4 Create your ideal course 12 Why study with Bell? 7 Effective English 15 The Bell Story 8 IELTS exam preparation 16 Cambridge Exam preparation 19 Study in Cambridge 26 Skills workshops 20 Bell Cambridge campus 28 Business skills 21 Study in London 30 1 to 1 tuition 22 Bell London campus 32 Language in Action 23 University Foundation Programme 25 Accommodation 34 Teacher training 38 Bell_English Bellenglishstudents Bell_English Bellinternational Courses for groups 40 BRITISH COUNCIL INSPECTION, BELL CAMBRIDGE, 2018 14 points of excellence Strategic and quality management Premises and facilities Learner management Staff management Learning resources Teaching Student administration Academic staff profile Care of students Publicity Academic management Accommodation June 2018 Course design Leisure opportunities. INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS INSPECTORATE, BELL CAMBRIDGE & LONDON, JUNE 2018 Rated ‘excellent’ in ISI report “Feedback to students is positive, “Students report that they are extremely well- Learning encouraging and accurate and clearly supported and would recommend the schools to identifies areas for improvement.” others.” The Bell Way “Teaching is excellent and results in high “Detailed planning and an extensive understanding levels of student progress. Teachers are of the needs of their students allow teachers to experienced, well-qualified and have successfully adapt lessons to meet individual An integrated approach excellent subject knowledge.” learning needs and effectively challenge students.” We deliver outstanding education and The Bell Way Bell welcomed students from our students benefit from over 60 years These six principles ensure that of educational expertise. We teach you are both challenged and 122 countries or territories in 2018 students as well as teachers from all supported. -

Alan Pulverness

Alan Pulverness Born London 23 October 1946. BA (Hons) 1st class in Comparative Literature and Applied Linguistics (1974)-University of East Anglia RSA/UCLES Cert (now Dip) TEFLA (1979/80) Teaching/Teacher Training since 1995: Freelance author/teacher trainer/ELT consultant; associate trainer, Norwich Institute for Language Education-courses in ELT methodology, literature and cultural studies in People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, Eastern/Central/Western Europe, Latin America and the UK. since 1996: Course Director, Advanced Certificate in TEFL: Masters Level Award joint programme: Norwich Institute for Language Education and the School of Education and Professional Development, University of East Anglia (from 2001 with Leeds Metropolitan University). 1974-1994: Teacher/Teacher Trainer, The Bell Educational Trust, Norwich-language improvement and methodology for teachers from China, Latin America, Middle East, North Africa, Western Europe. since 1974 - Cambridge/RSA Diploma in English Language Teaching to Adults; Course Tutor; Assessor (since 1994). - Cambridge/RSA Certificate in Teaching English as a Foreign Language to Adults-Course Tutor (since 1980); Assessor (since 1983). 1991-1992: Course Director: RSA distance learning Diploma in Teaching Foreign Languages to Adults-validated by The Institute for Applied Language Studies, University of Edinburgh. Consultancies 2005-2006: Hacettepe Universoty, Ankara, Turkey-syllabus design 2005 : University of East London-Distance MA materials design. 2004-2005: Oxford University Department for Continuing Education- Masters Level syllabus design. 2001: The British Council, Malta-Cultural Studies syllabus renewal. Voluntary Service Overseas, China-communicative methodology. 1999-2000: The British Council, Poland-British Cultural Studies materials development. 1997-2001: The British Council, Hungary-Cultural Studies materials development. -

HTS WEB Report Processor V2.1

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tier 4 General & Child) Date : 22/06/2011 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-Based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under the Points-Based System. It shows organisations that are licensed under Tier 4 Students and whether they are Highly Trusted, A-rated or B-rated, sorted alphabetically. Educational Establishment Town County Tier and Rating 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE MORDEN SURREY Tier 4 A (Trusted) General 360 GSP College London Tier 4 A (Trusted) General 4N ACADEMY LIMITED London Tier 4 B (Sponsor) General 5 E Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A & S Training College Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON LONDON GREATER LONDON Tier 4 A (Trusted) General A+ English Ltd Sheffield South Yorkshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A2Z School of English Manchester Tier 4 A (Trusted) General Abacus College Oxford Oxfordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abberley Hall Worcester Worcestershire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Cambridgeshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abbey College Manchester Manchester Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abbey College London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child ABBEY COLLEGE BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abbots Bromley School for Girls Nr. Rugeley Staffordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abbot's Hill School Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Students Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Staffordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child -

