Chapter 1 Leonardo Sciascia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highway 101 Decision Time: IT’S NOW…OR NEVER!

The BEST things in life are FREE MINEARDS MISCELLANY 19 – 26 April 2012 Vol 18 Issue 16 With GasPods, Bob Evans saves fuel putting the pedal to the metal; Beautiful You’s Megan Simon profiled in The The Voice of the Village SSINCE 1995S New York Times, p. 6 THIS WEEK IN MONTECITO, P. 10 • CALENDAR OF EVENTS, P. 40 • MONTECITO EATERIES, P. 42 Highway 101 Decision Time: IT’S NOW…OR NEVER! Former Montecito Association President J’Amy Brown sounds the alarm over upcoming ten-year highway construction project that could change Montecito forever (story begins on page 21) MUS Carnival Dr. Seuss is the theme again as 43rd annual event – sponsored by Montecito Bank & Trust – takesDr. overSeuss MUS is campusthe theme on Saturday again as April 28, 43rd annual(story event on page – sponsored 12) by Montecito Bank & Trust – takes over MUS campus on Real Estate Four homes priced at just under REAL ESTATE VIEW & $3 million look like Best Buys to 93108 OPEN HOUSE DIRECTORY P.44 Mark Hunt, p. 37 2 MONTECITO JOURNAL • The Voice of the Village • 19 – 26 April 2012 The Premiere Estates of Montecito & Santa Barbara Offered by RANDY SOLAKIAN (805) 565-2208 www.montecitoestates.com License #00622258 Exclusive Representation for Marketing & Acquisition Additional Exceptional Estates Available by Private Consultation 8.4 acres - Ready to Build Montecito - $3,200,000 (additional 28 acres available) 19 – 26 April 2012 MONTECITO JOURNAL 3 INSIDE THIS ISSUE 5 Editorial Bob Hazard urges all to attend Caltrans meeting concerning 101 widening Splish 6 Montecito Miscellany -

Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri's Detective

MAFIA MOTIFS IN ANDREA CAMILLERI’S DETECTIVE MONTALBANO NOVELS: FROM THE CULTURE AND BREAKDOWN OF OMERTÀ TO MAFIA AS A SCAPEGOAT FOR THE FAILURE OF STATE Adriana Nicole Cerami A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures (Italian). Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Dino S. Cervigni Amy Chambless Roberto Dainotto Federico Luisetti Ennio I. Rao © 2015 Adriana Nicole Cerami ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Adriana Nicole Cerami: Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri’s Detective Montalbano Novels: From the Culture and Breakdown of Omertà to Mafia as a Scapegoat for the Failure of State (Under the direction of Ennio I. Rao) Twenty out of twenty-six of Andrea Camilleri’s detective Montalbano novels feature three motifs related to the mafia. First, although the mafia is not necessarily the main subject of the narratives, mafioso behavior and communication are present in all novels through both mafia and non-mafia-affiliated characters and dialogue. Second, within the narratives there is a distinction between the old and the new generations of the mafia, and a preference for the old mafia ways. Last, the mafia is illustrated as the usual suspect in everyday crime, consequentially diverting attention and accountability away from government authorities. Few critics have focused on Camilleri’s representations of the mafia and their literary significance in mafia and detective fiction. The purpose of the present study is to cast light on these three motifs through a close reading and analysis of the detective Montalbano novels, lending a new twist to the genre of detective fiction. -

ORGANIZED CRIME: Sect

ORGANIZED CRIME: Sect. 302 SOCIOLOGY AND HISTORY OF ITALIAN MAFIA SOC 260 Fs January Term 2016 Dr. Sandra Cavallucci NOTE on section: once enrolled, students are required to regularly attend the section of the course that they are enrolled in. Switching sections during the course is not allowed. Credit Hours: 3 Contact Hours: 45 Additional Costs: Approx 20 Euro (details in point #10) Teacher contact: available to see students before and after class: [email protected] 1 - DESCRIPTION One of a long list of Italian words adopted in many other languages, “mafia” is now applied to a variety of criminal organizations around the world. This course examines organized crime in Italy in historical, social and cultural perspective, tracing its growth from the nineteenth century to the present. The chief focus is on the Sicilian mafia as the original and primary form. Similar organizations in other Italian regions, as well as the mafia in the United States, an outgrowth of Sicilian mafia, are also considered. The course analyzes sociological aspects of the mafia including language, message systems, the “code of silence,” the role of violence, structures of power, and social relationships. Also examined are the economics of organized crime and its impact on Italian society and politics. 2 - OBJECTIVES, GOALS and OUTCOMES The objective of this course is to give students an accurate and in-depth understanding of the Italian (Sicilian) mafia. Most foreigners tend to look at the mafia through stereotypes, after forming their impressions of the mafia through popular movies but few go beyond these cinematic images to learn the truth about this criminal phenomenon: the course aims to give the student a completely different picture of the mafia. -

