Computing Abilities in Antiquity: the Royal Judahite Storage Jars As a Case-Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pg 449-521 Sites

449 5.3 SOUTHERN KINGDOM OF JUDAH 5.3.1 Hill Country of Judah BETH-ZUR Beth-Zur is identified as modern Khirbet Tubeiqah. It was an important city in Judah located on the old Jerusalem-Hebron road, about 20 miles south of Jerusalem and 4.5 miles north of Hebron. It controlled not only the southern approach to Jerusalem, but important routes to the Shephelah to the west. Beth-Zur is mentioned in several scriptures. It was on the town list for the territory of Judah (Joshua 15:58 and 1 Chronicles 2:45.), fortified by Rehoboam (2 Chron. 11:7) and later was the administrative center of a half-district in the day of Nehemiah (3:16). The excavations of Beth-Zur took place in 1931 and 1957, under the direction of O. R. Sellers. Almost 8,000 square meters of the summit of the Tell was cleared to bedrock in 1931. Fields I, II, and III were assigned to the plan of the excavation. Continuous excavation resulted in exposing the Iron Age I and II levels, Middle Bronze, and Early Bronze. Further work was done on Fields I and III on the northeast side of the city and Field II on the southeast. Both campaigns supplemented each other and supported the results of the first expedition. Remains of the Iron Age I settlement are concentrated for the most part on the north side of the hill. Numerous walls and piers of houses were found for this period during the 1931 dig. In 1957, it was discovered that during Iron 450 Age I the city area had been reduced in size on the north and a new city wall built. -

Hélade, V. 5, N. 2

THE KING IS DEAD. LONG LIVE THE KING! THE SEMIOTICS OF POWER TRANSITION IN THE LMLK STAMPED AND THE CON- 247 CENTRIC-CIRCLES INCISED JUDAHITE JAR HANDLES Jorge Luiz Fabbro da Silva1 Abstract: The paper briefly discusses – on the basis of the historical and -ar chaeological data, and from a semiotic theoretical perspective – the possible context that produced the Judahite jar handles marked with lmlk stamps and/ or concentric circles incisions. It argues that is not conceivable that the Assyri- an king Sennacherib had subjugated Hezekiah, the king of Judah, reduced his dominion in favor of the Philistines, and increased his tax burden, without having also altered the very symbol system that represented the sovereignty of the Judahite king. It proposes that the concentric circles (1) were an Assyrian imposition over Judah, (2) should be understood in the light of the Philistine iconography, and (3) had the function of distinguishing jars intended to collect taxes for the king of Judah from those intended to collect tributes for the king of Assyria or for Assyrian interests. Dossiê Keywords: lmlk jars, winged symbols, concentric circles symbols, Kingdom of Judah, Senacherib’s campaign, Philistines Resumo: O artigo discute brevemente – com base nos dados históricos e ar- queológicos, e de uma perspectiva teórica semiótica – o possível contexto que produziu as alças dos jarros judaítas marcadas com selos lmlk e/ou incisões de círculos concêntricos. Argumenta que não é concebível que o rei assírio Se- naqueribe tenha subjugado Ezequias, rei de Judá, reduzido seu domínio em favor dos filisteus e aumentado sua carga tributária, sem também ter alterado o próprio sistema de símbolos que representava a soberania do rei judaíta. -

Archaeology and the Bible

Archaeology and the Bible In recent years archaeological discoveries in the Near East, particularly in Palestine, have been related in one way or another to the Bible, often in an effort to prove its historical veracity. But newer field methodologies, regional surveys and creative syntheses have called into question this traditional approach. Archaeology and the Bible examines these new developments and discusses what they imply for biblical studies. The book: • traces the history of the development of Near Eastern archaeology, including the rise and fall of the so-called “biblical archaeology” movement • describes how field archaeology is actually done so that the reader can visualize how archaeological discoveries are made, recorded and studied • recounts the broader prehistorical/archaeological horizon out of which the Bible was born • elucidates how recent archaeological discoveries and theorizing pose serious challenges to the traditional interpretations of such biblical stories as the “Exodus” and the “Conquest” • explores the implications of new developments in the field for understanding Israelite religion. Archaeology and the Bible presents a concise yet comprehensive and accessible introduction to biblical archaeology which will be invaluable to students. John C. H. Laughlin is Professor of Religion and Chairman of the Department of Religion at Averett College. He has excavated at Tel Dan and served as Field Supervisor at the Capernaum excavations. Since 1989, he has been a Field Supervisor at Banias. He has published and lectured widely on the subjects of Near Eastern archaeology and the Bible. Approaching the Ancient World Series editor: Richard Stoneman The sources for the study of the Greek and Roman world are diffuse, diverse, and often complex, and special training is needed in order to use them to the best advantage in constructing a historical picture. -

