Graffiti Artists “Get Up” in Intellectual Property’S Negative Space 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Kit Years 7-12 the Writing’S on the Wall - a Short History of Street Art

Education Kit Years 7-12 The Writing’s on the Wall - A Short History of Street Art The word graffiti comes from the Italian language and means to inscribe. In European art graffiti dates back at least 17,000 years to wall paintings such as are found in the caves of Lascaux in Southern France. The paintings at Lascaux depict animals from the Paleolithic period that were of cultural importance to the people of that region. They are also believed to be spiritual in nature relating to visions experienced during ritualistic trance-dancing. Australian indigenous rock art dates back even further to about 65,000 years and like the paintings at Lascaux, Australian indigenous rock art is spiritual in nature and relates to ceremonies and the Dreaming. The history of contemporary graffiti/street art dates back about 40 years to the 1960s but it also depicts images of cultural importance to people of a particular region, the inner city, and their rituals and lifestyles. The 1960s were a time of enormous social unrest with authority challenged at every opportunity. It is no wonder graffiti, with its strong social and political agendas, hit the streets, walls, pavements, overpasses and subways of the world with such passion. The city of New York in the 1970s was awash with graffiti. It seemed to cover every surface. When travelling the subway it was often impossible to see out of the carriage for the graffiti. Lascaux, Southern France wall painting Ancient Kimberley rock art Graffiti on New York City train 1 The Writing’s on the Wall - A Short History of Street Art In 1980 an important event happened. -

The Role of Art in Enterprise

Report from the EU H2020 Research and Innovation Project Artsformation: Mobilising the Arts for an Inclusive Digital Transformation The Role of Art in Enterprise Tom O’Dea, Ana Alacovska, and Christian Fieseler This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870726. Report of the EU H2020 Research Project Artsformation: Mobilising the Arts for an Inclusive Digital Transformation State-of-the-art literature review on the role of Art in enterprise Tom O’Dea1, Ana Alacovska2, and Christian Fieseler3 1 Trinity College, Dublin 2 Copenhagen Business School 3 BI Norwegian Business School This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 870726 Suggested citation: O’Dea, T., Alacovska, A., and Fieseler, C. (2020). The Role of Art in Enterprise. Artsformation Report Series, available at: (SSRN) https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3716274 About Artsformation: Artsformation is a Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation project that explores the intersection between arts, society and technology Arts- formation aims to understand, analyse, and promote the ways in which the arts can reinforce the social, cultural, economic, and political benefits of the digital transformation. Artsformation strives to support and be part of the process of making our communities resilient and adaptive in the 4th Industrial Revolution through research, innovation and applied artistic practice. To this end, the project organizes arts exhibitions, host artist assemblies, creates new artistic methods to impact the digital transformation positively and reviews the scholarly and practi- cal state of the arts. -

Moral Rights: the Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard H

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2018 Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard H. Chused New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Land Use Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Chused, Richard H., "Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz" (2018). Articles & Chapters. 1172. https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters/1172 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard Chused* INTRODUCTION Graffiti has blossomed into far more than spray-painted tags and quickly vanishing pieces on abandoned buildings, trains, subway cars, and remote underpasses painted by rebellious urbanites. In some quarters, it has become high art. Works by acclaimed street artists Shepard Fairey, Jean-Michel Basquiat,2 and Banksy,3 among many others, are now highly prized. Though Banksy has consistently refused to sell his work and objected to others doing so, works of other * Professor of Law, New York Law School. I must give a heartfelt, special thank you to my artist wife and muse, Elizabeth Langer, for her careful reading and constructive critiques of various drafts of this essay. Her insights about art are deeply embedded in both this paper and my psyche. Familial thanks are also due to our son, Benjamin Chused, whose knowledge of the graffiti world was especially helpful in composing this paper. -

