Tennessee Gas Pipeline, L.L.C. Docket No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company, L.L.C. 191 Ibla 80

TENNESSEE GAS PIPELINE COMPANY, L.L.C. 191 IBLA 80 Decided September 11, 2017 United States Department of the Interior a Office of Hearings and Appeals a Interior Board of Land Appeals 801 N. Quincy St., Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22203 703-235-3750 703-235-8349 (fax) TENNESSEE GAS PIPELINE COMPANY, L.L.C. 2014-266, et al. Decided September 11, 2017 Appeal from orders determining that Outer Continental Shelf pipeline right-of-way grants had expired and ordering that their associated pipelines be decommissioned. 01684, et al. Affirmed. 1. Rights-of-Way: Oil and Gas Pipelines; Oil and Gas: Pipelines; Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act: Rights-of-Way The Secretary is authorized to grant pipeline rights-of-way through the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) for transporting oil, natural gas, or other minerals. However, the design, construction, maintenance, and operation of transporter- operated pipelines on the OCS are subject to standards established by the Department of Transportation (DOT), and regulation by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Where FERC grants a certificate of public convenience and necessity to an OCS pipeline under the Natural Gas Act, it can be abandoned only after authorized to do so by FERC, and if it loses its certificate of public convenience and necessity, such a pipeline can no longer be used to transport gas on the OCS. APPEARANCES: David M. Hunter, Esq. and Tyler J. Rench, Esq., Jones Walker, LLC, New Orleans, Louisiana, for the appellant; Eric Andreas, Esq., U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of the Solicitor, Washington, DC, for the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement. -

Pipelines in the Southeast US

Pipelines in the Southeast US: The Backbone of America’s Energy Independence For NASEO - Southeast Region Edward O'Brien Tuesday, April 23, 2019 Technology – New drilling techniques allow more production - Fracking Big Data – Processing and storage solutions and the development of new devices to track a wider array of reservoir, machinery and personnel performance Seismic – Lowered finding costs and allowed exploration for reserves not locatable by other means 3-D Modeling – Better able to recreate oil assets in three dimensions, allowing companies to better map underground caverns and target specific areas rich with What Happened? hydrocarbons How Much Has Changed Since Y2K? US Natural Gas Production (MMCF) US Oil Production (Billion Barrels) 33000 4 31000 3.5 29000 27000 3 25000 2.5 23000 21000 2 19000 17000 1.5 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 How Do Hydrocarbons Move? Pipelines are the safest and most efficient way to hydrocarbons US Highlights: - More than 300,000 miles of natural gas transmission pipeline - More than 2.1 million miles of distribution pipeline - More than 25 Tcf natural gas moved via pipeline in 2017 - 72,000 miles of crude pipelines - 63,000 miles of refined product pipeline - US DOT regulates pipeline safety • Gathering – gather raw natural gas from production wells and transport it to large cross-country transmission pipelines • Transmission – transport natural gas thousands of miles from processing facilities across many parts of the continental United States • Distribution – distribute natural gas to homes and businesses through large distribution lines mains and service lines. -

NYCA Pipeline Congestion and Infrastructure Adequacy Assessment

NYCA Pipeline Congestion and Infrastructure Adequacy Assessment New York Independent System Operator September, 2013 REDACTED 100 SUMMER STREET, SUITE 3200 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02110 TEL 617-531-2818 FAX 617-531-2826 LIMITATION ON LIABILITY This report has been prepared for NYISO for the sole purpose of assessing the adequacy of the natural gas infrastructure in regard to meeting the fuel delivery needs of gas-fired generation in NYISO. Input parameters to various models are based largely on actual public data from the pipelines and local distribution companies operating in New York State. Findings contained herein depend on the assumptions identified in our report, including the mathematical models used to determine historic congestion levels and flow balances over the study period. Levitan & Associates, Inc. believes these assumptions to be reasonable. However, there is no assurance that any specific set of assumptions associated with new pipeline and storage projects will be encountered. DISCLAIMER This report was prepared by Levitan & Associates, Inc. (LAI) for the New York Independent System Operator, Inc. (NYISO). The views and conclusions expressed in this study represent those of LAI and do not necessarily represent those of the NYISO. No official endorsement by the NYISO is intended or should be inferred. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... -

