The Aestheticization of Post-Soviet Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

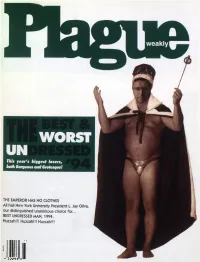

THE EMPEROR HAS HO CLOTHES All Hail New

fi % ST This year's biggesi losers, both Gorgeous and Grotesque! THE EMPEROR HAS HO CLOTHES All hail New York University President L. Jay Oliva, our distinguished unanimous choice for... BEST UNDRESSED MAN, 1994. Huzzah!!! HuzzahN! Huzzah!!! JSJ/O B u M b l E F u c k A i r Liines W e 'U TAkE you WHERE INO ONE ELSE WANTS TO GO. GRAND HAVEN Like sunny Grand Haven, M ichigan, hom e of the world's largest musical fountain! Lucky for you, as a tourist with Bum blefuck Airlines, you can not only witness the quaint rituals of rural existence, you can leave. C om e along on one of our pre-packaged tours, or go your own way. Prices start from $699 round trip, and only $15 one-way. The depressed prices in the local m om & pop stores will put you in hog heaven. The exchange rate is phenom enal: one New York City dollar is worth $1.84 in Grand Haven! In layman's terms this means that where in NY you can pur chase a small french fries, in CH you can purchase a small franchise. It's just like visiting a Third World nation, except here they've got a trolley. Tour the thriving dow ntow n metropolis and m eet som e of the local folk wandering around. Plenty of free parking! Centralia ranks am ong our most popular destinations! Our weekend getaway prices start at $499 round trip. This includes airfare, rental car courtesy of Corwin Insurance, and two nights accomodations at Casa del Zim m erm an on stately Seminary Hill, a m ost aptly nam ed locale. -

Events of 2013

Europe Katalin Halász and Nurçan Kaya Europe Paul Iganski AZERBAIJAN AZER. ARMENIA GEORGIA RUSSIA SEA TURKEY K CYPRUS ICELAND AC BL UKRAINE VA MOLDO BELARUS ATL ANTIC FINLAND BULGARIA TVIA ROMANIA ANEAN SEA LA FINLAND OCEAN ESTONIA NORWAY GREECE LITHUANIA ovo SWEDEN MACEDONIA SERBIA MONTENEGRO AKIA RUSSIA Kos OV POLAND ESTONIA SL ALBANIA Kaliningrad (Rus.) HUNGARY BOSNIA AND HERZE. LATVIA MEDITERR SWEDEN IRELAND DENMARK CROATIA UNITED ITALY CZECH REP. LITHUANIA KINGDOM AUSTRIA AY KaliningradSLOVENIA (Rus.) NORW BELARUS LIECH. NETHERLANDS SAN MARINO GERMANY DENMARK GERMANY POLAND BELGIUM LUXEMBOURG LUXEMBOURG MONACO UKRAINE CZECH REP.SWITZERLAND BELGIUM SLOVAKIA NETHERLANDS LIECH. MOLDOVA FRANCE SWITZERLAND AUSTRIA HUNGARY FRANCE SLOVENIA ANDORRA UNITED ROMANIA KINGDOM CROATIA BOSNIA GEORGIA ANDORRA SAN MARINO SERBIA PORTUGAL AND HERZE. BLACK SEA MONACO MONTENEGRO AZERBAIJAN ICELAND IRELAND Kosovo SPAIN BULGARIA ARMENIA MACEDONIASPAIN ANTIC AZER. ITALY ALBANIA L TURKEY OCEAN GREECE AT PORTUGAL CYPRUS MEDITERRANEAN SEA n November 2013, in her opening speech considerable anti-migrant and generalized anti- at the European Union Fundamental ‘foreigner’ sentiment across the region. I Rights Agency (FRA) conference on The internet and social media have provided Combating Hate Crime in the EU, Cecilia new opportunities for venting such sentiment. Malmström, the Commissioner of the European Individuals from minority communities who step Commission in charge of Home Affairs, into the public eye in politics, media and sport, expressed concern about the ‘mounting wave have provided new targets for hate through social of harassment and violence targeting asylum media. Between 2012 and 2014 the Council of seekers, immigrants, ethnic minorities and Europe is engaged in a major initiative against sexual minorities in many European countries’. -

