A Report on Groundwater Conditions in the Bongaigaon and Biswanath Districts of Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ST (1F!L!) PUBLIC WORI{S ROADS DEPARTMENT (PWRD) ::ESTABLISHMENT-& BRANCH IANATA BHAWAN :: DISPUR ::GUWAHATI-781006

GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM ~ fcfm'T ~ST (1f!l!) PUBLIC WORI{S ROADS DEPARTMENT (PWRD) ::ESTABLISHMENT-& BRANCH IANATA BHAWAN :: DISPUR ::GUWAHATI-781006 ORDERS BY THE GOVERNOR OF ASSAM NOTIFICATION Dated Di spur, th e 5th Jun e, 202 1 No . RBEB .116/2019/ Pt-l/ 76: In the interest of public service, the Governor of Assam is pleased to reorgani ze a nd rena me the existing Circles of the Public Works Ro ads Department, including the 4(four) newly created Circle Offi ces, a long with the respective Divi sions unde r their jurisdi ction (excluding the Si xth Schedule Di stricts) as pe r a rrangement show n below w.e.f. the da te of issue of this noti fica tion: Sl. Existing Na m e Renam ed Circle Jurisdiction Name of Divisions under the Renam ed Circle of Dis tr ict 1. Guwahati Roa d Kamrup Road Circle Ka mrup 1. So uth Kamrup Territo rial Road Div isio n Circle H.Q . : Guwahati (Rural) 2. Jalukbari & Hajo Territori al Road Divis ion H.Q. : Guwahati 3. Brahmaputra Bridge Construction Division 2. Guwahati AR IAS P City Road Circle Kamrup 1. East Guwahati Territori al Road Division Circle H.Q.: Gu wahati (Metro) 2. Di spur Territori al Ro ad Di vision H.Q. : Guwahati 3. West Guwahati Territori al Road Division 3. Nalbari Road Na lb ari Ro ad Ci rcle Na lba ri 1. Na lb ari Di stri ct Territori al Road Division Circle H.Q. : Na lbari H.Q. : Nalba ri 4. Western Assa m Goa l para & So uth Goal pa ra & 1. -

LIST of POST GST COMMISSIONERATE, DIVISION and RANGE USER DETAILS ZONE NAME ZONE CODE Search

LIST OF POST GST COMMISSIONERATE, DIVISION AND RANGE USER DETAILS ZONE NAME GUW ZONE CODE 70 Search: Commission Commissionerate Code Commissionerate Jurisdiction Division Code Division Name Division Jurisdiction Range Code Range Name Range Jurisdiction erate Name Districts of Kamrup (Metro), Kamrup (Rural), Baksa, Kokrajhar, Bongaigon, Chirang, Barapeta, Dhubri, South Salmara- Entire District of Barpeta, Baksa, Nalbari, Mankachar, Nalbari, Goalpara, Morigaon, Kamrup (Rural) and part of Kamrup (Metro) Nagoan, Hojai, East KarbiAnglong, West [Areas under Paltan Bazar PS, Latasil PS, Karbi Anglong, Dima Hasao, Cachar, Panbazar PS, Fatasil Ambari PS, Areas under Panbazar PS, Paltanbazar PS & Hailakandi and Karimganj in the state of Bharalumukh PS, Jalukbari PS, Azara PS & Latasil PS of Kamrup (Metro) District of UQ Guwahati Assam. UQ01 Guwahati-I Gorchuk PS] in the State of Assam UQ0101 I-A Assam Areas under Fatasil Ambari PS, UQ0102 I-B Bharalumukh PS of Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Gorchuk, Jalukbari & Azara PS UQ0103 I-C of Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Nagarbera PS, Boko PS, Palashbari PS & Chaygaon PS of Kamrup UQ0104 I-D District Areas under Hajo PS, Kaya PS & Sualkuchi UQ0105 I-E PS of Kamrup District Areas under Baihata PS, Kamalpur PS and UQ0106 I-F Rangiya PS of Kamrup District Areas under entire Nalbari District & Baksa UQ0107 Nalbari District UQ0108 Barpeta Areas under Barpeta District Part of Kamrup (Metro) [other than the areas covered under Guwahati-I Division], Morigaon, Nagaon, Hojai, East Karbi Anglong, West Karbi Anglong District in the Areas under Chandmari & Bhangagarh PS of UQ02 Guwahati-II State of Assam UQ0201 II-A Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Noonmati & Geetanagar PS of UQ0202 II-B Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Pragjyotishpur PS, Satgaon PS UQ0203 II-C & Sasal PS of Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Dispur PS & Hatigaon PS of UQ0204 II-D Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Basistha PS, Sonapur PS & UQ0205 II-E Khetri PS of Kamrup (Metropolitan) District. -