Investor Presentation Acquisition of El Paso Corporation October 16, 2011

Investor Presentation Acquisition of El Paso Corporation October 16, 2011 IMPORTANT ADDITIONAL INFORMATION WILL BE FILED WITH THE SEC Kinder Morgan, Inc. (“KMI”) plans to file with the SEC a Registration Statement on Form S-4 in connection with the proposed transaction, and KMI and El Paso Corporation (“EP”) plan to file with the SEC and mail to their respective stockholders a Joint Proxy/Information Statement/Prospectus in connection with the proposed transaction. THE REGISTRATION STATEMENT AND THE JOINT PROXY/INFORMATION STATEMENT/PROSPECTUS WILL CONTAIN IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABOUT KMI, EP, THE PROPOSED TRANSACTION AND RELATED MATTERS. INVESTORS AND SECURITY HOLDERS ARE URGED TO READ THE REGISTRATION STATEMENT AND THE JOINT PROXY/INFORMATION STATEMENT/PROSPECTUS CAREFULLY WHEN THEY BECOME AVAILABLE. Investors and security holders will be able to obtain free copies of the Registration Statement and the Joint Proxy/Information Statement/Prospectus and other documents filed with the SEC by KMI and EP through the web site maintained by the SEC at www.sec.gov. In addition, investors and security holders will be able to obtain free copies of the Registration Statement and the Joint Proxy/Information Statement/Prospectus by phone, e-mail or written request by contacting the investor relations department of KMI or EP at the following: Kinder Morgan, Inc. El Paso Corporation Address: 500 Dallas Street, Suite 1000 1001 Louisiana Street Houston, Texas 77002 Houston, Texas 77002 Attention: Investor Relations Attention: Investor Relations Phone: (713) 369-9490 (713) 420-5855 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] PARTICIPANTS IN THE SOLICITATION KMI and EP, and their respective directors and executive officers, may be deemed to be participants in the solicitation of proxies in respect of the proposed transactions contemplated by the merger agreement. -

Failure Investigation Report - Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co

DOT US Department of Transportation PHMSA Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration OPS Office of Pipeline Safety Southwest Region Principal Investigator Gene Roberson , I! Region Director R.M.seeley ~~ Date of Report 7/31/2011 Subject Failure Investigation Report - Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co. - Internal Corrosion Operator, location, & Consequences Date of Failure 12/08/2010 Commodity Released Natural Gas City/County & State East Bernard/Wharton County, TX OplD & Operator Name 19160 Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co Unit # & Unit Name 4084 Cleveland District SMART Activity # 132408 Milepost / Location Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co ., Station 17, East Bernard, TX Type of Failure Internal corrosion in lateral connecting to station discharge header Fatalities o Injuries o Description of area Operator's facility only. impacted Property Damage $ 715,000 Failure Investigation Report – Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co. ‐ Internal Corrosion Failure Date 12/08/2010 Executive Summary On December 8, 2010, Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company made a notification to the National Response Center reporting a natural gas release on their Tennessee Gas Pipeline (TGP) 100 system. Upon review of the information an investigator from the Southwest Region was dispatched to the accident site the following day. At approximately 4:25 pm CST, December 8, 2010, TGP identified a release of natural gas in the discharge header area of the TGP Station 17, System 100, at East Bernard, TX. The failed pipe consisted of 24” diameter, 0.500” wall, X‐40(40,000 SMYS) lateral that connected to the station discharge header piping. PThe TG system is monitored by gas control in Houston, Texas and the station ESD was activated immediately when the incident occurred. -

