Triangle, by David Von Drehle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Should Socialism Prevail

ShouldSocialism Prevail , A DEBATE BETWEEN AFFIRMATIVE NEGATIVE ProfessorScott Nearing Rev. Dr. John L. Relford Mr. Morris Hillquit Prof. FrederickM. Davenport PUBLISHED BY Rand School of Social Science AND New York Call Rudy SocialismBy Correspondence You can get a thorough knowledge of Socialism and its application to Social Problems if you will study OUI courses by mail. Sent weekly to you, these lessons form a systematic course of study at a nominal fee: Form a class of students of any size and we will tell you how to conduct it. If youcannot form a class, take it by yourself. Three Courses are now available: Elements of Socialism-twelve lessons. Social History and Economics-twenty-two lessons, Social Problems and Socialist Policy-twelve lessons. Send for bulletin with complete description to Rand School of Social Science 140 East 19th Street New York City ShouldSocialism Prevail? A DEBATE HELD OCTOBER 21, 1915 BROOKLYN. NEW YORK . Under the Auspices of THE BROOKLYN INSfITUTE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES, SUBJECT:- Resolved,,thirt Socialism ,ought to prevail in the United States. AFFIRMATIVE NEGATIVE Professor Scott Nearing Rev. Dr. John L. Belford Mr. Morris Hillquit Professor Frederick M. Davenport J. Herbert Lowe, Chairman Edited by William M. Feigenbaum Published by The Rand School of Social Science. New York, 1916 ,,\,: . _ *-?-:, _.. s-1’ -’ Kand School of Social Science Xc-x York City Introductory Note I ., , On the 21st of October, 1915, tbere \?ras held undeF.‘t& aus- pices of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts ,ana Sciences a &bate on the subject: “Resolved: that Socialism ought to prevail in the United States.” The Institute had under way the inauguration of a Public Fbrum for the discussion of important matters of pub- lic interest. -

The Triumph and Anguish of the Russian Revolution: Bessie Beatty's

The Triumph and Anguish of the Russian Revolution: Bessie Beatty’s Forgotten Chronicle Lyubov Ginzburg … only time will be able to attribute both the political and the social revolution their true values. Bessie Beatty, the Bulletin, 25 September 1917 The centennial of the Russian Revolution celebrated two and a half years ago has been marked by a pronounced revival of interest in its origins and impact upon modern history all over the globe. The occasion presented an opportunity to revisit the unprecedented social and political upheaval that convulsed the country in 1917, defined the world order for much of the twentieth century, and continues to reverberate in Russian national and international politics to this day. Along with countless newly revealed primary sources which have gradually found their way into the public domain, this event has been encrusted with novel meanings spawned within a growing number of discourses previously excluded from his- torical scrutiny. An example of such a disparity would be an unfortunate slight to gendered narratives in the understanding and interpretation of one of the most controversial social experiments in human history. In spite of the fact that, as with their male counterparts, foreign female correspondents became chroniclers, witnesses, and, in some instances, participants in the thrilling social drama, there have been few references to their representation of the Revolution(s) in its histori- ography.1 Meanwhile, compelled to understanding Russia, while informing com- 1 Although disproportionally less than their men-authored counterparts, women’s narratives have previously sparked some occasional interest among historians and scholars of journalism and women studies. -

John Ahouse-Upton Sinclair Collection, 1895-2014

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cn764d No online items INVENTORY OF THE JOHN AHOUSE-UPTON SINCLAIR COLLECTION, 1895-2014, Finding aid prepared by Greg Williams California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives & Special Collections University Library, Room 5039 1000 E. Victoria Street Carson, California 90747 Phone: (310) 243-3895 URL: http://www.csudh.edu/archives/csudh/index.html ©2014 INVENTORY OF THE JOHN "Consult repository." 1 AHOUSE-UPTON SINCLAIR COLLECTION, 1895-2014, Descriptive Summary Title: John Ahouse-Upton Sinclair Collection Dates: 1895-2014 Collection Number: "Consult repository." Collector: Ahouse, John B. Extent: 12 linear feet, 400 books Repository: California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives and Special Collections Archives & Special Collection University Library, Room 5039 1000 E. Victoria Street Carson, California 90747 Phone: (310) 243-3013 URL: http://www.csudh.edu/archives/csudh/index.html Abstract: This collection consists of 400 books, 12 linear feet of archival items and resource material about Upton Sinclair collected by bibliographer John Ahouse, author of Upton Sinclair, A Descriptive Annotated Bibliography . Included are Upton Sinclair books, pamphlets, newspaper articles, publications, circular letters, manuscripts, and a few personal letters. Also included are a wide variety of subject files, scholarly or popular articles about Sinclair, videos, recordings, and manuscripts for Sinclair biographies. Included are Upton Sinclair’s A Monthly Magazine, EPIC Newspapers and the Upton Sinclair Quarterly Newsletters. Language: Collection material is primarily in English Access There are no access restrictions on this collection. Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Director of Archives and Special Collections. -

