We Have Met the Alien

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAKEDNESS on MARS by Woodrow Edgar Nichols, Jr

NAKEDNESS ON MARS by Woodrow Edgar Nichols, Jr. INTRODUCTION When Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote A Princess of Mars and its sequels, he was writing the legal pornograpy of the day. He wrote what was the literary equivalent of a peep show, which we know he was fond of from his 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition midway adventures. (See, ERBzine #1275, chpt. 6.) This is where Little Egypt became an international celebrity. Because no acts of sex are explicitly described in this series, this fact passes mainly unnoticed to the modern reader, but a discerning eye sees on almost every page naked people with their sexual organs fully exposed, female breasts enhanced in leather harnesses, near rape scenes, acts of perverse cruelty and sado-masochistic bondage, including descriptions of violence, beheadings, and dismemberings, that put Kill Bill: Part One to shame. This would have been shocking literature in its day. It was still shocking when C.S. Lewis followed suit in 1944 by having the inhabitants of Perelandra appear as naked as Adam and Eve, without fig leaves. I can only imagine the kind of moral outrage it must have induced in the minds of Puritanical prudes and Victorian moralists, so influential in politics and the arts at the time. I don’t have to imagine too hard. My mother, a typical Victorian prude who hated Hugh Hefner till the day she died, knew all about ERB. When I was in the fifth grade, around ten years old in 1957, I visited with a friend after school one day. My friend’s mother had been an artist for Disney in the days of Fantasia and was the opposite of my mother. -

A Barso O M Glo Ssary

A BARSO O M GLO SSARY DAV ID BRUC E BO ZARTH HTML Version Copyright 1996-2001 Revisions 2003-5 Most Current Edition is online at http://www.erblist.com PD F Version Copyright 2006 C O PYRIGH TS and O TH ER IN FO The m ost current version of A Barsoom G lossary by D avid Bruce Bozarth is available from http://www.erblist.com in the G lossaries Section. SH ARIN G O R DISTRIBUTIN G TH IS FILE This file m ay be shared as long as no alterations are m ade to the text or im ages. A Barsoom G lossary PD F version m ay be distributed from web sites AS LO N G AS N O FEES, CO ST, IN CO ME, O R PRO FIT is m ade from that distribution. A Barsoom G lossary is N O T PU BLIC D O MAIN , but is distributed as FREE- WARE. If you paid to obtain this book, please let the author know w here and how it w as obtained and w hat fee w as charged. The filenam e is Bozarth-ABarsoom Glossary-illus.pdf D o not change or alter the filenam e. D o not change or alter the pdf file. RO LE PLAYERS and GAM E C REATO RS O ver the years I have been contacted by RPG creators for perm ission to use A BARSO O M G LO SSARY for their gam es as long as the inform ation is N O T printed in book form , nor any fees, cost, incom e, or profit is m ade from m y intellectual property. -

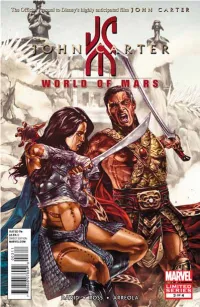

John Carter World of Mars #3

PART THREE OF FOUR BASED ON CHARACTERS CREATED BY EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS AND THE SCREENPLAY JOHN CARTER BY ANDREW STANTON & MARK ANDREWS AND MICHAEL CHABON PETER DAVID LUKE ROSS ULISES ARREOLA WRITER ARTIST COLOR ARTIST MICO SUAYAN & MORRY HOLLOWELL VC’S CORY PETIT COVER ARTISTS LETTERER RACHEL PINNELAS SANA AMANAT & JON MOISAN MAYELA GUTIERREZ EDITOR PRODUCTION ASSISTANT EDITORS AXEL ALONSO JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY EDITOR IN CHIEF CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER PUBLISHER SPECIAL THANKS TO LAURA SANDOVAL, LESLIE STERN, MATTHEW FRANK, KEVIN KURTZ AND RALPH MACCHIO To find MARVEL COMICS at a local comic and hobby shop, go to www.comicshoplocator.com or call 1-888-COMICBOOK. JCOMWORLD2011003_int.indd 1 11/11/11 5:11 PM My princess, the incomparable Dejah Thoris, plunged toward what she thought would be certain doom… …only to feel powerful gusts emerging from below her… …cushioning her fall even as they blew the sand around her back to the surface. A fluke of the wind, lowering me to safety? Or is there something more sinister at work? Either way, one thing remains consistent… JCOMWORLD2011003_int.indd 2 11/11/11 5:11 PM You remain my prisoner. I walk, not More than at your command, that… but because I had already resolved You to head in this are my direction. prize. Start walking. Salve your wounded ego however you wish. How do you Do you harbor some envision this demented notion playing out, that, if I spend Sab Than? sufficient time with you, I will develop feelings for you? Your feelings are of little relevance, Dejah Thoris. -

