Hardy 1 Williamina Fleming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hidden History of Women in Astronomy

The Hidden History of Women in Astronomy Michael McEllin 1 Introduction What is the Sun made of? One hundred years ago our physical samples consisted of the Earth itself and a few meteorites, mostly rocky, with a few metallic and some rare `carbonaceous' examples containing volatiles. Fur- thermore, spectral lines in the Sun's light showed that many of the chemical elements discovered on the Earth were indeed also present on the Sun. Why would you believe that its composition was radically different to the Earth's, especially when the prevailing theories of Solar System origin had them be- ing formed from the same primeval stuff? There was even a just about tenable theory that the steady accretion of meteorites onto the Solar surface might release enough gravitational energy to keep it hot. What alternative was there? Sir Arthur Eddington had indeed speculated that Einstein's E = MC2 hinted at the possibility of extraordinary energy sources that might power the sun but we were still a decade away from understanding nuclear fusion reactions: Eddington's speculation may have been inspired but it was still vague speculation. Spectral lines were, in fact, still something of a mystery. We did not know why some spectral lines were so much more prominent than others or why some expected lines failed to appear at all. Until Bohr's model of the atom in 1913 we had no understanding at all of the origin of spectral lines, and there were clearly many missing bits of the puzzle. If you do not fully understand why lines look the way they do line how can you be certain you understand the conditions in which they form and relatively abundances of the contributing chemical elements? Atomic spectra began to be really understood only after 1925, when the new `Quantum Mechanics', in the form of Schr¨odinger'sequation, Heisen- berg's Matrix Mechanics and Dirac's relativistic theory of the electron re- placed the `Old Quantum Theory'. -

Transactions 1905

THE Royal Astronomical Society of Canada TRANSACTIONS FOR 1905 (INCLUDING SELECTED PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS) EDITED BY C. A CHANT. TORONTO: ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL PRINT, 1906. The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. THE Royal Astronomical Society of Canada TRANSACTIONS FOR 1905 (INCLUDING SELECTED PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS) EDITED BY C. A CHANT. TORONTO: ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL PRINT, 1906. TABLE OF CONTENTS. The Dominion Observatory, Ottawa (Frontispiece) List of Officers, Fellows and A ssociates..................... - - 3 Treasurer’s R eport.....................--------- 12 President’s Address and Summary of Work ------ 13 List of Papers and Lectures, 1905 - - - - ..................... 26 The Dominion Observatory at Ottawa - - W. F. King 27 Solar Spots and Magnetic Storms for 1904 Arthur Harvey 35 Stellar Legends of American Indians - - J. C. Hamilton 47 Personal Profit from Astronomical Study - R. Atkinson 51 The Eclipse Expedition to Labrador, August, 1905 A. T. DeLury 57 Gravity Determinations in Labrador - - Louis B. Stewart 70 Magnetic and Meteorological Observations at North-West River, Labrador - - - - R. F. Stupart 97 Plates and Filters for Monochromatic and Three-Color Photography of the Corona J. S. Plaskett 89 Photographing the Sun and Moon with a 5-inch Refracting Telescope . .......................... D. B. Marsh 108 The Astronomy of Tennyson - - - - John A. Paterson 112 Achievements of Nineteenth Century Astronomy , L. H. Graham 125 A Lunar Tide on Lake Huron - - - - W. J. Loudon 131 Contributions...............................................J. Miller Barr I. New Variable Stars - - - - - - - - - - - 141 II. The Variable Star ξ Bootis -------- 143 III. The Colors of Helium Stars - - - ..................... 144 IV. A New Problem in Solar Physics ------ 146 Stellar Classification ------ W. Balfour Musson 151 On the Possibility of Fife in Other Worlds A. -

Women Who Read the Stars Sue Nelson Delights in Dava Sobel’S Account of a Rare Band of Human Computers

