Mid-Twentieth-Century Amencan Evangelicalism's Girl Scouts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Girl Scouts of Kentuckiana Council History 1910S

Girl Scouts of Kentuckiana Council History Girl Scouts has not always been as popular and successful as it is today. In fact, the organization had a somewhat humble beginning. The Movement began on March 12, 1912 with just 18 girls in Savannah, Georgia. Initially founded by Juliette Gordon Low as American Girl Guides, the name of the organization was changed to Girl Scouts in 1913. Her idea was revolutionary, for although times had begun to change, the lives of girls and women were still very limited. They had few opportunities for outdoor recreation, their career options were almost non‐existent, and, as Juliette Low observed, they were expected to be "prim and subservient." But convention did not impede Juliette Low. Her vision of Girl Scouting became a reality that actively challenged the norms that defined the lives of girls. She constantly encouraged girls to learn new skills and emphasized citizenship, patriotism, and serving one’s country. Girl Scouts of Kentuckiana History & Archive Committee invites anyone interested in preserving Girl Scout history, developing Girl Scout history related programs and events, creating historic exhibits, and/or interviewing and collecting oral Girl Scout histories to contact the history and archive committee at [email protected] for more information. 1910s In Louisville, the first unofficial Girl Scout troop was organized in July of 1911 by Charlotte Went Butler, an outdoors‐loving 11‐year‐old, even before the Girl Scouts was officially founded in Georgia. A patrol of eight girls was formed as members of Boy Scout troop #17. The girls met in the basement of the Highland Library. -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 68 NUMBER i Archeological Investigations in New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah (With 14 Plates) BY J. WALTER FEWKES (Publication 2442) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION MAY, 1917 Zh £orb (§aitimovt (ptees BALTIMOltlC, MI)., U. S. A. ARCHEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN NEW MEXICO, COLORADO, AND UTAH By J. WALTER FEWKES (With 14 Plate's) INTRODUCTION During- the year 1916 the author spent five months in archeological investigations in New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah, three of these months being given to intensive work on the Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado. An account of the result of the Mesa Verde work will appear in the Smithsonian Annual Report for 191 6, under the title " A Prehistoric Mesa Verde Pueblo and Its People." What was accomplished in June and October, 1916, before and after the work at the Mesa Verde, is here recorded. As archeological work in the Southwest progresses, it becomes more and more evident that we can not solve the many problems it presents until we know more about the general distribution of ruins, and the characteristic forms peculiar to different geographical locali- ties. Most of the results thus far accomplished are admirable, though Hmited to a few regions, while many extensive areas have as yet not been explored by the archeologist and the types of architecture peculiar to these unexplored areas remain unknown. Here we need a reconnoissance followed by intensive work to supplement what has already been done. The following pages contain an account of what might be called archeological scouting in New Mexico and Utah. -

Frederic C. Pachman

New Jersey Scout Museum Newsletter Volume 7, Number 1 Summer 2011 President’s Message careers of the two premier artists who combined, have held the title of “Official At the New Jersey Scout Museum, we Artist to the Boy Scouts of America” for the are always working to justify our mission past nine decades. statement: The NJSM members and friends who OUR MISSION attended this event were treated to a photographic program and lecture that will To preserve artifacts relating to the history long be remembered. Our thanks and of Both Boy and Girl Scouting in New Jersey appreciation to Joe and Jeff Csatari for their and to educate the public about Scouting’s friendship and fellowship. role in our communities and nation in developing young people into responsible citizens. and leaders. Frederic C. Pachman President, New Jersey Scout Museum On October 3, the New Jersey Scout Museum was privileged to host a program featuring Joseph and Jeff Csatari, as they discussed their new book Norman Rockwell’s Boy Scouts of America (Dorling Kindersley, 2009). This title is a must for every Scout library. A signal feature of the Boy Scouts of America has been the artwork that has inspired and documented the members, history, and traditions of our organization. Lee Marconi, Jeff Csatari, Joseph Csatari, Fred Pachman From the earliest days of the BSA, whether in line drawings or color lithographs, artists have drawn and painted images that have adorned the cover of the Boy Scout Handbook, appeared in pages of Boy’s Life, and illustrated the activities of Scouts and Scouters. -

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’S Historical Membership Patterns

