Science Chronicles December 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chess Players

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2013 The hesC s Players Gerry A. Wolfson-Grande [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Fiction Commons, Leisure Studies Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wolfson-Grande, Gerry A., "The heC ss Players" (2013). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 38. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/38 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chess Players A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Gerry A. Wolfson-Grande May, 2013 Mentor: Dr. Philip F. Deaver Reader: Dr. Steve Phelan Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida The Chess Players By Gerry A. Wolfson-Grande May, 2013 Project Approved: ______________________________________ Mentor ______________________________________ Reader ______________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ______________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College Acknowledgments I would like to thank several of my MLS professors for providing the opportunity and encouragement—and in some cases a very long rope—to apply my chosen topic to -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Escaping the Honeytrap Representations and Ramifications of the Female Spy on Television Since 1965 Karen K. Burrows Submitted in fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media and Cultural Studies at the University of Sussex, May 2014 3 University of Sussex Karen K. Burrows Escaping the Honeytrap: Representations and Ramifications of the Female Spy on Television Since 1965 Summary My thesis interrogates the changing nature of the espionage genre on Western television since the middle of the Cold War. It uses close textual analysis to read the progressions and regressions in the portrayal of the female spy, analyzing where her representation aligns with the achievements of the feminist movement, where it aligns with popular political culture of the time, and what happens when the two factors diverge. I ask what the female spy represents across the decades and why her image is integral to understanding the portrayal of gender on television. I explore four pairs of television shows from various eras to demonstrate the importance of the female spy to the cultural landscape. -

Stuck Between a Rook and a Hard Place

KEOI3-02 Stuck Between a Rook and a Hard Place ® A One-Round D&D LIVING GREYHAWK Introductory Keoland Regional Adventure Version 1.1 by Christian J. Alipounarian When the favorite chess set of the Earl of Linth is stolen, some fledgling heroes are charged with its recovery. But what does this have to do with… flumphs? This adventure is an introductory module for 1st-level characters. Based on the original DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® rules created by E. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson and the new DUNGEONS & DRAGONS game designed by Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook, Skip Williams, Richard Baker, and Peter Adkison. This game product contains no Open Game Content. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author. To learn more about the Open Gaming License and the d20 system license, please visit www.wizards.com/d20 DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, GREYHAWK and RPGA are registered trademarks of Wizards of the Coast, Inc. LIVING GREYHAWK is a trademark of Wizards of the Coast, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. This scenario is intended for tournament use only and may not be reproduced without approval of the RPGA Network. The players are free to use the game rules to learn about Introduction equipment and weapons their characters are carrying. That said, you as the DM can bar the use of even core This is an RPGA® Network scenario for the Dungeons rulebooks during certain times of play. For example, the & Dragons® game. A four-hour time block has been players are not free to consult the Dungeon Master’s allocated for each round of this scenario, but the actual Guide when confronted with a trap or hazard, or the playing time will be closer to three and a half hours. -

Terrorism, Ethics and Creative Synthesis in the Post-Capitalist Thriller

The Post 9/11 Blues or: How the West Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Situational Morality - Terrorism, Ethics and Creative Synthesis in the Post-Capitalist Thriller Patrick John Lang BCA (Screen Production) (Honours) BA (Screen Studies) (Honours) Flinders University PhD Dissertation School of Humanities and Creative Arts (Screen and Media) Faculty of Education, Humanities & Law Date of Submission: April 2017 i Table of Contents Summary iii Declaration of Originality iv Acknowledgements v Chapter One: A Watershed Moment: Terror, subversion and Western ideologies in the first decade of the twenty-first century 1 Chapter Two: Post-9/11 entertainment culture, the spectre of terrorism and the problem of ‘tastefulness’ 18 A Return to Realism: Bourne, Bond and the reconfigured heroes of 21st century espionage cinema 18 Splinter cells, stealth action and “another one of those days”: Spies in the realm of the virtual 34 Spies, Lies and (digital) Videotape: 21st Century Espionage on the Small Screen 50 Chapter Three: Deconstructing the Grid: Bringing 24 and Spooks into focus 73 Jack at the Speed of Reality: 24, torture and the illusion of real time or: “Diplomacy: sometimes you just have to shoot someone in the kneecap” 73 MI5, not 9 to 5: Spooks, disorder, control and fighting terror on the streets of London or: “Oh, Foreign Office, get out the garlic...” 91 Chapter Four: “We can't say anymore, ‘this we do not do’”: Approaching creative synthesis through narrative and thematic considerations 108 Setting 108 Plot 110 Morality 111 Character 114 Cinematic aesthetics and the ‘culture of surveillance’ 116 The role of technology 119 Retrieving SIGINT Data - Documenting the Creative Artefact 122 ii The Section - Series Bible 125 The Section - Screenplays 175 Episode 1.1 - Pilot 175 Episode 1.2 - Blasphemous Rumours 239 Episode 1.9 - In a Silent Way 294 Bibliography 347 Filmography (including Television and Video Games) 361 iii Summary The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 have come to signify a critical turning point in the geo-political realities of the Western world. -