PROCUREMENT PLAN(Textual Part)

PROCUREMENT PLAN(Textual Part) Project information: INDIA, Assam Agribusiness and Rural Transformation Project (APART) Public Disclosure Authorized Project Implementation agency: Assam Rural Infrastructure and Agricultural Services Society (ARIASS)is the main agency. Date of the Procurement Plan:October 01, 2019 Period covered by this Procurement Plan:Until publication of next version of the Procurement Plan. Preamble In accordance with paragraph5.9 of the “World Bank Procurement Regulations for IPF Borrowers” (July 2016, Revised November 2017 and August 2018) (“Procurement Regulations”)the Bank’s Systematic Public Disclosure Authorized Tracking and Exchanges in Procurement (STEP) system will be used to prepare, clear and update Procurement Plansand conduct all procurement transactions for the Project. This textual part along with the Procurement Plan tables in STEPconstitute the Procurement Plan for the Project.The following conditionsapply to all procurement activities in the Procurement Plan. The other elements of the Procurement Plan as required under paragraph 4.4 of the Procurement Regulations are set forth in STEP. The Bank’s Standard Procurement Documents: shall be used for all contracts subject to international competitive procurement and those contracts as specified in the Procurement Plan tables in STEP. Public Disclosure Authorized Procurement for the project will be carried out in accordance with the World Bank’s Procurement Regulations for IPF Borrowers, July 2016, Revised November 2017 and August 2018 and applicable to Investment Project Financing (IPF). The project will be subject to the World Bank’s Anticorruption Guidelines, dated October 15, 2006, as revised in January 2011 and July 2016. Public Disclosure Authorized The table below describes various procurement methods to be used for activities financed by the loan. -

Political Science (Diphu)

Data on Mentors-Maintees of the Department of Political Science, Assam University Diphu Campus Name of Mentor: Dr. Niranjan Mohapatra Course No. 405 (Project Work) of the P.G Syllabus, Period: May-2017 SERIAL NAME OF THE STUDENT DISSERTION TOPIC NO 1 Buddhoram Ronghang Karbi Society and Culture : Case Study taralangso 2 Hunmily Kropi Social Status of Karbi: Women: A Case Study of Plimplam Langso Village, Diphu 3 Happy Gogoi Impact of Mid Day Meal on Lower Primary Schools: A Case Study in Selenghat Block Area of Jorhat District 4 Porismita Borah The Functioning of Janani Surakha Yojana 5 Dibyamohan Gogoi Student’s issue: A Case Study of Assam University, Diphu Campus 6 Rishi Kesh Gogoi A Case Study on Lack of Proper Infrastructer in Assam University, Diphu Campus 7 Rustom Rongphar Importance of Bamboo in Karbi Society 8 Mirdan rongchohonpi The Social Status of Women in Karbi Society 9 Birkhang Narzary Domestic Violence Against Women: A Case Study of Rongchingbar Village , Diphu 10 Monjit Timungpi Health Awareness Among the karbi Women: A Case Study of Serlong Village of Karbi Anglong District, Assam 11 Krishna Borah Socio- Economic Condition of Women in Tea Graden: A Case Study of Monabari Tea Estate of Biswanath District of Assam 12 Achyut Chandra Borah Student’s Issue: A Case Study of Assam University, Diphu Campus 13 Jita Engti Katharpi Women Empowerment Through Self Help Group: A Case Study Under Koilamati Karbianglong District , Assam 14 Dipika Das Role of Self Help Group As A Tool For Empowerment of Women: A Case Study of Uttar Barbill -