A PRINCESS of MARS by Edgar Rice Burroughs

A PRINCESS OF MARS by Edgar Rice Burroughs CHAPTER I ON THE ARIZONA HILLS I am a very old man; how old I do not know. Possibly I am a hundred, possibly more; but I cannot tell because I have never aged as other men, nor do I remember any childhood. So far as I can recollect I have always been a man, a man of about thirty. I appear today as I did forty years and more ago, and yet I feel that I cannot go on living forever; that some day I shall die the real death from which there is no resurrection. I do not know why I should fear death, I who have died twice and am still alive; but yet I have the same horror of it as you who have never died, and it is because of this terror of death, I believe, that I am so convinced of my mortality. And because of this conviction I have determined to write down the story of the interesting periods of my life and of my death. I cannot explain the phenomena;I can only set down here in the words of an ordinary soldier of fortune a chronicle of the strange events that befell me during the ten years that my dead body lay undiscovered in an Arizona cave. I have never told this story, nor shall mortal man see this manuscript until after I have passed over for eternity. I know that the average human mind will not believe what it cannot grasp, and so I do not purpose being pilloried by the public, the pulpit, and the press, and held up as a colossal liar when I am but telling the simple truths which some day science will substantiate. -

JOHN CARTER Production Notes

JOHN CARTER (2012) PRODUCTION NOTES JOHN CARTER Production Notes Release Date: March 9, 2012 (3D/2D) Studio: Walt Disney Pictures Director: Andrew Stanton Screenwriter: Andrew Stanton, Mark Andrews, Michael Chabon Starring: Taylor Kitsch, Lynn Collins, Samantha Morton, Mark Strong, Ciaran Hinds, Dominic West, James Purefoy, Daryl Sabara, Polly Walker, Bryan Cranston, Thomas Hayden Church, Willem Dafoe Genre: Action, Adventure, Sci-Fi MPAA Rating: PG-13 (for intense sequences of violence and action) Official Website: Disney.com/JohnCarter From Academy Award®–winning filmmaker Andrew Stanton comes "John Carter"—a sweeping action- adventure set on the mysterious and exotic planet of Barsoom (Mars). "John Carter" is based on a classic novel by Edgar Rice Burroughs, whose highly imaginative adventures served as inspiration for many filmmakers, both past and present. The film tells the story of war-weary, former military captain John Carter (Taylor Kitsch), who is inexplicably transported to Mars where he becomes reluctantly embroiled in a conflict of epic proportions amongst the inhabitants of the planet, including Tars Tarkas (Willem Dafoe) and the captivating Princess Dejah Thoris (Lynn Collins). In a world on the brink of collapse, Carter rediscovers his humanity when he realizes that the survival of Barsoom and its people rests in his hands. © 2012 Walt Disney Pictures 1 JOHN CARTER (2012) PRODUCTION NOTES SYNOPSIS Walt Disney Pictures presents the epic, action-adventure film "John Carter," based on the Edgar Rice Burroughs classic, "A Princess of Mars," the first novel in Burroughs Barsoom series. 2012 marks the 100th anniversary of Burroughs' character John Carter, the original space hero featured in the series, who has thrilled generations with his adventures on Mars. -