“For Queen. for Country. for Kicks.”: Post-Apocalyptic Patriotism, Youth and Gender in Spooks: Code 9 (BBC Three, 2008) Chri

“For Queen. For Country. For Kicks.”: Post-Apocalyptic Patriotism, Youth and Gender in Spooks: Code 9 (BBC Three, 2008) Christine Cornea Spooks: Code 9 (S:C9) was commissioned by BBC Three for broadcast in summer 2008 as a youth-oriented “spin-off” series related to BBC One’s long-running, adult spy series, Spooks (2002-11). The narrative setting for this new series was, however, markedly different from the original Spooks: while the seasoned London-based spies in Spooks repeatedly succeed in defending a present-day Britain from terrorist attack, S:C9’s young and inexperienced team of MI5 recruits find themselves in a near-future Britain, approximately eleven months after the terrorist detonation of a nuclear bomb at the 2012 London Olympics has fundamentally altered the country’s geopolitical landscape. S:C9 is, therefore, not only differentiated from its parent series by a temporal shift, but also by a post-apocalyptic backdrop that presents its audience with the prospect of life in a society transformed by terrorism. In this article, I will be arguing that S:C9 employs nationalistic and conservative viewpoints that counter the rise of more progressive views evident in British youth culture around the time it was first broadcast. Formal aspects of this series will therefore be analysed with reference to relevant historical events and socio-cultural context in looking at the ambivalent and, at times, crudely dismissive ways in which this series engages with the concerns of youth audiences. In religious eschatology, the apocalypse is the ultimate moment of divine retribution, bringing the end of the world to an individual, a group of people, or all people. -

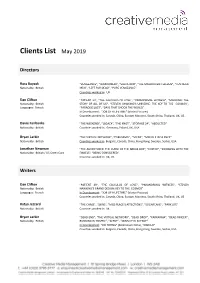

Clients List May 2019

Clients List May 2019 Directors Ross Boyask “VENGEANCE”, “WARRIORESS”, “SALVATION”, “THE MAGNIFICENT ELEVEN”, “TEN DEAD Nationality: British MEN”, “LEFT FOR DEAD”, “PURE VENGEANCE”. Countries worked in: UK Dan Clifton "PATIENT 39", "THE CALCULUS OF LOVE", "PARANORMAL WITNESS", "MANKIND: THE Nationality: British STORY OF ALL OF US", "STEVEN HAWKING'S UNIVERSE: THE KEY TO THE COSMOS", Languages: French “PARADISE LOST”, “DAYS THAT SHOOK THE WORLD”. In Development: “JOB OF A LIFETIME” (Vortex Pictures) Countries worked in: Canada, China, Europe, Morocco, South Africa, Thailand, UK, US.. Davie Fairbanks "THE WEEKEND", “LEGACY”, “THE KNOT”, “STORAGE 24”, “ABDUCTED” Nationality: British Countries worked in: Germany, Poland, UK, USA. Bryan Larkin “THE VIRTUAL NETWORK”, “PARKARMA”, “SCENE”, “MIRACLE IN SILENCE”. Nationality: British Countries worked in: Bulgaria, Canada, China, Hong Kong, Sweden, Serbia, USA Jonathan Newman "THE ADVENTURER: THE CURSE OF THE MIDAS BOX", "FOSTER", "SWINGING WITH THE Nationality: British / US Green Card FINKELS", "BEING CONSIDERED". Countries worked in: UK, US. Writers Dan Clifton "PATIENT 39", "THE CALCULUS OF LOVE", "PARANORMAL WITNESS", "STEVEN Nationality: British HAWKING'S GRAND DESIGN: KEY TO THE COSMOS". Languages: French In Development: “JOB OF A LIFETIME” (Vortex Pictures) Countries worked in: Canada, China, Europe, Morocco, South Africa, Thailand, UK, US.. Katya Jezzard "THE CHASE", "SKINS", "MISS PLACE'S AFFECTIONS", "SUGARCANE", "PARK LIFE". Nationality: British Countries worked in: UK. Bryan Larkin “DEAD -