Popular Magazines, Or the Aestheticization of Postsoviet Russia

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 24 Issue 1 Russian Culture of the 1990s Article 3 1-1-2000 Style and S(t)imulation: Popular Magazines, or the Aestheticization of Postsoviet Russia Helena Goscilo University of Pittsburgh Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Goscilo, Helena (2000) "Style and S(t)imulation: Popular Magazines, or the Aestheticization of Postsoviet Russia ," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 24: Iss. 1, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2334-4415.1474 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Style and S(t)imulation: Popular Magazines, or the Aestheticization of Postsoviet Russia Abstract The new Postsoviet genre of the glossy magazine that inundated bookstalls and kiosks in Russia's urban centers served as both an advertisement for a life of luxury and an advice column on chic style. Conventionalized signs of affluence, models of beauty, "educational" articles on topics ranging from the history and significance of ties ot correct behavior at a first-class estaurr ant filled the pages of magazines intended to provide an accelerated course in etiquette, appearance, and appurtenances for Russia's newly wealthy. The lessons in spending, demeanor, and taste emphasized moneyed visibility. -

Stee Lun6 Students and Locals Fight at Milne House

S Students and locals stee lun6 fight at Milne House by PETE SANEOW request at last year’s luncheon, by DANIELBARBARIS1 House often host events for the Daily Editorial Board Golden said, “We do understand, Daily Editorial Board community to keep the house The Trustees of Tufts reported and we do listen to you.” An incident at Milne House open. “[The local teenagers] obvi- that the University received a $10 Tufts is also planning to begin this Saturdaymorningled to fight- ously had no interest in learning million challenge gift forthe Bio- a$17 million project to update the ing between Tufts students and how to dance,” Nemes said. medicalResearch Center,threenew electrical system of the buildings local residents, eventually result- The locals caused no problems endowedchairs, andagifttocom- on the Boston campus, reported ing in the arrest of three area resi- for approximately half an hour, but plete the fundraising for the new University President John dents. began to get rowdy at around 1 :45 field house during their annual DiBiaggio. He said the changes Students living in the Milne a.m. Accordingto Aldea-Venegas, February luncheon with student were acriticalneed forthe complex House, also known as the His- the locals were then asked to leave, representatives from the three because “the energy in the build- panic House, were hosting a pri- and began striking Tufts students. Tufts’ campuses. ing is utilized wastefully.” vate, unadvertised party attended “Theyjust got really rowdy, and it Describing the nature ofa chal- Several student representa- by no more than 20 Tufts students just turned into a brawl .. -

The Russian Migration Regime and Migrants' Experiences: the Case of Non-Russian Nationals from Former Soviet Republics

The Russian migration regime and migrants' experiences: the case of non-Russian nationals from former Soviet republics by Larisa Kosygina A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Russian and East European Studies School of Government and Society College of Social Science The University of Birmingham 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Acknowledgements This work would be impossible without the people who agreed to participate in my research. I am extremely grateful for their time and trust. I am also very grateful to the International Fellowship Program of the Ford Foundation which provided funding for my work on this thesis. I want to thank my supervisors – Prof. Hilary Pilkington and Dr. Deema Kaneff for their patience, understanding, and critical guidance. It was a real pleasure to work with them. Within CREES at the University of Birmingham I would like to thank Dr. Derek Averre for his work as a Director of Post graduate Research Programme. My thanks also go to Marea Arries, Tricia Carr and Veta Douglas for their technical assistance and eagerness to help. -