APA 6Th Edition Template

Graffiti: History, Definition and Entrepreneurship in Urban Art. Graffiti: History, Definition And Entrepreneurship In Urban Art A Master’s Thesis Presented to Dr. Loren Schmidt Heritage University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts William D. Green Heritage University 1 | P a g e Graffiti: History, Definition and Entrepreneurship in Urban Art. FACULTY APPROVAL Graffiti: The History, Definition and Entrepreneurship in Urban Art Approved for the Faculty , Faculty Advisor, Dr. Loren Schmidt , Associate Professor, English & Humanities Ann Olson 2 | P a g e Graffiti: History, Definition and Entrepreneurship in Urban Art. Abstract This thesis’ main objective is to give the general audience a better insight of what exactly graffiti art is and to show that there is a demand in the market for the art form. How this thesis portrays this is by giving a brief history of the art form; providing examples of the customs that are affiliated with graffiti art, by defining the different styles that are commonly used by graffiti artists and to provide examples of companies and urban artists either using this art on their product or urban artists finding ways to assimilate their hobby into a profession. 3 | P a g e Graffiti: History, Definition and Entrepreneurship in Urban Art. PERMISSION TO STORE I, William D. Green, do hereby irrevocably consent and authorize Heritage University Library to file the attached Thesis entitled, Graffiti: The History, Definition and Entrepreneurship in Urban Art, and make such paper available for the use, circulation, and/or reproduction by the Library. The paper may be used at Heritage University and all site locations. -

Download The

S PRING 2 013 BEAUTY OR BLIGHT? Concordia experts analyze graffiti and street art UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE CELTIC CANADIANS > EDUCATING EDUCATORS > CONSIDERING QUEER FILM Discover why over 375,000 graduates enjoy greater savings Join the growing number of graduates who enjoy greater savings from TD Insurance on home and auto coverage. Most insurance companies offer discounts for combining home and auto policies, or your good driving record. What you may not know is that we offer these savings too, plus we offer preferred rates to graduates and students of Concordia University. You’ll also receive our highly personalized service and great protection that suits your needs. Find out how much you could save. Request a quote today 1-888-589-5656 Monday to Friday: 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Saturday: 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. melochemonnex.com/concordia Insurance program sponsored by the The TD Insurance Meloche Monnex home and auto insurance program is underwritten by SECURITY NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY. The program is distributed by Meloche Monnex Insurance and Financial Services Inc. in Quebec and by Meloche Monnex Financial Services Inc. in the rest of Canada. Due to provincial legislation, our auto insurance program is not offered in British Columbia, Manitoba or Saskatchewan. *No purchase required. Contest organized jointly with Primmum Insurance Company and open to members, employees and other eligible persons belonging to employer, professional and alumni groups which have an agreement with and are entitled to group rates from the organizers. Contest ends on October 31, 2013. Draw on November 22, 2013. One (1) prize to be won. -

Juliana Abramides Dos Santos.Pdf

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO PUC-SP Juliana Abramides dos Santos Arte urbana no capitalismo em chamas: pixo e graffiti em explosão DOUTORADO EM SERVIÇO SOCIAL SÃO PAULO 2019 Juliana Abramides dos Santos DOUTORADO EM SERVIÇO SOCIAL Tese apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de Doutora em Serviço Social sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. Antônio Carlos Mazzeo. 2019 Autorizo exclusivamente para fins acadêmicos e científicos, a reprodução total ou parcial desta tese de doutorado por processos de fotocopiadoras ou eletrônicos. Assinatura: Data: E-mail: Ficha Catalográfica dos SANTOS, JULIANA Abramides Arte urbana no capitalismo em chamas: pixo e graffiti em explosão / JULIANA Abramides dos SANTOS. -- São Paulo: [s.n.], 2019. 283p. il. ; cm. Orientador: Antônio Carlos Mazzeo. Co-Orientador: Kevin B. Anderson. Tese (Doutorado em Serviço Social)-- Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Serviço Social, 2019. 1. Arte Urbana. 2. Capitalismo Contemporâneo. 3. Pixo. 4. Graffiti. I. Mazzeo, Antônio Carlos. II. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Serviço Social. III. Título.I. Mazzeo, Antônio Carlos. II. Anderson, Kevin B., co-orient. IV. Título. Banca Examinadora ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- ------------------------------------- Aos escritores/as e desenhistas do fluxo de imagens urbanas. O presente trabalho foi realizado com apoio do Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) - Número do Processo- 145851/2015-0. This study was financed in part by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) - Finance Code 001-145851/2015-0. Esta tese de doutorado jamais poderia ser escrita sem o contato e apoio de inúmeras parcerias. -

Context and Visual Culture in Recent Works of Allen Fisher and Ulli Freer

Article How to Cite: Virtanen, J 2016 Writing on: Context and Visual Culture in Recent Works of Allen Fisher and Ulli Freer. Journal of British and Irish Inno- vative Poetry, 8(1): e3, pp. 1–34, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16995/biip.20 Published: 27 May 2016 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry, which is a journal published by the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2016 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and repro- duction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. The Open Library of Humanities is an open access non-profit publisher of scholarly articles and monographs. Juha Virtanen, ‘Writing on: Context and Visual Culture in Recent Works of Allen Fisher and Ulli Freer’ (2016) 8(1): e3 Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry, DOI: http:// dx.doi.org/10.16995/biip.20 ARTICLE Writing on: Context and Visual Culture in Recent Works of Allen Fisher and Ulli Freer Juha Virtanen University of Kent, GB [email protected] This article is a study of Allen Fisher’s Proposals and SPUTTOR, and Ulli Freer’s Burner on the Buff. -