Semantron 20 Summer 2020

Semantron 20 Summer 2020 Semantron was founded in 1992 by Dr. Jan Piggott (Head of English, and then Archivist at the College) together with one of his students, Richard Scholar (now Senior Tutor at Oriel College, Oxford and Professor of French and Comparative Literature). The photographs on the front and back covers, and those which start each section, are by Ed Brilliant. Editor’s introduction: ex umbris Neil Croally Summer 2020 Torn between the war against cliché and the rhetoric of praeteritio In late March, purely for entertainment’s sake, I had recourse to the guilty pleasure of watching some episodes of Spooks.1 Soon this turned into an obsessive need to watch the episodes of all ten series. Yes, that is nearly 100 hours of television – for someone who does not own a television. But what was the attraction? At first, I merely indulged a love for representations of the secret world, however inane or fantastic. Co-incidentally and (I suppose) remarkably, there were the Dulwich connections: not only of two of the starring actors, Rupert Penry-Jones and Raza Jaffrey, but also of the use of Sydenham Hill station and the nearby woods as the site of a secret assignation away from the febrile atmosphere of the ‘grid’, and of Crystal Palace Sports Centre as the place where a jihadi cell met under cover of a weekly five-a-side knockabout. But moving through the series, I began to marvel at two apparently incompatible features of the show. The first was the wish, unsurprising in a series about the security services, to dive boldly into ethical dilemmas, more specifically into an examination of Utilitarianism.2 One can only admire the direct, no-nonsense way in which centuries of philosophical reflection are cast aside, as the spies come down without fail in favour of the majoritarian position, whatever the cost to individuals and to themselves. -

Kathleen Singles Alternate History Narrating Futures

Kathleen Singles Alternate History Narrating Futures Edited by Christoph Bode Volume 5 Kathleen Singles Alternate History Playing with Contingency and Necessity The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) / ERC grant agreement no. 229135. Dissertation, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, 2012. ISBN 978-3-11-027217-8 e-ISBN 978-3-11-027247-5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de . © 2013 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: PTP-Berlin Protago-TEX-Production GmbH, Berlin Printing and binding: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Content 1 Introduction | 1 1.1 Contexts: Alternate Histories and Future Narratives | 1 1.2 Methodology | 4 1.3 Proceedings and Theses | 6 1.4 Selection of Primary Sources | 10 1.4.1 Medium vs. Genre | 10 1.4.2 The International Spectrum | 11 2 The Poetics of Alternate History | 14 2.1 ‘History’ in Alternate History | 26 2.1.1 The Postmodern Challenge to History | 26 2.1.2 Referentiality: Possible-worlds Theory | 33 2.1.3 ‘History’ as the Normalized Narrative of the Past | 43 -

The Rook Ep.1 23.11.16.Fdx

THE ROOK Episode 1 "Pilot" by Sam Holcroft & Al Muriel Draft – 23.11.16 THE ROOK "PILOT" TEASER EXT. HYDE PARK (LONDON) – NIGHT RAIN. Pouring, driving rain. CLOSE ON – a young woman's face, lying on muddy, torn-up grass. Eyes closed, rivulets of rain dripping from her hair, nose. She has TWO SWOLLEN BLACK EYES and bloody, red-raw lips. Unconscious? Dead? She is MYFANWY THOMAS (early 30s). As we pull back, we see she is thin, pale. Her expensive suit and overcoat are soaked through, muddy, torn. MYFANWY (V.O.) Dear You. Myfanwy jolts awake, gasps for breath. Blinks her eyes against the stinging rain. Pushes herself upright on the sodden grass. MYFANWY (V.O.) The body you are wearing used to be mine. She looks down at her muddy hands – eyes wide with panic ("Whose hands are these?"). A jolt of pain – she clutches her ribs, grimacing. MYFANWY (V.O.) I'm writing this letter for you to read in the future. She struggles to her feet – shivering, gritting her teeth against the pain. MYFANWY (V.O.) You're probably wondering why anyone would do such a thing. The answer is both simple and complicated. The simple answer is: because I knew it would be necessary. The complicated answer will take a little more time. She pats herself down, feeling for broken ribs, bruises – still staring at her body like it's something alien. There's something else in the coat pocket. She pulls out TWO CRUMPLED ENVELOPES. 1 Holds them up, squinting in the dim moonlight. -