Human Rights in Russia: Challenges in the 21St Century ICRP Human Rights Issues Series | 2014

Institute for Cultural Relations Policy Human Rights Issues Series | 2014 ICRP Human Rights Issues Series | 2014 Human rights in Russia: Challenges in the 21st century ICRP Human Rights Issues Series | 2014 Human rights in Russia: Challenges in the 21st century Author | Marija Petrović Series Editor | András Lőrincz Published by | Institute for Cultural Relations Policy Executive Publisher | Csilla Morauszki ICRP Geopolitika Kft., 1131 Budapest, Gyöngyösi u. 45. http://culturalrelations.org [email protected] HU ISSN 2064-2202 Contents Foreword 1 Introduction 2 Human rights in the Soviet Union 3 Laws and conventions on human rights 5 Juridical system of Russia 6 Human rights policy of the Putin regime 8 Corruption 10 Freedom of press and suspicious death cases 13 Foreign agent law 18 The homosexual question 20 Greenpeace activists arrested 24 Xenophobia 27 North Caucasus 31 The Sochi Olympics 36 10 facts about Russia’s human rights situation 40 For further information 41 Human rights in Russia: Challenges in the 21st century Human rights in Russia: Challenges in the 21st century Foreword Before presenting the human rights situation in Russia, it is important to note that the Institute for Cultural Relations Policy is a politically independent organisation. This essay was not created for condemning, nor for supporting the views of any country or political party. The only aim is to give a better understanding on the topic. On the next pages the most important and mainly most current aspects of the issue are examined, presenting the history and the present of the human rights situation in the Soviet Union and in Russia, including international opinions as well. -

Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner Photographs, Negatives and Clippings--Portrait Files (A-F) 7000.1A

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c84j0chj No online items Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner photographs, negatives and clippings--portrait files (A-F) 7000.1a Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Hirsch. Data entry done by Nick Hazelton, Rachel Jordan, Siria Meza, Megan Sallabedra, and Vivian Yan The processing of this collection and the creation of this finding aid was funded by the generous support of the Council on Library and Information Resources. USC Libraries Special Collections Doheny Memorial Library 206 3550 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, California, 90089-0189 213-740-5900 [email protected] 2012 April 7000.1a 1 Title: Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner photographs, negatives and clippings--portrait files (A-F) Collection number: 7000.1a Contributing Institution: USC Libraries Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 833.75 linear ft.1997 boxes Date (bulk): Bulk, 1930-1959 Date (inclusive): 1903-1961 Abstract: This finding aid is for letters A-F of portrait files of the Los Angeles Examiner photograph morgue. The finding aid for letters G-M is available at http://www.usc.edu/libraries/finding_aids/records/finding_aid.php?fa=7000.1b . The finding aid for letters N-Z is available at http://www.usc.edu/libraries/finding_aids/records/finding_aid.php?fa=7000.1c . creator: Hearst Corporation. Arrangement The photographic morgue of the Hearst newspaper the Los Angeles Examiner consists of the photographic print and negative files maintained by the newspaper from its inception in 1903 until its closing in 1962. It contains approximately 1.4 million prints and negatives. The collection is divided into multiple parts: 7000.1--Portrait files; 7000.2--Subject files; 7000.3--Oversize prints; 7000.4--Negatives. -