Joshua Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY ON JOSHUA Abramowitz, Chaim (1984) "THE THREE DAY SYNDROME. Dor Le Dor; 1985 13(2):111–116. Interprets the actions of Joshua prior to capturing Jericho: the sending of the spies and his strategy. The repeated phrase "three days" has been understood to be a general, not specific quantity, thus misleading the interpreters. However, the sequence of events can be accurately reconstructed. From Adar 7 to Nissan 7, there was a mourning period for Moses. On Nisan 8 the spy mission began. There are several sets of three days that can be accounted for between Nisan 8 and 14. Abramson, Sharaga (1979) "CHAPTERS CONCERNING RABBI JUDAH HAYYUJ AND RABBI JONAH IBN GANAH, 1) FROM THE "KITAB AL-NATAF" ON THE BOOK OF JUDGES. Leshonenu 43(4):260–270. The beginning of a commentary on Judges, which was attached to Hayyuj's commentary on Joshua, is presented here. Stylistic considerations indicate that its author was the Spaniard Rabbi Isaac the son of Samuel. The second part of the article deals with ibn Ganah's understanding of the root sbb, absent from published manuscripts of his Kitab Al-Mustalhaq. This is culled from other medieval authors. (Hebrew) Abramson, Shraga (1977) "FROM THE KITAB ALNATAF OF RABBI JUDAH HAYYUJ ON 2 SAMUEL. Leshonenu; 1978 42(3/4):203–236. The Hebrew grammarian Judah ibn Hayyuj is reported by later grammarians to have written four books on biblical grammar, one of which is the Kitab al-Nataf. This book is ordered on the sequence of verses and explains difficult passages. The material from existing manuscripts is presented together with reactions of later grammarians. -

Yahweh's Winged Form in the Psalms ORBIS BIBLICUS ET ORIENTALIS

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2010 Yahweh’s Winged Form in the Psalms: Exploring Congruent Iconography and Texts LeMon, Joel M Abstract: The striking image of the winged Yahweh occurs in six psalms (e. g., Ps 17:8 “Hide me in the shadow of your wings”). Scholars have disagreed on the background, meaning, and significance of the image arguing that it: (1) likens the Israelite deity to a bird; (2) alludes to the winged sun disk; (3) draws from general Egyptian symbolism for protection; (4) evokes images of winged goddesses; or (5) refers to winged cherubim in the temple and/or on the ark of the covenant. These divergent proposals signal a need for clearer methods of interpreting biblical imagery in light of visual-artistic material from the ancient Near East. This volume refines iconographic methodologies by treating the image of the winged Yahweh as one among a constellation of literary images in each psalm. Since the portrayals of Yahweh in each psalm have distinct contours, one finds several congruencies in Syro-Palenstinian iconographic material. The congruent iconographic motifs for Yahweh’s winged form include (1) the winged sun disk (in multiple form and variations), (2) the Horus falcon, (3) winged suckling goddesses, and (4) winged deities in combat. No single image stands behind the portrayals of Yahweh. In fact, even within a single psalm, more than one iconographic trope can provide congruency with the literary imagery and inform the interpretation of the text. Thus, the winged Yahweh in the Psalms provides an example of a ‘multistable’ literary image, one which simultaneously evokes multiple iconographical motifs. -

E-STRATA No. 2 (2020)

E-STRATA No. 2 (2020) Nahal Hever, Judean Desert, Eitan Klein. Eitan Desert, Judean Hever, Nahal Photo: survey of the Northern Cliff of NorthernCliff the of survey Photo: Newsletter of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society www.aias.org.uk E-STRATA No. 2 (2020) IN THIS ISSUE In the News 2 In Conversation with Eitan Klein 18 Nick Slope’s Adventures from the Holy Land 26 Tailpiece 31 Dear Friends, As autumn peers towards winter, we are delighted to bring you E-Strata 2 for cosy days and nights indoors. Despite the New Old that continues to challenge the world, including excavations in Israel, archaeologists, historians and museum curators are still weaving a rich tapestry to re-write and re-address what we know about the ancient Near East. So we’re able to share 16 pages of news. And the floodgates continue to give. As we go to press, an 8th or 7th century BCE ‘palace’ has turned up in the East Talpiot district of Jerusalem with perfectly preserved stone col- umn capitals. The first cluster of deep-sea shipwrecks off Israel has beeen discovered in the Leviathan gas field, dating back to the Late Bronze Age. A hoard of 425 golden Abbasid coins from the 9th century are gleaming in an undisclosed location in central Israel. May the discoveries continue on land, sea and library shelves. E-Strata is fortunate to have caught up with Dr Eitan Klein, a committee member of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society. Eitan is the Deputy Director of the Antiquities Theft Prevention Unit at the Israel Antiquities Authority and lifts the lid on the struggle to con- tain site looting and talks about his latest work with the Judean Desert Caves Project. -

