Jane Goodall Bill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commitment 2014 Annual Report

THE POWER OF COMMITMENT 2014 ANNUAL REPORT 1 2014 HIGHLIGHTS BY-THE-NUMBERS Protecting Great Apes Sustainable Livelihoods Continued ongoing care for 154 chimpanzees at the Produced and distributed more than 365,000 different Tchimpounga sanctuary. kinds of trees and plants that either provide food, building materials or income for communities and reduce Released an additional seven chimpanzees on to demand for cutting down forests that would otherwise be safe, natural, expanded sanctuary sites on Tchibebe and chimpanzee habitat. Tchindzoulou islands, bringing the total to 35 now living on the islands. Provided training to 331 farmers in agroforestry and/ or animal husbandry and provided them with either tree Released seven mandrills back into Conkouati-Douli seedlings or livestock to grow and sell. In addition, JGI National Park, and started the first phase of release with distributed 100 beehives to help families produce honey five more mandrills. as a source of income. Supported 11 studies by research partners at Gombe Built nearly 700 fuel efficient stoves to help decrease Stream Research Center, which resulted in 31 scientific household costs and demand for cutting forests for papers, theses and presentations. firewood. Erected an additional ten public awareness billboards in Republic of Congo bringing the total over the halfway point to our goal of 70 total billboards in the country. Healthy Habitats Science & Technology Increased protection of 512,000 hectares (1.3 million Used crowd-sourced forest monitoring beginning in acres) of forest in the Masito-Ugalla ecosystem of Tanzania 2012 through 2014 to generate 34,347 observations through newly established reserves previously considered from Tanzania and 15,006 observations from Uganda “general land.” of chimpanzee and other wildlife presence and illegal human activities. -

Homo Habilis

COMMENT SUSTAINABILITY Citizens and POLICY End the bureaucracy THEATRE Shakespeare’s ENVIRONMENT James Lovelock businesses must track that is holding back science world was steeped in on surprisingly optimistic governments’ progress p.33 in India p.36 practical discovery p.39 form p.41 The foot of the apeman that palaeo ‘handy man’, anthropologists had been Homo habilis. recovering in southern Africa since the 1920s. This, the thinking went, was replaced by the taller, larger-brained Homo erectus from Asia, which spread to Europe and evolved into Nean derthals, which evolved into Homo sapiens. But what lay between the australopiths and H. erectus, the first known human? BETTING ON AFRICA Until the 1960s, H. erectus had been found only in Asia. But when primitive stone-chop LIBRARY PICTURE EVANS MUSEUM/MARY HISTORY NATURAL ping tools were uncovered at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, Leakey became convinced that this is where he would find the earliest stone- tool makers, who he assumed would belong to our genus. Maybe, like the australopiths, our human ancestors also originated in Africa. In 1931, Leakey began intensive prospect ing and excavation at Olduvai Gorge, 33 years before he announced the new human species. Now tourists travel to Olduvai on paved roads in air-conditioned buses; in the 1930s in the rainy season, the journey from Nairobi could take weeks. The ravines at Olduvai offered unparalleled access to ancient strata, but field work was no picnic in the park. Water was often scarce. Leakey and his team had to learn to share Olduvai with all of the wild animals that lived there, lions included. -

Jane Goodall

Jane Goodall Dame Jane Morris Goodall, DBE (born Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall on 3 April 1934) is a British primatologist, ethologist, anthropologist, and UN Messenger of Peace.Considered to be the world's foremost expert on chimpanzees, Goodall is best known for her 45-year study of social and family interactions of wild chimpanzees in Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania. She is the founder of the Jane Goodall Institute and the Roots & Shoots program, and she has worked extensively on conservation and animal welfare issues. She has served on the board of the Nonhuman Rights Project since its founding in 1996. Early years Jane Goodall was born in London, England, in 1934 to Mortimer Herbert Morris-Goodall, a businessman, and Margaret Myfanwe Joseph, a novelist who wrote under the name Vanne Morris-Goodall. As a child, she was given a lifelike chimpanzee toy named Jubilee by her father; her fondness for the toy started her early love of animals. Today, the toy still sits on her dresser in London. As she writes in her book, Reason for Hope: "My mother's friends were horrified by this toy, thinking it would frighten me and give me nightmares." Goodall has a sister, Judith, who shares the same birthday, though the two were born four years apart. Africa Goodall had always been passionate about animals and Africa, which brought her to the farm of a friend in the Kenya highlands in 1957.From there, she obtained work as a secretary, and acting on her friend's advice, she telephoned Louis Leakey, a Kenyan archaeologist and palaeontologist, with no other thought than to make an appointment to discuss animals. -

