'Til Morning: the Reception of Jm Barrie's Peter Pan A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Kaleidoscope

The faculty advisors wish to give special recognition and thanks to these individuals who also gave of their time and energy to make this edition of the Kaleidoscope possible: Lauren Courtney, Jakob Plotts, and Tracy Snowman. Thank you! 2 Kaleidoscope Journal of Art & Literature -Editor- James Grove -Assistant Editors- Brie Coder Alexa Dailey Georgia Meagher Trista Miller Cameron Phillips -Faculty Advisors- Michael Maher Becca Werland -Cover Art- Brandy Wise 3 Alexa Dailey-17, 25 Alyssa Brown-28 Amber Burnett-8 Annalea Forrest-9, 11, 16, 18, 24 Aubrey Foust-6, 14, 20, 31 Brandy Wise-Cover Brie Coder-29 Cecilia Carrillo-12, 18 Edward Johnson-5, 9, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30 Frances G. Tate-32 Georgia Meagher-13 Jacqueline Westin-6,10, 12, 20, 26 Jakob Plotts-3, 5, 8, 21 James Grove-21, 32 Jed Vaughn-11 Lafe Richardson-10, 19 An Artist’s Still Life Paula Cortes-4 Jakob Plotts Sheretta S Miller-7, 15, 22 4 Letter from the Editor Life is filled with a variety of people; some are good and others bad. We have athletes, scholars, theatre progressives, metal heads, and far too many more to write down in the little space I have. The point is that life is filled with different walks of life, and perhaps that’s what I en- joy most about the Kaleidoscope. Within these pages, you, dear reader, will find people who’ve gained and lost, found joy and pain. You’ll find works of the sur- real, and still ones of reality. I give thanks to those who helped piece together the many to present something whole, for that is the heart of the Kaleidoscope. -

The New Yorker

Kindle Edition, 2015 © The New Yorker COMMENT SEARCH AND RESCUE BY PHILIP GOUREVITCH On the evening of May 22, 1988, a hundred and ten Vietnamese men, women, and children huddled aboard a leaky forty-five-foot junk bound for Malaysia. For the price of an ounce of gold each—the traffickers’ fee for orchestrating the escape—they became boat people, joining the million or so others who had taken their chances on the South China Sea to flee Vietnam after the Communist takeover. No one knows how many of them died, but estimates rose as high as one in three. The group on the junk were told that their voyage would take four or five days, but on the third day the engine quit working. For the next two weeks, they drifted, while dozens of ships passed them by. They ran out of food and potable water, and some of them died. Then an American warship appeared, the U.S.S. Dubuque, under the command of Captain Alexander Balian, who stopped to inspect the boat and to give its occupants tinned meat, water, and a map. The rations didn’t last long. The nearest land was the Philippines, more than two hundred miles away, and it took eighteen days to get there. By then, only fifty-two of the boat people were left alive to tell how they had made it—by eating their dead shipmates. It was an extraordinary story, and it had an extraordinary consequence: Captain Balian, a much decorated Vietnam War veteran, was relieved of his command and court- martialled, for failing to offer adequate assistance to the passengers. -

The Success and Ambiguity of Young Adult Literature: Merging Literary Modes in Contemporary British Fiction Virginie Douglas

The Success and Ambiguity of Young Adult Literature: Merging Literary Modes in Contemporary British Fiction Virginie Douglas To cite this version: Virginie Douglas. The Success and Ambiguity of Young Adult Literature: Merging Literary Modes in Contemporary British Fiction. Publije, Le Mans Université, 2018. hal-02059857 HAL Id: hal-02059857 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02059857 Submitted on 7 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Abstract: This paper focuses on novels addressed to that category of older teenagers called “young adults”, a particularly successful category that is traditionally regarded as a subpart of children’s literature and yet terminologically insists on overriding the adult/child divide by blurring the frontier between adulthood and childhood and focusing on the transition from one state to the other. In Britain, YA fiction has developed extensively in the last four decades and I wish to concentrate on what this literary emergence and evolution has entailed since the beginning of the 21st century, especially from the point of view of genre and narrative mode. I will examine the cases of recognized—although sometimes controversial—authors, arguing that although British YA fiction is deeply indebted to and anchored in the pioneering American tradition, which proclaimed the end of the Romantic child as well as that of the compulsory happy ending of the children’s book, there seems to be a recent trend which consists in alleviating the roughness, the straightforwardness of realism thanks to elements or touches of fantasy. -