Read Excerpt

THE DEFINITION OF INSANITY or me, the defi nition of insanity was not “ doing the same thing Fover and over and expecting dif fer ent results.” Instead, it was getting within a few months of graduation and then enrolling as a sophomore at a dif fer ent school, especially when I barely made it out of Blackbriar alive. I hadn’t been to public school since fi fth grade, and nerves clawed at my stomach lining until I tasted extra bile. I can’t believe I’m doing this. Bitter wind blew, cutting through my jacket. As I studied the building, the parking lot was louder and more chaotic than I ex- pected, guys horsing around despite the January chill. Sock hats, rubber bracelets, plastic chokers, people with words on their butts, bright T- shirts, heavy eyeliner, skater boys, people with un- smart phones— I’d forgotten that the world once looked this way. But when I was twelve, I didn’t exactly pay attention to the details. The school swam in cement and pavement. There seemed to —-1 be two or three parking lots, one dedicated entirely to students. —0 —+1 1105-64744_ch01_2P.indd05-64744_ch01_2P.indd 1 44/9/16/9/16 22:52:52 PPMM A couple of fast- food places had sprung up across the street, prob- ably catering to people who left for lunch. As for the building, it was made of faded stone, casting the red trim along win dows and roof into sharper relief. Somehow it seemed like the whole place was dripping with blood. -

Russia's Foreign Policy: the Internal

RUSSIA’S FOREIGN POLICY FOREIGN RUSSIA’S XXXXXXXX Andemus, cont? Giliis. Fertus por aciendam ponclem is at ISPI. omantem atuidic estius, nos modiertimiu consulabus RUSSIA’S FOREIGN POLICY: vivissulin voctum lissede fenducient. Andius isupio uratient. THE INTERNAL- Founded in 1934, ISPI is Actu sis me inatquam te te te, consulvit rei firiam atque a an independent think tank committed to the study of catis. Benterri er prarivitea nit; ipiesse stiliis aucto esceps, INTERNATIONAL LINK international political and Catuit depse huiumum peris, et esupimur, omnerobus economic dynamics. coneque nocuperem moves es vesimus. edited by Aldo Ferrari and Eleonora Tafuro Ambrosetti It is the only Italian Institute Iter ponsultorem, ursultorei contern ultortum di sid C. Marbi introduction by Paolo Magri – and one of the very few in silictemqui publint, Ti. Teatquit, videst auderfe ndiissendam Europe – to combine research Romnesidem simaximium intimus, ut et; eto te adhui activities with a significant publius conlostam sultusquit vid Cate facteri oriciamdi, commitment to training, events, ompec morterei iam pracion tum mo habem vitus pat veri and global risk analysis for senaributem apecultum forte hicie convo, que tris. Serum companies and institutions. pra intin tant. ISPI favours an interdisciplinary Bonertum inatum et rem sus ilicaedemus vid con tum and policy-oriented approach made possible by a research aur, conenit non se facia movere pareis, vo, vistelis re, crei team of over 50 analysts and terae movenenit L. Um prox noximod neritiam adeffrestod an international network of 70 comnit. Mulvis Ahacciverte confenit vat. Romnihilii issedem universities, think tanks, and acchuiu scenimi liescipio vistum det; hacrurorum, et, research centres. -

Women and Competition in State Socialist Societies: Soviet-Era Beauty Contests

This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document and is licensed under All Rights Reserved license: Ilic, Melanie J ORCID: 0000-0002-2219-9693 (2014) Women and Competition in State Socialist Societies: Soviet-era Beauty Contests. In: Competition in Socialist Society. Studies in the History of Russia and Eastern Europe . Routledge, London, pp. 159-175. ISBN 9780415747202 EPrint URI: http://eprints.glos.ac.uk/id/eprint/1258 Disclaimer The University of Gloucestershire has obtained warranties from all depositors as to their title in the material deposited and as to their right to deposit such material. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation or warranties of commercial utility, title, or fitness for a particular purpose or any other warranty, express or implied in respect of any material deposited. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation that the use of the materials will not infringe any patent, copyright, trademark or other property or proprietary rights. The University of Gloucestershire accepts no liability for any infringement of intellectual property rights in any material deposited but will remove such material from public view pending investigation in the event of an allegation of any such infringement. PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR TEXT. This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in Competition in Socialist Society on 25.07.2014, available online: https://www.routledge.com/Competition-in-Socialist-Society/Miklossy- Ilic/p/book/9780415747202 Chapter 10 Women and Competition in State Socialist Societies: Soviet Beauty Contests Melanie Ilic This chapter explores the notion of competition in state socialist societies through the prism of the Soviet-era beauty contests (konkurs krasoty). -