((Underground Radicalism"

000954 / ((UNDERGROUND RADICALISM" An Open Letter to EUGENE V. DEBS and to, A(l Honest Workers Wt'tht'n the Socialist Party By l JOHN PEPPER PRICE TEN CENTS PUBLISHED BY - WORKERS PARTY of AMERICA 799 BROADWAY NEW Y ORK CITY ~UldiUl vl IRiD t... ATLANTiC UNlVtK:->lll LIUl\E 441 - tA r CAPITALISM CHAL ENGED AT COURT The trial- of the Communists at St. Joseph, Michigan,has centered the attention of both capitalists and workers of America upon the Communist movement and its repre sentative party, the Workers Party. The testimony of the chief witnesses in the case, Wm. Z. Foster and C. E. Ruthenberg is given verbatim in a splen did pamphlet now being prepared. This court ~ steno graphic report makes a communist agitational pamphlet of great value. It contains a history of the Communist move ment from Marx to the present day. It contains a keen analysis of the movement in this country. It answers the question of revolution by "force and violence." It defends the principle of open propaganda of Communism in the United States. It defends the right of the workers to establish - a Soviet State in the United States. It defends the principle of a Diotatorship of the Worlters to displace the Dictatorship of the Capitalists. Order and seli at workers' meetings. Nominal price. Lot orders at reduced rates. THE WORKERS PARTY 799 BROADWAY NEW YORK CITY E U A CA IS " An Open Letter to EUGENE V . DEBS and to All Honest Workers Within the 'Socialist Party By JOHN PEPPER PRICE TEN CENTS PUBLISHED BY WORKERS PARTY of AMERICA 799 BROADWAY NEW YORK CITY CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I.-The Working Class In Dangler The New Offensive of the Capitalists. -

A Rip in the Social Fabric: Revolution, Industrial Workers of the World, and the Paterson Silk Strike of 1913 in American Literature, 1908-1927

i A RIP IN THE SOCIAL FABRIC: REVOLUTION, INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD, AND THE PATERSON SILK STRIKE OF 1913 IN AMERICAN LITERATURE, 1908-1927 ___________________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ___________________________________________________________________________ by Nicholas L. Peterson August, 2011 Examining Committee Members: Daniel T. O’Hara, Advisory Chair, English Philip R. Yannella, English Susan Wells, English David Waldstreicher, History ii ABSTRACT In 1913, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) led a strike of silk workers in Paterson, New Jersey. Several New York intellectuals took advantage of Paterson’s proximity to New York to witness and participate in the strike, eventually organizing the Paterson Pageant as a fundraiser to support the strikers. Directed by John Reed, the strikers told their own story in the dramatic form of the Pageant. The IWW and the Paterson Silk Strike inspired several writers to relate their experience of the strike and their participation in the Pageant in fictional works. Since labor and working-class experience is rarely a literary subject, the assertiveness of workers during a strike is portrayed as a catastrophic event that is difficult for middle-class writers to describe. The IWW’s goal was a revolutionary restructuring of society into a worker-run co- operative and the strike was its chief weapon in achieving this end. Inspired by such a drastic challenge to the social order, writers use traditional social organizations—religion, nationality, and family—to structure their characters’ or narrators’ experience of the strike; but the strike also forces characters and narrators to re-examine these traditional institutions in regard to the class struggle. -