How the Commercialization of American Street Art Marks the End of a Subcultural Movement

SAMO© IS REALLY DEAD1: How the Commercialization of American Street Art Marks the End of a Subcultural Movement Sharing a canvas with an entire city of vandals, a young man dressed in a knit cap and windbreaker balances atop a subway handrail, claiming the small blank space on the ceiling for himself. Arms outstretched, he scrawls his name in loops of black spray paint, leaving behind his distinct tag that reads, “FlipOne.”2 Taking hold in the mid ‘70s, graffiti in New York City ran rampant; young artists like FlipOne tagged every inch of the city’s subway system, turning the cars into scratchpads and the platforms into galleries.3 In broad daylight, aerosolcanyeilding graffiti artists thoroughly painted the Lower East Side, igniting what would become a massive American subculture movement known as street art. Led by the nation’s most economically depressed communities, the movement flourished in the early ‘80s, becoming an outlet of expression for the underprivileged youth of America. Under state law, uncommissioned street art in the United States is an act of vandalism and thereby, a criminal offense.4 As a result of the form’s illegal status, it became an artistic manifestation of rebellion, granting street art an even greater power on account of its uncensored, defiant nature. Demonized for its association with gang violence, poverty, and crime, local governments began cracking down on inner city street art, ultimately waging war upon the movement itself. As American cities worked to reclaim their streets and rid them of graffiti, the movement eventually came to a standstill, giving way to cleaner, more prosperous inner city communities. -

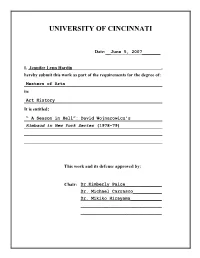

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:__June 5, 2007_______ I, Jennifer Lynn Hardin_______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Masters of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: “ A Season in Hell”: David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud in New York Series (1978-79) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr.Kimberly Paice______________ Dr. Michael Carrasco___________ Dr. Mikiko Hirayama____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ “A Season in Hell”: David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud In New York Series (1978-79) A thesis submitted to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati In candidacy for the degree of Masters of Arts in Art History Jennifer Hardin June 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) was an interdisciplinary artist who rejected traditional scholarship and was suspicious of institutions. Wojnarowicz’s Arthur Rimbaud in New York series (1978-79) is his earliest complete body of work. In the series a friend wears the visage of the French symbolist poet. My discussion of the photographs involves how they convey Wojnarowicz’s notion of the city. In chapter one I discuss Rimbaud’s conception of the modern city and how Wojnarowicz evokes the figure of the flâneur in establishing a link with nineteenth century Paris. In the final chapters I address the issue of the control of the city and an individual’s right to the city. In chapter two I draw a connection between the renovations of Paris by Baron George Eugène Haussman and the gentrification Wojnarowicz witnessed of the Lower East side. -

5Pointz Decision

Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 1 of 100 PageID #: 4939 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK --------------------------------------------------x JONATHAN COHEN, SANDRA Case No. 13-CV-05612(FB)(RLM) FABARA, STEPHEN EBERT, LUIS LAMBOY, ESTEBAN DEL VALLE, RODRIGO HENTER DE REZENDE, DANIELLE MASTRION, WILLIAM TRAMONTOZZI, JR., THOMAS LUCERO, AKIKO MIYAKAMI, CHRISTIAN CORTES, DUSTIN SPAGNOLA, ALICE MIZRACHI, CARLOS GAME, JAMES ROCCO, STEVEN LEW, FRANCISCO FERNANDEZ, and NICHOLAI KHAN, Plaintiffs, -against- G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON DECISION AVENUE OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC, and GERALD WOLKOFF, Defendants. --------------------------------------------------x MARIA CASTILLO, JAMES COCHRAN, Case No. 15-CV-3230(FB)(RLM) LUIS GOMEZ, BIENBENIDO GUERRA, RICHARD MILLER, KAI NIEDERHAUSEN, CARLO NIEVA, RODNEY RODRIGUEZ, and KENJI TAKABAYASHI, Plaintiffs, -against- Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 2 of 100 PageID #: 4940 G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON AVENUE OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC, and GERALD WOLKOFF, Defendants. -----------------------------------------------x Appearances: For the Plaintiff For the Defendant ERIC BAUM DAVID G. EBERT ANDREW MILLER MIOKO TAJIKA Eisenberg & Baum LLP Ingram Yuzek Gainen Carroll & 24 Union Square East Bertolotti, LLP New York, NY 10003 250 Park Avenue New York, NY 10177 BLOCK, Senior District Judge: TABLE OF CONTENTS I ..................................................................5 II ..................................................................6 A. The Relevant Statutory Framework . 7 B. The Advisory Jury . 11 C. The Witnesses and Evidentiary Landscape. 13 2 Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 3 of 100 PageID #: 4941 III ................................................................16 A. -