Some of the Harvard Observatory ‘computers’ in 1925. Annie Jump Cannon is seated fifth from left; Cecilia Payne is at the drafting table. HISTORY Women who read the stars Sue Nelson delights in Dava Sobel’s account of a rare band of human computers. here are half a million photographic magnitude, on the as computers at Harvard, a practice unique plates in the Harvard College Observa- photographic plates to the university. Within five years, the num- tory collection, all unique. They date to and computing its ber of paid female computers, from a range Tthe mid-1880s, and each can display the light location in the sky. of backgrounds, had risen to 14. Their efforts from 50,000 stars. These fragments of the Pickering was espe- would be boosted by philanthropist Cath- cosmos furthered our understanding of the cially interested in erine Wolfe Bruce, who in 1889 donated Universe. They also reflect the dedication and variable stars, whose US$50,000 to the observatory, convinced intelligence of extraordinary women whose light would brighten that the introduction of photography and stories are more than astronomical history: and fade over a spe- spectroscopy would advance the field. ARCHIVES UNIV. HARVARD COURTESY they reveal lives of ambition, aspiration and cific period. These The Glass The Glass Universe concentrates on a few of brilliance. It takes a talented writer to inter- fluctuations, captured Universe: How the Harvard computers. Williamina Fleming, weave professional achievement with per- on the plates, required the Ladies of a Scottish school teacher, arrived at the obser- sonal insight. By the time I finished The Glass constant observation, the Harvard vatory in 1879, pregnant and abandoned by Universe, Dava Sobel’s wonderful, meticulous but he couldn’t afford Observatory Took her husband. -

At the Harvard Observatory

Book Reviews 117 gravitational wave physicists, all of whom are members of an international group of over a thousand scientists engaged with the detection apparatus at two widely separated sites, one in Livingston, Louisiana and the other in Hanford, Washington. The emails research- ers in the collaboration exchanged and the queries Collins sent to the physicists who acted for him as “key informants” provide the bulk of the material for Collins’ “real- time” observations of this discovery in the making. At times, Collins finds the community of researchers exasperating and wrong-headed in their, in his view, overly secretive attitudes to their results. But Collins is not a detached witness of the events he describes and analyses. Instead, he is overall a highly enthusias- tic fan of the gravitational wave community. Collins has not sought out for Gravity’s Kiss the kinds of evidence one might have expected a historian to have pursued. Gravity’s Kiss, however, should be read on its terms. It is a work of reportage from an “embedded” sociologist of science with long experience of, and valuable connections in, the gravitational wave community. Along the way, he offers sharp insights into the work- ing of these scientists. Collins proves to be an excellent guide to the operations of a “Big Science” collaboration and the intense scrutiny of, and complicated negotiations around, the “[v]ery interesting event on ER8.” Robert W. Smith University of Alberta [email protected] “Girl-Hours” at the Harvard Observatory The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars. -

Study Guide Table of Contents

STUDY GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS DIRECTOR’S NOTE 2 THE PLAYWRIGHT 6 HENRIETTA LEAVITT 7 ANNIE JUMP CANNON 9 WILLIAMINA FLEMING 10 EDWARD PICKERING 11 THE LIFE OF A COMPUTER AT HCO 12 STAR SPANKING! 13 TELESCOPES AND THE GREAT REFRACTOR AT HCO 14 GLOSSARY OF ASTRONOMICAL TERMS 15 AN ASTRONOMICAL GLOSSARY 17 THE CAST 18 TIMELINE 20 WHEN I HEARD THE LEARNED ASTRONOMER 21 AUDIENCE ETIQUETTE 22 STUDENT EVALUATION 23 TEACHER EVALUATION 24 2 3 4 5 THE PLAYWRIGHT LAUREN GUNDERSON is the most produced living playwright in America, the winner of the Lanford Wilson Award and the Steinberg/ATCA New Play Award, a finalist for the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize and John Gassner Award for Playwriting, and a recipient of the Mellon Foundation’s 3-Year Residency with Marin Theatre Co. She studied Southern Literature and Drama at Emory University, and Dramatic Writing at NYU’s Tisch School where she was a Reynolds Fellow in Social Entrepreneurship. Her work has been commissioned, produced and developed at companies across the US including the Denver Center (The Book Of Will), South Coast Rep (Emilie, Silent Sky), The Kennedy Center (The Amazing Adventures Of Dr. Wonderful And Her Dog!), the O’Neill Theatre Center, Berkeley Rep, Shotgun Players, TheatreWorks, Crowded Fire, San Francisco Playhouse, Marin Theatre, Synchronicity, Olney Theatre, Geva, and more. Her work is published by Dramatists Play Service (Silent Sky, Bauer), Playscripts (I and You; Exit, Pursued by a Bear; and Toil and Trouble), and Samuel French (Emilie). She is a Playwright in Residence at The Playwrights Foundation, and a proud Dramatists Guild member. -