Pubblicazioni N.58

PUBBLICAZIONI Vengono segnalate, in ordine alfabetico per autore (o curatore o parola- chiave), quelle contenenti materiali conservati nell’AP della BCLu e strettamente collegate a Prezzolini, Flaiano, Ceronetti, Chiesa, ecc. Le pubblicazioni seguite dalle sigle dei vari Fondi includono documenti presi dai Fondi stessi. Cinque secoli di aforismi , a cura di Antonio Castronuovo, “Il lettore di provincia”, a. XLVIII, fasc. 149, luglio-dicembre 2017 [ANTONIO CASTRONUOVO , Premessa ; ANDREA PAGANI , La dissimulazione onesta nell’aforisma di Tasso ; GIULIA CANTARUTTI , I clandestini ; SILVIA RUZZENENTI , Tradurre aforismi. Spunti di riflessione e Fragmente di un’autrice tedesca dell’Illuminismo ; MATTEO VERONESI , Leopardi e l’universo della ghnome; NEIL NOVELLO , Una «meta» terrestre a Zürau. Kafka alla prova dell’aforisma ; SANDRO MONTALTO , Aforisti italiani (giustamente?) dimenticati ; GILBERTO MORDENTI , Montherlant: carnets e aforismi ; MASSIMO SANNELLI , Lasciate divertire Joë Bousquet ; ANNA ANTOLISEI , Pitigrilli, un aforista nell’oblio ; SILVANA BARONI , «Ripassa domani realtà!». Pessoa aforista ; ANNA MONACO , Un nemico dell’aforisma: Albert Camus ; SILVIA ALBERTAZZI , Fotorismi: aforismi e fotografia ; MARIA PANETTA , Apologia del lettore indiscreto: Bobi Bazlen e l’aforisma «involontario» ; SIMONA ABIS , Gli aforismi di Gómez Dávila: la dignità come perversione ; FULVIO SENARDI , Francesco Burdin, aforista in servizio permanente ; ANTONIO CASTRONUOVO , L’aforista Maria Luisa Spaziani ; PAOLO ALBANI , L’aforisma tra gesto involontario -

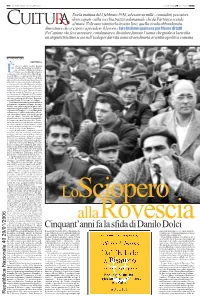

Cinquant'anni Fa La Sfida Di Danilo Dolci

40 LA DOMENICA DI REPUBBLICA DOMENICA 29 GENNAIO 2006 Era la mattina del 2 febbraio 1956, ed erano in mille - contadini, pescatori, disoccupati - sulla vecchia trazzera demaniale che da Partinico scende al mare. Volevano rimetterla in sesto loro, quella strada abbandonata, dimostrare che ci si poteva prendere il lavoro e fare insieme qualcosa per il bene di tutti. Fu l’azione che fece arrestare, condannare e diventare famoso l’uomo che guidava la rivolta: un utopista triestino sceso nell’isola per dar vita a una straordinaria avventura politica e umana ATTILIO BOLZONI PARTINICO ancora senza nome questa strada che dal paese scende fi- no al mare. Ripida nel primo Ètratto, poi va giù dolcemente con le sue curve che sfiorano alberi di pe- sco e di albicocco, passa sotto due ponti, scavalca la ferrovia. L’hanno asfaltata appena una decina di anni fa, prima era un sentiero, una delle tante regie trazze- re borboniche che attraversano la cam- pagna siciliana. È lunga otto chilometri, un giorno forse la chiameranno via dello Sciopero alla Rovescia. Siamo sul ciglio di questa strada di Partinico mezzo se- colo dopo quel 2 febbraio del ‘56, la stia- mo percorrendo sulle tracce di un uomo che sapeva inventare il futuro. Era un ir- regolare Danilo Dolci, uno di confine. Quella mattina erano quasi in mille qui sul sentiero e in mezzo al fango, inverno freddo, era caduta anche la neve sullo spuntone tagliente dello Jato. I pescatori venivano da Trappeto e i contadini dalle valli intorno, c’erano sindacalisti, alleva- tori, tanti disoccupati. E in fondo quegli altri, gli «sbirri» mandati da Palermo, pronti a caricare e a portarseli via quelli lì. -

