Joshua, Judges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Book of Judges – “Downward Spiral”

The pattern devolves until there is absolute darkness and despair THE BOOK OF JUDGES – “DOWNWARD SPIRAL” Judges 8 What is the basic message of Judges? 24 And Gideon said to them, “Let me make a request of you: every one of 27 • the repeated failures of Israel to love God you give me the earrings from his spoil.” … And Gideon made an and the inadequacy of all the judges to truly rescue Israel ephod of it and put it in his city, in Ophrah. And all Israel whored after it there, and it became a snare to Gideon and to his family. The Book of Judges is a series of redemption cycles: 30 Now Gideon had seventy sons, his own offspring, for he had many (1) the people rebel against God wives. 31 And his concubine who was in Shechem also bore him a son, (2) God allows the people to suffer from their sins and he called his name Abimelech. 32 And Gideon the son of Joash died in (3) the people cry out to God for deliverance a good old age and was buried in the tomb of Joash his father, at Ophrah (4) God sends a judge – a deliverer of the Abiezrites. (5) there is a period of rest and peace Judges 13:1-2 1 And the people of Israel again did what was evil in the sight of the You see this pattern in the first judge – Othniel | Judges 3:7-12 LORD, so the LORD gave them into the hand of the Philistines for forty 2 Stage 1 – Israel rebels against God years. -

The Book of Judges Lesson One Introduction to the Book

The Book of Judges Lesson One Introduction to the Book by Dr. John L. May I. The Historical Background - Authorship Dates of the events of the book are uncertain. It is a book about and to the children of Israel (Judges 1:1). Since the book is a continuation of history following the book of Joshua, many scholars believe that it was written after the death of Joshua (after 1421 BC). However, others think that it was written even later than this, for Judges 18:1 and 19:1 imply that there was a king in Israel at the time of writing. That would necessitate a date of 1095 BC or later. If you base your belief upon Judges 1:21, 29, a date of approximately 1000 BC would be a date that would place its writing during the time of Samuel and the reign of the kings. This would tie in nicely with the Jewish tradition that the author was Samuel. There is neither an inspired statement nor an implication as to the place of composition To determine the time span involved in this book, it is unlikely that the years each judge is said to have ruled could be added together, for the total would exceed 490 years. However, Wesley states in his notes on the Book of Judges that the total is only 299 years. The reason for this is that their years of service may coincide or overlap with the years of some or other of the judges and this allows Wesley to arrive at his figure. -

The Role of the Quote from Psalm 82 in John 10:34-36 Colin Liske Concordia Seminary, St

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Master of Divinity Thesis Concordia Seminary Scholarship 2-1-1968 The Role of the Quote from Psalm 82 in John 10:34-36 Colin Liske Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.csl.edu/mdiv Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Liske, Colin, "The Role of the Quote from Psalm 82 in John 10:34-36" (1968). Master of Divinity Thesis. 85. http://scholar.csl.edu/mdiv/85 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Divinity Thesis by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 8S 5036 4%45•w. 45-5 CONCORDIA SEMINARY LIBRARX ST. LOWS, MISSOURI TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS . * . ***** It . Chapter I. THE NEED FOR AN EXAMINATION . o . The Diversity in Interpretations . 1 The Controversy in the Missouri--Synod . 3 Methodology Employed 5 Preliminary Summary . 0' C9 0- • 0 0 0 . 5 II. PRESENT POSITION OF RESEARCH . Or 0 8 III. THE INTERPRETATION OF PSALM 82 . 26 Modern Exegesis of Psalm 82 *** . 26 Other Interpretations of Psalm 82 . 31 Summary and Conclusions . 34 IV. THE CONCEPT OF BLASPHEMY IN RABBINIC EXEGESIS OF THE OLD TESTAMENT . 35 Rabbinic Exegesis of Exodus 22:28 . it 35 Rabbinic Exegesis of Numbers 15:30f. Or • 38 Rabbinic Exegesis of Leviticus 24:11ff. 42 Slimmary and Conclusions . -