Facultad De Filosofía Y Letras Título Del

CURSO 2018-2019 Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Grado en Periodismo Título del TFG LA PERSONALIDAD DEL PETER PAN ORIGINAL EN LA LITERATURA Y LA CONCEPCIÓN SIMPLIFICADA DEL PERSONAJE EN EL IMAGINARIO COLECTIVO Alumno: Juan Eguren Paredes Tutora: Nereida López Vidales 1 2 RESUMEN Arrastrados por la cultura multimedia, generaciones enteras han disfrutado y mitificado iconos de la gran pantalla sin conocer las verdaderas intenciones de su autor original. Peter Pan es un ejemplo de ello y su personalidad fue fruto de su época, en el Londres de principios del siglo XX. Sus rasgos influenciados por personajes mitológicos y experiencias de su creador, James M. Barrie, se perdieron con la adaptación que lo hizo mundialmente famoso. Disney le dio el éxito y blanqueó aspectos de Pan que, aun así, han trascendido al imaginario colectivo llegando a considerar a “Peter Pan” como un adulto que no quiere afrontar responsabilidades. Este estudio pretende analizar la personalidad escogida por Barrie así como sus diferentes obras con él como protagonista y el poso cultural restante a día de hoy pasando por el “síndrome” tan frecuentemente mencionado. Esto supondrá no sólo el análisis de las tres obras escritas por el escocés que le mencionan explícitamente, sino también la contextualización de Neverland o El País de Nunca Jamás, la descripción de un “Peter Pan” hoy en día, tal y como lo presentan estudios en psicología, y un resumen final como comparativa de las diferentes cualidades atribuidas al personaje. Además, se incluirán algunas referencias a alguna adaptación cinematográfica y la historia que llevó a Barrie al diseño del personaje tal y como se puede disfrutar en su literatura. -

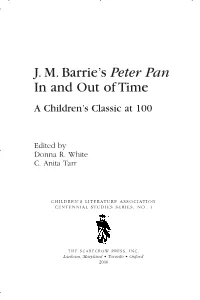

J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan in and out of Time

06-063 01 Front.qxd 3/1/06 7:36 AM Page iii J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan In and Out of Time A Children’s Classic at 100 Edited by Donna R. White C. Anita Tarr CHILDREN’S LITERATURE ASSOCIATION CENTENNIAL STUDIES SERIES, NO. 4 THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Oxford 2006 06-063 01 Front.qxd 3/1/06 7:36 AM Page v Contents Introduction vii Donna R. White and C. Anita Tarr Part I: In His Own Time 1 Child-Hating: Peter Pan in the Context of Victorian Hatred 3 Karen Coats 2 The Time of His Life: Peter Pan and the Decadent Nineties 23 Paul Fox 3 Babes in Boy-Land: J. M. Barrie and the Edwardian Girl 47 Christine Roth 4 James Barrie’s Pirates: Peter Pan’s Place in Pirate History and Lore 69 Jill P. May 5 More Darkly down the Left Arm: The Duplicity of Fairyland in the Plays of J. M. Barrie 79 Kayla McKinney Wiggins Part II: In and Out of Time—Peter Pan in America 6 Problematizing Piccaninnies, or How J. M. Barrie Uses Graphemes to Counter Racism in Peter Pan 107 Clay Kinchen Smith v 06-063 01 Front.qxd 3/1/06 7:36 AM Page vi vi Contents 7 The Birth of a Lost Boy: Traces of J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Willa Cather’s The Professor’s House 127 Rosanna West Walker Part III: Timelessness and Timeliness of Peter Pan 8 The Pang of Stone Words 155 Irene Hsiao 9 Playing in Neverland: Peter Pan Video Game Revisions 173 Cathlena Martin and Laurie Taylor 10 The Riddle of His Being: An Exploration of Peter Pan’s Perpetually Altering State 195 Karen McGavock 11 Getting Peter’s Goat: Hybridity, Androgyny, and Terror in Peter Pan 217 Carrie Wasinger 12 Peter Pan, Pullman, and Potter: Anxieties of Growing Up 237 John Pennington 13 The Blot of Peter Pan 263 David Rudd Part IV: Women’s Time 14 The Kiss: Female Sexuality and Power in J. -