Tezpur Building Division

Thecom Statement showing the flagship programs currently operational and some of completed works under P.W.D., Tezpur Building Division : Tezpur *Name of work :- Construction of Girls' Hostel at Pavoi High School in Biswanath District (Gr. No. - 49). *Year of sanction : 2012 *Sanction Amount : Rs. 155.35 (L) *Physical progress : - 100% *Financial progress :- Rs. 12005173.00 *Name of work :- Construction of Additional Class Room 1 (One) No. under Multi Sectoral Development Programme (MSDP) in Biswanath District for the year 2015-16 at :- Golia Gerenta LPS *Year of sanction : 2015-16 *Sanction Amount : 4.80 L *Physical progress : - 100% *Financial progress :- Rs. 213840.00 *Name of work :- Improvement of Public facilities including Public Toilet in SDO (C) Office premises at Biswanath Chariali. *Year of sanction : 2017 * Sanction Amount : Rs. 1744500.00 *Physical progress : - 100% *Financial progress :- Nil *Name of work :- Construction of Barrack for Security Personnel at Judicial Officers Qtrs. at Biswanath Chariali. *Year of sanction : 2017-18 * sanction Amount : Rs.1366500.00 *Physical progress : - 100% *Financial progress :- Rs. 1352342.00 *Name of work :- Construction of Girls' Hostel at Janata H.S. School campus under Bihali Block in Sonitpur District. (Gr. No. - 47) *Year of sanction : 2012 * Sanction Amount : Rs. 155.35 (L) *Physical progress : - 100% *Financial progress :- Rs. 9237826.00 *Name of work :- Construction of Garage for Mobile Kit Van received from Govt. of India in the office of the Inspector of Legal Metrology, Biswanath Chariali during the financial year 2016-17 under Plan scheme. *Year of sanction : 2016-17 * Sanction Amount : 4.452 L *Physical progress : - 100% *Financial progress :-Rs. -

Goupur a Karbi Arat Atum Pen Mei Kangni

The Sentinel PAGE 21 KARBI Guwahati, 03rd August, 2018 Measles pen Rubella vaccine Paipai 17 arni EM Rupsing Teron KAAC pen osomar atum aphan ingprim kipi chengpo Land & Revenue arpu kedeng ningkan hini angbong ongdung medu kelong ason son akeso pavir pen non Jakhong an po, India adangpi along angbong Land & Rev- non M-R vaccine enue asaikam pen kado ingprim kipiji aphan kave sika 5,58,20,219 bang 41 crore aosomar medu longlo. Lasi atum aphan kemang kedamtang ningkan isi (Target) do. Laso lapen EM Rupsing angbong pen Karbi Teron ahut pangbar lote Anglong angkang phant pli sose abat aphan pangrumpet longlo. bang 3,36,000 Chiklo jon pli angbong aosomar atum aphan jongsi la-an medu bangso M-R vaccine kelong pulote ningkan isi ingprim kipiji aphan angbong chesik do lo. Laso asai sika Crore 20 sose along kaprek kaprek a Land & Revenue DIPHU: Detpi adang akeso, khok-it, mek- aphan Measles pen Ru- pangrumpet 2,21,719 block along kedo DIPHU: Karbi Anglong along medu kelong asaikam pen medu along jasemet osomar keso, aphukeso pen bella vaccine ingprim kipi do, lasi, lahei aosomar ANM, ASHA, Autonomous Council jumheksi thek long. kelongji angring do lo. arta chiklo jon nerkep chenglok oso aphili ahut ajoine thangnat akeso atum aphan school Anganwadi atum kaparlo saikam 30 Kedamtang 2017-18 Laso aphuthak pen arta ningkan krepho ason son akeso pen mate akisung ave pinlo ahem along damsi cherap dun po lapen angbong edu kelong ke- dihin aningkan anta pherangke pen EM adak ason son akeso pajok un ajakong do, pusi angthek long lo. -