Judges-Study-Guide.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Tips for Reading Judges Overview and Outline Map of Israel’s Tribes and Judges Study Guide: Week One Day 1: Monday, September 21 ( Judges 1) Day 2: Tuesday, September 22 ( Judges 2) Day 3: Wednesday, September 23 ( Judges 3) Day 4: Tursday, September 24 ( Judges 4-5) Day 5: Friday, September 25 ( Judges 6) Study Guide: Week Two Day 6: Monday, September 28 ( Judges 7) Day 7: Tuesday, September 29 ( Judges 8) Day 8: Wednesday, September 30 ( Judges 9) Day 9: Tursday, October 1 (Judges 10) Day 10: Friday, October 2 (Judges 11) Study Guide: Week Tree Day 11: Monday, October 5 (Judges 12) Day 12: Tuesday, October 6 (Judges 13) Day 13: Wednesday, October 7 (Judges 14) Day 14: Tursday, October 8 (Judges 15) Day 15: Friday, October 9 (Judges 16) Study Guide: Week Four Day 16: Monday, October 12 (Judges 17) Day 17: Tuesday, October 13 (Judges 18) Day 18: Wednesday, October 14 (Judges 19) Day 19: Tursday, October 15 (Judges 20) Day 20: Friday, October 16 (Judges 21) TIPS FOR READING THROUGH JUDGES For every passage you read, here's a process we suggest for your reading: • Take a moment to pray and ask God to help you understand and apply what you read. • Read the passage. • Ask, "Say What?" -- Go back through your reading and ask questions like: What did it say? • What did I learn about God? About myself? About life? What insights do I gain? • Ten ask, "So What?" -- Imagine someone read that same passage and asked you, "So what? What does this have to do with life today?" What's the answer? What universal lesson or life teaching does God communicate through this passage? • Finally, ask "Now What?" -- Ask God what He wants you to do with what you read. -

Judges 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Judges 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The English title, "Judges," comes to us from the Latin translation (Vulgate), which the Greek translation (Septuagint) influenced. In all three languages, the title means "judges." This title is somewhat misleading, however, because most English-speaking people associate the modern concept of a "judge" with Israel's "judges." As we shall see, judges then were very different from judges now. The Hebrew title is also "Judges" (Shophetim). The book received its name from its principal characters, as the Book of Joshua did. The "judge" in Israel was not a new office during the period of history that this book records. Moses had ordered the people to appoint judges in every Israelite town to settle civil disputes (Deut. 16:18). In addition, there was to be a "chief justice" at the tabernacle who would, with the high priest, help settle cases too difficult for the local judges (Deut. 17:9). Evidently there were several judges at the tabernacle who served jointly as Israel's "Supreme Court" (Deut. 19:17). When Joshua died, God did not appoint a man to succeed him as the military and political leader of the entire nation of Israel. Instead, each tribe was to proceed to conquer and occupy its allotted territory. As the need arose, God raised up several different individuals who were "judges," in various parts of Israel at various times, to lead segments of the Israelites against local enemies. In the broadest sense, the Hebrew word shophet, translated "judge," means "bringer of justice." The word was used in ancient Carthage and Ugarit to describe civil magistrates.1 1Charles F. -

The Meaning of the Minor Judges: Understanding the Bible’S Shortest Stories

JETS 61/2 (2018): 275–85 THE MEANING OF THE MINOR JUDGES: UNDERSTANDING THE BIBLE’S SHORTEST STORIES KENNETH C. WAY* Abstract: The notices about the so-called “minor judges” (Judg 3:31; 10:1–5; 12:8–15) are strategically arranged in the literary structure of the book of Judges. They are “minor” only in the sense that they are shorter than the other stories, but their selective thematic emphases (espe- cially on foreign deliverers, royal aspirations, outside marriages, “canaanization,” the number twelve, etc.) indicate that they are included with editorial purpose. The minor judges therefore have major importance for understanding the theological message of the book. Key words: book of Judges, canaanization, donkeys, foreigners, marriage with outsiders, minor judges, royal aspirations, seventy, twelve The book of Judges is a somewhat neglected book in Christian pulpits and Bible curricula today. If the stories of Judges are known or taught, usually only the so-called “major” judges attract interest while the remaining narratives (especially from chapters 1–2, 17–21) suffer from neglect. But the so-called “minor” judges are perhaps the most neglected parts of the book, no doubT because of their posi- tioning (beTween the major cycles), brevity, and Their presumed unimporTance which may derive from the unfortunate label “minor.” But iT is my contention that the three passages (3:31; 10:1–5; 12:8–15)1 de- scribing the minor judges conTribute a great deal to the theological meaning of the book of Judges because they reinforce the progressive patterns and themes of the whole book, provide thematic transitions beTween cycles, and bring The ToTal num- ber of leaders to twelve in order to indict all Israel. -