Hands-On Human Evolution: a Laboratory Based Approach

Hands-on Human Evolution: A Laboratory Based Approach Developed by Margarita Hernandez Center for Precollegiate Education and Training Author: Margarita Hernandez Curriculum Team: Julie Bokor, Sven Engling A huge thank you to….. Contents: 4. Author’s note 5. Introduction 6. Tips about the curriculum 8. Lesson Summaries 9. Lesson Sequencing Guide 10. Vocabulary 11. Next Generation Sunshine State Standards- Science 12. Background information 13. Lessons 122. Resources 123. Content Assessment 129. Content Area Expert Evaluation 131. Teacher Feedback Form 134. Student Feedback Form Lesson 1: Hominid Evolution Lab 19. Lesson 1 . Student Lab Pages . Student Lab Key . Human Evolution Phylogeny . Lab Station Numbers . Skeletal Pictures Lesson 2: Chromosomal Comparison Lab 48. Lesson 2 . Student Activity Pages . Student Lab Key Lesson 3: Naledi Jigsaw 77. Lesson 3 Author’s note Introduction Page The validity and importance of the theory of biological evolution runs strong throughout the topic of biology. Evolution serves as a foundation to many biological concepts by tying together the different tenants of biology, like ecology, anatomy, genetics, zoology, and taxonomy. It is for this reason that evolution plays a prominent role in the state and national standards and deserves thorough coverage in a classroom. A prime example of evolution can be seen in our own ancestral history, and this unit provides students with an excellent opportunity to consider the multiple lines of evidence that support hominid evolution. By allowing students the chance to uncover the supporting evidence for evolution themselves, they discover the ways the theory of evolution is supported by multiple sources. It is our hope that the opportunity to handle our ancestors’ bone casts and examine real molecular data, in an inquiry based environment, will pique the interest of students, ultimately leading them to conclude that the evidence they have gathered thoroughly supports the theory of evolution. -

ASEBL Journal

January 2019 Volume 14, Issue 1 ASEBL Journal Association for the Study of EDITOR (Ethical Behavior)•(Evolutionary Biology) in Literature St. Francis College, Brooklyn Heights, N.Y. Gregory F. Tague, Ph.D. ▬ ~ GUEST CO-EDITOR ISSUE ON GREAT APE PERSONHOOD Christine Webb, Ph.D. ~ (To Navigate to Articles, Click on Author’s Last Name) EDITORIAL BOARD — Divya Bhatnagar, Ph.D. FROM THE EDITORS, pg. 2 Kristy Biolsi, Ph.D. ACADEMIC ESSAY Alison Dell, Ph.D. † Shawn Thompson, “Supporting Ape Rights: Tom Dolack, Ph.D Finding the Right Fit Between Science and the Law.” pg. 3 Wendy Galgan, Ph.D. COMMENTS Joe Keener, Ph.D. † Gary L. Shapiro, pg. 25 † Nicolas Delon, pg. 26 Eric Luttrell, Ph.D. † Elise Huchard, pg. 30 † Zipporah Weisberg, pg. 33 Riza Öztürk, Ph.D. † Carlo Alvaro, pg. 36 Eric Platt, Ph.D. † Peter Woodford, pg. 38 † Dustin Hellberg, pg. 41 Anja Müller-Wood, Ph.D. † Jennifer Vonk, pg. 43 † Edwin J.C. van Leeuwen and Lysanne Snijders, pg. 46 SCIENCE CONSULTANT † Leif Cocks, pg. 48 Kathleen A. Nolan, Ph.D. † RESPONSE to Comments by Shawn Thompson, pg. 48 EDITORIAL INTERN Angelica Schell † Contributor Biographies, pg. 54 Although this is an open-access journal where papers and articles are freely disseminated across the internet for personal or academic use, the rights of individual authors as well as those of the journal and its editors are none- theless asserted: no part of the journal can be used for commercial purposes whatsoever without the express written consent of the editor. Cite as: ASEBL Journal ASEBL Journal Copyright©2019 E-ISSN: 1944-401X [email protected] www.asebl.blogspot.com Member, Council of Editors of Learned Journals ASEBL Journal – Volume 14 Issue 1, January 2019 From the Editors Shawn Thompson is the first to admit that he is not a scientist, and his essay does not pretend to be a scientific paper. -

