In Rural China, the Highest Compliment You Can Get Is Not That You're

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World at the Time of Messel: Conference Volume

T. Lehmann & S.F.K. Schaal (eds) The World at the Time of Messel - Conference Volume Time at the The World The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 2011 Frankfurt am Main, 15th - 19th November 2011 ISBN 978-3-929907-86-5 Conference Volume SENCKENBERG Gesellschaft für Naturforschung THOMAS LEHMANN & STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL (eds) The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference Frankfurt am Main, 15th – 19th November 2011 Conference Volume Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung IMPRINT The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Conference Volume Publisher PROF. DR. DR. H.C. VOLKER MOSBRUGGER Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Editors DR. THOMAS LEHMANN & DR. STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected]; [email protected] Language editors JOSEPH E.B. HOGAN & DR. KRISTER T. SMITH Layout JULIANE EBERHARDT & ANIKA VOGEL Cover Illustration EVELINE JUNQUEIRA Print Rhein-Main-Geschäftsdrucke, Hofheim-Wallau, Germany Citation LEHMANN, T. & SCHAAL, S.F.K. (eds) (2011). The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates. 22nd International Senckenberg Conference. 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main. Conference Volume. Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, Frankfurt am Main. pp. 203. -

Genome Sequence of the Basal Haplorrhine Primate Tarsius Syrichta Reveals Unusual Insertions Patrick Minx Washington University School of Medicine in St

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2016 Genome sequence of the basal haplorrhine primate Tarsius syrichta reveals unusual insertions Patrick Minx Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Michael J. Montague Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Richard K. Wilson Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Wesley C. Warren Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis et al Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Recommended Citation Minx, Patrick; Montague, Michael J.; Wilson, Richard K.; Warren, Wesley C.; and et al, ,"Genome sequence of the basal haplorrhine primate Tarsius syrichta reveals unusual insertions." Nature Communications.7,. 12997. (2016). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/5389 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE Received 29 Oct 2015 | Accepted 17 Aug 2016 | Published 6 Oct 2016 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms12997 OPEN Genome sequence of the basal haplorrhine primate Tarsius syrichta reveals unusual insertions Ju¨rgen Schmitz1,2, Angela Noll1,2,3, Carsten A. Raabe1,4, Gennady Churakov1,5, Reinhard Voss6, Martin Kiefmann1, Timofey Rozhdestvensky1,7,Ju¨rgen Brosius1,4, Robert Baertsch8, Hiram Clawson8, Christian Roos3, Aleksey Zimin9, Patrick Minx10, Michael J. Montague10, Richard K. Wilson10 & Wesley C. Warren10 Tarsiers are phylogenetically located between the most basal strepsirrhines and the most derived anthropoid primates. While they share morphological features with both groups, they also possess uncommon primate characteristics, rendering their evolutionary history somewhat obscure. -

Genome Sequence of the Basal Haplorrhine Primate Tarsius Syrichta Reveals Unusual Insertions

ARTICLE Received 29 Oct 2015 | Accepted 17 Aug 2016 | Published 6 Oct 2016 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms12997 OPEN Genome sequence of the basal haplorrhine primate Tarsius syrichta reveals unusual insertions Ju¨rgen Schmitz1,2, Angela Noll1,2,3, Carsten A. Raabe1,4, Gennady Churakov1,5, Reinhard Voss6, Martin Kiefmann1, Timofey Rozhdestvensky1,7,Ju¨rgen Brosius1,4, Robert Baertsch8, Hiram Clawson8, Christian Roos3, Aleksey Zimin9, Patrick Minx10, Michael J. Montague10, Richard K. Wilson10 & Wesley C. Warren10 Tarsiers are phylogenetically located between the most basal strepsirrhines and the most derived anthropoid primates. While they share morphological features with both groups, they also possess uncommon primate characteristics, rendering their evolutionary history somewhat obscure. To investigate the molecular basis of such attributes, we present here a new genome assembly of the Philippine tarsier (Tarsius syrichta), and provide extended analyses of the genome and detailed history of transposable element insertion events. We describe the silencing of Alu monomers on the lineage leading to anthropoids, and recognize an unexpected abundance of long terminal repeat-derived and LINE1-mobilized transposed elements (Tarsius interspersed elements; TINEs). For the first time in mammals, we identify a complete mitochondrial genome insertion within the nuclear genome, then reveal tarsier-specific, positive gene selection and posit population size changes over time. The genomic resources and analyses presented here will aid efforts to more fully understand the ancient characteristics of primate genomes. 1 Institute of Experimental Pathology, University of Mu¨nster, 48149 Mu¨nster, Germany. 2 Mu¨nster Graduate School of Evolution, University of Mu¨nster, 48149 Mu¨nster, Germany. 3 Primate Genetics Laboratory, German Primate Center, Leibniz Institute for Primate Research, 37077 Go¨ttingen, Germany. -