The Gangster Hero in the Work of Puzo, Coppola, and Rimanelli

Rewriting the Mafioso: The Gangster Hero in the Work of Puzo, Coppola, and Rimanelli Author: Marissa Sangimino Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104214 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2015 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Rewriting the Mafioso: The Gangster Hero in the Work of Puzo, Coppola, and Rimanelli By Marissa M. Sangimino Advisor: Prof. Carlo Rotella English Department Honors Thesis Submitted: April 9, 2015 Boston College 2015 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS!! ! ! I!would!like!to!thank!my!advisor,!Dr.!Carlo!Rotella!for!the!many!hours!(and!many!emails)!that!it! took!to!complete!this!thesis,!as!well!as!his!kind!support!and!brilliant!advice.! ! I!would!also!like!to!thank!the!many!professors!in!the!English!Department!who!have!also! inspired!me!over!the!years!to!continue!reading,!writing,!and!thinking,!especially!Professor!Bonnie! Rudner!and!Dr.!James!Smith.! ! Finally,!as!always,!I!must!thank!my!family!of!Mafiosi:!! Non!siamo!ricchi!di!denaro,!ma!siamo!ricchi!di!sangue.! TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.........................................................................................................................................1-3 CHAPTER ONE: The Hyphenate Individual ..............................................................................................................4-17 The -

An Investigation Into the Rise of the Organized Crime Syndicate in Naples, Italy

THE FIRST RULE OF CAMORRA IS YOU DO NOT TALK ABOUT CAMORRA: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE RISE OF THE ORGANIZED CRIME SYNDICATE IN NAPLES, ITALY by DALTON MARK B.A., The University of Georgia, tbr 2013 Mark 1 In Naples, Italy, an underground society has a hand in every aspect of civilian life. This organization controls the government. This organization has been the police force. This organization has been a judicial board. This organization has maintained order in the jails. This organization is involved in almost every murder, every drug sale, every fixed election. This organization even takes out the garbage. But the first rule of Camorra is you do not talk about Camorra. The success of this crime syndicate, and others like it, is predicated on a principle of omertà – a strict silence that demands non-compliance with authority and non-interference in rival jobs. Presumably birthed out of the desperation of impoverished citizens, the Camorra has grown over the last three centuries to become the most powerful force in southern Italy. The Camorra’s influence in Naples was affirmed when various local governments commissioned the them to work in law enforcement because no other group (including the official police) had the means to maintain order. Since the Camorra took control of the city, they have been impossible to extirpate. This resilience is based on their size, their depravity, their decentralization, and perhaps most importantly, the corruption of the government attempting to supplant them. Nonetheless, in 1911, the Camorra was brought to a mass trial, resulting in the conviction of twenty-seven leaders. -