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns BY Matthew Finn Hubbard Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert ____________________________ Dr. Terry Slocum ____________________________ Dr. Xingong Li Date Defended: 11/22/2016 The Thesis committee for Matthew Finn Hubbard Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert Date approved: (12/07/2016) ii Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to examine the historical membership patterns of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) on a regional and council scale. Using Annual Report data, maps were created to show membership patterns within the BSA’s 12 regions, and over 300 councils when available. The examination of maps reveals the membership impacts of internal and external policy changes upon the Boy Scouts of America. The maps also show how American cultural shifts have impacted the BSA. After reviewing this thesis, the reader should have a greater understanding of the creation, growth, dispersion, and eventual decline in membership of the Boy Scouts of America. Due to the popularity of the organization, and its long history, the reader may also glean some information about American culture in the 20th century as viewed through the lens of the BSA’s rise and fall in popularity. iii Table of Contents Author’s Preface ................................................................................................................pg. -

Stem Merit Badge Fair!

March 1, 2020 Great Southwest Council, Boy Scouts of America | Council Website Eagle Scout Application Verification Reminder Once the Scout has completed all requirements and the Unit Approval for the Eagle rank, the following items must be submitted to the Council office for verification: Eagle Scout rank application, completed project workbook and signed letter of ambition/life purpose. Please allow three days for staff to review Eagle items for accuracy and completion. Once staff has reviewed the Eagle items, whoever turned in the Eagle items will be notified. At that time, the Eagle Board of Review can be scheduled with the District Advancement Chair. Great Southwest Council Earns Recognition as New Mexico Family Friendly Workplace Our Council earned distinction for its workplace policies by Family Friendly New Mexico, a statewide project developed to recognize companies that have adopted policies that give New Mexico businesses an edge in recruiting and retaining the best employees. In This Issue STEM Day Globetrotters Commissioner College Taos Ski Valley Merit Badge Adventure Camp Cub Scout Summer Camps New Gorham Ranger Wilderness First Aid Training Gorham Scout Ranch STEM MERIT BADGE FAIR! Gorham Cub Camps SATURDAY, MARCH 14, 2020 Partnership Update FOS UNM CENTENNIAL ENGINEERING CENTER NESA 300 REDONDO DRIVE ALBUQUERQUE 2021 Jamboree 8:30 AM - 4:30 PM Governors Ball Printing Documents COST $10.00 INCLUDES LUNCH Internet Advancement Seven Layers of YPT Amazon Smile MERIT BADGE SELECTIONS: Support Our Sponsors AMERICAN BUSINESS -

K. Ian Shin Curriculum Vitae (Updated July 2020)

K. IAN SHIN CURRICULUM VITAE (UPDATED JULY 2020) 2640 Haven Hall 435 S. State Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1003 [email protected] ACADEMIC POSITIONS University of Michigan Assistant Professor of History and American Culture 2018–Present Core Faculty, Asian/Pacific Islander American Studies Program Faculty Associate, Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies Bates College Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow and Lecturer in History 2016–2018 EDUCATION Columbia University in the City of New York Ph.D., History 2016 M.Phil., History 2013 M.A., History 2012 Amherst College A.B., magna cum laude 2006 PUBLICATIONS Book manuscript Imperfect Knowledge: Chinese Art and American Power in the Transpacific Progressive Era (in progress) Peer-reviewed journal articles “A Chinese Art ‘Arms Race’?: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism in Chinese Art Collecting and Scholarship Between the United States and Europe, 1900–1920,” Journal of American- East Asian Relations 23 (2016): 229–256. “Art for the ‘Hardware City’: The New Britain Museum of American Art and Cultural Life in a Small New England City, 1903–1964,” Connecticut History Review 54.1 (spring 2015): 51– 75. Book chapters “‘The farthest West shakes hands with the remotest East’: Amherst College, China, and Collegiate Cosmopolitanism in the Nineteenth Century,” in Amherst in the World: A Bicentennial Essay Collection, ed. Martha Saxton (Amherst: Amherst College Press, 2020), 183–200 Book reviews Review of Sticky Rice: A Politics of Intraracial Desire, by Cynthia Wu, Journal of Asian American Studies 23, no. -