8. Primate Evolution

8. Primate Evolution Jonathan M. G. Perry, Ph.D., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Stephanie L. Canington, B.A., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Learning Objectives • Understand the major trends in primate evolution from the origin of primates to the origin of our own species • Learn about primate adaptations and how they characterize major primate groups • Discuss the kinds of evidence that anthropologists use to find out how extinct primates are related to each other and to living primates • Recognize how the changing geography and climate of Earth have influenced where and when primates have thrived or gone extinct The first fifty million years of primate evolution was a series of adaptive radiations leading to the diversification of the earliest lemurs, monkeys, and apes. The primate story begins in the canopy and understory of conifer-dominated forests, with our small, furtive ancestors subsisting at night, beneath the notice of day-active dinosaurs. From the archaic plesiadapiforms (archaic primates) to the earliest groups of true primates (euprimates), the origin of our own order is characterized by the struggle for new food sources and microhabitats in the arboreal setting. Climate change forced major extinctions as the northern continents became increasingly dry, cold, and seasonal and as tropical rainforests gave way to deciduous forests, woodlands, and eventually grasslands. Lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers—once diverse groups containing many species—became rare, except for lemurs in Madagascar where there were no anthropoid competitors and perhaps few predators. Meanwhile, anthropoids (monkeys and apes) emerged in the Old World, then dispersed across parts of the northern hemisphere, Africa, and ultimately South America. -

Pesola Supports Research and Conservation Project of the Philippine Tarsier

PESOLA SUPPORTS RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION PROJECT OF THE PHILIPPINE TARSIER The Philippine tarsier (Tarsius syrichta) is one of the smallest primates in the world and inhabits only several islands in the Philippines. This species decreases in numbers due to habitat degradation, especially logging and illegal hunting. The latter is the biggest threat to tarsiers, because tarsiers are faunal symbol of the Philippines, especially of Bohol Island, and thus became a tourist spot. Local people try to meet the demand of growing tourist flow by establishment of tarsiers’ display facilities. Unfortunately, the Philippine tarsier is one of the animal species which is extremely difficult to keep in captivity. Despite attempts being made in the past in Western facilities, the breeding colony of this species has not been established. This is due to the lifestyle of the tarsiers which are nocturnal, stress prone and completely faunivorous, which means they eat only live animals, mostly insects. To provide necessary conditions for them in captivity is very difficult, so the Philippine tarsiers did not breed successfully. The Tarsius Project: Research and Conservation of the Philippine tarsier (Tarsius syrichta) is located in Suabyon, Bilar, Bohol in the Philippines and tries to combat the extinction of these incredible creatures and secure its preservation through different activities, especially by conducting research, educating of local people, sustainable eco-tourism activities, implementation of livelihood projects for local villagers and welfare of captive tarsiers. The latter aims in establishment of captive breeding colony and development of husbandry guidelines, which could be used by local facilities, diminishing the need for replacement of captive tarsiers with the wild counterparts, if they breed. -