The Book of Judges

Judges 1:1 1 Judges 1:10 The Book of Judges 1 Now after the death of Joshua it came to pass, that the children of Israel asked the LORD, saying, Who shall go up for us against the Canaanites first, to fight against them? 2 And the LORD said, Judah shall go up: behold, I have delivered the land into his hand. 3 And Judah said unto Simeon his brother, Come up with me into my lot, that we may fight against the Canaanites; and I likewise will go with thee into thy lot. So Simeon went with him. 4 And Judah went up; and the LORD delivered the Canaanites and the Perizzites into their hand: and they slew of them in Bezek ten thousand men. 5 And they found Adoni- bezek in Bezek: and they fought against him, and they slew the Canaanites and the Perizzites. 6 But Adoni-bezek fled; and they pursued after him, and caught him, and cut off his thumbs and his great toes. 7 And Adoni-bezek said, Threescore and ten kings, having their thumbs and their great toes cut off, gathered their meat under my table: as I have done, so God hath requited me. And they brought him to Jerusalem, and there he died.*† 8 Now the children of Judah had fought against Jerusalem, and had taken it, and smitten it with the edge of the sword, and set the city on fire. 9 ¶ And afterward the children of Judah went down to fight against the Canaanites, that dwelt in the mountain, and in the south, and in the valley.‡ 10 And Judah went against the Canaanites that dwelt in Hebron: (now the name of Hebron before was Kirjath-arba:) and they slew * 1.7 their thumbs…: Heb. -

The Book of Judges

1 Survey of the Old Testament – The Book of Judges INTRODUCTION: The events described in the book of Judges took place during the period between after the Joshua’s death to the period before the birth of Samuel the prophet. The time during which God gave Israel “judges” to deliver them from oppression by their enemies in Canaan. Judges has 21 chapters. AUTHOR: Likely to be Samuel or Ezra. DATE WRITTEN: 1086-1035 B.C. (?) PURPOSES: To review Israel's history following the conquest and prior to the Monarchy; and to demonstrate the consequence of sinful rebellion, in spite of God's repeated gracious provision of political and spiritual leaders. MAIN THEME: This book records for us the work of 13 of the 15 judges called by the Lord, who were actually military leaders during this period of the history of Israel. It also portrays for us the roller coaster ride of history depicting the rise and fall of Israel as God’s people where we will see a series of relapses into idolatry and then followed by oppressions by Israel's enemies because of their evil ways. It was during these different periods where we will find a number of heroic judges whom God had raised to become the deliverers of Israel, when Israel was sincerely penitent of their sins. ISRAEL’S 13 JUDGES 3:9 - Othniel 3:15 - Ehud 3:31 - Shamgar 4:4 - Deborah 6:13 - Gideon 9:1 - Abimelech 10:1 - Tola 10:3- Jair 11:1 - Jephthah 12:8 - Ibzan 12:11 - Elon 12:13 - Abdon 14:1 - Samson OUTLINE: This book consists of three major periods. -

The Biblical Canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church

Anke Wanger THE-733 1 Student Name: ANKE WANGER Student Country: ETHIOPIA Program: MTH Course Code or Name: THE-733 This paper uses [x] US or [ ] UK standards for spelling and punctuation The Biblical Canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church 1) Introduction The topic of Biblical canon formation is a wide one, and has received increased attention in the last few decades, as many ancient manuscripts have been discovered, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the question arose as to whether the composition of the current Biblical canon(s) should be re-evaluated based on these and other findings. Not that the question had actually been settled before, as can be observed from the various Church councils throughout the last two thousand years with their decisions, and the fact that different Christian denominations often have very different books included in their Biblical Canons. Even Churches who are in communion with each other disagree over the question of which books belong in the Holy Bible. One Church which occupies a unique position in this regard is the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church. Currently, it is the only Church whose Bible is comprised of Anke Wanger THE-733 2 81 Books in total, 46 in the Old Testament, and 35 in the New Testament.1 It is also the biggest Bible, according to the number of books: Protestant Bibles usually contain 66 books, Roman Catholic Bibles 73, and Eastern Orthodox Bibles have around 76 books, sometimes more, sometimes less, depending on their belonging to the Greek Orthodox, Slavonic Orthodox, or Georgian -