Nelson County Resources

Directory A 19th Hole Golf Club, Joe Dodson, Pres. Contact: Bill Sheckles 502-348-3929 502-348-2346 AA 502-349-1671 502-252-5772 AARP, Jane Durbin 502-348-5589 Active Day of Bardstown 502-350-0663 Adecco 502-349-1922 Adult Crisis Stabilization Unit (Elizabethtown, Ky.) 270-737-1360 Advocacy & Support Center 270-234-9236 Advocates for Autism Awareness 502-348-2842 or 502-349-0214 Affordable Hearing Aids 502-331-0017 Al-Anon 502-348-1515 502-348-5795 502-348-2824 502-348-9464 Al-Ateen 502-252-8135 or 502-348-5250 American Arthritis Foundation National: 800-383-6843 Regional: 513-271-4545 Local: 502-348-3369 American Cancer Society, Paige Vollmer 1-800-227-2345 and 502-560-6001 Sister Eva - Road to Recovery 502-348-5434 Penny Smith - Relay for Life 502-507-0006 Lou Smith 502-827-1400 (Also see Kentucky Cancer Program listing) American Heart Association, Kathy Renbarger 1-800-242-8721 and 502-587-8641 American Legion Post 121, Charles Wimsatt (348-2208) 502-969-9675 Sam Smith 502-507-4727 American Legion Post 121 Auxiliary, Michelle Elmore 502-549-3631 American Legion Post 167, (Abraham Lincoln Post) Sidney C. Shouse 502-348-9209 American Legion Post 167 Auxiliary, Georgia Girton 502-348-9420 American Legion Post 288, Bloomfield 502-252-9903 Tom Higdon 502-348-2698 American Legion Post 288 Auxiliary, Barbara Bivens 502-275-9811 American Lung Association Contact: Jennifer Hollifield Ext. 18 800-586-4872 Contact: Susie Lile Ext. 10 502-363-2652 Helpline: 800-548-8252 American Red Cross, Mary Sue Brown 502-348-1893 Doug Alexander 502-827-1505 -

Nixon Peabody Diversity Update

Nixon Peabody Diversity Update July 2007 Plan now to attend: Inside this issue: Nixon Peabody’s first firmwide Diversity is gaining importance with clients 3 forum for diverse attorneys Nixon Peabody’s GLBT Affinity Group meets in Boston 4 Be sure to mark your calendars now for Thursday and Friday, November 1 GLBT sponsorship roundup 6 and November 2, when Nixon Peabody will hold its first firmwide path- Firm helps sponsor ways to success forum for minority and GLBT attorneys. Mediation Advocacy Training 7 Nixon Peabody attends NALP “Creating a Strategic Plan for Diversity in Business Development” will be Diversity Summit 7 held at the Tarrytown House Estate and Conference Center, Tarrytown, Nixon Peabody cosponsors New York. The program has not been finalized, as speakers and the agenda diversity reception 9 are currently under development. However, for planning purposes, please John Higgins selected for award, appointed to leadership roles 10 assume that the conference will begin on Thursday afternoon and contin- Nixon Peabody helps judge ue through Friday afternoon. Details regarding accommodations and trav- McKnight Moot Court Competition 10 el arrangements are also pending. Information about these specifics will be Firm helps support Asian American provided as the date draws nearer. Law Fund 11 International Franchise Association Exposure 12 Nixon Peabody sponsors LexNoir Minority Corporate Counsel Corporate Counsel Forums 12 Laurie Miller named Most recognizes Nixon Peabody Influential Woman Lawyer 13 Nixon Peabody was selected by the Minority Corporate Counsel Laurie Miller selected for prestigious posts 14 Association (MCCA) to receive the Thomas L. Sager Award for the Mid- President of the National Association Atlantic Region in recognition of Nixon Peabody’s sustained commitment of Women Lawyers joins firm 14 to diversity and minority issues, especially regarding hiring, retention, and continued on the next page . -