Fossil Primates

AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education Page 1 of 16 www.accessscience.com Fossil primates Contributed by: Eric Delson Publication year: 2014 Extinct members of the order of mammals to which humans belong. All current classifications divide the living primates into two major groups (suborders): the Strepsirhini or “lower” primates (lemurs, lorises, and bushbabies) and the Haplorhini or “higher” primates [tarsiers and anthropoids (New and Old World monkeys, greater and lesser apes, and humans)]. Some fossil groups (omomyiforms and adapiforms) can be placed with or near these two extant groupings; however, there is contention whether the Plesiadapiformes represent the earliest relatives of primates and are best placed within the order (as here) or outside it. See also: FOSSIL; MAMMALIA; PHYLOGENY; PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY; PRIMATES. Vast evidence suggests that the order Primates is a monophyletic group, that is, the primates have a common genetic origin. Although several peculiarities of the primate bauplan (body plan) appear to be inherited from an inferred common ancestor, it seems that the order as a whole is characterized by showing a variety of parallel adaptations in different groups to a predominantly arboreal lifestyle, including anatomical and behavioral complexes related to improved grasping and manipulative capacities, a variety of locomotor styles, and enlargement of the higher centers of the brain. Among the extant primates, the lower primates more closely resemble forms that evolved relatively early in the history of the order, whereas the higher primates represent a group that evolved more recently (Fig. 1). A classification of the primates, as accepted here, appears above. Early primates The earliest primates are placed in their own semiorder, Plesiadapiformes (as contrasted with the semiorder Euprimates for all living forms), because they have no direct evolutionary links with, and bear few adaptive resemblances to, any group of living primates. -

Groves #3 Layout 1

Vietnamese Journal of Primatology (2009) 3, 37-44 Diet and feeding behaviour of pygmy lorises (Nycticebus pygmaeus) in Vietnam Ulrike Streicher Wildlife Veterinarinan, Danang, Vietnam. <[email protected]> Key words: Diet, feeding behaviour, pygmy loris Summary Little is known about the diet and feeding behaviour of the pygmy loris. Within the Lorisidae there are faunivorous and frugivorous species represented and this study aimed to characterize where the pygmy loris (Nycticebus pygmaeus) ranges on this scale. Feeding behaviour was observed in adult animals which had been confiscated from the illegal wildlife trade and housed at the Endangered Primate Rescue Center at Cuc Phuong National Park for some time before they were radio collared and released into Cuc Phuong National Park. The lorises were located in daytime by methods of radio tracking and in the evenings they were directly observed with the help of red-light torches. The observed lorises exploited a large variety of different food sources, consuming insects as well as gum and other plant exudates, thus appearing to be truly omnivorous. Seasonal variations in food preferences were observed. Omnivory can be an adaptive strategy, helping to overcome difficulties in times of food shortage. The pygmy loris’ feeding behaviour enables it to rely on other food sources like gum in times when other feeding resource become rare. Gum as an alternative food sources has the advantage of being readily available all year round. However it does not permit the same energetic benefits and consequently the same lifestyle as other food sources. But it is an important part of the pygmy loris’ multifaceted strategy to survive times of hostile environmental conditions. -

Download HEB1330 Primate Diversity.Pdf

HEB 1330: Primate Social Behavior September 15th 2020 Primate Diversity Quiz 1 2 1. What is a spandrel (in an evolutionary context)? (1 point). Provide an example of a spandrel. (1 point) 2. Explain human lactation, using each of Tinbergen’s four questions. (4 points) 3. The table below has information about food distribution and feeding competition for two different groups of Chacma baboons, the Laikipia group and the Drakensberg group. How would you expect female-female relationships to differ between the two groups, and why? (2 points) 3 Overview 1) What is a Primate? 2) Basic Vocabulary 3) Brief Overview of Primate Groups Reading: Boyd R & Silk J. 2015. How Humans Evolved. Chapter 5, pg. 108-125. 4 What is a primate? What am I? 5 Primates are mammals 6 Primates have a Petrosal Bulla 7 Primates have an emphasis on vision rather than smell 8 Primates have a generalized dentition 9 Primates have opposable thumbs and mostly nails instead of claws 10 Primates have increased life spans 11 Primates have slow development 12 Primates have big brains 13 Primates are social 14 Where do primates live? • ~685 species and subspecies of primates • Primates are found in Africa, Asia, South / Central America in tropical regions (mostly forests) 15 Where do non-human primates live? • ~685 species and subspecies of primates • Primates are found in Africa, Asia, South / Central America in tropical regions (mostly forests) 16 Overview 1) What is a Primate? 2) Basic Vocabulary 3) Brief Overview of Primate Groups Reading: Boyd R & Silk J. 2015. How Humans Evolved. -