Women in Astronomy: an Introductory Resource Guide

Women in Astronomy: An Introductory Resource Guide by Andrew Fraknoi (Fromm Institute, University of San Francisco) [April 2019] © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. For permission to use, or to suggest additional materials, please contact the author at e-mail: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu This guide to non-technical English-language materials is not meant to be a comprehensive or scholarly introduction to the complex topic of the role of women in astronomy. It is simply a resource for educators and students who wish to begin exploring the challenges and triumphs of women of the past and present. It’s also an opportunity to get to know the lives and work of some of the key women who have overcome prejudice and exclusion to make significant contributions to our field. We only include a representative selection of living women astronomers about whom non-technical material at the level of beginning astronomy students is easily available. Lack of inclusion in this introductory list is not meant to suggest any less importance. We also don’t include Wikipedia articles, although those are sometimes a good place for students to begin. Suggestions for additional non-technical listings are most welcome. Vera Rubin Annie Cannon & Henrietta Leavitt Maria Mitchell Cecilia Payne ______________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents: 1. Written Resources on the History of Women in Astronomy 2. Written Resources on Issues Women Face 3. Web Resources on the History of Women in Astronomy 4. Web Resources on Issues Women Face 5. Material on Some Specific Women Astronomers of the Past: Annie Cannon Margaret Huggins Nancy Roman Agnes Clerke Henrietta Leavitt Vera Rubin Williamina Fleming Antonia Maury Charlotte Moore Sitterly Caroline Herschel Maria Mitchell Mary Somerville Dorrit Hoffleit Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin Beatrice Tinsley Helen Sawyer Hogg Dorothea Klumpke Roberts 6. -

Spectroscopy: History 1885-1927

SPECTROSCOPY: HISTORY 1885-1927 Harvard Observatory director Edward Charles Pickering hired over 80 women as technicians to perform scientific and mathematical calculations by hand. They became known as the “Harvard Computers”. This was more than 40 years before women gained the right to vote. They received global recognition for their contributions that changed the science of astronomy. Due to their accomplishments, they paved the way for other women to work in scientific and engineering careers. WHAT DID THEY DO: They studied glass photographic plates of stellar spectra created by using a spectroscope. Using a simple magnifying glass, they compared Credit: Secrets of the Universe: Space Pioneer, card 48 positions of stars between plates, calculating the temperature and motion of the stars. WHO WERE THEY: They measured the relative brightness of stars and analyzed spectra Some had college degrees, others received on-the job-training. to determine the properties of celestial objects. A few were permitted to receive graduate degrees for their accomplishments. These plates were gathered from observatories in Peru, South Africa, New Zealand, Chile and throughout the USA They worked for 25 cents an hour, six days a week in a small cramped library. Many of these women received numerous awards and honors for Harvard University Plates Stacks Digitization Project their contributions. Noteable among them were: Harvard College Observatory’s Plate Collection (also known as the Plate Stacks) is the world’s largest archive of stellar glass plate negatives. Taken between the mid 1880s and 1989 (with a gap 1953-68) the WILLIAMINA FLEMING (1857-1911) - developed the Pickering- collection grew to 500,000 and is currently being digitized. -