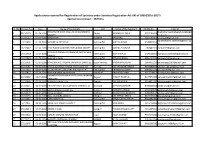

Applications Received for Registration of Societies (2016-2017).Pdf

Applications received for Registration of Societies under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 (2016-2017) Applications recieved = 4209 Nos. Sl. No. Receipt No. Date Name of the Society Dist Name of the Applicant Mobile No. Email ID JHAGRAPAR NAVA KALLYAN DEVELOPMENT jhagrarparnavakallyandvsociety@g 1 08210379 01-04-2016 Dhubri ASHRAFUL HOQUE 9957186659 SOCIETY mail.com 2 12210127 01-04-2016 SOROIWATI Golaghat RAJIB DAS 9859769391 [email protected] [email protected] 3 15211430 01-04-2016 SURAKSHA INITIATIVE Kamrup (M) AMIT SHARMA 9508817613 m 4 15211447 01-04-2016 DHALBOMA SMASHAN PARISALANA SAMITY Kamrup (M) SUBHAS TUMUNG 967882322 [email protected] SRI SRI DAKSHINA KALI MANDIR PARISALANA 5 15211448 01-04-2016 Kamrup (M) DILIP TAMULI 9435116097 [email protected] SAMITY 6 15211449 01-04-2016 WAS BIPU CLUB Kamrup (M) BITUPAN RANGI 8486165594 [email protected] 7 30210001 01-04-2016 MANDIRA N.C. KRISHAK UNNAYAN SAMITTEE South Kamrup ANOWAR HUSSAIN 9864072234 [email protected] 8 06210182 02-04-2016 DHULA ANCHALIK KRISAK JYOTI SAMITTEE Darrang MAHIRUDDIN AHMED 9859586820 [email protected] 9 15211450 02-04-2016 YOUNG PEOPLE WELFARE FOUNDATION Kamrup (M) PRANAB KR SAIKIA 9864412276 [email protected] 10 19210437 02-04-2016 RAMAKRISHNA SEVASHRAM Kokrajhar PRADIP KR SAHA 9957724665 [email protected] DABAKA PATHER AMORJYOTI YUBA UNNAYAN 11 22210668 02-04-2016 Nagaon ANWAR HUSSAIN 8724871287 [email protected] PARISHAD 12 22210669 02-04-2016 ROYAL FOUNDATION Nagaon RAIHAN UDDIN 8724871287 [email protected] -

On Legal Literacy: Rights, Access and It’S Utility in Present Context

REPORT ON LEGAL LITERACY: RIGHTS, ACCESS AND IT’S UTILITY IN PRESENT CONTEXT REPORT ON LEGAL LITERACY: RIGHTS, ACCESS AND IT’S UTILITY IN PRESENT CONTEXT State Resource Centre Assam Mandovi Apartments GNB Road, Ambari, Guwahati – 781001 Website : srcguwahati.co.in :: Email : [email protected] 1 REPORT ON LEGAL LITERACY: RIGHTS, ACCESS AND IT’S UTILITY IN PRESENT CONTEXT CONTENTS: Page No. 1. Introduction 3 2. Background Analysis of the Project 3 3. Objectives of the Project 5 4. Summary of the Proposed activities 5 5. Strategy Adopted 6 6. Executive Summery 13 7. Report of activity 13 8. Interactive Meeting 62 9. Installation of Hoardings 71 10. Development and Printing of IEC materials 73 11. Jatha Programme 73 12. Name Casting 78 13. Periodic Review Meeting 78 14. Outcomes of the Project 80 15. Constrains and Challenges 81 16. Best Practices 82 17. Annexure i) Scan Copy of IEC materials 85 ii) List of Participants 91 iii) Programme Schedule 102 iv) Certificate 104 v) Feedback Format 105 vi) Paper Cutting 106 vii) Comparative Status 107 viii) Evaluation Questionnair 111 ix) Feedback format for Training 113 x) Post Evaluation Format 114 xi) Pre test and Post Test 115 2 REPORT ON LEGAL LITERACY: RIGHTS, ACCESS AND IT’S UTILITY IN PRESENT CONTEXT 1. INTRODUCTION: State Resource Centre Assam (SRC) is the institution established by MHRD (Ministry of Human Resource Development) through Centre Sector Scheme, ‘Scheme of Support to Voluntary Agencies for Adult Education & Skill Development’ under the aegis of leading VOs (Voluntary Organizations) with proven record of success in the social sector to provide technical & academic support to Adult Education Programme in the concerned state. -