A Princess of Mars

Sample file Sample file Sample file Sample file Line Development Literary Consultant Cartography Marketing Executive JACK NORRIS SCOTT TRACY GRIFFIN FRANCESCA BAERALD PANAYIOTIS LINES BENN GRAYBEATON Art Direction Publishing Director Scheduling SAM WEBB KATYA THOMAS CHRIS BIRCH STEVE DALDRY VIRGINIA PAGE SAM WEBB Operations Director Publishing Assistant Rules Development Cover Art RITA BIRCH VIRGINIA PAGE BENN GRAYBEATON BJÖRN BARENDS Head of Development Assistant Sales Manager JACK NORRIS Internal Art ROB HARRIS COLE LEADON VIRGINIA PAGE MICHELE GIORGI DEVELOPED FROM THE ORIGINAL 2D20 CHAIM GARCIA Head of RPG Community Support SYSTEM DESIGN BY JAY LITTLE, FOR PAOLO PUGGIONI Development LLOYD GYAN MUTANT CHRONICLES CRISTI PICU SAM WEBB SHAUN HOCKINGS BJÖRN BARENDS Writing Business Manager Social Media TOMA FEIZO GAS Management JACK NORRIS RODRIGO GONZALES CAMERON DICKS SALWA AZAR JASON BRICK MARTIN SOBR Production Manager With Thanks to Editing and Proofing Logo Design STEVE DALDRY JAMES SULLOS MICHAL E CROSS PETER GROCHULSKI KEITH GARRETT CATHY WILBANKS TIM GRAY Graphic Design Sales Manager TYLER WILBANKS VIRGINIA PAGE CHRIS WEBB RHYS KNIGHT CHRISTOPHER PAUL CAREY Modiphius Entertainment Ltd, 2nd Floor, The 2d20 system and Modiphius Logos are copyright Modiphius Entertainment Ltd 2019. All 2d20 system text is copyright Modiphius Entertainment Ltd. Any 39 Harwood Road, London, SW6 4QP, England unauthorised use of copyrighted material is illegal. Any trademarked names are used in a fictional manner; no infringement is intended. This is a work of fiction. Produced by: Standartų Spaustuvė, UAB, 39 Any similarity with actual people and events, past or present, is purely coincidental and unintentional except for those people and events described in an historical Dariaus ir Girėno, Str., LT-02189 Vilnius, Lithuania context. -

The Portrayal of Patriarchal Oppression Towards Dejah Thoris in the John Carter Movie by Andrew Stanton

e-ISSN 2549-7715 | Volume 5 | Nomor 2 | April 2021 | Hal: 334—348 Terakreditasi Sinta 4 THE PORTRAYAL OF PATRIARCHAL OPPRESSION TOWARDS DEJAH THORIS IN THE JOHN CARTER MOVIE BY ANDREW STANTON Rudiansyah, Satyawati Surya, Fatimah M. English Department, Faculty of Cultural Sciences Mulawarman University Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Gender inequality between men and women are still having the same core problematic in the real life. This research is aimed to answer the questions about the portrayal of the patriarchal system in the John Carter movie and the influence of patriarchal system towards Dejah Thoris’ life in that movie. This research used two theories, namely Johnson’s Patriarchal theory and Young’s Oppression theory. The method that had been used by the researcher was the qualitative method. The result of this research shows that there are four kinds of patriarchal system. First, men dominate in politic sphere, military and domestic field. Second, men are identified as the leaders who have the ability to control and dominate women. Third, men regularly are involved in any situation and they always become the center of attention in society. Lastly, men character in the movie shows their obsession with control, it proved by their passion to controlling over in wide scale both in private and public sphere. Then, the fact about how Dejah Thoris is the victim of the oppressor that makes her life exploited, marginalized, less of power, forced by cultural imperialism, and treated violently. Despite, she resists to be silent and accept her path as an inferior person, however, she still be taken out and neglected. -

The Tarzan / John Carter / Pellucidar / Caspak / Moon / Carson of Venus Chronology