Elio Gioanola Carlo Bo Charles Singleton Gianfranco Contini

Elio Gioanola Introduzione Carlo Bo Ricordo di Eugenio Montale Charles Singleton Quelli che restano Gianfranco Contini Lettere di Eugenio Montale Vittorio Sereni Il nostro debito verso Montale Vittore Branca Montale crìtico di teatro Andrea Zanzotto La freccia dei diari Luciano Erba Una forma di felicità, non un oggetto di giudizio Piero Bigongiari Montale tra il continuo e il discontinuo Giovanni Macchia La stanza dell'Amiata Ettore Bonora Un grande trìttico al centro della « Bufera » (La primavera hitleriana, Iride, L'orto) Silvio Guarnieri Con Montale a Firenze http://d-nb.info/945512643 Pier Vincenzo Mengaldo La panchina e i morti (su una versione di Montale) Angelo Jacomuzzi Incontro - Per una costante della poesia montaliana Marco Forti Per « Diario del '71 » Giorgio Bàrberi Squarotti Montale o il superamento del soggetto Silvio Ramat Da Arsenio a Gerti Mario Martelli L'autocitazione nel secondo Montale Rosanna Bettarini Un altro lapillo Glauco Cambon Ancora su « Iride », frammento di Apocalisse Mladen Machiedo Una lettera dì Eugenio Montale (e documenti circostanti) Claudio Scarpati Sullo stilnovismo di Montale Gilberto Lonardi L'altra Madre Luciano Rebay Montale, Clizia e l'America Stefano Agosti Tom beau Maria Antonietta Grignani Occasioni diacroniche nella poesia di Montale Claudio Marabini Montale giornalista Gilberto Finzi Un'intervista del 1964 Franco Croce Satura Edoardo Sanguineti Tombeau di Eusebio Giuseppe Savoca L'ombra viva della bufera Oreste Macrì Sulla poetica di Eugenio Montale attraverso gli scritti critici Laura Barile Primi versi di Eugenio Montale Emerico Giachery La poesia di Montale e il senso dell'Europa Giovanni Bonalumi In margine al « Povero Nestoriano smarrito » Lorenzo Greco Tempo e «fuor del tempo» nell'ultimo Montale . -

Antique Traditions of Sicily Tour

Gianluca Butticè P: 312.925.3467 Founder and Owner madrelinguaitaliana.com [email protected] Antique Traditions of Sicily Tour Purpose: Language and Culture Tour Italian Region: Sicily 10 DAYS / 9 NIGHTS SEPTEMBER 14 - 23, 2018 LAND-ONLY PRICE PER PERSON IN DOUBLE ROOM: (min. 10 ppl.) $2,499,00 Tour Leader Gianluca Butticè, Italian Language (L2/LS) Teacher and Founder at Madrelingua Italiana, Inc., will deliver everyday after breakfast a 30 minute language session, aiming to provide an overview of the day ahead and to introduce / familiarize the participants to the main points and key-terms encountered in each activity and / or excursion. Madrelingua Italiana has meticulously designed this Language and Culture Tour of Sicily to show to its participants, antique-traditions & cultural aspects of the most southern and sunny region of Italy, which could never be truly discovered without the commitment of native professionals. 1st day: Palermo Arrival at Palermo Airport, transfer to Hotel. Overnight. 2nd day: Food Market & Palermo & Monreale Tour Breakfast in hotel. Pick up by your private driver and transfer to Capo’s Market. We will start right away exploring the Sicilian culture and cuisin. The itinerary starts with a visit in the Capo Market, the oldest market in Palermo, where we’ll see and taste the famous street food: panelle, arancine, crocchette and pani ca meusa. You will admire the little and colored shacks that characterize the richness of fruits, fishes and meat and the sellers, screaming, to gain your attention. After that you’ll visit Palermo, which extends along the beautiful Tyrrhenian bay. Founded by the Phoenicians on 7th and 8th century BCE, it was conquered by the Arabs in 831 AD, and then started a great period of prosperity. -

Notarbartolo Di Sciara G., Bearzi G

Notarbartolo di Sciara G., Bearzi G. 2005. Research on cetaceans in Italy. In B. Cozzi, ed. Marine mammals of the Mediterranean Sea: natural history, biology, anatomy, pathology, parasitology. Massimo Valdina Editore, Milano (in Italian). RESEARCH ON CETACEANS IN ITALY Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara and Giovanni Bearzi Tethys Research Institute, viale G.B. Gadio 2, 20121 Milano, Italy 1. Introduction Zoology, like other branches of the natural sciences, has expanded greatly from the time of Aristotle, who may be regarded as its founder, to the present day. Zoology started from simple descriptions of animals, based in part on facts and in part on fantasy. Century after century, accounts became increasingly detailed, extending from representations of external features to anatomical descriptions of internal organs, while zoological collections were established to buttress such descriptions with reference material. Increasingly detailed knowledge of the different animal species afforded in the XVIII cent. the adoption of the Linnaean cataloguing system, still valid to this date. Two thousand years of zoological work also set the stage for Darwin’s unifying theory of evolution, which provided an explanation for the mechanisms responsible for the diversity of all existing animal species, of the relationships among species, and between species and their environment. Cetology (cetacean zoology) followed a similar development, although at a slower pace with respect to most branches of zoology. This was because cetaceans have never been easy to study. Compared to most species, and even to most mammals, cetaceans are relatively rare, and the body size of even the smallest species (let alone the largest) made it often problematic to bring specimens to a laboratory or to a collection for detailed investigation. -