Tier 4 - Used - Period: 01/01/2012 to 31/12/2012

Tier 4 - Used - Period: 01/01/2012 to 31/12/2012 Organisation Name Total More House School Ltd 5 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE 65 360 GSP College 15 4N ACADEMY LIMITED † 5 E Ltd 10 A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON 20 A+ English Ltd 5 A2Z School of English 40 Abacus College 30 Abberley Hall † Abbey College 120 Abbey College Cambridge 140 Abbey College Manchester 55 Abbots Bromley School for Girls 15 Abbotsholme School 25 ABC School of English Ltd 5 Abercorn School 5 Aberdeen College † Aberdeen Skills & Enterprise Training 30 Aberystwyth University 520 ABI College 10 Abingdon School 20 ABT International College † Academy De London 190 Academy of Management Studies 35 ACCENT International Consortium for Academic Programs Abroad, Ltd. 45 Access College London 260 Access Skills Ltd † Access to Music 5 Ackworth School 50 ACS International Schools Limited 50 Active Learning, LONDON 5 Organisation Name Total ADAM SMITH COLLEGE 5 Adcote School Educational Trust Limited 20 Advanced Studies in England Ltd 35 AHA International 5 Albemarle Independent College 20 Albert College 10 Albion College 15 Alchemea Limited 10 Aldgate College London 35 Aldro School Educational Trust Limited 5 ALEXANDER COLLEGE 185 Alexanders International School 45 Alfred the Great College ltd 10 All Hallows Preparatory School † All Nations Christian College 10 Alleyn's School † Al-Maktoum College of Higher Education † ALPHA COLLEGE 285 Alpha Meridian College 170 Alpha Omega College 5 Alyssa School 50 American Institute for Foreign Study 100 American InterContinental University London Ltd 85 American University of the Caribbean 55 Amity University (in) London (a trading name of Global Education Ltd). -

English As an Additional Language: Proficiency in English, Educational Achievement and Rate of Progression in English Language Learning

UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION February 2020 English as an Additional Language: Proficiency in English, educational achievement and rate of progression in English language learning AUTHORS Professor Steve Strand Dr Ariel Lindorff ENGLISH AS AN ADDITIONAL LANGUAGE: PROFICIENCY IN ENGLISH, EDUCATIONAL ACHIEVEMENT AND RATE OF PROGRESSION IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNING Copyright All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner. Applications for the copyright owner’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher. Copyright © University of Oxford, Unbound Philanthropy, and The Bell Educational Trust Limited (operating as The Bell Foundation) The Bell Educational Trust Limited is a charitable company limited by guarantee number 1048465, established on 5 April 1972, and a charity registered with the Charity Commission number 311585 The Bell Foundation Hillscross Red Cross Lane Cambridge CB2 0QU www.bell-foundation.org.uk 2 Research Team Steve Strand is Professor of Education at the University Oxford, Department of Education. Steve Strand has been Professor of Education at the University of Oxford since January 2013. Previously he was Professor of Education at the University of Warwick (2005-2012). Prior to that Steve was Senior Assessment Consultant at GL Assessment, the UK’s leading educational test and assessment publisher (1998-2005) and Head of Research and Evaluation at Wandsworth and at Croydon Local Education Authorities (1988-1998). -

HTS WEB Report Processor V2.1

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tier 4 General & Child) Date : 07/02/2011 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-Based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under the Points-Based System. It shows organisations that are licensed under Tier 4 Students and whether they are Highly Trusted, A-rated or B-rated, sorted alphabetically. Educational Establishment Town County Tier and Rating 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE MORDEN SURREY Tier 4 B (Sponsor) General 360 GSP College London Tier 4 A (Trusted) General 5 E Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A & S Training College Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON LONDON GREATER LONDON Tier 4 A (Trusted) General A+ English Ltd Sheffield South Yorkshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A2Z School of English Manchester Tier 4 A (Trusted) General Abacus College Oxford Oxfordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abberley Hall Worcester Worcestershire Tier 4 A (Trusted) Child Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Cambridgeshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abbey College Manchester Manchester Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Child Abbey College London Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General ABBEY COLLEGE BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abbots Bromley School for Girls Nr. Rugeley Staffordshire Tier 4 A (Trusted) General Child General Child Abbot's Hill School Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire Tier 4 A (Trusted) Students Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Staffordshire Tier 4 A (Trusted) Child General ABC Languages Limited Cambridge -