The Tarzan / John Carter / Pellucidar / Caspak / Moon / Carson of Venus Chronology Compiled by Win Scott Eckert Based on: • Philip José Farmer's Tarzan Chronology in Tarzan Alive • John Flint Roy’s A Guide to Barsoom • Further research by Win Scott Eckert This Chronology covers the shared worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ fantastic creations: Tarzan, John Carter of Mars, the Inner World of Pellucidar, Caspak, the Moon, and Carson of Venus. It is my contention that the Tarzan, Pellucidar, and Caspak stories take place in the same universe, a dimension that we will call The Wold Newton Universe (WNU). John Carter and Carson Napier also were born in and start out in the WNU, but their adventures carry them to an alternate dimension, which we shall call the Edgar Rice Burroughs Alternate Universe (ERB-AU). The stories listed on The Wold Newton Universe Crossover Chronology establish that John Carter's Barsoom (from which two invasions, the first Martian invasion against Earth and the second Martian invasion against Annwn, were launched - see Mars: The Home Front) exists in the same alternate universe that contains Carson Napier's Amtor (Venus). It is probable that Zillikian (the planet on the opposite side of the Sun from Earth in Bunduki) is also contained in this alternate universe, the ERB-AU, as well as Thanator (as shown in the Jandar of Callisto series). Humanity's name for their planet in the ERB-AU is Annwn, not Earth (see The Second War of the Worlds), and is called Jasoom by natives of Barsoom. The alternate future described in Burroughs' The Moon Maid and The Moon Men, then, must be the future in store for the planet Annwn. -

Warriors of Mars

ADDITIONAL Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns Playable with Paper and Pencil And Miniature Figures SUPPLEMENT WARRIORS OF MARS BY “DOC” NOT Published by TSR RULES Price $0.00 Supplement WARRIORS OF MARS BY “DOC” With Special Thanks and in tribute to E. Gary Gygax, Dave Arneson, and Edgar Rice Burroughs Based upon the original Warriors of Mars rules for miniature warfare by Gary Gygax and Brian Blume Illustrations by Dave Sutherland, Tracy Lesch & Gary Kwapisz Proofing and Layout: The Grey Elf Additional Monster Stats (Darseen, Malagor, Orluk, Thoat/Zitidar): The Grey Elf Additional Monster Text (Darseen, Malagor, Orluk, Thoat/Zitidar): Falconer Cover by Frank Frazetta 2 CONTENTS PART ONE: MEN AND MAGIC ....................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 5 CHARACTERS ............................................................................................... 6 FIGHTING MAN ........................................................................................ 6 BERSEKER ................................................................................................. 6 SCOUT ........................................................................................................ 6 ASSASSIN ................................................................................................... 8 PSION ......................................................................................................... -

A Princess of Mars

A PRINCESS OF MARS Edgar Rice Burroughs The preparer of this public-domain (U.S.) text is unknown. The Project Gutenberg edi- tion (designated “pmars11”) was converted to LATEX using GutenMark software and re-edited by Ron Burkey. Some correc- tions from “pmars13.txt” (credited to Andrew Sly) were also applied. Report problems to [email protected]. Revision B1 differs from B in that “—-” has everywhere been replaced by “—”. Revision: B1 Date: 01/27/2008 Contents CHAPTER I. ON THE ARIZONA HILLS 1 CHAPTER II. THE ESCAPE OF THE DEAD 11 CHAPTER III. MY ADVENT ON MARS 19 CHAPTER IV. A PRISONER 31 CHAPTER V. I ELUDE MY WATCH DOG 41 CHAPTER VI. A FIGHT THAT WON FRIENDS 49 CHAPTER VII. CHILD-RAISING ON MARS 57 CHAPTER VIII. A FAIR CAPTIVE FROM THE SKY 65 CHAPTER IX. I LEARN THE LANGUAGE 75 CHAPTER X.CHAMPION AND CHIEF 81 CHAPTER XI. WITH DEJAH THORIS 95 CHAPTER XII. A PRISONER WITH POWER 105 CHAPTER XIII. LOVE-MAKING ON MARS 113 CHAPTER XIV. A DUEL TO THE DEATH 123 CHAPTER XV. SOLA TELLS ME HER STORY 137 CHAPTER XVI. WE PLAN ESCAPE 151 CHAPTER XVII. A COSTLY RECAPTURE 167 CHAPTER XVIII. CHAINED IN WARHOON 179 CHAPTER XIX. BATTLING IN THE ARENA 187 CHAPTER XX. IN THE ATMOSPHERE FACTORY 195 CHAPTER XXI. AN AIR SCOUT FOR ZODANGA 209 i ii CHAPTER XXII. I FIND DEJAH 223 CHAPTER XXIII. LOST IN THE SKY 237 CHAPTER XXIV. TARS TARKAS FINDS A FRIEND 247 CHAPTER XXV. THE LOOTING OF ZODANGA 259 CHAPTER XXVI. THROUGH CARNAGE TO JOY 267 CHAPTER XXVII. -