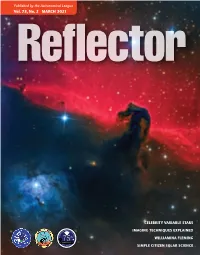

Reflector March 2021 Final Pages.Pdf

Published by the Astronomical League Vol. 73, No. 2 MARCH 2021 CELEBRITY VARIABLE STARS IMAGING TECHNIQUES EXPLAINED 75th WILLIAMINA FLEMING SIMPLE CITIZEN SOLAR SCIENCE AN EMPLOYEE-OWNED COMPANY NEW FREE SHIPPING on order of $75 or more & INSTALLMENT BILLING on orders over $350 PRODUCTS Standard Shipping. Some exclusions apply. Exclusions apply. Orion® StarShoot™ Mini 6.3mp Imaging Cameras (sold separately) Orion® StarShoot™ G26 APS-C Orion® GiantView™ BT-100 ED Orion® EON 115mm ED Triplet Awesome Autoguider Pro Refractor Color #51883 $400 Color Imaging Camera 90-degree Binocular Telescope Apochromatic Refractor Telescope Telescope Package Mono #51884 $430 #51458 $1,800 #51878 $2,600 #10285 $1,500 #20716 $600 Trust 2019 Proven reputation for Orion® U-Mount innovation, dependability and and Paragon Plus service… for over 45 years! XHD Package #22115 $600 Superior Value Orion® StarShoot™ Deep Space High quality products at Orion® StarShoot™ G21 Deep Space Imaging Cameras (sold separately) Orion® 120mm Guide Scope Rings affordable prices Color Imaging Camera G10 Color #51452 $1,200 with Dual-Width Clamps #54290 $950 G16 Mono #51457 $1,300 #5442 $130 Wide Selection Extensive assortment of award winning Orion brand 2019 products and solutions Customer Support Orion products are also available through select Orion® MagneticDobsonian authorized dealers able to Counterweights offer professional advice and Orion® Premium Linear Orion® EON 130mm ED Triplet Orion® 2x54 Ultra Wide Angle 1-Pound #7006 $25 Binoculars post-purchase support BinoViewer -

Women of Astronomy

WOMEN OF ASTRONOMY AND A TIMELINE OF EVENTS… Time line of Astronomy • 2350 B.C. – EnHeduanna (ornament of heaven) – • Chief Astronomer Priestess of the Moon Goddess of the City in Babylonia. • Movement of the Stars were used to create Calendars • 2000 B.C. - According to legend, two Chinese astronomers are executed for not predicting an eclipse. • 129 B.C. - Hipparchos completes the first catalog of the stars, and invented stellar magnitude (still in use today!) • 150 A.D. - Claudius Ptolemy publishes his theory of the Earth- centered universe. • 350 A.D – Hypatia of Alexandria – First woman Astronomer • Hypatia of Alexandria Born approximately in 350 A.D. • Accomplished mathematician, inventor, & philosopher of Plato and Aristotle • Designed astronomical instruments, such as the astrolabe and the planesphere. The first star chart to have the name An early astrolabe was invented in "planisphere" was made in 1624 by 150 BC and is often attributed to Jacob Bartsch. Son of Johannes Hipparchus Kepler, who solved planetary motion. Time line of Astronomy • 970 - al-Sufi, a Persian Astronomer prepares catalog of over 1,000 stars. • 1420 Ulugh-Beg, prince of Turkestan, builds a great observatory and prepares tables of planet and stars • 1543 While on his deathbed, Copernicus publishes his theory that planets orbit around the sun. • 1609 Galileo discovers craters on Earth’s moon, the moons of Jupiter, the turning of the sun, and the presence of innumerable stars in the Milky Way with a telescope that he built. • 1666 Isaac Newton begins his work on the theory of universal gravitation. • 1671 Newton demonstrates his invention, the reflecting telescope. -