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List – Updated July 1, 2021 The following AZA-accredited institutions have agreed to offer a 50% discount on admission to visiting Santa Barbara Zoo Members who present a current membership card and valid picture ID at the entrance. Please note: Each participating zoo or aquarium may treat membership categories, parking fees, guest privileges, and additional benefits differently. Reciprocation policies subject to change without notice. Please call to confirm before you visit. Iowa Rosamond Gifford Zoo at Burnet Park - Syracuse Alabama Blank Park Zoo - Des Moines Seneca Park Zoo – Rochester Birmingham Zoo - Birmingham National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium - Staten Island Zoo - Staten Island Alaska Dubuque Trevor Zoo - Millbrook Alaska SeaLife Center - Seaward Kansas Utica Zoo - Utica Arizona The David Traylor Zoo of Emporia - Emporia North Carolina Phoenix Zoo - Phoenix Hutchinson Zoo - Hutchinson Greensboro Science Center - Greensboro Reid Park Zoo - Tucson Lee Richardson Zoo - Garden Museum of Life and Science - Durham Sea Life Arizona Aquarium - Tempe City N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher - Kure Beach Arkansas Rolling Hills Zoo - Salina N.C. Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores - Atlantic Beach Little Rock Zoo - Little Rock Sedgwick County Zoo - Wichita N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island - Manteo California Sunset Zoo - Manhattan Topeka North Carolina Zoological Park - Asheboro Aquarium of the Bay - San Francisco Zoological Park - Topeka Western N.C. (WNC) Nature Center – Asheville Cabrillo Marine Aquarium -

2006 Reciprocal List

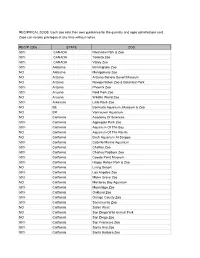

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

ALL APES GREAT and SMALL VOLUME 1: AFRICAN APES Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects Series Editor: Russell H

ALL APES GREAT AND SMALL VOLUME 1: AFRICAN APES Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects Series Editor: Russell H. Tuttle, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois This peer-reviewed book series will meld the facts of organic diversity with the continuity of the evolutionary process. The volumes in this series will exemplify the diversity of theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches currently employed by primatolo- gists and physical anthropologists. Specific coverage includes: primate behavior in natural habitats and captive settings; primate ecology and conservation; functional morphology and developmental biology of primates; primate systematics; genetic and phenotypic differ- ences among living primates; and paleoprimatology. All Apes Great and Small Volume 1: African Apes Co-edited by Biruté M. F. Galdikas, Nancy Erickson Briggs, Lori K. Sheeran, Gary L. Shapiro, and Jane Goodall ALL APES GREAT AND SMALL VOLUME 1: AFRICAN APES Co-Edited by Biruté M. F. Galdikas President Orangutan Foundation International Los Angeles, California Nancy Erickson Briggs California State University at Long Beach Long Beach, California Lori K. Sheeran California State University at Fullerton Fullerton, California Gary L. Shapiro Vice-President Orangutan Foundation International Los Angeles, California and Jane Goodall President The Jane Goodall Institute KLUWER ACADEMIC PUBLISHERS NEW YORK, BOSTON, DORDRECHT, LONDON, MOSCOW eBook ISBN: 0-306-4761-1 Print ISBN: 0-306-46757-7 ©2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers New York, Boston, Dordrecht, -

Introduction

Volume 1.qxd 9/13/2005 3:29 PM Page xlvii GGGGG INTRODUCTION The Anthropological Quest hominid ancestors, as well as ideas about the emer- gence of social organizations and cultural adaptations. Anthropology is the study of humankind in terms of As a result of both research over scores of decades and scientific inquiry and logical presentation. It strives for the convergence of facts and concepts, anthropologists a comprehensive and coherent view of our own species now offer a clearer picture of humankind’s natural within dynamic nature, organic evolution, and socio- history and global dominance. cultural development. The discipline consists of five With the human being as its focus, the discipline major, interrelated areas: physical/biological anthro- of anthropology mediates between the natural and pology, archaeology, cultural/social anthropology, social sciences while incorporating the humanities. Its linguistics, and applied anthropology. The anthropo- acceptance and use of discoveries in biology, for logical quest aims for a better understanding of and example, the DNA molecule, and its attention to rele- proper appreciation for the evolutionary history, vant ideas in the history of philosophy, such as the sociocultural diversity, and biological unity of concepts presented in the writings of Marx and humankind. Anthropologists see the human being as Nietzsche, make anthropology a unique field of study a dynamic and complex product of both inherited and a rich source for the relevant application of facts, genetic information and learned social behavior within a cultural milieu; symbolic language as articu- late speech distinguishes our species from the great apes. Genes, fossils, artifacts, monuments, languages, and societies and their cultures are the subject matter of anthropology. -