Judaean Stamps*

17 Judaean Stamps* [1969] I the stratigraphy of Ramat RaJ:iel, 2 cEn Gedi, 3 and La chish. 4 It is more difficult to fix the precise fioruit of the The series of official or quasi-official stamps used on lam-melek series with its several types. The evidence that jars in Judah begins in the late eighth century BCE with all were made from a handful of master stamps suggests a the so-called lam-melek impressions. 1 The clarification short span of time for their usage. 5 There is no clear evi of the date of Stratum III at Lachish appears to certify dence either from stratigraphic context or from palaeog that both the royal stamps engraved with the scarab, and raphy6 that any of the stamps need be dated later that those engraved with the winged sun disk, belong wholly c. 700 BCE. The scripts of the two major groups 7 differ or in large measure to late in the reign of Hezekiah (727- BCE). 698 That these stamps did not continue in use until 2. Ramat Ra/:tel: 1959 and 1960 (above, n. 1): 59--60. The royal the end of the kingdom is established by the evidence of stamped handles were found only under the floor of the courtyard and beneath the floors of the buildings. If we follow the excavator in dating the citadel to the time of Jehoiakim, we must then conclude that Ramat 'This paper has been revised to remove error and to conform to Ral;iel provides negative evidence for the discontinuance of the stamps my present views. -

To Preview the Technical Highlights & Index/Concordance

vol. 1 by G.M. Grena Revision #: 1730 # of pages: 425 # of words: 206,355 # of characters: 1,004,942 Date Submitted to Printer: 2004-04-01 Printed & Bound by: InstantPublisher.com Published by: 4000 Years of Writing History 409 N Pacific Coast Hwy 404 Redondo Beach CA 90277 USA [email protected] (310) 200-4856 Copy #: _____________ of _____________ This document, as a whole or in parts, is public domain that may be copied & distributed without restrictions; the author, G.M. Grena, retains only the right to make changes to this document for future editions without giving notice to other publishers. If you think you can do a better job of publishing this LMLK research, go for it! ISBN 0-9748786-0-X Library of Congress Control Number: 2004091485 LmLk --A Mystery Belonging to the King vol. 1 Layer 0 Scholars Start Here "Learn to say 'I do not know.'" --Hebrew apothegm Wonderful things within to whet your appetite: On LMLK seals, all HBRN inscriptions were scriptio defectiva; all SUKE inscriptions were plene; & of the 6 LMLK seals with Z(Y)F, half were plene & half defectiva. See pages 49-51 for Biblical references. Chapter 5 introduces a new LMLK seal classification system that overcomes the ambiguities in Welten's & introduces 2 types previously ignored by Lemaire's that have since proven to be unique & legitimate by multiple examples (both new & old ones that were previously overlooked). Figure 39 on page 70 shows a 1:1 template of all 21 LMLK seal types for reference when reporting new finds. -

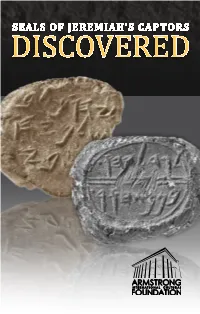

Discovered Discovered

SEALS OF JEREMIAH’S CAPTORS DISCOVERED Dear visitor, Welcome! We are thrilled to be able to share these precious artifacts, and the remarkable history of ancient Israel. Biblical history is a fascinating and important subject. These relics bring to King Solomon, the heartache of Judah’s life the magnificence of ancient Israel under captivity and Jerusalem’s destruction, and the impressive faith and courage of the Prophet Jeremiah. We encourage you to take as much time as you need to let this history—and the lessons it imparts—sink in. We would also like to express our deepest gratitude to Dr. Eilat Mazar for her vital contributions to this exhibit. Were it not for the tireless efforts of Dr. Mazar and her late grandfather, Professor Benjamin Mazar, many of these artifacts, including the bullae, would lay undiscovered in the soils of Jerusalem. We treasure our long history with the Mazar family and consider it a tremendous blessing to have been by her and her grandfather’s side these past 44 years. We stand ready, spade in hand, to support Dr. Mazar as she continues to uncover the secrets of ancient Jerusalem. GERALD FLURRY FOUNDER AND CHAIRMAN ARmstRONG INTERNATIONAL CULTURAL FOUNDATION 2012 EXHIBITION 1 c. 1447 b.c. Israelite exodus 1407 b.c. Israelites enter from Egypt. Promised Land. United Kingdom King David ruled Israel from the city of Hebron for 7½ years (circa 1007 ). Although the Israelites had entered Canaan more than 400 years prior, one city remained unconquered: Jerusalem. Situated right in the b.c. lived there boasted that “the blind and the lame” could defend it. -