Cas Li 306 Venetian Landscapes: a Contemporary Grand Tour

CAS LI 306 VENETIAN LANDSCAPES: A CONTEMPORARY GRAND TOUR Co-taught by Prof. Elisabetta Convento and Prof. Laura Lenci Office Hours: Two hours per week (TBD) or by appointment Office: BU Padua, Via Dimesse 5 – 35122 Padova (Italy) E-mail: Phone: Office (+39) 049 650303 Class Meets: 2 hours, four times a week (Summer), Bu Padua Academic Center Credits: 4 Hub Units: 1+1 (GCI and OSC) Course description There are places that inspire visitors and artists. The morphological aspects of the territory; the colors; the human trace on the physical territory; the history, culture and traditions are but some of the elements of a landscape fascination. The Veneto region, where Padua always played and still plays a lively cultural role, is particularly rich of suggestions and throughout the centuries inspired artists, musicians, writers. Johann W. Goethe, Lord Byron or Henry James wrote beautiful memories of their Italian journey and left us extraordinary depictions of cities like Padua, Venice and Verona surrounded by hills, mountains, lagoon, but also rural landscapes. Following the path of these famous travelers, the course aims to offer students the opportunity to discover the Veneto region through literary and cultural experiences. By means of on-site lessons, readings and field trips, students are able to recognize the local identity that deepens its roots into the landscape (natural and anthropic), culture (progress and tradition), language (Italian and dialect), history and society. During the course, students will read and discuss extracts from works by Luigi Meneghello, Mario Rigoni Stern, Dino Buzzati or Giovanni Comisso to only mention some, and visit places such as the Dolomites, the Veneto countryside, or cities like Padova, Treviso, Vicenza or Venezia. -

Download the Sicilian Pdf Ebook by Mario Puzo

Download The Sicilian pdf ebook by Mario Puzo You're readind a review The Sicilian book. To get able to download The Sicilian you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this ebook on an database site. Book File Details: Original title: The Sicilian Paperback: Publisher: Arrow (2001) Language: English ISBN-10: 9780099580799 ISBN-13: 978-0099580799 ASIN: 0099580799 Product Dimensions:5.1 x 1 x 7.8 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 4284 kB Description: Michael Corleone is returning to the U.S. after the two-year exile to Sicily in which reader left him in The Godfather. But he is ordered to bring with him the young Sicilian bandit, Salvatore Guiliano, who is the unofficial ruler of northwestern Sicily. In his fight to make Sicilians free people, the young folk hero, based on the real-life Giuliano... Review: The Sicilian is a different storyline from The Godfather, but does intersect with Michael Corleone just before and just after his return to the US after that Sollozzo unpleasantness. There also is a surprising connection with Peter Clemenza. If you enjoyed The Godfather, then I believe you will enjoy The Sicilian.... Ebook File Tags: mario puzo pdf, michael corleone pdf, robin hood pdf, salvatore giuliano pdf, corleone family pdf, story line pdf, salvatore guiliano pdf, takes place pdf, good book pdf, better than the godfather pdf, great book pdf, main character pdf, read this book pdf, highly recommended pdf, turi giuliano pdf, sequel to the godfather pdf, puzo is probably best pdf, godfather series pdf, turi guiliano pdf, great story The Sicilian pdf book by Mario Puzo in pdf ebooks The Sicilian the sicilian book sicilian the fb2 sicilian the ebook the sicilian pdf The Sicilian I barely noticed any structural of sicilian issues.