THE WARLORD of MARS 3 While the Allies Decided the Fate of the Conquered Nation

I was creeping in the shadows of the forest next to the Lost Sea of Korus. I was trailing a shadowy figure who hugged the darker places on the path, so I knew he was up to some kind of evil purpose. For six long Martian months I had not left the area around the hateful Temple of the Sun. My beautiful princess was trapped inside, far beneath the surface of Mars. I did not know whether she was alive or dead. Had Phaidor’s blade found the heart of the one I loved? Only time would reveal the truth. One entire Martian year—six hundred and eighty-seven Martian days—must come and go before the cell’s door would open again. Half of them had passed, but my last view into that cursed prison cell was still vivid. I saw the beauti- ful face of Phaidor, daughter of Matai Shang, 1 2 EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS distorted with jealous rage and hatred as she leaped toward my beautiful wife and princess with that long, sharp dagger. I saw the red girl, Thuvia of Ptarth, jump for- ward to prevent the hideous deed. But the smoke from the burning Temple of Issus blocked out the tragedy. My ears still rang with the single shriek as the knife fell. Then silence, and when the smoke cleared, the revolving temple had shut off all sight or sound from the chamber where the three beautiful women were imprisoned. There had been much to occupy my atten- tion since that terrible moment; but never for an instant had the memory faded. -

Reference Index to People, P Laces, and Things

Gathol and Tara of Helium, granddaughter of Helium, Greater Mars. JC & DT. Helium, Lesser Corinthian Umak of Arothol, commanded by Marna, younger daughter of John Carter and Horz (Orovarian) the lame jed Quarr-Tan at the Battle of the Galoom Reference Index to People, P laces, andThings Inath Dejah Thoris. Canal. Jahar Pan Dee Chee, an Orovar, and the recently Kamtool Corphal, a spirit, especially of the evil dead. Aanthor, an Orovarian Martian city, now long Pellucidar’s great jungle forest. Aul-don means Teetan Valley. deceased husband of Llana of Gathol. Koal Cosoom, Barsoomian name for the planet Venus. abandoned. “tailed men;” closely related to the Was-dons and Korad (Orovarian) Bolgani, a word meaning “gorilla” in the language Tara of Helium, wife of Gahan of Gathol, Cranston, Lamont, the alternate identity most Ho-dons of Africa’s Pal-ul-don. Kovasta Ackerman, Forrest J., 1916-2008, sent letter of of the great apes. daughter of JC & DT, mother of Llana of used by The Shadow. See Appendix K. warning to Doc Savage. aumble trees, found in the Valley Dor near the Gathol. Lothar Bowmen of Lothar, led by the odwar Kar Komak. Manator Cranston, Margo Lane, wife of The Shadow (see grazing plains of the plant men. Thuvia of Ptarth, married to Carthoris, Adik-Tar, an apothecary serving at Asoth-Naz in Marentina The Shadow). Breede, Adam, a Nebraskan writer, world traveler, possessor of a unique ability to control the palace of Klee Tun, the Holy Hekkador. Aun-ee-wan, an Aul-don tribe of the Great Forest.