Measure by Measure They Touched the Heaven

2019 IMEKO TC-4 International Conference on Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Florence, Italy, December 4-6, 2019 Measure by Measure they touched the heaven Luisa Spairani – Gruppo Astrofili Eporediesi – C.so Vercelli 444 10015 Ivrea – [email protected] Abstract – The measure of distances is a recurring theme in astrophysics. The interpretation of the light Distances in astrophysics are notoriously difficult to coming from a luminous object in the sky can be very calculate. It is possible to use geometric methods to different depending on the distance of the object. Two determine the objects that are in the proximity of the solar stars or galaxies may have a different real brightness, system, we say within a distance of about 150 light-years although they may look similar. The correct measures from us. Beyond it is impossible to use any simple came by women computers a century ago. Special method to calculate distances. And this was the situation mention to Williamina Fleming who supervised an in astronomical research at the beginning of the last observatory for 30 years working on the first system to century. Many new objects had been discovered, but classify stars by spectrum. Antonia Maury helped locate without knowing their distances, it was impossible to put the first double star and developed her classification them in any stellar systems model. At that time, before system. Henrietta Leavitt found a law to determine 1900, it was not known that we live in a galaxy called the stellar distances. The most famous of the Harvard Milky Way, and there are other galaxies. -

Women in Astronomy at Harvard College Observatory

Discussion Question Answers Strategies and Compromises: Women in Astronomy at Harvard College Observatory 1. What were the differences between the roles of the four women mentioned in the article? - Williamina Fleming started out simply copying and computing, but worked her way up to supervising the other women and classifying solar spectra. - Antonia Maury also classified stellar spectra, but she did so with an advanced system of her own design. The director of the observatory, Pickering, did not like her system and so she left the observatory. - Annie Jump Cannon continued the spectra work of Maury, but used the standard system. She worked for 45 years doing classification work extremely quickly and consistently. - Henrietta Leavitt studied variable stars at first, identifying thousands of new ones. She also did the research assigned to her, which related to determining how stars appeared using different photographic techniques. 2. What are the differences between their attitudes towards the roles they were assigned? - Fleming accepted any work that was asked of her, but expanded the role of women’s work by her competence in accomplishing the tasks. She was privately bitter about the low pay and status of her work. - Maury thought that her intellectual contributions were worthy of credit and regard. She insisted on being recognized in the Observatory’s publications, and she fought for her system, which was based on star’s “natural relations” to be used. However, she did not succeed in getting the system used and so left the observatory. - Cannon did not mind the role she was assigned. She did it so quickly and well she eventually gained recognition and an honorary doctorate for he accomplishments. -

The Canadian Astronomical Handbook for 1908

T h e Ca n a d i a n A stronomical H a n d b o o k FOR 1908 PUBLISHED BY THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA E d i t e d b y C. A. CHANT SECOND YEAR OF PUBLICATION TORONTO 198 C o l l e g e S t r e e t P r i n t e d f o r t h e S o c i e t y 1907 T h e Ca n a d i a n A stronomical H a n d b o o k FOR 1908 T h e Ca n a d ia n A stronomical H a n d b o o k FOR 1908 PUBLISHED BY THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA E d i t e d b y C. A. CHANT SECOND YEAR OF PUBLICATION TORONTO 198 C o l l e g e S t r e e t P r i n t e d f o r t h e S o c i e t y 1907 CONTENTS Page Preface.......................................................................... 5 Symbols and Abbreviations ....................................... 7 Chronological Eras and Cycles.................................... 8 Fixed and Movable Festivals, Etc.............................. 8 Standard Time..................................................... 9 Calendar for the Year . 9 to 33 Geographical Positions of Points in Canada............. 34 Magnetic Elements for Toronto, 1901-1906............... 36 The Solar System : Eclipses of Sun and Moon................................... 37 Principal Elements of the Solar System............ 39 Satellites of the Solar System............................. 40 The Planets in 1908, with Maps......................... 41 Meridian Passage of Five Planets..............................