Effects of Additional Postcranial Data on the Topologies of Early Eocene Primate

Effects of Additional Postcranial Data on the Topologies of Early Eocene Primate Phylogenies Julia Stone ANT 679HB Special Honors in the Department of Anthropology The University of Texas at Austin May 2021 Liza J. Shapiro Department of Anthropology Supervising Professor E. Christopher Kirk Department of Anthropology Second Reader Acknowledgements This project would not have been completed without the help of my thesis supervisor Dr. Liza Shapiro. I was inspired to start the project after taking her courses in Primate Evolution and Primate Anatomy. She also met with me many times throughout this year to discuss the trajectory of the project as well as discuss papers that became the foundation of the thesis. She assisted me through technology issues, unresolved trees, and many drafts, and she provided invaluable guidance throughout this process. I also want to thank Dr. Christopher Kirk for being my second reader and providing extremely helpful insight into how to write about phylogenetic results. He also helped me to be more specific and accurate in all of the sections of the thesis. I learned a lot about writing theses in general due to his comments on my drafts. I also truly appreciate the help of Ben Rodwell, a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin. He provided excellent help and support regarding the Mesquite and TNT software used in this project. ii Effects of Additional Postcranial Data on the Topologies of Early Eocene Primate Phylogenies by Julia Stone, BA The University of Texas at Austin SUPERVISOR: Liza J. Shapiro There are multiple hypotheses regarding the locomotor behaviors of the last common ancestor to primates and which fossil primates best represent that ancestor. -

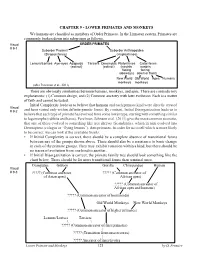

CHAPTER 9 - LOWER PRIMATES and MONKEYS We Humans Are Classified As Members of Order Primates

CHAPTER 9 - LOWER PRIMATES AND MONKEYS We humans are classified as members of Order Primates. In the Linnaean system, Primates are commonly broken down into subgroups as follows. Visual ORDER PRIMATES # 9-1 Suborder Prosimii Suborder Anthropoidea (Strepsirrhines) (Haplorrhines) Lemurs/Lorises Aye-ayes Adapoids Tarsiers Omomyids Platyrrhines Catarrhines (extinct) (extinct) (nostrils nostrils facing facing sideways) down or front) New World Old World Apes Humans monkeys monkeys (after Perelman et al., 2011) There are obviously similarities between humans, monkeys, and apes. There are contradictory explanations: (1) Common design, and (2) Common ancestry with later evolution. Each is a matter of faith and cannot be tested. Initial Complexity leads us to believe that humans and each primate kind were directly created Visual # 9-2 and have varied only within definite genetic limits. By contrast, Initial Disorganization leads us to believe that each type of primate has evolved from some lower type, starting with something similar to lagomorphs (rabbits and hares). Perelman, Johnson et al. (2011) give the most common scenario, that one of these evolved to something like tree shrews (Scandentia), which in turn evolved into Dermoptera (colugos or “flying lemurs”), then primates. In order for us to tell which is more likely to be correct, we can look at the available fossils. • If Initial Complexity is correct, there should be a complete absence of transitional forms between any of the groups shown above. There should also be a resistance to basic change in each of the primate groups. They may exhibit variation within a kind, but there should be no traces of evolution from one kind to another. -