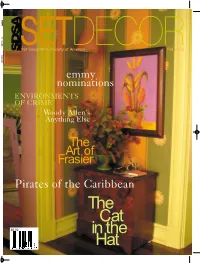

The Cat in The

Cover 9/15/03 2:00 PM Page 1 SET DECOR Set Decorators Society of America Fall 2003 Fall 2003 emmy nominations ENVIRONMENTS OF CRIME Woody Allen’s Anything Else The Art of Frasier Pirates of the Caribbean The Cat $5.00 in the Hat Cover 9/11/03 8:11 AM Page 2 Serving The Film Industry For Over Sixty Years The Ultimate Destination For Antiques 6850-C Vineland Ave., North Hollywood, CA 91605 NEWEL ART GALLERIES, INC. (818)980-4371 • www.floraset.com 425 EAST 53RD STREET NEW YORK, NY 10022 TEL: 212-758-1970 FAX: 212-371-0166 WWW.NEWEL.COM [email protected] SDSA FALL 2003 9/7 9/10/03 9:45 AM Page 3 UNIVERSAL STUDIOS PProperty/GRAPHICroperty/GRAPHIC DESIGNDESIGN && SignSign Shop/HardwareShop/Hardware For All Of Your Production Needs Our goal is to bring your show in on time and on budget PROPERTY/DRAPERY • Phone 818.777.2784; FAX 818.866.1543 • Hours 6 am to 5 pm GRAPHIC DESIGN & SIGN SHOP • Phone 818.777.2350; FAX 818.866.0209 • Hours 6 am to 5 pm HARDWARE • Phone 818.777.2075; FAX 818.866.1448 • Hours 6 am to 2:30 pm SPECIAL EFFECTS EQUIPMENT RENTAL • Phone 818.777.2075; Pager 818.215.4316 • Hours 6 am to 5 pm STOCK UNITS • Phone 818.777.2481; FAX 818.866.1363 • Hours 6 am to 2:30 pm UNIVERSAL OPERATIONS GROUP 100 UNIVERSAL CITY PLAZA • UNIVERSAL CITY, CA 91608 • 800.892.1979 T HE FILMMAKERS DESTINATION WWW.UNIVERSALSTUDIOS.COM/ STUDIO SDSA FALL 2003 9/7 9/10/03 9:45 AM Page 4 SDSA FALL 2003 9/7 9/10/03 9:45 AM Page 5 On behalf of BACARDI® U.S.A., Inc. -

Our M Ission

JUNE 2014 VOLUME 37, NUMBER 3 PAID NM Permit 8 ® CIMARRON T HE M AGAZINE OF T HE P HILMON T S TAFF A ss OCIAT ION® U.S. POSTAGE Non-Profit Organization HIGH COUNTRY check us out! www.philstaff.com ® Mission unites (PSA) Association Staff Philmont The and present— staff—past Philmont the adventure, purpose of serving the the for Ranch Scout Philmont of experience and heritage Boy Scouts of America. and the 17 DEER RUN ROAD CIMARRON NM 87714 Our Mission HIGH COUNTRY®—VOLUME 37, NUMBER 3 PHILMONT STAFF ASSOCIATION® JUNE 2014 BOARD OF DIRECTORS ED PEASE, EDITOR MARK DIERKER, LAYOUT EDITOR JOHN MURPHY, PRESIDENT COLLEEN NUTTER, VICE PRESIDENT, MEMBERSHIP RANDY SAUNDERS, AssOCIATE EDITOR TIM ROSSEISEN, VICE PRESIDENT, SERVICE BILL CAss, COPY EDITOR WARREN SMITH, VICE PRESIDENT, DEVELOPMENT DAVE KENNEKE, STAFF CONTRIBUTOR ADAM FROMM, SECRETARY KEVIN “LEVI” THOMAS, CARTOONIst MATT LINDSEY, TREASURER in this issue CONTRIBUTING EDITORS NATIONAL DIRECTORS columns ROBERT BIRKBY DAVID CAFFEY AMY BOYLE BILL CAss GREGORY HOBBS KEN DAVIS WARREN SMITH MARK STINNEtt BRYAN DELANEY 4 from the prez MARY STUEVER STEPHEN ZIMMER CATHERINE HUBBARD LEE HUCKSTEP 16 short stuff - the dance HIGH COUNTRY® IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE STEVE RICK 28 ranch roundup - eric martinez PHILMONT STAFF AssOCIATION® AND IS PUBLISHED SIX TIMES PER YEAR AS A BENEFIT TO Its MEMBERS. REGIONAL DIRECTORS NORTHEAST © 2014, THE PHILMONT STAFF AssOCIATION, INC. KATHLEEN SEITZ articles ALL RIGHts RESERVED. NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED FOR RICK TOUCHETTE PREVIOUSLY COPYRIGHTED OR PUBLIC MATERIAL. PERMIssION GRANTED FOR NON-COMMERCIAL REPRINTING CENTRAL 5 mysery solved OR REDIstRIBUTION WITH PROPER AttRIBUTION. MITCH STANDARD 6 psa news - bill mckown PHIL WINEGARDNER HIGH COUNTRY®, PHILMONT STAFF AssOCIATION®, 8 psa news - amigos needed PSA® AND THE OFFICIAL PSA LOGO® SOUTHERN ARE ALL REGIstERED TRADEMARks OF: ANNE MARIE PINKENBURG 10 psa news - rayado/rocs DOUG WAHL THE PHILMONT STAFF AssOCIATION, INC. -