Transporting Natural Gas

About U.S. Natural Gas Pipelines – Transporting Natural Gas The U.S. natural gas pipeline network is a highly U.S. Natural Gas Pipeline Network integrated transmission and distribution grid that can transport natural gas to and from nearly any location in the lower 48 States. The natural gas pipeline grid comprises: • More than 210 natural gas pipeline systems. • 300,000 miles of interstate and intrastate transmission pipelines (see mileage table). • More than 1,400 compressor stations that maintain pressure on the natural gas pipeline network and assure continuous forward movement of supplies (see map). • More than 11,000 delivery points, 5,000 click to enlarge receipt points, and 1,400 interconnection See Appendix A: Combined ‘Natural Gas points that provide for the transfer of natural Transportation’ maps gas throughout the United States. • 29 hubs or market centers that provide See Appendix B: Tables additional interconnections (see map). • 394 underground natural gas storage facilities (see map). Geographic Coverage of Pipeline Companies • 55 locations where natural gas can be United States - links to companies listed A-Z with U.S. map imported/exported via pipelines (see map). showing regional breakout detail • 5 LNG (liquefied natural gas) import facilities and 100 LNG peaking facilities. Northeast - CT, DE, MA, MD, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VA, VT, WV Learn more about the natural gas Midwest - IL, IN, MI, MN, OH, WI Southeast - AL, FL, GA, KY, MS, NC, SC, TN pipeline network: Southwest - AR, LA, NM, OK, TX Central - CO, IA, KS, -

Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company, LLC Docket No. CP16-496-000

20170526-4001 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 05/26/2017 Office of Energy Projects May 2017 Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company, LLC Docket No. CP16-496-000 Lone Star Project Environmental Assessment Washington, DC 20426 20170526-4001 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 05/26/2017 FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20426 OFFICE OF ENERGY PROJECTS In Reply Refer To: OEP/DG2E/Gas Branch 1 Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company, L.L.C. Lone Star Project Docket No. CP16-496-000 TO THE PARTY ADDRESSED: The staff of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC or Commission) has prepared an environmental assessment (EA) for the Lone Star Project, proposed by Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company, LLC (Tennessee) in the above-referenced docket. Tennessee requests authorization to construct and operate two new compressor stations in San Patricio and Jackson Counties, Texas. The EA assesses the potential environmental effects of construction and operation of the Lone Star Project in accordance with the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act. The FERC staff concludes that approval of the proposed project, with appropriate mitigating measures, would not constitute a major federal action significantly affecting the quality of the human environment. The proposed Lone Star Project includes the following facilities: • one new bi-directional enclosed Compressor Station 3A in San Patricio County, Texas, consisting of one 10,915 horsepower (hp) International Organization for Standardization (ISO) rated Solar Taurus 70 turbine/compressor unit and associated appurtenances; and • one new bi-directional enclosed Compressor Station 11A in Jackson County, Texas, consisting of one 20,500-hp ISO rated Solar Titan 130 turbine/compressor unit and appurtenances. -

Tennessee Gas Pipeline

Tennessee Gas Pipeline Corporate Headquarters 1001 Louisiana St. Suite 1000 Houston, TX 77002 Phone: 713-369-9000 Website: www.kindermorgan.com/public_awareness Kinder Morgan transports Natural Gas to prevent damage to pipelines and through large diameter transmission protect the public. The leading cause EMERGENCY CONTACT: pipelines in your response area. We are of pipeline accidents is third-party 1-800-231-2800 committed to public safety, protection of damage caused by various types of PRODUCTS/DOT GUIDEBOOK ID#/GUIDE#: the environment, and operation of our digging and excavation activities. Natural Gas 1971 115 facilities in compliance with all applicable • Emergency preparedness and rules and regulations. The majority of planning measures are in place at TENNESSEE our pipelines fall under the regulatory Kinder Morgan in the event that COUNTIES OF OPERATION: oversight of the U.S. Department of a pipeline incident occurs. The Transportation Pipeline and Hazardous company also works closely with local Lobelville District Middleton District Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA). emergency response organizations to Chester Hardeman The company is proud of its safety educate them regarding our pipelines Decatur Hardin record and follows many regulations and and how to respond in the unlikely Dickson McNairy procedures to monitor and ensure the event of an emergency. Henderson integrity of its pipelines. Hickman Portland District • Pipeline operating conditions are CONTACTS Humphreys Cheatham monitored 24 hours a day, 7 days a Lewis Davidson week by personnel in control centers GEORGE WEIR Perry Robertson using a Supervisory Control and Middleton Operations Manager Wayne Sumner Data Acquisition (SCADA) computer (Middleton and Lobelville Districts) ______________________________ system. -