Degree Project Bachelor’S Degree Fantasy Fiction from a Gender Perspective

Degree Project Bachelor’s Degree Fantasy Fiction from a Gender Perspective A Study of Gender Differences in Peter Pan and Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone Author: Rebecka Ivarsson Supervisor: Billy Gray Examiner: David Gray Subject/main field of study: English Literature Course code: EN2028 Credits: 15 hp Date of examination: 7th January, 2019 At Dalarna University it is possible to publish the student thesis in full text in DiVA. The publishing is open access, which means the work will be freely accessible to read and download on the internet. This will significantly increase the dissemination and visibility of the student thesis. Open access is becoming the standard route for spreading scientific and academic information on the internet. Dalarna University recommends that both researchers as well as students publish their work open access. I give my/we give our consent for full text publishing (freely accessible on the internet, open access): Yes ☒ No ☐ Dalarna University – SE-791 88 Falun – Phone +4623-77 80 00 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 Feminist Literary Theory ........................................................................................................... 8 The Domestic ........................................................................................................................... 11 Knowledge .............................................................................................................................. -

Peter Pan As a Trickster Figure 2013

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Teaching English Language and Literature for Secondary Schools Bc. Eva Valentová The Betwixt and Between: Peter Pan as a Trickster Figure Master‘s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. Michael Matthew Kaylor, Ph.D. 2013 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Eva Valentová 2 I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Michael Matthew Kaylor, Ph.D., for his kind help and valuable advice. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 5 1 In Search of the True Trickster .................................................................................. 7 2 The Betwixt and Between: Peter Pan as a Trickster Figure .................................... 26 2.1 J. M. Barrie: A Boy Trapped in a Man‘s Body ................................................ 28 2.2 Mythological Origins of Peter Pan ................................................................... 35 2.3 Victorian Child: An Angel or an Animal? ....................................................... 47 2.4 Neverland: The Place where Dreams Come True ............................................ 67 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 73 Appendix ........................................................................................................................ -

Welcome to Peter Pan Ward

Welcome to Peter Pan Ward Information for families Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust This leaflet explains about the facilities available on Peter Pan Ward and what to expect when your child comes to the ward. About the ward size bed, he or she may need to stay on Peter Pan Ward is a surgical ward for another ward. Peter Pan Ward is fully children having ear, nose and throat accessible to disabled children and holds (ENT) surgery, maxillofacial (jaw and relevant equipment, such as hoists and facial) surgery, cleft lip and/or palate sliding boards. The ward has a disabled repair, dental surgery, plastic surgery or toilet and bathing facilities. There is also having cochlear implants fitted. Children of another bathroom on the ward that can any age (up to and including adolescence) be used by children and their parents. stay on Peter Pan Ward, although the The ward is arranged in two wings and majority are under five years’ old. there are 18 beds on the ward overall. The ward has a full complement of These are arranged in two bays of four nursing staff and the clinical nurse and five beds, a nursery holding three specialists for tracheostomies and ENT cots and six side rooms. Your child will surgery are based on Peter Pan Ward. be nursed in a bay as the side rooms are Other members of the team include our usually allocated to children who either play specialist, health care assistants, have an infection or who have to be admissions and administration staff. -