(Tarsius Pumilus) in CENTRAL SULAWESI, INDONESIA

ALTITUDINAL EFFECTS ON THE BEHAVIOR AND MORPHOLOGY OF PYGMY TARSIERS (Tarsius pumilus) IN CENTRAL SULAWESI, INDONESIA A Dissertation by NANDA BESS GROW Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Sharon Gursky-Doyen Committee Members, Michael Alvard Jeffrey Winking Jane Packard Head of Department, Cynthia Werner August 2013 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2013 Nanda Bess Grow ABSTRACT Pygmy tarsiers (Tarsius pumilus) of Central Sulawesi, Indonesia are the only species of tarsier known to live exclusively at high altitudes. This study was the first to locate and observe multiple groups of this elusive primate. This research tested the hypothesis that variation in pygmy tarsier behavior and morphology correlates with measurable ecological differences that occur along an altitudinal gradient. As a response to decreased resources at higher altitudes and the associated effects on foraging competition and energy intake, pygmy tarsiers were predicted to exhibit lower population density, smaller group sizes, larger home ranges, and reduced sexually selected traits compared to lowland tarsiers. Six groups containing a total of 22 individuals were observed. Pygmy tarsiers were only found between 2000 and 2300 m, indicating allopatric separation from lowland tarsiers. As expected, the observed pygmy tarsiers lived at a lower density than lowland tarsier species, in association with decreased resources at higher altitudes. The estimated population density of pygmy tarsiers was 92 individuals per 100 ha, with 25 groups per 100 ha. However, contrary to expectation, home range sizes were not significantly larger than lowland tarsier home ranges, and average NPL was smaller than those of lowland tarsiers. -

A Lynx Natural Brain Endocast from Ingarano (Southern Italy; Late Pleistocene): Taphonomic, Morphometric and Phylogenetic Approaches

Published by Associazione Teriologica Italiana Volume 26 (2): 110–117, 2015 Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy Available online at: http://www.italian-journal-of-mammalogy.it/article/view/11465/pdf doi:10.4404/hystrix-26.2-11465 Research Article A lynx natural brain endocast from Ingarano (Southern Italy; Late Pleistocene): Taphonomic, Morphometric and Phylogenetic approaches Dawid A. Iurinoa,b,∗, Antonio Proficob,c, Marco Cherinb,d, Alessio Venezianob,e, Loïc Costeurb,f, Raffaele Sardellaa,b aDipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Sapienza Università di Roma, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5, 00185, Rome, Italy bPaleoFactory, Sapienza Università di Roma, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5, 00185, Rome, Italy cDipartimento di Biologia Ambientale, Sapienza Università di Roma, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5, 00185 Roma, Italy dDipartimento di Fisica e Geologia, Università degli Studi di Perugia, Via Alessandro Pascoli, 06123 Perugia, Italy eSchool of Natural Sciences and Psychology, John Moores University, James Parsons Building, Byrom Street L3 3AF, Liverpool, United Kingdom fNaturhistorisches Museum Basel, Augustinergasse 2, 4001 Basel, Switzerland Keywords: Abstract Natural brain endocast Carnivora A natural brain endocast from the Late Pleistocene site of Ingarano (Apulia, Southern Italy) has Felidae been investigated in detail using CT scanning, image processing techniques and Geometric Morpho- Lynx metrics to obtain information about the taxonomy and taphonomy of the specimen. Based on its paleontology characteristically felid shape, we compared several measurements of the endocast with those of the geometric morphometrics brains of living Felidae, with a special emphasis on Panthera pardus, Lynx lynx and Felis silvestris phylogenetic signal earlier reported from the same locality. The applied combination of techniques revealed that this specimen is morphometrically closest to the brains of lynxes, and so can be reported as the first Article history: natural endocranial cast of Late Pleistocene Lynx sp.