Teacher Training & Development

2020 Teacher training & development Developing you and your team 1 • 2 Your story with Bell Teacher training courses What is your learning goal? 4 CELTA 20 • Why study with Bell? 6 Bell Teacher Academy courses 24 Teacher stories to inspire you 8 Delta 34 The Bell Story 10 Teacher development courses for groups 38 Courses for your class 40 Locations Bell Cambridge 17 Feel at home in the UK 36 Bell Teacher Academy 22 3 What is your learning goal? We offer courses across all stages of development to suit your learning needs and goals. Learn to teach Develop your English teaching practice CELTA Bell Teacher Academy Bell Cambridge Cambridge 6 January | 20 April | 1 June | 3 August From 28 June to 22 August Min. language level: Advanced C1 Various levels Take your first step to becoming a teacher. Bell Teacher Academy has a range of professional Our teacher trainees gain the practical development courses taught by experts in the skills, knowledge and qualification to get industry. Develop your teaching, learn new skills teaching jobs anywhere in the world. and be part of a global teaching community. For more information, see page 20 For more information, see page 22 4 INTRODUCTION TO BELL Become an Advanced Develop your Practitioner teachers DELTA Group programmes Cambridge / Online Cambridge / Your home country Multiple modules dates available Any time of year Min. language level: Proficient C1 / C2 Various levels Progress to senior roles with a Delta. The We can create a teacher training course Delta is the highest qualification for English perfectly matched to the needs of teachers language teachers. -

English As an Additional Language, Proficiency in English and Pupils' Educational Achievement

UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION OCTOBER 2018 English as an Additional Language, proficiency in English and pupils’ educational achievement: An analysis of Local Authority data AUTHORS Professor Steve Strand Annina Hessel ENGLISH AS AN ADDITIONAL LANGUAGE, PROFICIENCY IN ENGLISH AND PUPILS’ EDUCATIONAL ACHIEVEMENT: AN ANALYSIS OF LOCAL AUTHORITY DATA Copyright All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner. Applications for the copyright owner’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher. Copyright © University of Oxford, Unbound Philanthropy, and The Bell Educational Trust Limited (operating as The Bell Foundation) The Bell Educational Trust Limited is a charitable company limited by guarantee number 1048465, established on 5 April 1972, and a charity registered with the Charity Commission number 311585 The Bell Foundation Hillscross Red Cross Lane Cambridge CB2 0QU www.bell-foundation.org.uk 2 Research Team Steve Strand is Professor of Education at the Oxford University Department of Education. Steve Strand has been Professor of Education at the University of Oxford since January 2013. Previously he was Professor of Education at the University of Warwick (2005-2012). Prior to that, Steve was Senior Assessment Consultant at GL Assessments, the UK’s leading educational test and assessment publisher (1998-2005) and Head of Research and Evaluation at both Wandsworth and Croydon Local Education Authorities (1988-1998). -

REGISTER of SPONSORS (Tier 4) Date: 30-June-2015

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tier 4) Date: 30-June-2015 Register of Licensed Sponsors This is a list of institutions licensed to sponsor migrants under Tier 4 of the points-based system. It shows the organisation's name (in alphabetical order), the sub tier(s) they are licensed for, and their rating against each sub tier. Legacy sponsors cannot sponsor any new students. For further information about the content of this register, please refer to the Tier 4 guidance for sponsors on the GOV.UK website. No. of Sponsors Licensed under Tier 4: 1,516 Sponsor Name Town/City Status Sub Tier Immigration Compliance 5 E Ltd London Probationary Sponsor Tier 4 General Abacus College Oxford Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abberley Hall Worcester Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbey College in London London Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Abbey College Manchester Manchester Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) ABBEY COLLEGE BIRMINGHAM Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbots Bromley School Nr. Rugeley Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbot's Hill School Hemel Hempstead Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Page 1 of 106 Sponsor Name Town/City Status Sub Tier Immigration Compliance Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) ABC School of English Ltd London Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Abercorn School