ADHD in the Shadows

Complex, Comorbid, Contraindicated, and Confusing Patients Bill Dodson, M.D. Private Practice [email protected] Roberto Olivardia, Ph.D. Harvard Medical School [email protected] ADHD in the Shadows • Importance of comorbid disorders • ADHD often not even assessed at intake • ADHD vastly underdiagnosed, especially in adults • Even when ADHD is known it is clinically underappreciated Why did we think that ADHD went away in adolescence? • True hyperactivity was either never present or diminishes to mere restlessness after puberty. • People learn compensations (but is this remission?). • People with ADHD stop trying to do things in which they know they will fail. • People with ADHD drop out of society or end up in jail and are no longer available for studies. • “Helicopter Moms” compensate for their ADHD children, adolescents, and adults. Recognition and Diagnosis • Most clinicians who treat adults never consider the possibility of ADHD. • Less than 8% of psychiatrists and less than 3% of physicians who treat adults have any training in ADHD. Most report that they do not feel confident with either the diagnosis or treatment. (Eli Lilly Marketing Research) • ADHD in adults is an “orphan diagnosis” ignored by the APA, the DSM, and training programs 38 years after it was officially recognized to persist lifelong. It is Not Adequate to Merely Extend Childhood Criteria • Some symptoms diminish with age (e.g., hyperactivity becomes restlessness). • Some new symptoms emerge (sleep disturbances, reactive mood lability). • Life demands get harder. Adults with ADHD must do things that a child doesn’t…Love, Work, and raise kids (half of whom will have ADHD). -

Fantastical Worlds and the Act of Reading in Peter and Wendy, the Chronicles of Narnia, and Harry Potter

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Master’s Theses Student Theses Spring 2021 Fantastical Worlds and the Act of Reading in Peter and Wendy, The Chronicles of Narnia, and Harry Potter Grace Monroe Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/masters_theses Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Monroe, Grace, "Fantastical Worlds and the Act of Reading in Peter and Wendy, The Chronicles of Narnia, and Harry Potter" (2021). Master’s Theses. 247. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/masters_theses/247 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master’s Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I, Grace Monroe, do grant permission for my thesis to be copied. FANTASTICAL WORLDS AND THE ACT OF READING IN PETER AND WENDY, THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA, AND HARRY POTTER by Grace Rebecca Monroe (A Thesis) Presented to the Faculty of Bucknell University In Partial Fulfillments of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English : Virginia Zimmerman : Anthony Stewart _____May 2021____________ (Date: month and Year) Next moment he was standing erect on the rock again, with that smile on his face and a drum beating within him. It was saying, “To die would be an awfully big adventure.” J.M. Barrie, Peter and Wendy Acknowledgements I would like to thank the many people who have been instrumental in my completion of this project. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Legends in a Snowfall

LEGENDS IN A SNOWFALL By Claudia Haas Performance Rights It is an infringement of the federal copyright law to copy or reproduce this script in any manner or to perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co., Inc. Call the publisher for additional scripts and further licensing information. The author’s name must appear on all programs and advertising with the notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Company.” PUBLISHED BY ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING COMPANY www.histage.com © 1999 by Claudia Haas Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing http://www.histage.com/playdetails.asp?PID=1605 Legends in a Snowfall - 2 - STORY OF THE PLAY Winter tales from around the world come together to celebrate the joys and wonders of this dark and cold season. Ellisandra, a weather spirit who hopes to become Frost Queen, takes Faith, a frazzled mother, on a journey of imagination. They first meet the Snow Maiden, a beautiful woman who can only live during winter, in a legend from Russia. Tempesta, a stormy weather spirit who also seeks the title of Frost Queen, follows with her own Native American tale from Minnesota. It’s about a young poet at odds with a warrior lifestyle and his encounter with a Great White Bear. The tales are threaded together with an Eskimo story about the Northern Lights. The characters are a wonderful mix of humans, spirits, mischievous snowflakes and sparkling northern lights. Suggested music adds a grace note to creating the perfect winter solstice program. This play promises winter enchantment for all.