Eleanor P. Eells Award

Eleanor P. Eells Award 1976 Blue Star Camping Unlimited (NC) Datsun-National YMCA Campership Program The Echo Lake Idea (NY) Environmental Studies Program/College Settlement Camps (PA) Family Weekend Program, Camp Easter-in-the-Pines (NC) Intergrouping Program, Camp Henry Horner (IL) The Metropolitan Camp Council (MI) Trail Blazer Camps (NJ) 1977 Competency Based Pre-Camp Program, Girl Scouts of Genessee Valley (NY) The High-Rise Program of the Institute of Human Understanding (VT) 4-H Juvenile Justice Program, The Utah State University Extension Service Summer Day Camp Program of the St. Louis Assn for Retarded Children Walkabout Program; Nine Combined Northern California Girl Scout Councils 1978 Camp Running Brave, South Carolina Chapter of National Hemophilia Foundation Roving Day Camp-Shawnee Council of Camp Fire, Dayton, Ohio Salesmanship Club of Dallas and Campbell Loughmiller, Retired Director “To Light a Spark” – 16mmfilm, Grove a Gates 1979 Associated Marine Institutes, Inc. (FL) Circle M Day Camp (IL) Senior Adult Camp, University of Oregon Village Summer Swimming Program, Chugach Council of Camp Fire (Alaska) 1980 Albany Park Community Center Day Camp (IL) Building Wellness Lifestyles in a Camp Setting; Frost Valley YMCA (NJ) Camp Lions Adventure Wilderness School (CLAWS); Touch of Nature Environment Center, Southern Illinois University (IL) Kiwanis, Camp Wyman (MO) Project D.A.R.E., Ministry of Community and Social Services (Ontario, Canada) 1981 The Greater Kansas City Camping Collaboration (MO) The Homestead Program of Bar -

United States Bankruptcy Court

EXHIBIT A Exhibit A Service List Served as set forth below Description NameAddress Email Method of Service Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 168 Read Ave Tuckahoe, NY 10707-2316 First Class Mail Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 19 Hillcrest Rd Bronxville, NY 10708-4518 First Class Mail Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 39 7Th St New Rochelle, NY 10801-5813 First Class Mail Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 58 Bradford Blvd Yonkers, NY 10710-3638 First Class Mail Adversary Parties A Group Of Citizens Westchester Putnam 388 Po Box 630 Bronxville, NY 10708-0630 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Abraham Lincoln Council Abraham Lincoln Council 144 5231 S 6Th Street Rd Springfield, IL 62703-5143 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Abraham Lincoln Council C/O Dan O'Brien 5231 S 6Th Street Rd Springfield, IL 62703-5143 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Alabama-Florida Cncl 3 6801 W Main St Dothan, AL 36305-6937 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Alameda Cncl 22 1714 Everett St Alameda, CA 94501-1529 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Alamo Area Cncl#583 2226 Nw Military Hwy San Antonio, TX 78213-1833 First Class Mail Adversary Parties All Saints School - St Stephen'S Church Three Rivers Council 578 Po Box 7188 Beaumont, TX 77726-7188 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Allegheny Highlands Cncl 382 50 Hough Hill Rd Falconer, NY 14733-9766 First Class Mail Adversary Parties Aloha Council C/O Matt Hill 421 Puiwa Rd Honolulu, HI 96817 First