The Judean Imlk Stamps: Some Unresolved Issues

The Judean Imlk Stamps: Some Unresolved Issues MICHAEL S. MOORE Allentown, Pennsylvania One of the more complex problems in Syro-Palestinian archaelogy has to do with the discovery, analysis, and interpretation of the Imlk seals of Iron Age Judah. Just around every bend in the twists and turns of the secondary literature on this subject a different opinion is expressed about some aspect of these seals. Why are there four-winged and two-winged impressions? Why is the lettering on many so crude and effaced? Can a paleographical development be traced? What does the imagery represent? Can its development be traced? How many actual seals were responsible for the ca. 1000 jar-handle stamps unearthed so far? What meaneth these four names-Socoh, Hebron, Ziph, and mmst ? What relationship, if any, exists between the Imlk seals and the private seals? Can these seals shed light on a crucial period in biblical history? This last question, of course, is the question with which biblical scholars most want to engage, yet the present controversy encircling the different answers offered cannot be appreciated fully without careful atten tion being paid to the archaeological foundations undergirding them. It seems wisest, moreover, not to attempt here to survey extensively all the questions raised in the previous paragraph, but to focus on a few of the more entangled areas of disagreement. Consequendy, this paper will arbi trarily be limited to a discussion of three areas: (1) paleography, (2) the significance of the four place-names, and (3) the light, if any, which these seals can shed on our attempts to reconstruct the history of Israel in the Iron Age. -

Second Report on the Excavations at Tell Ej- Judeideh

Palestine Exploration Quarterly ISSN: 0031-0328 (Print) 1743-1301 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ypeq20 Second Report on the Excavations at Tell Ej- Judeideh F. J. Bliss To cite this article: F. J. Bliss (1900) Second Report on the Excavations at Tell Ej-Judeideh, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 32:3, 199-222, DOI: 10.1179/peq.1900.32.3.199 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/peq.1900.32.3.199 Published online: 20 Nov 2013. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 9 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ypeq20 Download by: [Monash University Library] Date: 02 July 2016, At: 09:59 Downloaded by [Monash University Library] at 09:59 02 July 2016 199 SECOND REPORT ON THE EXCAVATIONS AT TELL , EJ-JUDEIDEH. By F. J. BLISS, Ph.D. EXCAVATIONS were resumed at this site'on, Monday, March 19th, and the work has been closed to-day (June 1st), when the Tell .shows the saIne lev'el top that it had on the day .operations began. In the meantime some 125,000 cubic feet of earth and :stones have been piled up on the surface, and the extensive T~mains of a ROlnan villa have been exposed .to view. The -covering in of excavations is one of the penalties that. have to be paid when diggings are made on arable, lan~l. FQQ.rdaY!3 have been lost to theex~avations-twoon a~cQunt 9f raiil. -

Hebrew, Moabite, Ammonite, and Edomite Inscriptions1

LITERARY SOURCES FOR THE HISTORY OF PALESTINE AND SYRIA. 11: HEBREW, MOABITE, AMMONITE, AND EDOMITE INSCRIPTIONS1 DENNIS PARDEE The University of Chicago Beside the Hebrew Bible, which has been preserved as a literary and religious document by the Jewish and Christian communities, modern archaeology has placed a series of inscrip- tions in Hebrew and closely related dialects recovered from the soil of Palestine it~elf.~Most of these documents are brief, they usually do not refer specifically to events mentioned in the Bible, and their number has been growing rapidly only in the last forty years or so. Thus they are not generally well known except to specialists in epigraphy, philology, and history. Probably the two best known of these inscriptions are the Mesha Stone, the earliest inscription (ca. 850 B.c.) of considerable length in a dialect close to classical Hebrew, and the Siloam Tunnel in- scription, which contains an account parallel to the biblical version (2 Kgs 20:20; 2 Chr 32:30; cf. Sir 48:17) of the com- pletion of Hezekiah's water tunnel under Jerusalem's east hill. This is the second article of a series, the first of which appeared in AUSS 15 (1977): 189-203. The reader should note that the various installments do not represent a chronological order, hut only a discrete unit of literary material which the writer feels best able to present in published form at a given time. ZI am dealing here only with texts which antedate the bulk of the texts from the Dead Sea caves. The latter will be the object of a future study in this series.