Virtual ESD Testing of Automotive LED Lighting System

2018 IEEE Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility, Signal Integrity and Power Integrity (EMC, SI & PI 2018) Long Beach, California, USA 30 July - 3 August 2018 Technical and Abstract Reviewed Papers Pages 1-692 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP18K39-POD ISBN: 978-1-5386-6622-7 1/4 Copyright © 2018 by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc. All Rights Reserved Copyright and Reprint Permissions: Abstracting is permitted with credit to the source. Libraries are permitted to photocopy beyond the limit of U.S. copyright law for private use of patrons those articles in this volume that carry a code at the bottom of the first page, provided the per-copy fee indicated in the code is paid through Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923. For other copying, reprint or republication permission, write to IEEE Copyrights Manager, IEEE Service Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854. All rights reserved. *** This is a print representation of what appears in the IEEE Digital Library. Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. IEEE Catalog Number: CFP18K39-POD ISBN (Print-On-Demand): 978-1-5386-6622-7 ISBN (Online): 978-1-5386-6621-0 Additional Copies of This Publication Are Available From: Curran Associates, Inc 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: (845) 758-0400 Fax: (845) 758-2633 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com TABLE OF CONTENTS – TECHNICAL TUESDAY TECHNICAL PAPERS Tuesday, July 31, 2018 TU-AM-2 Computational Tools and Techniques (Sponsored by TC 9) 10:30 am - 12:00 pm Chair: Scott Piper, General Motors, Milford, MI, USA Co-Chair: Yansheng Wang, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, MO, USA 10:30 am Virtual ESD Testing of Automotive LED Lighting System ........................................................ -

App. 1 950 F.3D 155 (2D Cir. 2020) United States Court of Appeals

App. 1 950 F.3d 155 (2d Cir. 2020) United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit Maria CASTILLO, James Cochran, Luis Gomez, Bien- benido Guerra, Richard Miller, Carlo Nieva, Kenji Taka- bayashi, Nicholai Khan, Plaintiffs-Appellees, Jonathan Cohen, Sandra Fabara, Luis Lamboy, Esteban Del Valle, Rodrigo Henter De Rezende, William Tramon- tozzi, Jr., Thomas Lucero, Akiko Miyakami, Christian Cortes, Carlos Game, James Rocco, Steven Lew, Francisco Fernandez, Plaintiffs-Counter- Defendants-Appellees, Kai Niederhause, Rodney Rodriguez, Plaintiffs, v. G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 Jackson Avenue Owners, L.P., 22-52 Jackson Avenue LLC, ACD Citiview Buildings, LLC, and Gerald Wolkoff, Defendants-Appellants. Nos. 18-498-cv (L), 18-538-cv (CON) August Term 2019 Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York Nos. 15-cv-3230 (FB) (RLM), 13-cv-5612 (FB) (RLM), Frederic Block, District Judge, Presiding. Argued August 30, 2020 Decided February 20, 2020 Amended February 21, 2020 Attorneys and Law Firms ERIC M. BAUM (Juyoun Han, Eisenberg & Baum, LLP, New York, NY, Christopher J. Robinson, Rottenberg Lipman Rich, P.C., New York, NY, on the brief), Eisenberg & Baum, LLP, New York, NY, for Plaintiffs-Appellees. MEIR FEDER (James M. Gross, on the brief), Jones Day, New York, NY, for Defendants-Appellants. App. 2 Before: PARKER, RAGGI, and LOHIER, Circuit Judges. BARRINGTON D. PARKER, Circuit Judge: Defendants‐Appellants G&M Realty L.P., 22‐50 Jack- son Avenue Owners, L.P., 22‐52 Jackson Avenue LLC, ACD Citiview Buildings, LLC, and Gerald Wolkoff (collec- tively “Wolkoff”) appeal from a judgment of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York (Frederic Block, J.).