Federal Register/Vol. 65, No. 76/Wednesday, April 19, 2000

20902 Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 76 / Wednesday, April 19, 2000 / Rules and Regulations frequent and routine amendments are Decatur, AL, Decatur/Pryor Field Regional, ACTION: Final rule; order extending time necessary to keep them operationally VOR or GPS RWY 18, Amdt 12, for compliance filings. current. It, thereforeÐ(1) Is not a CANCELLED ``significant regulatory action'' under Decatur, AL, Decatur/Pryor Field Regional, SUMMARY: The Federal Energy VOR RWY 18, Amdt 12 Regulatory Commission is extending the Executive Order 12866; (2) is not a Colusa, CA, Colusa County, VOR or GPS±A, ``significant rule'' under DOT time for pipelines to make filings to Amdt 4B, CANCELLED comply with Order No. 637 relating to Regulatory Policies and Procedures (44 Colusa, CA, Colusa County, VOR±A, Amdt FR 11034; February 26, 1979); and (3) regulation of short-term natural gas 4B transportation services and regulation of does not warrant preparation of a Logansport, IN, Logansport Muni, VOR/DME regulatory evaluation as the anticipated RNAV or GPS RWY 27, Amdt 3, interstate natural gas transportation impact is so minimal. For the same CANCELLED services which was published in the Federal Register of February 25, 2000. reason, the FAA certifies that this Logansport, IN, Logansport Muni, VOR/DME amendment will not have a significant RNAV RWY 27, Amdt 3 DATES: Pipeline compliance filings will Somerset, KY, Somerset-Pulaski CountyÐJ.T. be due on June 15, 2000, July 17, 2000, economic impact on a substantial Wilson Field, NDB or GPS RWY 4, Amdt number of small entities under the and August 15, 2000, according to the 6, CANCELLED schedule set out in SUPPLEMENTARY criteria of the Regulatory Flexibility Act. -

Expanding Gas Supply in the State

OLR RESEARCH REPORT September 17, 2012 2012-R-0407 EXPANDING GAS SUPPLY IN THE STATE By: Kevin E. McCarthy, Principal Analyst Lee R. Hansen, Legislative Analyst II You asked whether there are proposals to expand the gas pipeline system serving the state to provide greater access to the gas being produced in the Marcellus Shale formation in Appalachia. You also asked for options to encourage increased gas supply to the state. SUMMARY Connecticut is currently served by three interstate pipeline systems, Algonquin, Iroquois, and Tennessee. The company that owns the Algonquin pipeline has proposed expanding its existing pipeline’s capacity to facilitate the transmission of gas from the Marcellus Shale formation. Still in its developmental stage, the project is not expected to be in-service until November 2016. The Williams Pipeline Company and Cabot Oil and Gas, an independent natural gas producer, are working to develop a new pipeline to connect Marcellus Shale gas supplies in northern Pennsylvania with major northeastern markets, including Connecticut. While still in the permitting stage, it could be in use by March 2015. Because any interstate pipelines that would be supplying gas from the Marcellus Shale are regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the state’s ability to encourage their expansion through regulatory changes is limited. However, the state could explore ways to make the environment for pipeline expansion more attractive to Sandra Norman-Eady, Director Room 5300 Phone (860) 240-8400 Legislative Office Building FAX (860) 240-8881 Connecticut General Assembly Hartford, CT 06106-1591 http://www.cga.ct.gov/olr Office of Legislative Research [email protected] developers through steps like streamlining permitting processes and encouraging the growth of natural gas demand through financial incentives, such as tax credits, rebates, and lower Contribution in Aid of Construction charges on consumers. -