SAMAGRA SHIKSHA (SECONDARY), ASSAM Kahilipara, Guwahati-781019

OFFICE OF THE MISSION DIRECTOR SAMAGRA SHIKSHA (SECONDARY), ASSAM Kahilipara, Guwahati-781019 No. RMSA/CW/NR/19-20/1207/2019/49 Dated-Guwahati the 08-01-2020 NOTICE INVITING E-TENDER The Mission Director, Samagra Shiksha, Assam invites bids for the following school building works from registered contractor under PWD (Building), Assam having experience of similar nature of work in Assam. Details of the bid may be seen at e-procurement portal website i.e. www.assamtenders.gov.in and also in the office of the undersigned during office hours from 30-01-2020 (1100 hours) to 21-02-2020 (1400 hours). The bidders must be enrolled in www.assamtenders.gov.in Name of work: Construction for Approximate Time of various civil work interventions Earnest Money Deposit value of work completion Package for strengthening of existing Tender Sl no. secondary schools under cost Samagra Shiksha, Assam Reserved (Rs. in lakh) (in month) General at…… category RMSA/CW/ JDSSB High School in Barpeta 1 34.04 10 Rs. 68,080/- Rs. 34,040/- Rs. 3,000/- 19-20/1 district RMSA/CW/ Mandia Girls High School in 2 51.90 10 Rs. 1,03,800/- Rs. 51,900/- Rs. 3,000/- 19-20/2 Barpeta district RMSA/CW/ Shawrachara H.S. School in 3 30.20 10 Rs. 60,400/- Rs. 30,200/- Rs. 3,000/- 19-20/3 Barpeta district RMSA/CW/ Joymati High School in 4 48.90 10 Rs. 97,800/- Rs. 48,900/- Rs. 3,000/- 19-20/4 Biswanath district RMSA/CW/ Dinabandhu High School in 5 45.72 10 Rs. -

SERVICE AREA VILLAGE LIST for SONITPUR and BISWANATH DISTRICT

SERVICE AREA VILLAGE LIST for SONITPUR AND BISWANATH DISTRICT COMPILLED BY LEAD BANK OFFICE SONITPUR AND BISWANATH DISTRICT UCO BANK TEZPUR,ASSAM PIN 784001 SERVICE AREA VILLAGES UNDER PUB CHAIDUAR DEV.BLOCK TOTAL NO. OF BANKS :8 TOTAL NO. OF VILLAGES :357 Banks Sl Villages Gaon Panchayat Remarks No. 1.A.G.V. Bank 1 Aliguri Pub Kalabari Hawajan Branch 2 Aliguri Pichola Subansiri (Part) 3 Amguri Pichola Subansiri(Part) 4 Bejiachuk Pub Kalabari 5 Borachuk Dakhin Kalabari(Part) 6 Borachuk Kaibarta Dakhin Kalabari(Part) 7 Brahmangaon Pub Kalabari 8 Chapori Pichola Subansiri(Part) 9 Chengmaraguri Kalabari(Part) 10 Dakchaporib Kaibarta Pichola Subansiri(Part) 11 Deurichukgaon Pub Kalabari 12 Deurigaon Pub Kalabari 13 Dharakara Pichola Subansiri(Part) 14 Dologuri Dakhin Kalabari(Part) 15 Gamariati Pichola Subansiri(Part) 16 Ghuriagaon Pub Kalabari 17 Gitang Pichola Subansiri(Part) 18 Jokhinichuk Dakhin Kalabari(Part) 19 Kalitagaon Kalabari(Part) 20 Kardongchuk Pichola Subansiri(Part) 21 KHaraiguri Pub Kalabari 22 Khutikatia gaon Pub Kalabari 23 Kukurashowa Kalabari(Part) 24 Maj Pichala Pichola Subansiri(Part) 25 Mohkhali Pichola Subansiri(Part) 26 No.1 Dola Dakhin Kalabari(Part) 27 No.1 Satiara Pub Kalabari 28 No.2 Deurigaon Pub Kalabari 29 No.2 Dalla Doloni Kalabari(Part) 30 No.1 Kolmouguri Sessa Asomiya Kalabari(Part) 31 Nopamua Pub Kalabari 32 Pichala Dakchapori Pichola Subansiri(Part) 33 Pichalamukh Pub Kalabari 34 Salamora Dakhin Kalabari(Part) 35 Satiara Pichola Subansiri(Part) 36 Satiara Pathar Pub Kalabari 37 Sowaguri Pichola Subansiri(Part) 38 Sutargaon Pub Kalabari 39 Tamulibheti Pub Kalabari Banks Sl Villages Gaon Panchayat Remarks No. 2. A.G.V. -