March 5 Small Group Curriculuum

March 5, 2017 Focal Passage: Judges 13 -16 Key Phrase: The Fall and Our Decisions Key Question: Will you make decisions by the Fall or by faith? Key Facts: • The book of Judges tells us the history of Israel between the time of Joshua’s death and the ministry of Samuel. During this time period (1375-1050 B.C.), Israel had twelve judges, including Samson who was the last judge. The book was most likely written between 1040-1020 B.C. • The events in Judges followed a pattern of the Israelites living in peace while serving and loving God. Then the Israelites would worship idols and forsake God. God would allow a neighboring nation to fight and rule over them. The Israelites would then turn to God and ask forgiveness. God would then forgive them and send a judge to conquer their enemy. • The Nazirite Vow was a vow which had a sacred purpose. The vow was to set apart the person for service to the Lord. It was usually temporary; however Samson’s was to be permanent. The vow required three commitments: abstinence from the fruit of the vine; cutting one’s hair and avoiding dead bodies. • To make a decision by faith requires the answer to three important questions: 1. Does this decision advance God’s life mission for me? 2. Is this decision about you or me? 3. Does this decision take seriously the fear of the Lord? (Dr. Avant) • The fear of the Lord is a dread of living apart from God and His plan. (Dr. -

Introduction to the Book of Judges

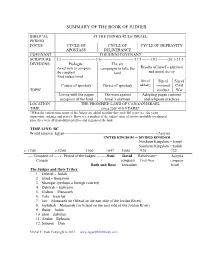

SUMMARY OF THE BOOK OF JUDGES BIBLICAL #5 THE JUDGES RULE ISRAEL PERIOD FOCUS CYCLE OF CYCLE OF CYCLE OF DEPRAVITY APOSTASY DELIVERANCE COVENANT THE SINAI COVENANT SCRIPTURE 1:1--------------------------3:6--------------------------17:1-------19:1--------20:1-21:5 DIVISIONS Prologue: The six -Israel fails to complete campaigns to take the Results of Israel’s spiritual the conquest land and moral decay -God judges Israel Sin of Sin of Sin of Causes of apostasy Curses of apostasy idolatry immoral Civil TOPIC conduct War Living with the pagan The wars against Adopting pagan customs occupiers of the land Israel’s enemies and religious practices LOCATION THE PROMISED LAND OF CANAAN/ISRAEL TIME circa 350/ 410 YEARS* *When the various time spans of the Judges are added together they total 410 years (i.e., the years oppression, judging, and peace). However, a number of the judges’ time of service probably overlapped since they were all from different tribes and regions of the land. TIME LINE: BC World Empire: Egypt------------------------------------------------------------------------Assyria UNITED KINGDOM --- DIVIDED KINGDOM Northern Kingdom = Israel Southern Kingdom = Judah c. 1300 c.1200 1100 1047 1000 930 722 ---- Conquest of ---- c. Period of the Judges --------Saul David Rehoboam= Assyria Canaan / conquers Civil War conquers Ruth and Boaz Jerusalem Israel The Judges and their Tribes: 1. Othniel – Judah 2. Ehud – Benjamin 3. Shamgar (perhaps a foreign convert) 4. Deborah – Ephraim 5. Gideon – Manasseh 6. Tola – Issachar 7. Jair – Manasseh (in Gilead on the east side of the Jordan River) 8. Jephthah – Manasseh (in Gilead on the east side of the Jordan River) 9. -

Judges Bible Studies

Judges Bible Studies Study Judges Title Main Character 1 1:1-2:5 God’s People Intro 1 2 2:6-3:6 God is our Judge Intro 2 3 3:7-31 Expect the Unexpected Othniel & Ehud 4 ch 4-5 Willing Leadership Deborah 5 ch 6-8 Strength in Weakness Gideon 6 9:1-10:5 Bad Leadership Abimelek 7 10:6-12:15 Unlikely Leadership Jephthah 8 ch 13-16 One for Many Samson 9 ch 17-21 Without a King Appendix 1 & 2 Judges was a time of heroes, of daring rescues and mighty warriors, or merciless enemies and epic battles; a time of fear, a time of revenge, a time when every man did what was right in his own eyes. Or that's how the movie trailer would go. The book of Judges is certainly a dark and gruesome part of the Bible, in which Israel lurches from sin to judgement to salvation and back again with grim regularity. Yet it contains strong warnings and encouragements for us as Christians today. Matthias Media 1 Background Genesis God made promises to Abraham in Gen 12:1-3 The LORD had said to Abram, “Go from your country, your people and your father’s household to the land I will show you. I will make you into a great nation [many descendants], and I will bless you; I will make your name great, and you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and whoever curses you I will curse; and all peoples on earth will be blessed through you.