Southwest Louisiana Supply Project

20160928-4004 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 09/28/2016 Office of Energy Projects September 2016 Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company, L.L.C. Docket No. CP16-12-000 Southwest Louisiana Supply Project Environmental Assessment Washington, DC 20426 20160928-4004 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 09/28/2016 20160928-4004 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 09/28/2016 FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION WA SHINGTON, DC 20246 OFFICE OF ENERGY PROJECTS In Reply, Refer To: OEP/DG2E/Gas 3 Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company, L.L.C. Southwest Louisiana Supply Project Docket No. CP16-12-000 TO THE PARTY ADDRESSED: The staff of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC or Commission) has prepared this environmental assessment (EA) for the Southwest Louisiana Supply Project (Project) proposed by Tennessee Gas Pipeline Company, L.L.C. (Tennessee) in the above-referenced docket. Tennessee requests authorization to construct, operate, and maintain certain interstate natural gas transmission facilities located in the state of Louisiana to provide 295,000 dekatherms per day of natural gas and firm transportation services on Tennessee’s 800 Line system. The purpose of the Project is to meet contractual obligations with Mitsubishi Corporation and MMGS, Inc. The EA assesses the potential environmental effects of the construction and operation of this Project in accordance with the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act. The FERC staff concludes that approval of the proposed Project, with appropriate mitigating measures, would not constitute a major federal action significantly affecting the quality of the human environment. Tennessee proposes to construct a 2.4-mile-long, 30-inch-diameter pipeline lateral in Madison Parish, Louisiana; a 1.4-mile-long, 30-inch-diameter pipeline lateral in Richland and Franklin Parishes, Louisiana; five meter stations; one new compressor station in Franklin Parish, Louisiana; and replace a gas turbine engine at an existing compressor station in Rapides Parish, Louisiana. -

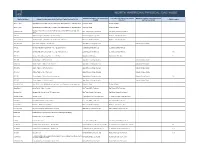

Physical Natural Gas Hub List

Gas Daily Index Reference for NG Firm Phys, Inside FERC Index Reference for NG Firm Natural Gas Intelligence Index Reference for Physical Hub Name Delivery Point Description for NG Firm Phys, FP & NG Firm Phys BS, LD1 ICE NGX Clearable? ID, GDD Phys, ID, IF NG Firm Phys, ID, NGI AB Pool (inter) Agua Blanca Pool (interstate gas only, contact White Water Midstream for applicable rates) Southwest, Waha Southwest, Waha AB Pool (intra) Agua Blanca Pool (intrastate gas only, contact White Water Midstream for applicable rates) Southwest, Waha Southwest, Waha Agua Dulce Hub (sellers' choice, intra-state gas only, contact NET Mexico for applicable Agua Dulce Hub East Texas, Houston Ship Channel East Texas, Houston Ship Channel rates) AGT-CG Algonquin Citygates (Excluding J-Lateral deliveries) Northeast, Algonquin, city-gates Northeast, Algonquin, city-gates AGT-CG (non-G) Algonquin Citygates (Excluding J-Lateral and G-Lateral deliveries) Northeast, Algonquin, city-gates Northeast, Algonquin, city-gates ANR-Joliet Hub ANR Pipeline Company - Joliet Hub CDP Upper Midwest, Chicago city-gates Midwest, Chicago Citygate ANR-SE American Natural Resources Pipeline Co. - SE Gathering Pool Louisiana/Southeast, ANR, La. Louisiana/Southeast, ANR, La. ANR-SE-T American Natural Resources Pipeline Co. - SE Transmission Pool Louisiana/Southeast, ANR, La. Louisiana/Southeast, ANR, La. Yes ANR-SW American Natural Resources Pipeline Co. - SW Pool Midcontinent, ANR, Okla. Midcontinent, ANR, Okla. Yes APC-ANR Alliance Pipeline - ANR Interconnect Upper Midwest, Chicago