Pre-Feasibility Report

Pre-Feasibility Report For Proposed Construction of four lane TBM TUNNEL including approaches under River Brahmaputra between Gohpur on NH-52 North Bank and Numaligarh on NH-37 South Bank, Assam (Length: 34.664 km) on EPC Mode under SARDP-NE Phase-A Project Proponent “National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd. (NHIDCL)” Prepared By National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd. Pre-Feasibility Report - Proposed Construction of four lane TBM TUNNEL including approaches under River Brahmaputra between Gohpur on NH-52 North Bank and Numaligarh on NH-37 South Bank, Assam (Length: 34.664 km) on EPC Mode under SARDP-NE Phase-A TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION OF PROJECT/BACKGROUND INFORMATION ............................. 2 2.1 Identification of Project & Project Proponent .................................................................. 2 2.2 Description of Nature of Project ....................................................................................... 2 2.3 Need for the project .......................................................................................................... 3 2.4 Demand & Supply Gap ..................................................................................................... 4 2.5 Import vs Indigenous Production ..................................................................................... 4 2.6 Export Possibilities .......................................................................................................... -

Total Draft Elector-2017

Assembly Constituency wise report of the Draft Electoral Roll, 2017 in the State of Assam as on 14-10-2016 Assembly Constituency General Electors No. Name Male Female 3rd Total Gender 1 RATABARI (SC) 77,248 68146 0 145,394 2 PATHARKANDI 82,251 72350 1 154,602 3 KARIMGANJ NORTH 88,995 81644 0 170,639 4 KARIMGANJ SOUTH 84,094 75617 0 159,711 5 BADARPUR 72,123 66421 0 138,544 Karimganj District 404,711 364,178 1 768,890 6 HAILAKANDI 76,789 69068 6 145,863 7 KATLICHERRA 83,041 74364 2 157,407 8 ALGAPUR 78,260 66329 0 144,589 Hailakandi District 238,090 209,761 8 447,859 9 SILCHAR 104,181 101861 18 206,060 10 SONAI 82,365 75966 8 158,339 11 DHOLAI (SC) 85,241 74637 2 159,880 12 UDHARBOND 73,011 66552 13 139,576 13 LAKHIPUR 74,950 67878 17 142,845 14 BARKHOLA 67,798 61101 11 128,910 15 KATIGORA 84,648 75448 9 160,105 Cachar District 572,194 523,443 78 1,095,715 16 HAFLONG (ST) 64,086 62312 0 126,398 Dima Hasao District 64,086 62,312 0 126,398 17 BOKAJAN (ST) 67,076 62770 7 129,853 18 HOWRAGHAT (ST) 59,349 57864 0 117,213 19 DIPHU (ST) 87,529 84154 5 171,688 Karbi Anglong District 213,954 204,788 12 418,754 20 BAITHALANGSO (ST) 93,348 86771 0 180,119 West Karbi Anglong District 93,348 86,771 0 180,119 21 MANKACHAR 92,908 89846 4 182,758 22 SALMARA SOUTH 81,486 76049 2 157,537 South Salmara District 174,394 165,895 6 340,295 23 DHUBRI 89,369 82796 4 172,169 24 GAURIPUR 92,968 86061 1 179,030 25 GOLAKGANJ 93,197 83765 0 176,962 26 BILASIPARA WEST 75,423 71558 0 146,981 27 BILASIPARA EAST 94,835 90491 1 185,327 Dhubri District 445,792 414,671 6