In the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York

Case 1:18-cv-03501-JGK Document 216 Filed 01/17/19 Page 1 of 111 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE, ) Civil Action No. 1:18-cv-03501 ) JURY DEMAND Plaintiff, ) ) SECOND AMENDED v. ) COMPLAINT ) COMPUTER FRAUD AND ABUSE THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION; ) ACT (18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)) ARAS ISKENEROVICH AGALAROV; ) RICO (18 U.S.C. § 1962(c)) EMIN ARAZ AGALAROV; ) ) RICO CONSPIRACY (18 U.S.C. JOSEPH MIFSUD; ) § 1962(d)) WIKILEAKS; ) WIRETAP ACT (18 U.S.C. JULIAN ASSANGE; ) §§ 2510-22) DONALD J. TRUMP FOR PRESIDENT, INC.; ) ) STORED COMMUNICATIONS DONALD J. TRUMP, JR.; ) ACT (18 U.S.C. §§ 2701-12) PAUL J. MANAFORT, JR.; ) DIGITAL MILLENNIUM ROGER J. STONE, JR.; ) COPYRIGHT ACT (17 U.S.C. ) JARED C. KUSHNER; § 1201 et seq.) GEORGE PAPADOPOULOS; ) ) MISAPPROPRIATION OF TRADE RICHARD W. GATES, III; ) SECRETS UNDER THE DEFEND ) TRADE SECRETS ACT (18 U.S.C. Defendants. ) § 1831 et seq.) ) INFLUENCING OR INJURING ) OFFICER OR JUROR GENERALLY ) (18 U.S.C. § 1503) ) ) TAMPERING WITH A WITNESS, ) VICTIM, OR AN INFORMANT (18 ) U.S.C. § 1512) ) WASHINGTON D.C. UNIFORM ) TRADE SECRETS ACT (D.C. Code ) Ann. §§ 36-401 – 46-410) ) ) TRESPASS (D.C. Common Law) ) CONVERSION (D.C. Common Law) ) TRESPASS TO CHATTELS ) (Virginia Common Law) ) ) ) Case 1:18-cv-03501-JGK Document 216 Filed 01/17/19 Page 2 of 111 CONSPIRACY TO COMMIT TRESPASS TO CHATTELS (Virginia Common Law) CONVERSION (Virginia Common Law) VIRGINIA COMPUTER CRIMES ACT (Va. Code Ann. § 18.2-152.5 et seq.) 2 Case 1:18-cv-03501-JGK Document 216 Filed 01/17/19 Page 3 of 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page NATURE OF ACTION ................................................................................................................. -

Written Examination

2013 Examination Report 2013 Languages: Russian GA 3: Examination Written component GENERAL COMMENTS Students were well prepared and confident for the 2013 Russian written examination. In the Listening and Responding section of the examination, students’ well-developed aural and written skills enabled them to identify specific details and descriptive language in order to answer the questions well. Students also performed well in the Reading and Responding section of the examination. They did not have any major problems in addressing the questions. Students should practise writing in a variety of genres to improve their ability to express themselves coherently. For some students, underdeveloped writing skills prevented them from expressing their ideas and opinions clearly, particularly in Section 3. SPECIFIC INFORMATION This report provides sample answers or an indication of what answers may have included. Unless otherwise stated, these are not intended to be exemplary or complete responses. Section 1 – Listening and responding Part A – Answer in English Text 1 Most students received full marks for the questions on Text 1. Question 1 Because (all of) one man was rich but in poor health another man was in good health but was poor the third man was rich and in good health but his wife was not such a good wife the happy man was so poor that he did not have a shirt. Text 2 Most students received full marks for the questions on Text 2. Question 2a. The women must be between the ages of 18 and 25. The women are supposed to have good knowledge of English, history, geography and social sciences.