Pre-Election Colic

VOL. 1 1 , NO. 9 0 . NEW YOR K, WED NESD AY, SEPT EM B ER 2 8 , 1 9 1 0 . ONE CENT . EDITORIAL THE “CALL’S” PRE-ELECTION COLIC. By DANIEL DE LEON HE long and nervous editorial in which the New York Call of the 6th of the current month, following the lead of the New Yorker Volkszeitung, long and TT nervously urges its Socialist party to hasten to adopt the planks upon which Roosevelt had just launched himself on the choppy political sea of the land, lest the S.P. go down in wreck and ruin, is a prime specimen of the colic that attends political and economic indigestion. The Roosevelt planks are summarized in the plank that denounces the judiciary, a branch of the capitalist government that the colicky Call pronounces “the most formidable political weapon of the capitalist class against the working class.” For one thing, most of the outrageously class decisions rendered by the judiciary have been rendered by the Federal judiciary, that is, by an appointative body, appointed by the Executive with the consent of the upper branch of the Legislature. In other words, this judiciary engine of despotism is not reachable, curbable or curable without first reaching the Executive and the Legislature. For another thing, the whole judiciary—State and Federal, elective or appointative—is in the hollow of the hand of the respective Legislatures. The judiciary can not be corrupt, let alone practise tyranny upon the proletariat, without the knowledge, the consent, the approval and the support of the Legislature. -

Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press Adult Education Research Conference 2002 Conference Proceedings (Raleigh, NC) Creating a Place for Learning: Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement Marilyn McKinley Parrish Penn State University, USA Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/aerc Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Administration Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Parrish, Marilyn McKinley (2002). "Creating a Place for Learning: Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement," Adult Education Research Conference. https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2002/papers/52 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Adult Education Research Conference by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Creating a Place for Learning: Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement Marilyn McKinley Parrish Penn State Harrisburg, USA Abstract: This is an examination of Dorothy Day’s approach to social activism, the development of the Catholic Worker movement, and the learning that took place within it. The intent is to contribute to a more complete history of the education of adults in twentieth century American society. Introduction Adult education history has often been presented as a chronicle of the efforts of the dominant culture (largely white, male, and middle class) and focused on the institutionalization and professionalization of the field (Rose, 1989; Thompson, 1997; Welton, 1993). Learning within certain groups and outside formal institutions has been largely ignored (Schied, 1995). -

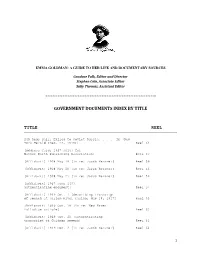

Government Documents Index by Title

EMMA GOLDMAN: A GUIDE TO HER LIFE AND DOCUMENTARY SOURCES Candace Falk, Editor and Director Stephen Cole, Associate Editor Sally Thomas, Assistant Editor GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS INDEX BY TITLE TITLE REEL 249 Reds Sail, Exiled to Soviet Russia. In [New York Herald (Dec. 22, 1919)] Reel 64 [Address Card, 1917 July? for Mother Earth Publishing Association] Reel 57 [Affidavit] 1908 May 18 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1908 May 20 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1908 May 21 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1917 June 1[0? authenticating document] Reel 57 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 1 [describing transcript of speech at Harlem River Casino, May 18, 1917] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 18 [in re: New Haven Palladium article] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 20 [authenticating transcript of Goldman speech] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Dec. 2 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 64 1 [Affidavit] 1920 Feb. 5 [in re: Abraham Schneider] Reel 65 [Affidavit] 1923 March 23 [giving Emma Goldman's birth date] Reel 65 [Affidavit] 1933 Dec. 26 [in support of motion for readmission to United States] Reel 66 [Affidavit? 1917? July? regarding California indictment of Alexander Berkman (excerpt?)] Reel 57 Affirms Sentence on Emma Goldman. In [New York Times (Jan. 15, 1918)] Reel 60 Against Draft Obstructors. In [Baltimore Sun (Jan. 15, 1918)] Reel 60 [Agent Report] In re: A.P. Olson (or Olsson)-- Anarchist and Radical, New York, 1918 Aug. 30 Reel 61 [Agent Report] In re: Abraham Schneider--I.W.W., St. Louis, Mo. [19]19 Oct. 14 Reel 63 [Agent Report In re:] Abraham Schneider, St. -

The Class Appeal of Marcus Garvey's Propaganda and His Relationship with the Black American Left Through August 1920

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2015 The Class Appeal of Marcus Garvey's Propaganda and His Relationship with the Black American Left Through August 1920 Geoffrey Cravero University of Central Florida Part of the Public History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Cravero, Geoffrey, "The Class Appeal of Marcus Garvey's Propaganda and His Relationship with the Black American Left Through August 1920" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 65. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/65 THE CLASS APPEAL OF MARCUS GARVEY’S PROPAGANDA AND HIS RELATIONSHIP WITH THE BLACK AMERICAN LEFT THROUGH AUGUST 1920 by GEOFFREY V. CRAVERO B.A. University of Central Florida, 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2015 Major Professor: Connie Lester © 2015 Geoffrey V. Cravero ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the class appeal of Marcus Garvey’s propaganda and his relationship with the black American left through the end of his movement’s formative years to reveal aspects of his political thought that are not entirely represented in the historiography. -