Jane Goodall: a Timeline 3

Discussion Guide Table of Contents The Life of Jane Goodall: A Timeline 3 Growing Up: Jane Goodall’s Mission Starts Early 5 Louis Leakey and the ‘Trimates’ 7 Getting Started at Gombe 9 The Gombe Community 10 A Family of Her Own 12 A Lifelong Mission 14 Women in the Biological Sciences Today 17 Jane Goodall, in Her Own Words 18 Additional Resources for Further Study 19 © 2017 NGC Network US, LLC and NGC Network International, LLC. All rights reserved. 2 Journeys in Film : JANE The Life of Jane Goodall: A Timeline April 3, 1934 Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall is born in London, England. 1952 Jane graduates from secondary school, attends secretarial school, and gets a job at Oxford University. 1957 At the invitation of a school friend, Jane sails to Kenya, meets Dr. Louis Leakey, and takes a job as his secretary. 1960 Jane begins her observations of the chimpanzees at what was then Gombe Stream Game Reserve, taking careful notes. Her mother is her companion from July to November. 1961 The chimpanzee Jane has named David Greybeard accepts her, leading to her acceptance by the other chimpanzees. 1962 Jane goes to Cambridge University to pursue a doctorate, despite not having any undergraduate college degree. After the first term, she returns to Africa to continue her study of the chimpanzees. She continues to travel back and forth between Cambridge and Gombe for several years. Baron Hugo van Lawick, a photographer for National Geographic, begins taking photos and films at Gombe. 1964 Jane and Hugo marry in England and return to Gombe. -

Black-Footed Ferret Media

coming soon to Canada The black-footed ferret returns to the Canadian prairies The black-footed ferret is one of North America’s most endangered animals and just a few decades ago, was thought to be extinct. Now after several years of international effort, the black-footed ferret will be reintroduced into the wild in Canada in Fall 2009. In 2004, the Toronto Zoo, in partnership with Parks Canada, US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), Calgary Zoo, private stakeholders and other organizations established a joint Black-footed Ferret/Black-tailed Prairie Dog Canadian Recovery Team to look at the potential for reintroducing black-footed ferrets into Grasslands National Park (GNP) in Saskatchewan. After a lot of hard work on many levels, reintroduction of black-footed ferrets into black-footed ferret kits GNP is now planned for the fall of 2009. 4 spring 2009 collections back from near-extinction The black-footed ferret is the only native ferret known to North America and is listed as one of North America’s most endangered species. Ferrets prey almost exclusively on prairie dogs and inhabit prairie dog burrows. Loss of prairie dogs due to wide-scale extermination, agricultural conversion of their habitat, and epidemics of sylvatic plague (black plague) have resulted in the loss of about 95% of the ferret range since the 1800s. The black-footed ferret was thought to be extinct in the mid 1970s but in 1981 there was a dramatic discovery of a small population in Meetetse, Wyoming. Between 1985 and 1987, 18 ferrets were brought into captivity for the purpose of setting up a captive breeding and reintroduction program to save the species. -

Annu Al R Ep Or T 2016–2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2016–2017 ANNUAL Goddard Earth Sciences Technology and Research Studies and Investigations GESTAR Staff Hanson, Heather Miller, Kevin Wen, Guoyong Achuthavarier, Deepthi Holdaway, Dan Mohammed, Priscilla Wiessinger, Scott Ahamed, Aakash Humberson, Winnie Monroe, Brian Wright, Ernie Amatya, Pukar Hurwitz, Margaret Moran, Amy Yang, Weidong Andrew, Andrea Ibrahim, Amir Ng, Joy Yang, Yuekui Anyamba, Assaf Jackson, Katrina Norris, Peter Yao, Tian Aquila, Valentina Jentoft-Nilsen, Marit Nowottnick, Ed Zhang, Cheng Armstrong, Amanda Jepsen, Rikke Oda, Tom Zhang, Qingyuan Arnold, Nathan Jethva, Hiren Olsen, Mark Zhou, Yaping Barker, Ryan Jin, Daeho Orbe, Clara Ziemke, Jerald Beck, Jefferson Jin, Jianjun Patadia, Falguni Bell, Benita Ju, Junchang Patel, Kiran GESTAR Integrated Belvedere, Debbie Keating, Shane Paynter, Ian Project Team (IPT) Bensusen, Sally Kekesi, Alex Pelc, Joanna Ball, Carol Bollian, Tobias Keller, Christoph Peng, Jinzheng Corso, Bill Bridgman, Tom Khan, Maudood Poje, Lisa Espiritu, Angie Brucker, Ludovic Kim, Dongchul Potter, Gerald Gardner, Jeanette Buchard, Virginie Kim, Dongjae Prescott, Ishon Houghton, Amy Carvalho, David Kim, Hyokyung Prive, Nikki Morgan, Dagmar Radcliff, Matthew Samuel, Elamae ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Castellanos, Patricia Kim, Min-Jeong Cede, Alexander Knowland, Emma Reale, Oreste Celarier, Ed Kolassa, Jana Rousseaux, Cecile Technical Editor Cetinic, Ivona Korkin, Sergey Sayer, Andy Amy Houghton Chang, Yehui Kostis, Helen-Nicole Schiffer, Robert Chatterjee, Abhishek Kowalewski, Matthew Schindler,