SPOOKS: Fall of Babylon V. 1 Free Ebook

FREESPOOKS: FALL OF BABYLON V. 1 EBOOK Xavier Dorison,Fabien Nury,Christian Rossi | 56 pages | 16 Sep 2012 | CINEBOOK LTD | 9781849180993 | English | Ashford, United Kingdom Spooks ended five years ago – who's had the most successful post-show career? As the tenth and final series of Spooks opens, MI5 chief Harry Pearce is facing some complicated questions about the future. The Paperback of the The Fall of Babylon: SPOOKS, Vol. 1 by Xavier Dorison, Fabien Nury, Christine Rossi | at Barnes & Noble. 2 Dec Since Spooks ended, Peter starred as Jacob Marley in the BBC's from Last Tango in Halifax, Prisoners' Wives, Scott & Bailey, Babylon, Unforgotten and River. 7. Matthew played the show's lead from series 1 to 3, before Quinn was Proctor in Yaël Farber's stage version of Arthur Miller's The Crucible. The Fall of Babylon: SPOOKS, Vol. 1 The third series of the British spy drama television series Spooks began broadcasting on 11 The third series was seen by an average of million viewers, a decline in ratings from the Raymond Khoury felt that because the length of a Spooks episode is one and half times longer "MI-5 – Volume 3 DVD Information". SPOOKS 1 The Fall of Babylon Review. SAMPLE IMAGE. UK publisher / ISBN Cinebook - Volume No. 1. Release date 2 Dec Since Spooks ended, Peter starred as Jacob Marley in the BBC's from Last Tango in Halifax, Prisoners' Wives, Scott & Bailey, Babylon, Unforgotten and River. 7. Matthew played the show's lead from series 1 to 3, before Quinn was Proctor in Yaël Farber's stage version of Arthur Miller's The Crucible. -

Lionsgate Entertainment Corp

Lionsgate Entertainment Corp. Fiscal 2019 Second Quarter Earnings Call Thursday, November 08, 2018, 5:00 PM Eastern CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Jon Feltheimer - Chief Executive Officer Jimmy Barge - Chief Financial Officer Chris Albrecht – President & CEO Starz Joe Drake – Chairman, Motion Picture Group Kevin Beggs – Chairman, Television Group James Marsh – SVP & Head of Investor Relations 1 PRESENTATION Operator Ladies and gentlemen, thank you for standing by, and welcome to the Lionsgate Fiscal 2019 Second Quarter Earnings Call. At this time, all participants are in a listen-only mode. Later we will conduct a question-and-answer session. Instructions will be given at that time. If you should require assistance during the call, please press "*" then "0." And as a reminder, this conference is being recorded. I would now like to turn the conference over to our host James Marsh, Head of Investor Relations. Please go ahead sir. James Marsh Great, thanks Tanya, and good afternoon everyone. Thanks for joining us today for the Lionsgate Fiscal 2019 second quarter conference call. We'll begin with opening remarks from our CEO, Jon Feltheimer followed by remarks from our CFO, Jimmy Barge. After their remarks we'll open the call up for questions. Also joining us on the call today are Vice Chairman, Michael Burns, Starz’ President and COO, Chris Albrecht, Starz' COO, Jeff Hirsch, Starz' CFO, Scott Macdonald, Lionsgate COO, Brian Goldsmith, Chairman of the Motion Picture Group, Joe Drake, and Chairman of the TV Group, Kevin Beggs, COO of the TV Group, Laura Kennedy, and Chief Accounting Officer, Rick Prell. The matters discussed on this call include forward-looking statements, including those regarding the performance of future fiscal years. -

Rook I Project, Project Description

ROOK I PROJECT Project Description Submitted to: Saskatchewan Ministry of Environment Environmental Assessment and Stewardship Branch 3211 Albert Street, 4th Floor Regina, SK S4S 5W6 Attention: Ann Riemer Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) Uranium Mines and Mills Division 101 - 22nd Street East, Suite 520 Saskatoon, SK S7K 0E1 Attention: Richard Snider Submitted by: NexGen Energy Ltd. Operations Headquarters Suite 200, 475 – 2nd Ave S Saskatoon, SK S7K 1P4 April 2019 Rook I Project Project Description April 2019 Executive Summary The Rook I Project (Project) is a proposed new uranium mining and milling operation that is 100% owned by NexGen Energy Ltd. (NexGen). It is located adjacent to Patterson Lake in the southern Athabasca Basin in northern Saskatchewan approximately 155 km north of the town of La Loche, 80 km south of the former Cluff Lake Mine site (currently in decommissioning) and 640 km by air north west of Saskatoon. The mineral resource basis for the proposed Project is the Arrow deposit, a land-based, 100% basement hosted high grade uranium deposit. The current indicated Mineral Resource estimate for the Project totals 2.89 million tonnes at an average grade of 4.03% triuranium octoxide (U3O8), for a total of 116.4 million kg (256.6 million pounds) U3O8. (NexGen 2018). The Inferred Mineral Resource estimate is 91.7 Mlbs U3O8 in 4.84 million tonnes at an average grading of 0.86% U3O8. The Probable Mineral Reserve estimate is 234.1 Mlbs U3O8 contained in 3.43 million tonnes at an average grading of 3.09% U3O8. The proposed processing plant will be capable of producing up to 14 million kg (31 million lbs) of U3O8 per year with a projected mine life of 24 years based on current global resource estimates.