Russia — the World's Greatest Labor Case

Minor: Russia — The World’s Greatest Labor Case [Sept. 14, 1919] 1 Russia — The World’s Greatest Labor Case: A Speech in San Francisco. by Robert Minor Published in the New York Call Magazine, September 14, 1919, pp. 1, 4-5. Robert Minor, cartoonist, formerly associated with than in those 30 years. Among other things, we have the New York Call, has recently returned to the United had the labor movement pure and simple, in the most States from Soviet Russia. We publish below the second reactionary land, actually take charge of the affairs of speech that Minor has delivered since he returned. Minor the biggest white race on earth, and it has triumphantly tells some things about Russia which the world may not managed those affairs for 2 years. have heard before. He argues for the withdrawal of Ameri- I lived for the better part of one year in the city can troops from Russia and a complete Recognition of the of Moscow. There I met a common Russian soldier, Soviet government. Minor is in San Francisco. and I was surprised to see on his uniform a little but- —Sunday Editor [David Karsner]. ton labeled “The San Francisco Martyrs.” You know the world has come to that • • • • • point where there are no more movements, except The last time that I stood on international movements. this platform was 3 years ago, when Some people do not know, a little group of labor unionists and cannot understand, that a few cranky journalists like myself the world has made that undertook to tell San Francisco citi- tremendous leap of the zens, and especially the organized la- past 3 years and that the bor portion of San Francisco, that world is going to retain the there was a labor case about to start. -

Inside Greenwich Village: a New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918 Gerald W

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst University of Massachusetts rP ess Books University of Massachusetts rP ess 2001 Inside Greenwich Village: A New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918 Gerald W. McFarland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/umpress_books Part of the History Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation McFarland, Gerald W., "Inside Greenwich Village: A New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918" (2001). University of Massachusetts Press Books. 3. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/umpress_books/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Massachusetts rP ess at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Massachusetts rP ess Books by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Inside Greenwich Village This page intentionally left blank Inside Greenwich Village A NEW YORK CITY NEIGHBORHOOD, 1898–1918 Gerald W. McFarland University of Massachusetts Press amherst Copyright ᭧ 2001 by University of Massachusetts Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America LC 00-054393 ISBN 1–55849-299–2 Designed by Jack Harrison Set in Janson Text with Mistral display by Graphic Composition, Inc. Printed and bound by Sheridan Books, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McFarland, Gerald W., 1938– Inside Greenwich Village : a New York City neighborhood, 1898–1918 / Gerald W. McFarland. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 1–55849-299–2 (alk. paper) 1. Greenwich Village (New York, N.Y.)—History—20th century. 2. Greenwich Village (New York, N.Y.)—Social conditions—20th century. -

The Brass Check a Study of American Journalism by Upton Sinclair

Digitized for Project Gutenberg by Jane Rutledge ([email protected]) on behalf of Friends of Libraries USA (http://www.folusa.org) and Betsy Connor Bowen (http://journal.maine.com/lore/loonalone/) on behalf of TeleRead (http://www.teleread.org). This is a preview version—not an official Gutenberg one. Questions? Contact David Rothman at [email protected]. July 16, 2003 The Brass Check A Study of American Journalism By Upton Sinclair Who owns the press, and why? When you read your daily paper, are you reading facts, or propaganda? And whose propaganda? Who furnishes the raw material for your thoughts about life? Is it honest material? No man can ask more important questions than those; and here for the first time the questions are answered in a book. ===========End of Cover Copy=========== Published by the Author Pasadena, California ====================== PART 1: THE EVIDENCE --- I. The Story of the Brass Check Sinclair, The Brass Check, p.2 of 412 II. The Story of a Poet III. Open Sesame! IV. The Real Fight V. The Condemned Meat Industry VI. An Adventure with Roosevelt VII. Jackals and a Carcase VIII. The Last Act IX. Aiming at the Public's Heart X. A Voice from Russia XI. A Venture in Co-operation XII. The Village Horse-Doctor XIII. In High Society XIV. The Great Panic XV. Shredded Wheat Biscuit XVI. An Interview on Marriage XVII. "Gaming" on the Sabbath XVIII. An Essential Monogamist XIX. In the Lion's Den XX. The Story of a Lynching XXI. Journalism and Burglary XXII. A Millionaire and an Author XXIII.